Continuing Education Activity

Temporary abdominal closure (TAC) is a crucial strategy in surgical scenarios where primary fascial closure is challenging, often due to peritonitis, abdominal compartment syndrome, or trauma. Various TAC techniques, including negative pressure wound therapy, dynamic retention sutures, and mesh applications, provide provisional closure until delayed primary fascial closure is feasible. This process helps prevent complications like ventral hernias and optimizes patient outcomes. Clinicians managing open abdomen cases must understand and master these techniques, considering individual patient factors and risks.

Clinicians engaging in this continuing education activity on TAC gain comprehensive insights into various TAC techniques, their mechanisms, applications, and potential complications. By the end of this activity, participants have enhanced competence in identifying, differentiating, and implementing appropriate TAC strategies. Participation in this course fosters collaboration among healthcare professionals, enhancing interprofessional competence. By understanding and mastering TAC techniques, the interprofessional team ensures holistic patient care, navigating the complexities of open abdomen scenarios to improve overall outcomes.

Objectives:

Identify situations during laparotomies where primary fascial closure may not be feasible, necessitating the need for temporary abdominal closure.

Differentiate between various temporary abdominal closure techniques, understanding their unique mechanisms, applications, and potential complications.

Select the optimal temporary abdominal closure strategy based on the clinical presentation, underlying pathology, and patient characteristics.

Communicate and collaborate effectively with members of the interprofessional healthcare team to develop coordinated strategies for implementing temporary abdominal closure techniques in open abdomen scenarios.

Introduction

After a laparotomy, primary closure of the abdominal fascia is typically the preferred approach. However, situations may arise where complete fascial closure becomes unattainable, necessitating the surgeon to leave the abdomen open. This open abdomen poses a significant challenge and is associated with mortality rates exceeding 30%. Common scenarios leading to an open abdomen include peritonitis-induced bowel edema, abdominal compartment syndrome, and damage control surgery for trauma patients with intraabdominal bleeding. Temporary abdominal closure (TAC) techniques become imperative in such cases, aiming to provide a provisional solution until the abdominal fascia can be closed. Various TAC techniques are employed to address the challenges posed by the open abdomen. These techniques include negative pressure wound therapy, dynamic retention sutures, plastic silo (Bogotá bag), mesh/sheet, loose packing, skin approximation, and zipper. Each technique offers distinct advantages in maintaining tension on the fascial edges while accommodating varying clinical scenarios. Understanding and mastering these TAC techniques are critical for clinicians managing patients with an open abdomen, as failure to achieve delayed primary fascial closure puts patients at risk of developing ventral hernias with associated burdens and potential surgical complications. While the strategy for TAC or permanent abdominal closure should consider individual patient factors and risks, evidence-based comparative trials are lacking, highlighting the need for further research in this domain. The subsequent article explores TAC techniques' intricacies, mechanisms, applications, and potential complications.

Technique or Treatment

When a decision is made to leave the abdomen open after surgery, the exposed area must be covered temporarily with a TAC. This process controls fluid loss and provides tension across the fascia so that it does not shrink or retract, a phenomenon called loss of domain. Over the past 30 years, surgical approaches to managing an open abdomen have significantly improved. The best method of TAC remains unclear, as no single method fits every clinical situation. The following are various techniques of TAC:

Simple Packing

This method involves placing nonadherent wet gauze or hydrophilic dressings directly on the abdominal contents without sutures, leaving the abdomen open for peritoneal drainage. Dressing changes and abdominal lavage were performed daily in the intensive care unit.

Skin-Only Closures

Temporary skin-only closure techniques utilize the skin to stabilize the abdominal wall while containing the abdominal viscera. These methods employ either a series of towel clips or a running monofilament suture. The towel clip closure stands are the fastest technique for temporary closure. The application involves placing towel clips on the skin approximately 1 cm apart, with the handles oriented towards the center, allowing for coverage by an adhesive plastic drape and minimizing artifact interference in subsequent radiographs (see Image. Skin-Only Closure). Whether using towel clips or suture closure, both methods are rapid, cost-effective, and readily accessible. However, due to the skin's relatively low bursting pressure, these techniques come with increased risks of complications such as evisceration, skin injury or loss, infection, and recurrent abdominal compartment syndrome. Other issues include the inability to check the abdominal contents, and if towel clips are used, artifacts in imaging (ie, chest x-rays) are unavoidable. Given the elevated complication rates, including abdominal compartment syndrome incidence ranging from 13% to 36%, these techniques have largely fallen out of favor in contemporary practice.[2]

