Doppler Renal Assessment, Protocols, and Interpretation

Doppler Renal Assessment, Protocols, and Interpretation

Introduction

Doppler ultrasound (US) is a well-established and useful technique for evaluating the renovascular system and associated pathologic conditions. As with other US examinations, advantages include its noninvasive nature, relatively low-costs, and generally well-tolerated. However, the technique is highly operator-dependent and can be time-consuming. Furthermore, the interpretation of renal Doppler US examinations might be challenging for those with limited experience or those unfamiliar with fundamental concepts and nomenclature.

Nevertheless, due to its benefits, the American College of Radiology (ACR) Appropriateness Criteria guidelines rate renal Doppler US as appropriate or even first-line imaging technique in various clinical scenarios, especially in patients with decreased renal function or renal transplants when contrast administration for computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging examinations might be problematic.[1][2] In this article, we review the vascular anatomy, imaging indications, and technique, along with a short discussion about clinical significance and common pathologies.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

The kidneys are located in the retroperitoneum and receive approximately 20% of the cardiac output.[3] Typically, one renal artery and vein supply each kidney, with the arterial supply originating from the abdominal aorta, just below the level of the superior mesenteric artery, at the level of L1-L2. However, it should be noted that in approximately 30% of individuals, an accessory renal artery is present, and in 10 to 15 % on both sides. The main renal arteries are approximately 4 to 6 cm long with a 5 to 6 mm diameter. The right renal artery, which is longer than the left, arises from the anterolateral aorta and runs in an inferior course posterior to the inferior vena cava (IVC) to reach the right kidney. The left renal artery arises more lateral of the aorta and courses almost horizontally to the left kidney posterior to the left renal vein. During their course, the renal arteries supply small branches to the adrenal gland, proximal ureter, and renal capsule; however, these branches are usually not seen by US/imaging due to their small caliber.

Before entering the renal hilum and parenchyma, the main renal artery divides into five segmental branches, including apical, superior, middle, inferior, and posterior segmental arteries. The segmental arteries supply end arteries to the renal parenchyma and divide further into lobar, interlobar, arcuate, and interlobular arteries. The interlobular arteries supply the afferent glomerular arterioles, which, in turn, feed into the glomeruli.

The renal veins generally lie anterior to the renal arteries at the renal hilum. The left renal vein measures 6 to 10 cm in length and is significantly longer than the right renal vein, which measures 2 to 4 cm. The left renal vein passes between the aorta and the superior mesenteric artery before entering the IVC medially. During its course, the left renal vein receives almost always blood from the left adrenal and gonadal veins and, in the majority of patients, from the lumbar veins. The most common congenital anomaly of the left renal venous system is the circumaortic left renal vein (consisting of anterior and posterior limbs that encircle the abdominal aorta) seen in up to 17 % of the population. The shorter right renal vein empties into the IVC laterally, noting that, when compared to the left, the right gonadal and adrenal veins drain into the right renal vein more infrequently in only 7 % and 31 % of cases, respectively.[3][4][5]

Indications

Doppler US examination of the renal vasculature plays a critical role in the evaluation of native as well as transplanted kidneys.

Indications for Doppler US of native renal arteries include hypertension (particularly when there is strong suspicion for renovascular hypertension), follow-up of patients with the known renovascular disease who are under medical supervision or after the endovascular intervention, evaluation of abdominal/flank bruit, evaluation of a suspected vascular pathology (e.g., aneurysm, pseudoaneurysm, arteriovenous fistula), evaluation of vascular causes of acute renal failure, evaluation of renal blood flow in patients with previously diagnosed abnormalities that may compromise blood flow to the kidneys (e.g., aortic dissection or trauma), evaluation for renal size asymmetry, and evaluation for renal vein thrombosis.[6][7][8]

Indications for Doppler US of transplant renal arteries include screening to determine baseline values of hemodynamic parameters, abnormalities such as tenderness, rising creatinine, oliguria/anuria, hematuria, or ureteral dilatation, evaluation of vascular patency, evaluation for iatrogenic complications post-biopsy, and assessment for lymphoproliferative disease.[6]

Contraindications

There are no absolute contraindications to perform a renal Doppler US examination. However, the study may be of limited diagnostic value in patients with obesity or overlying bowel gas, difficult/aberrant anatomy (e.g., horseshoe kidney, multiple renal arteries, tortuous vessel), cardiac/aortic pulsation, and critically ill patients with difficulty following commands (e.g., extensive respiratory motion).[6] The deep location of both kidneys in the retroperitoneum with relatively small caliber renal arteries further adds to technical challenges which are associated with this study.

