Introduction

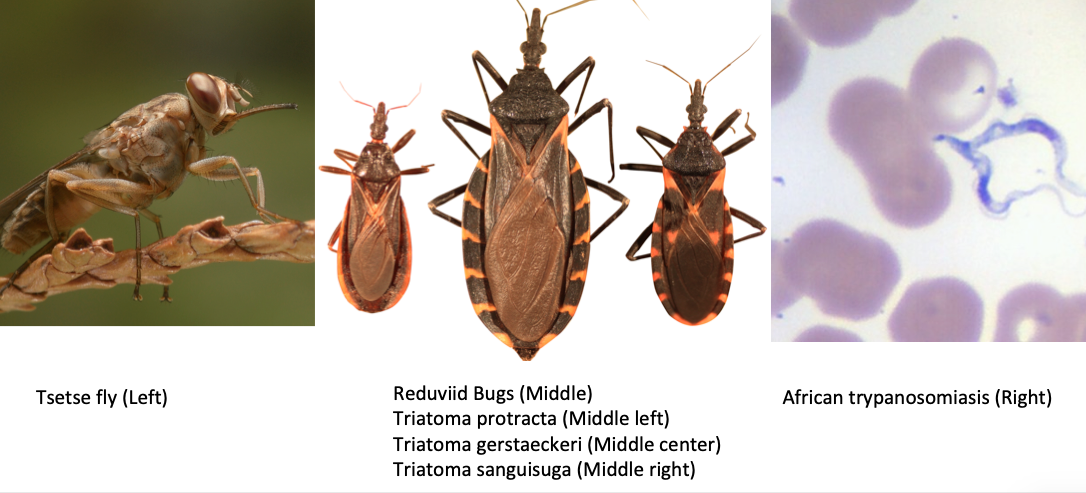

African trypanosomiasis, also known as human African trypanosomiasis (HAT) and sleeping sickness, is caused by 1 of 2 Trypanosoma brucei protozoa transmitted by the tsetse fly in sub-Saharan Africa. The disease is considered a neglected tropical disease and remains a nearly universal fatal disease if not treated.[1][2][3]

Etiology

Trypanosoma brucei is usually transmitted to humans from an infected tsetse fly.[4]

Epidemiology

HAT Trypanosoma brucei gambiense is a disease endemic to western sub-Saharan Africa, while HAT Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense affects areas of eastern sub-Saharan Africa. As the 2 diseases are spread by different tsetse subspecies, the 2 diseases do not overlap, though Uganda has both variants within its borders. Estimates of the disease prevalence have proven to be difficult, though some studies estimate 20,000 individuals are affected by the disease, with nearly 9100 dying from both variants in 2010.

African trypanosomiasis can occur at any age and can affect all races.[5]

Pathophysiology

Once the tsetse fly ingests the trypanosomes, they multiply and develop into epimastigotes. Humans are infected after the bite from a tsetse fly. The injected parasites then rapidly divide in the bloodstream and lymphatics. Eventually, the parasite enters the central nervous system (CNS) and causes neurological and behavioral symptoms.

The trypanosomes evade the host's immune system because of extensive antigenic variation of the glycoproteins located on the surface of the parasite. During this time, the parasites invade almost every organ in the body.

Some individuals may develop a severe hypersensitivity reaction to the parasite that leads to itching, swelling, and edema.

In the liver, there may be portal infiltration and fatty degeneration.

When the heart is invaded, arrhythmias may develop leading to death.

When the brain is involved, it may lead to meningoencephalitis, bleeding, edema, and granulomatous lesions.

History and Physical

HAT Trypanosoma brucei gambiense

The initial stage often presents with a painless eschar at the point of infection, though this is often not recalled due to a prolonged asymptomatic course. Patients often have an indolent first stage marked by posterior cervical lymphadenopathy (Winterbottom’s sign), headaches, malaise, and arthralgias. As the disease progresses to the second stage, patients will develop somnolence, fatigue, neurological deficits, tremors, ataxia, seizures, comas, and eventually death.

HAT Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense

Affected individuals typically present after inoculation with a painful eschar and a rapidly progressing illness marked by fevers, rash, fatigue, and myalgias. Within a few weeks to months, the disease progresses to the second stage, with symptoms identical to that of HAT Trypanosoma brucei gambiense but with a much-accelerated course that quickly leads to death.