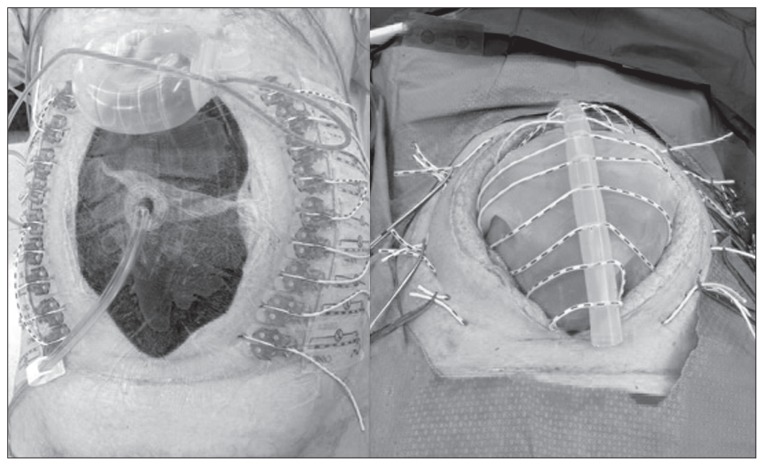

Dynamic Retention Sutures

This is also known as an abdominal reapproximation anchor (ABRA®) and involves plastic tubes inserted through the abdominal wall away from the fascial edge and held with an adhesive button (see Image. ABRA® System). By pulling on the tubes on both sides of the defect, a staged approximation can be achieved. This placement of a temporary retention suture that could sequentially tighten the abdominal wall to minimize loss of domain in the open abdomen was first described more than 20 years ago.[3] The advantage is that it provides fascial tension while preserving the fascial edge for delayed primary closure. Furthermore, it is relatively easy to apply. The drawbacks are the costs, the possibility of abdominal compartment syndrome formation, and the increased risk of enteric fistula formation by tube pressure onto the bowel.

Silo Techniques

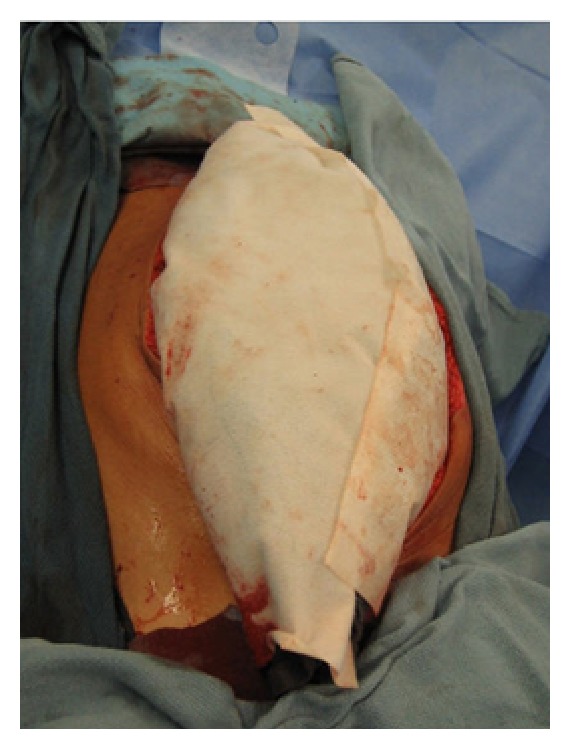

Silo techniques in TAC involve suturing a large, sterilized, translucent bag to the abdominal fascia or skin. A dialysate, irrigation, or intravenous (IV) bag can be used. The latter is more commonly known as a Bogotá bag, named after its observation in Bogotá, Colombia; it involves utilizing a pre-sterilized, soft 3 L IV bag that is cut to an oval shape and stapled with a standard skin stapling device or sutured with monofilament suture to the skin edges of the wound (see Image. Silo Technique). Sterile, antibiotic-soaked towels are placed over the silo, which is then covered with an iodine-impregnated adhesive plastic drape. The wound is inspected, and the dressing is changed every 24 hours. Despite its simplicity and low cost, this technique is time-consuming and poses challenges in controlling fluid losses. These potential challenges may require upsizing due to increased intraabdominal pressure, leading to operative replacement with a larger bag. While offering a cost-effective solution for containment when skin-only closure is impossible, it has limitations. The Bogotá bag does not prevent abdominal wall retraction or allow effective removal of abdominal fluids, necessitating a subsequent procedure for removal and definitive closure. Despite its drawbacks, the Bogotá bag technique has been associated with a wide range of primary closure rates (12% to 82%), low enteric fistula rates (0% to 14.4%), and considerable hospital morbidity, particularly in cases of intraabdominal sepsis, with a 39% primary fascial closure rate and a 12% in-hospital mortality rate reported in 1 study. Sixty percent of patients developed ventral hernias within a 48-month follow-up.[2]