Equipment

Ultrasound machines used for Doppler US examinations need to be able to perform Duplex scanning, which refers to the combination of 2D B-mode imaging and pulsed Doppler data acquisition. This usually includes three types of Doppler: color Doppler to obtain flow information (such as direction and magnitude of flow), power Doppler to visualize subtle and slow blood flow (at the expense of directional and quantitative flow information), and spectral Doppler to show blood flow velocity over time as a waveform. Probe selection should be based on body habitus. In general, a lower frequency, the curvilinear transducer, is preferred (typically 3.5 to 5 MHz) in adult patients since both renal arteries and kidneys are in a deep location. However, a 6 to 12 MHz linear transducer might be used to improve flow detection in thin or pediatric patients.

Personnel

Interpreting physicians should have a comprehensive understanding of renal Doppler US. That includes knowledge about study indications and limitations, anatomy and pathophysiology of the examined organ system, and the ability to correlate additional medical information with the sonographic findings. Maintenance of competence and continued medical education should be ensured as is appropriate to his/her practice. In addition, diagnostic medical sonographers should have received pertinent training and complete ongoing continuing education in the US. Adequate certification criteria have to be fulfilled by physicians and sonographers.

Preparation

Before a renal Doppler US, patients should remain NPO for eight hours. This includes tobacco products or chewing gums as this promotes the ingestion of air which subsequently limits the examination due to artifacts. However, for renal transplant examinations, patients do not need to be NPO. If patients need to take necessary medications before their exam, this can be achieved with a small glass of water. Simethicone is a well-known emulsifying agent, and prior research has shown its ability to break down large pockets of gas. Hence, Simethicone can be administered to improve sonographic visualization, especially in patients with obesity; however, the cost-effectiveness of the routine use of Simethicone is questionable, and hence this is currently not standard in daily clinical practice.[9]

Technique or Treatment

The renal vascular evaluation should always start with B-mode grayscale imaging, including long and short axis imaging of both kidneys to determine the size, location, and echotexture. Moreover, it should be evaluated for the presence of any focal renal abnormality, the renal corticomedullary differentiation, and, particularly in transplanted kidneys, for potential perirenal fluid collections.

Color Doppler images to evaluate blood flow should be performed in the proximal, mid, and distal renal arteries bilaterally and at the origin of each renal artery from the aorta. In addition, color-coded evaluation of blood flow can assist in the identification of any duplicate renal artery. When high velocities are encountered, specific attention should be paid to an error called aliasing (showing as the projection of color of reversed flow within central areas of a vessel), which indicates turbulent flow, and therefore possible stenosis or arteriovenous fistula. This can be corrected by increasing the velocity scale to exceed the peak velocity of the sampled vessel.[10]

Using Spectral Doppler, the peak systolic velocity (PSV) should be measured in the abdominal aorta at the level of the renal arteries, as well as in the renal artery origin, middle portion, and hilum (in the main renal artery, normal values are 60-100 cm/s).[3] Regardless of transducer position, an angle correct to 60 degrees or less is mandatory to get accurate information. The PSV in the renal artery and PSV in the aorta can also be used to calculate the renal to the aortic ratio, which should be < 3.5. Spectral recording of blood flow is further performed at the intrarenal level using segmental and interlobar arteries, specifically at the upper pole, central part, and lower pole of the kidney. Other criteria evaluated during the examination of intrarenal arteries include acceleration time (AT) (time of the start of systole to peak systole; <70 msec considered normal) and acceleration index (AI) ( slope of the systolic upstroke; > 3 m/s considered normal).[3] Finally, with Spectral Doppler evaluation, the resistive index (RI) can be determined by dividing the difference between the PSV and end-diastolic velocity by the PSV (normal range is 0.5 to 0.7).