Physical Findings

- Induration at the bite site

- In light-skinned individuals, one may see skin lesions (trypanids)

- Generalized lymphadenopathy which is most prominent in the axilla and inguinal area.

- Fever

- Tachycardia

- Edema

- Splenomegaly

- Disorientation and altered mental status

- Psychosis

- Stupor and coma

Evaluation

HAT Trypanosoma brucei gambiense can be screened for with the card agglutination trypanosoma test (CATT), a study that examines serum for antigen and that carries a sensitivity of 91% and specificity of 97%. Both species can also be identified with Giemsa-stained blood, lymph node aspirates, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) fluid. All patients with suspected HAT should be screened for CNS involvement with a lumbar puncture; CSF fluid should be tested for trypanosomes, leukocytosis, and trypanosome IgM. In the second-stage infections, the number of parasites in congestive heart failure (CHF) can be very low. World Health Organization (WHO) diagnostic criteria for suspected second stage trypanosomiasis, therefore, consists of either the presence of trypanosomes in CSF fluid or greater than 5 white blood cells (WBCs) per microliter of fluid in a suspected case.

In many hospitals, in Africa, a blood smear is often done as it will reveal the mobile trypanosomes. Blood smears are often positive in early disease when the number of circulating parasites is very high.

Lymph node aspiration is sometimes done to identify the parasite and may yield positive results.

CT scan and MRI of the brain frequently reveal massive cerebral edema and enhancement of the white matter.

Treatment / Management

The early stage management requires treatment of fever and malaise. Close monitoring of the CNS status is necessary. Sometimes, patients may require intubation and mechanical ventilation as they can not maintain a patent airway.[6][7][8]

HAT Trypanosoma brucei gambiense: Treatment during the first stage consists of pentamidine. After patients develop CNS symptoms, patients will require eflornithine and nifurtimox. If no response is achieved, providers may resort to melarsoprol.

HAT Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense: Treatment of the initial stage consists of suramin while treatment of the second stage consists of melarsoprol.

Most studies today show that combination therapy with melarsoprol and nifurtimox is more effective than either solo therapy.

Differential Diagnosis

- Amebic meningoencephalitis

- Constrictive pericarditis

Prognosis

If the infection is treated during the early stage, recovery is possible in most patients. However, if the patient presents with stage 2 disease, the CNS involvement usually is fatal. Today, the cure rate with the drug melarsoprol is more than 90%.[9]

Complications

- Severe wasting

- Anemia

- Fatigue

- Stupor

- Psychosis

- Aspiration pneumonitis

- Death

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

- Patients need long-term monitoring to ensure they have not developed any complications.

- The patients should be followed up with regular blood smears and lumbar puncture every three months for the first 12 months and then at six monthly intervals.

- If relapse is noted, then repeat treatment with melarsoprol is needed.

- Side effects of melarsoprol include hypertension, encephalopathy, neuropathy, cardiac damage, and vomiting.

- Side effects of suramin include emesis, neuropathy, kidney damage and blood dyscrasias.

- Side effects of eflornithine include pancytopenia, seizures, and hearing impairment.

- Because of these severe side effects, patients need to be closely monitored and the dose adjusted or discontinued.

Consultations

If a patient is suspected of having African trypanosomiasis, immediate consultation with an infectious disease expert is recommended.

If the patient is in the United States, one should contact the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Deterrence and Patient Education

- There is no vaccine yet available.

- Tourists should avoid travel to endemic areas and avoid wearing dark contrasting colors.

- The tsetse fly is not affected by any insect repellant.

Pearls and Other Issues

Melarsoprol is an arsenical compound that must be administered in propylene glycol. Administration of the drug is painful and carries multiple adverse effects, the most serious consisting of the melarsoprol-induced encephalopathic syndrome. This occurs in 1.5% to 28% of treatments and results in nearly a 50% mortality rate. All patients receiving the medication should, therefore, be monitored in a hospital setting.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

African trypanosomiasis, also known as human African trypanosomiasis (HAT) and sleeping sickness, is caused by 1 of 2 Trypanosoma brucei protozoa transmitted by the tsetse fly in sub-Saharan Africa. The disease is considered a neglected tropical disease and remains a nearly universal fatal disease if not treated. However, most healthcare workers in North America are unlikely to see a case in their lifetime. But it is still important to consider this disorder in the differential in a patient coming from the tropics. The best advice is to immediately consult with infectious disease on how to make the diagnosis and manage the patient.