Mesh

Repair materials in TAC for open abdomen management include absorbable and permanent synthetic options. Permanent synthetic prostheses, such as polypropylene and polytetrafluoroethylene mesh, offer protection to abdominal wall tissues, prevent lateral fascial retraction, and reduce incisional abdominal wall hernia incidence (see Image. Polypropylene Mesh Abdominal Closure and Image. Polytetrafluoroethylene Mesh Abdominal Closure). However, complications like wrinkling, infection, hernia, mesh extrusion, and enteric fistula may arise. These complications can also make reoperation more challenging. Absorbable meshes like polyglactin 910 and polyglycolic acid are resistant to infection and pliable, but their use in TAC may result in fistula formation and intraabdominal abscesses. The absorbable mesh forms a granulation tissue bed for skin grafting, while nonabsorbable meshes can be initially loosely sutured, allowing for visceral swelling prevention. Nonabsorbable meshes enhance primary closure rates of 33% to 89%. Careful consideration of material properties and potential complications is crucial in selecting an appropriate strategy for TAC.

Mesh bridging: Using a rapidly absorbable, biologic, or synthetic mesh placed as an interposition graft between the fascial edges has been described in the literature. In the setting of massive loss of domain, it may be the only technique to facilitate coverage of the intestines and facilitate granulation to allow skin grafting and later reconstruction.[4][5]

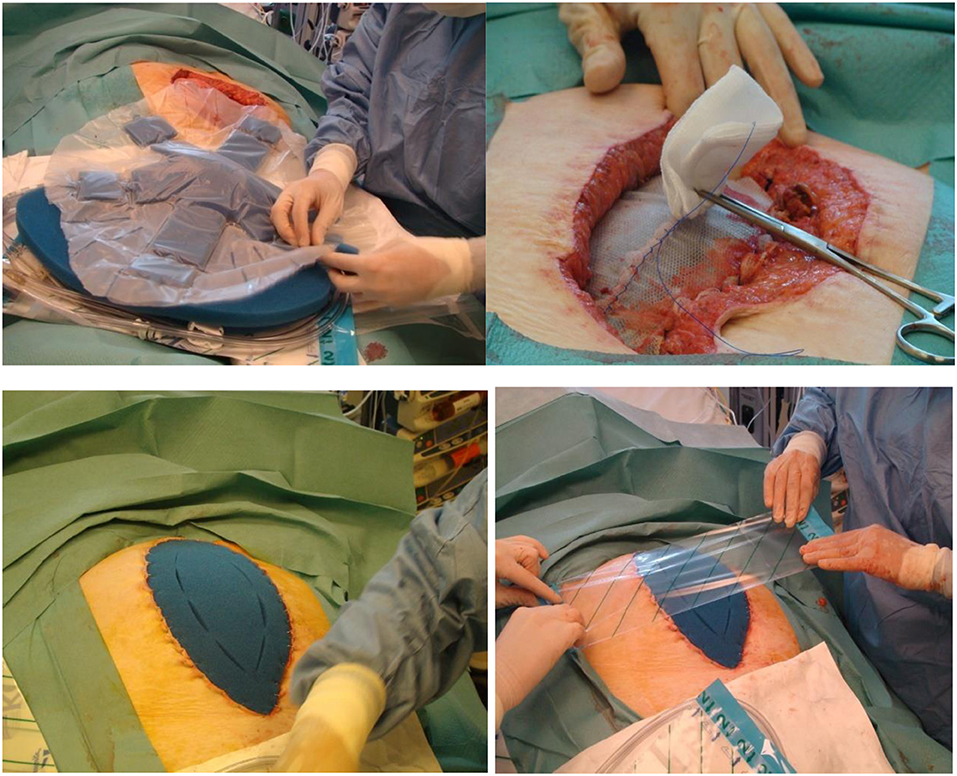

Mesh-mediated fascial traction is a technique where the mesh is sewn to the opposing fascial edges and sequentially tightens the anterior abdominal wall.[6] The most commonly known version is the Wittmann patch (see below). Various meshes have also been sewn in an underlay fashion, as well as an overlay on top of the fascia.[7][8][9] Additional benefits may come from combining this therapy with a fluid removal system such as the vacuum-based dressing (see Image. Vacuum-Assisted Mesh-Mediated Fascial Traction).