Power Doppler has certain benefits due to its greater sensitivity to flow and reduced angle dependence. This is especially helpful when assessing global renal perfusion and the parenchymal microvasculature to evaluate for cortical perfusion defects.[11]

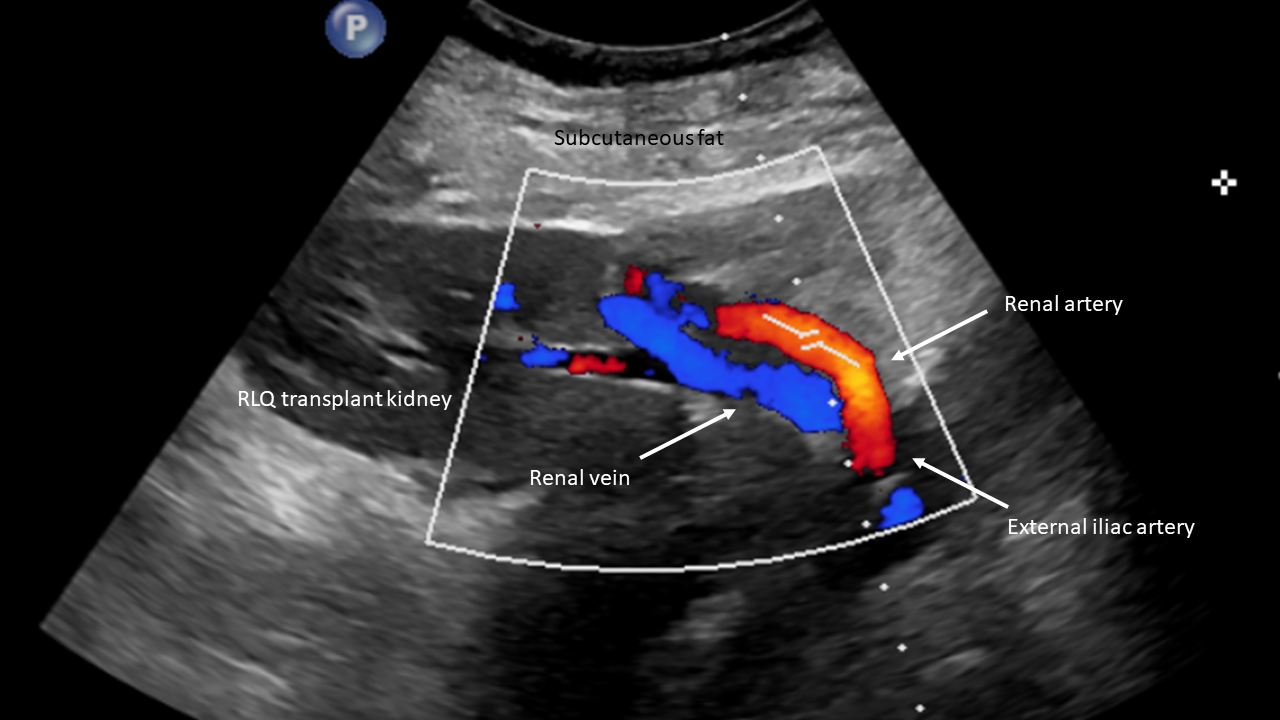

When evaluating kidney transplants, a few additional considerations are worth discussing. Compared to the deep retroperitoneal position of native kidneys, kidney transplants are in a superficial extraperitoneal location placed in either iliac fossa (usually the right). This allows the usage of higher frequency probes with associated higher spatial resolution. When assessing extrarenal vessels in transplanted kidneys, it is imperative to know the surgical, vascular anatomy, and vascular anastomosis site since multiple surgical variations exist. The main renal artery is most commonly anastomosed to the external iliac artery; however, the internal iliac artery, common iliac artery, or aorta are also potential anastomoses sites.[12][13]

Complications

There are no significant complications associated with this examination. As mentioned above, several factors may, however, limit the utility and evaluation of the study.

Clinical Significance

Gaining a thorough understanding of renal Doppler ultrasound is critical in the assessment and diagnosis of renal diseases. Some of the commonly encountered pathologies will be discussed briefly to illustrate important concepts in renal Doppler imaging.