Wittmann Patch

The technique involves a detachable system where the Wittmann patch sheet is laterally sutured to the abdominal fascia, and closure at the midline is achieved with a velcro-like mechanism by tightening it every 24 to 48 hours until the fascia is approximately 2 to 4 cm apart (see Image. Wittmann Patch). The sheet is removed, and definitive closure is primarily used to close the fascia. This facilitates delayed fascial closure, showing a high success rate ranging from 78% to 100%. Despite its popularity, the Wittmann patch is more expensive (about $1440 per patient), requires suturing to the abdominal fascia, and may not effectively evacuate peritoneal fluid, presenting potential challenges in abdominal wound drainage.

Zipper

A mesh or sheet with a sterilized zipper is sutured between the fascial edges. This technique is comparable to the mesh technique and allows for easy access.

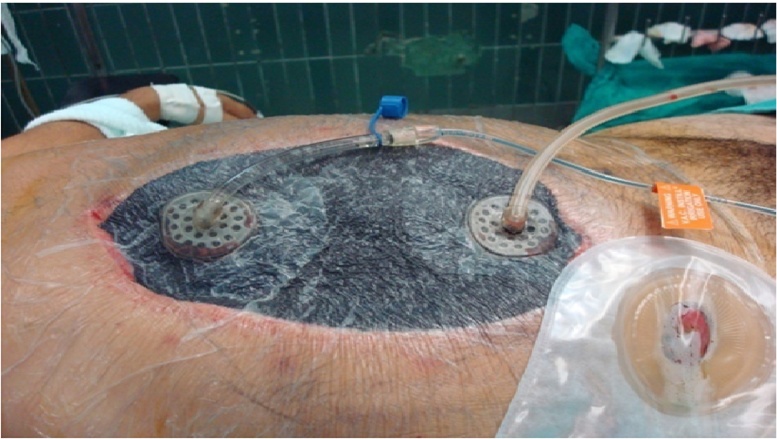

Negative Pressure Wound Therapies

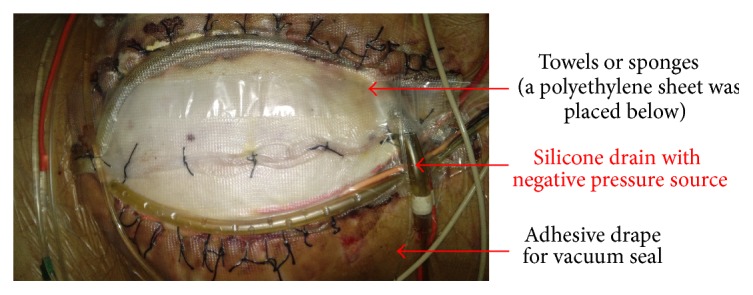

Towel-based negative pressure wound therapies (NPWTs), also known as vacuum packs, were first described by Barker's group in 1995. This technique uses a surgical towel affixed to a polyethylene sheet strategically positioned between the anterior abdominal wall's viscera and the posterior aspect. Small slit perforations are cut in the elastic drape to facilitate fluid drainage from the abdomen. Drainage tubing, situated over the towel, is connected to a closed-suction drainage system, ensuring effective capture of the expelled fluid. Applying an outer adherent elastic layer adeptly covers the abdominal wall defect (see Image. Vacuum Pack Dressing). There are institution-specific variations as well.

The dressings associated with towel-based systems are known for their simplicity and cost-effectiveness. While proficient in controlling abdominal fluid, this system lacks comprehensive suction capabilities throughout the entire abdomen, potentially resulting in fluid accumulation within the abdominal cavity. Notwithstanding this limitation, the system demonstrates relative compliance, enabling it to accommodate mild increases in intraabdominal volume without inducing elevated intraabdominal pressure.

Sponge-based NPWTs use a perforated silastic sheet positioned between the bowel and abdominal wall, and a trimmed sponge is utilized to fill the subcutaneous abdominal defect. An outer self-adherent skin drape incorporates a suction port connected to a proprietary suction device. Although more expensive than the towel-based negative pressure system, the sponge-based approach provides more uniform suction throughout the peritoneal cavity. This approach may be more effective in preventing intraabdominal fluid accumulation.

NPWT remains preferable to simple silastic dressings such as the Bogotá bag to achieve fascial closure.[10] Numerous studies endorse these techniques, reporting high fascial closure rates, particularly with the AB-Thera®. Randomized controlled studies have demonstrated that dynamic therapy (ie, ABRA and MMFT) with NPWT is better for fascial closure than just NPWT alone (see Image. Dynamic Closure of Open Abdomen).[11] The studies comparing the different dynamic techniques are mostly retrospective observational studies. Most recently, an observational cohort study meta-analysis demonstrated 93% fascial closure with NPWT+ABRA versus 72% with NPWT+MMFT.[12]

In addition to increased fascial closure rates, another distinct advantage of this technique is the ability to allow for NPWT irrigation (NPWT-I), which has been suggested to help clear inflammatory cytokines in treating a septic cause for the open abdomen (see Image. VAC® Plus Instillation Assembly).[13][14] One review of 48 cases where NPWT-I was used showed added benefits compared to traditional methods such as the Bogotá bag, Wittmann patch, or NPWT alone in managing the open abdomen for severe abdominal sepsis. NPWT-I in patients with severe abdominal sepsis had promising results of higher fascia closure rates, lower mortality, and reduced hospital and intensive care unit length of stay with no complications attributed to this therapeutic approach.[15]

Commercially available sponge-based NPWT kits include:

- V.A.C.® Therapy (KCI (now part of 3M), San Antonio, Texas, USA)

- This comprises an inner plastic-encased sponge in direct contact with the viscera. This plastic interface shields the bowel, prevents adhesion formation, and is perforated to allow fluid passage. A macroporous "black" sponge is applied over the inner layer, in contact with the fascia, and can be secured with skin staples for approximation. This layer is then covered with an adhesive occlusive dressing, and a suction drainage device evacuates the superficial foam layer.

- AB-Thera® (ABThera system, KCI (now part of 3M), San Antonio, Texas, USA)

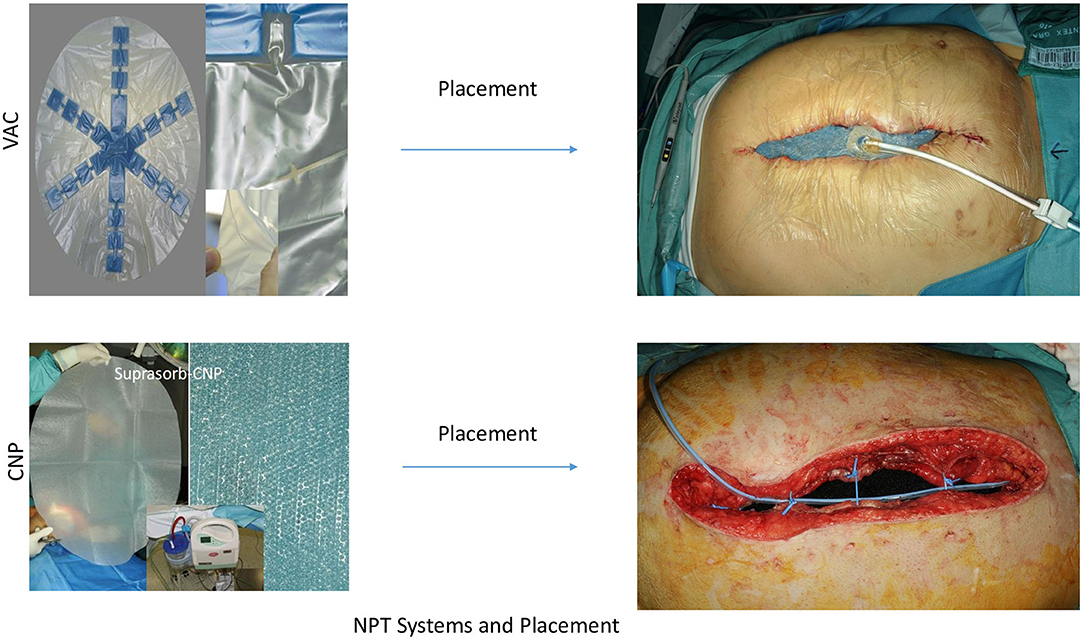

- This improvement on the system described above involves a large visceral protective layer with a polyurethane film-covered central foam structure. Six arms of polyurethane foam extend from the center to envelop the viscera, reaching into the paracolic gutters and draining fluid from various abdominal areas. This component, known as the "spider drape," is crucial in effective peritoneal fluid evacuation. Other system parts include an oval-shaped sponge that fits atop the exposed viscera, a large adhesive drape for an airtight seal, and a connecting pad allowing for negative suction (see Image. AB-Thera® and Suprasorb-CNP® Placements).