Renal artery stenosis: Renal artery stenosis (RAS), of which the vast majority is related to atherosclerosis, represents the most common cause of secondary hypertension and is the most common vascular complication in renal transplants.[3][12] Doppler US criteria for RAS can be split into direct and indirect signs. Direct signs are seen at the site of the stenosis and include the following criteria: A PSV > 200 cm/s (compatible with ≥ 60% stenosis), increased renal/aortic PSV ratio (>3.5:1), absence of Doppler US signal consistent with occlusion, and aliasing with post-stenotic turbulent flow/spectral broadening. Indirect downstream effects can be observed distal to the stenosis site and are especially important in renal artery US imaging since the stenosis site itself might be not well seen; specifically, a “parvus-tardus” waveform (blunted and delayed systolic upstroke), which will be most evident in the peripheral renal vasculature. This corresponds to an AI < 3 m/s, an AT > 70 msec and a decreased RI < 0.5.[3][14]

Renal artery thrombosis and segmental infarction: Although renal artery thrombosis (RAT) is relatively uncommon, if not treated immediately, it can lead to a devastating outcome, especially if there is a lack of multiple renal arteries. A complete absence of flow is seen on Doppler imaging within the renal artery associated with an abnormal spectral waveform, including the absence of diastolic flow and a markedly reduced amplitude. When encountering this scenario, it is crucial to adjust the color and power Doppler settings to avoid false-positive results. However, it should also be noted that US has a lower sensitivity in detecting renal infarctions when compared to CT or MRI, especially small infarctions. Acutely infarcted kidneys may be enlarged and heterogeneous on the grayscale US. A lack of color or power Doppler flow might be seen in the affected renal parenchyma; if it is a focal infarct, this presents as hypoechoic wedge-shaped regions.[3][12][15][16]

Renal vein thrombosis: Renal vein thrombosis (RVT) can be categorized into bland or tumor thrombus and comprises partial occlusion of the vein versus complete obstruction. In transplanted kidneys, RVT constitutes a catastrophic complication, with most patients developing subsequent graft failure. Clinically RVT presents with hematuria or signs of renal failure such as rising creatinine or anuria. On US, an increase in renal size is often observed due to associated venous congestion. Color Doppler of the renal vein demonstrates either filling defects indicating partial occlusion or complete absence of flow consistent with obstruction. Spectral Doppler demonstrates a reversal of diastolic flow in the main renal artery, noting that, in transplant patients, a reversal of diastolic flow can also be seen with acute rejection, acute tubular necrosis, and extrarenal compression.[3][12][17]

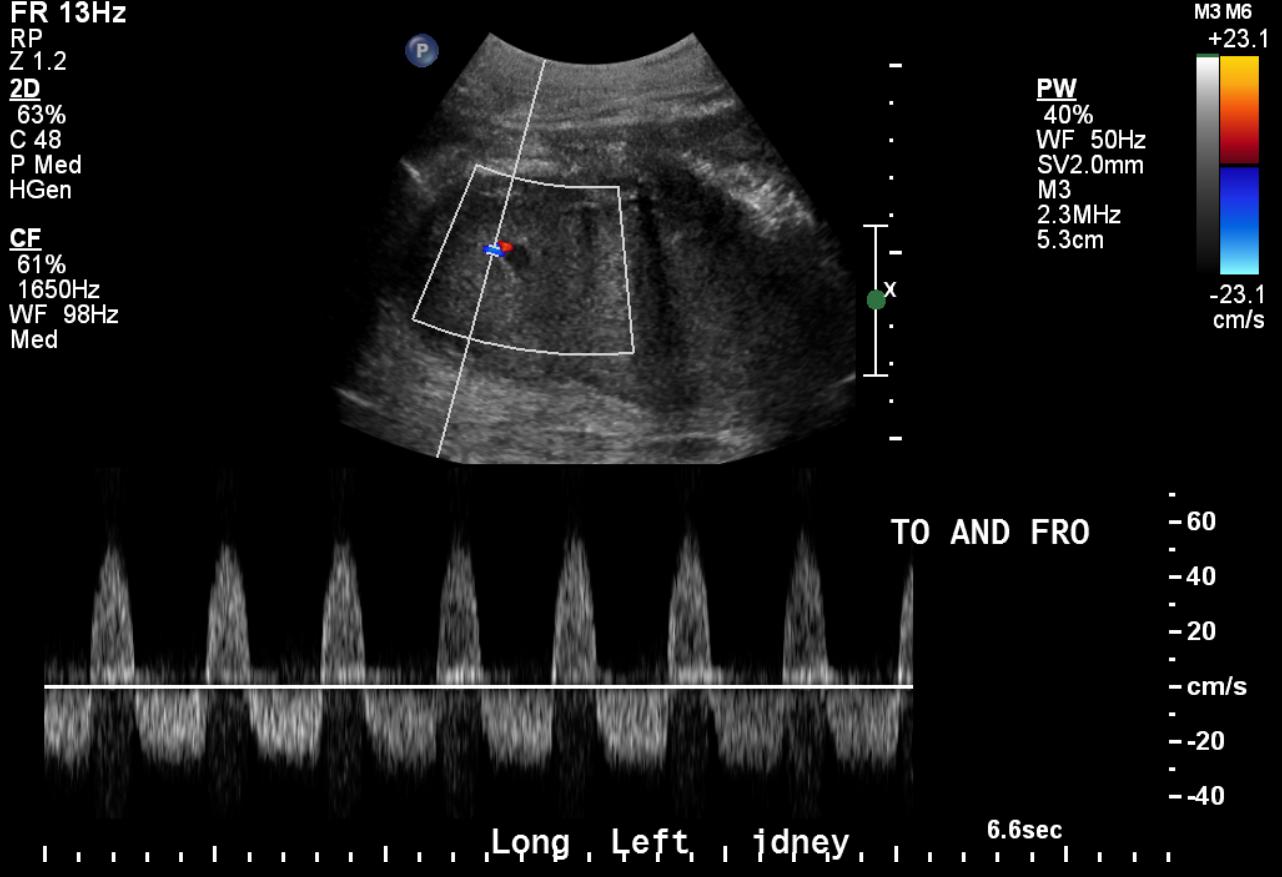

Pseudoaneurysm and Arteriovenous Fistula: Pseudoaneurysms (PSAs) are frequently the result of iatrogenic trauma such as biopsies or interventions and can be intrarenal/parenchymal in location. They may remain asymptomatic and are incidentally detected or present with pain, bleeding, and/or hematuria. They present as simple or complex cystic outpouching on the grayscale US, and it is of utmost importance to evaluate with color Doppler if you encounter renal cystic structures to rule out a vascular lesion. Color Doppler shows the “yin-yang” sign, which indicates bidirectional/swirling blood flow. Spectral Doppler might demonstrate the classic “to-and-fro” flow in the PSA neck. When a PSA is encountered, it is necessary to evaluate a surrounding hematoma, extraluminal blood flow, and an arteriovenous fistula (AVF) that might coexist. Findings suggesting the simultaneous presence of an AVF include arterialized venous flow in the draining vein indicating an abnormal direct communication between the artery and vein that is bypassing the capillary bed.[3][12][15]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Appropriate indications for a specific imaging study or clinical condition are extremely important in healthcare nowadays to avoid unnecessary costs and the use of resources. In addition, quick and effective communication between clinicians and radiologists are key elements to make an accurate diagnosis and achieve a good outcome for the patient eventually. Furthermore, in a modern healthcare system, multiple other providers are often involved in patient care when performing a Doppler ultrasound, such as sonographers, schedulers, and nurses. The leadership role in this process pertains to the physician who interprets the study and oversees the entire proceedings to guarantee the highest quality of imaging and patient care at all times.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Expert Panel on Urologic Imaging:, Taffel MT, Nikolaidis P, Beland MD, Blaufox MD, Dogra VS, Goldfarb S, Gore JL, Harvin HJ, Heilbrun ME, Heller MT, Khatri G, Preminger GM, Purysko AS, Smith AD, Wang ZJ, Weinfeld RM, Wong-You-Cheong JJ, Remer EM, Lockhart ME. ACR Appropriateness Criteria(®) Renal Transplant Dysfunction. Journal of the American College of Radiology : JACR. 2017 May:14(5S):S272-S281. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2017.02.034. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28473084]