- Suprasorb-CNP® (Suprasorb CNP system, Lohmann & Rauscher, Austria-Germany)

- This system comes in an abdominal kit and works with closely spaced pores in a double-layer film placed around the viscera, shielding the intestine, liver surface, and pelvic cavity. The film was covered with polyurethane film-covered foam. In this system, however, a perforated silicon drainage tube was placed in this plane and connected with the suction pump, which served as the suction line. The subcutaneous space is then filled with rolled 6-inch gauze, and the skin around the wound is covered with a few layers of rolled gauze and then closed with the adhesive drape (see Image. AB-Thera® and Suprasorb-CNP® Placements).[16]

Proper utilization of negative pressure wound therapy is pivotal for successful abdominal closure, the prevention of enteric fistulas, and enhanced fluid removal from paracolic gutters. Ensuring the visceral protective layer envelops all visceral content without any foam contact is critical to achieving optimal results. The foam should be placed beneath the abdominal wall, atop the protective layer, to provide medial tension and closure while applying negative pressure through the foam. This method effectively minimizes fascial retraction and prevents loss of domain. In cases of compartment syndrome, use only a minimal strip of foam, or enough to cover the gap, on the incision to deliver negative pressure to the larger foam beneath the abdominal wall. The wound foam must be thicker than the subcutaneous layer.

Additionally, cutting the drape into strips aids in providing traction on the skin, facilitating the closure of the abdominal wall. To accomplish this, begin with 1 side of the strip and apply it to the skin, and then pull the other half to hold the wound together securely. Avoid the common error of having a tiny protective layer atop the viscera with a large foam opening, as this may inadvertently exacerbate the wound instead of achieving the intended temporary closure. Always follow these guidelines carefully to optimize the effectiveness of NPWT.

Facilitation of Fascial Closure

Hypertonic saline resuscitation: A protocol developed using hypertonic saline for resuscitation and NPWT has had improved success in early fascial closure in damage control laparotomy patients.[17][18]

Botulinum toxin A: This has been used as a method of chemical paralysis of the strong opposing forces of the lateral abdominal wall musculature used in complex abdominal wall reconstruction. One study by Zielinski et al described using this technique in the open abdomen to facilitate primary fascial closure.[19][20]

Clinical Significance

The clinical significance of TAC lies in its pivotal role in managing a spectrum of critical abdominal conditions, ranging from trauma and vascular emergencies to severe infections and complications of abdominal surgery. TAC is a strategic approach to controlling hemorrhage, preventing contamination, and alleviating abdominal compartment syndrome by providing a staged and controlled environment for surgical interventions. In severe infections, such as infected pancreatic necrosis or peritonitis, TAC allows for repeated access, debridement, and drainage, promoting effective source control. Additionally, TAC facilitates damage control surgery, enabling a staged approach in trauma scenarios to address immediate life-threatening issues before definitive closure. The technique is particularly valuable in managing ischemic bowel conditions, offering a "second-look" option to assess bowel viability and prevent unnecessary extensive resection. Overall, TAC is critical in optimizing patient outcomes, enhancing survival rates, and providing a tailored approach to complex abdominal pathologies.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Effective TAC management requires a collaborative and interprofessional approach involving physicians, advanced practitioners, nurses, and pharmacists. Physicians, particularly surgeons, play a pivotal role in decision-making regarding the timing and type of TAC, considering factors such as the patient's physiologic state and the underlying condition necessitating abdominal closure. Advanced practitioners, such as physician assistants and nurse practitioners, contribute by assessing patients, monitoring their response to treatment, and ensuring timely interventions. Nurses are crucial for day-to-day patient care, including wound management, infection control, and monitoring vital signs. Pharmacists are essential in medication management, ensuring appropriate antibiotic therapy, pain control, and addressing potential drug interactions.

Interprofessional communication is paramount for the cohesive functioning of the healthcare team. Regular and clear communication between team members helps ensure everyone is on the same page regarding the patient's condition, treatment plan, and any changes in care. Care coordination involves synchronizing efforts among professionals to provide seamless, patient-centered care. This includes scheduling procedures, managing follow-up appointments, and ensuring the patient receives comprehensive care. Healthcare professionals can improve outcomes, prioritize patient safety, and optimize team performance in TAC by fostering effective teamwork, open communication, and coordinated efforts.