Expert Panels on Urologic Imaging and Vascular Imaging:, Harvin HJ, Verma N, Nikolaidis P, Hanley M, Dogra VS, Goldfarb S, Gore JL, Savage SJ, Steigner ML, Strax R, Taffel MT, Wong-You-Cheong JJ, Yoo DC, Remer EM, Dill KE, Lockhart ME. ACR Appropriateness Criteria(®) Renovascular Hypertension. Journal of the American College of Radiology : JACR. 2017 Nov:14(11S):S540-S549. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2017.08.040. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29101991]

Al-Katib S, Shetty M, Jafri SM, Jafri SZ. Radiologic Assessment of Native Renal Vasculature: A Multimodality Review. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2017 Jan-Feb:37(1):136-156. doi: 10.1148/rg.2017160060. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28076021]

Leslie SW, Sajjad H. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Renal Artery. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29083626]

Türkvatan A, Ozdemir M, Cumhur T, Olçer T. Multidetector CT angiography of renal vasculature: normal anatomy and variants. European radiology. 2009 Jan:19(1):236-44. doi: 10.1007/s00330-008-1126-3. Epub 2008 Jul 30 [PubMed PMID: 18665365]

Drelich-Zbroja A, Kuczyńska M, Światłowski Ł, Szymańska A, Elwertowski M, Marianowska A. Recommendations for ultrasonographic assessment of renal arteries. Journal of ultrasonography. 2018:18(75):338-343. doi: 10.15557/JoU.2018.0049. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30763019]

American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine, American College of Radiology. AIUM practice guideline for the performance of renal artery duplex sonography. Journal of ultrasound in medicine : official journal of the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine. 2009 Jan:28(1):120-4 [PubMed PMID: 19106371]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAmerican Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine, American College of Radiology, Society for Pediatric Radiology, Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound. AIUM practice guideline for the performance of native renal artery duplex sonography. Journal of ultrasound in medicine : official journal of the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine. 2013 Jul:32(7):1331-40. doi: 10.7863/ultra.32.7.1331. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23804358]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMarsico M, Gabbani T, Casseri T, Biagini MR. Factors Predictive of Improved Abdominal Ultrasound Visualization after Oral Administration of Simethicone. Ultrasound in medicine & biology. 2016 Nov:42(11):2532-2537. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2016.06.024. Epub 2016 Jul 29 [PubMed PMID: 27481017]

Pozniak MA, Zagzebski JA, Scanlan KA. Spectral and color Doppler artifacts. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 1992 Jan:12(1):35-44 [PubMed PMID: 1734480]

Hélénon O, Correas JM, Chabriais J, Boyer JC, Melki P, Moreau JF. Renal vascular Doppler imaging: clinical benefits of power mode. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 1998 Nov-Dec:18(6):1441-54; discussion 1455-7 [PubMed PMID: 9821193]

Rodgers SK, Sereni CP, Horrow MM. Ultrasonographic evaluation of the renal transplant. Radiologic clinics of North America. 2014 Nov:52(6):1307-24. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2014.07.009. Epub 2014 Sep 4 [PubMed PMID: 25444108]

Galgano SJ, Lockhart ME, Fananapazir G, Sanyal R. Optimizing renal transplant Doppler ultrasound. Abdominal radiology (New York). 2018 Oct:43(10):2564-2573. doi: 10.1007/s00261-018-1731-9. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30121777]

Spyridopoulos TN, Kaziani K, Balanika AP, Kalokairinou-Motogna M, Bizimi V, Paianidi I, Baltas CS. Ultrasound as a first line screening tool for the detection of renal artery stenosis: a comprehensive review. Medical ultrasonography. 2010 Sep:12(3):228-32 [PubMed PMID: 21203601]

Baxter GM. Imaging in renal transplantation. Ultrasound quarterly. 2003 Sep:19(3):123-38 [PubMed PMID: 14571160]

Low G, Crockett AM, Leung K, Walji AH, Patel VH, Shapiro AM, Lomas DJ, Coulden RA. Imaging of vascular complications and their consequences following transplantation in the abdomen. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2013 May:33(3):633-52. doi: 10.1148/rg.333125728. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23674767]

Lockhart ME, Wells CG, Morgan DE, Fineberg NS, Robbin ML. Reversed diastolic flow in the renal transplant: perioperative implications versus transplants older than 1 month. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2008 Mar:190(3):650-5. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2666. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18287435]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence