Continuing Education Activity

Congenital ptosis is the presence of a droopy eyelid or eyelids since birth. The ptosis may not be immediately noticeable after birth but is usually noticeable within a few months. It can be unilateral or bilateral. Severe ptosis can cover the visual axis and lead to interference with vision development and may lead to amblyopia if not corrected. This activity describes the evaluation and management of congenital ptosis and highlights the interprofessional team's role in evaluating and treating patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiology of congenital ptosis.

- Review the evaluation of congenital ptosis.

- Outline management options available for congenital ptosis.

- Describe some interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance congenital ptosis and improve outcomes.

Introduction

"Ptosis," in Greek, means "falling." Congenital ptosis is a condition in which abnormal drooping of the upper eyelid occurs since birth or within the first year of life.[1] It poses a significant functional and psychosocial impact on the child and is cosmetically alarming to both the child and the parents.[1]

Ptosis can be divided into 2 broad categories:

- True ptosis: True ptosis can be further divided depending on the timing since the development of ptosis into

- Congenital ptosis: Congenital maldevelopment of the levator palpebrae superioris muscle resulting in drooping of the eyelid since birth or within the first year of life is known as congenital ptosis.[2]

- Acquired ptosis: abnormal drooping of the eyelid after one year of life due to any cause is known as acquired ptosis. Acquired ptosis can be due to neurogenic, myogenic, aponeurotic, or mechanical causes.[2]

- Pseudo ptosis: Apparent drooping of the eyelid due to ocular and adnexal causes is known as pseudoptosis.[2]

Etiology

Congenital ptosis is associated with maldevelopment of the levator palpebrae superioris muscle.[1][3] The causes of congenital ptosis include:

- Simple congenital ptosis: Idiopathic in origin.

- Congenital ptosis along with superior rectus muscle weakness: often termed double-elevator palsy

- Marcus Gunn Jaw-winking ptosis (congenital synkinetic ptosis): the external pterygoid's motor innervation is misdirected to supply the ipsilateral levator muscle. With mastication, the ipsilateral eyelid elevates.[4]

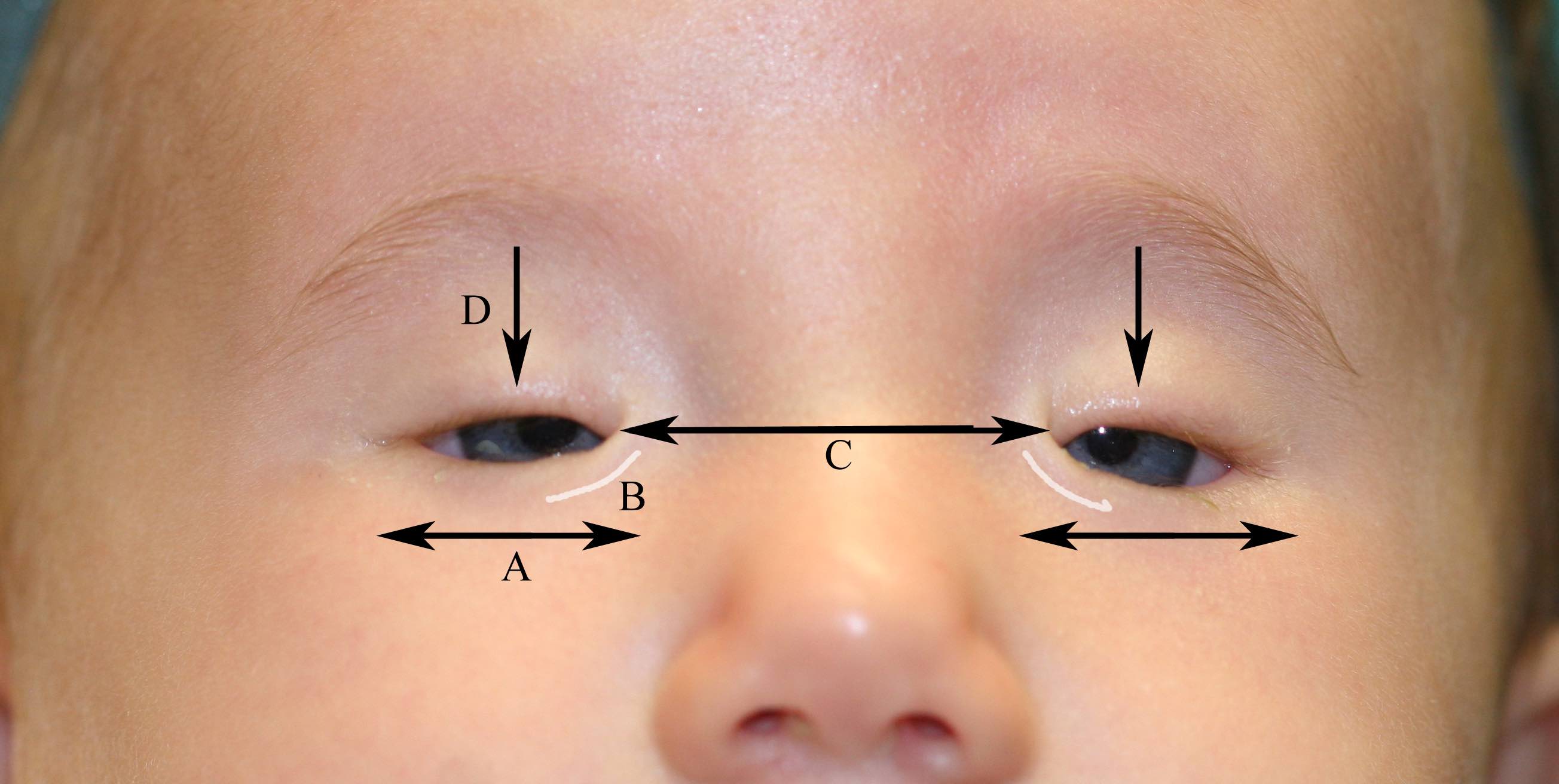

- Blepharophimosis Syndrome: This syndrome comprises blepharophimosis, congenital ptosis, epicanthus inversus, and telecanthus.[5]

- Other less common causes of congenital ptosis include:

- Third cranial nerve palsy[6]

- Horner Syndrome: characterized by mild ptosis, miosis, anhidrosis, ipsilateral heterochromia of the iris.[7]

- Secondary to birth trauma

- Periorbital tumors like plexiform neurofibromatosis, neuroblastoma, lymphoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, neuroma leukemias can induce mechanical ptosis.

- Pseudotumor of the orbit- ptosis induced by inflammatory disease of the orbit and secondarily affects the eyelids.

Epidemiology

In a study by Griepentrog et al., simple congenital ptosis was the most common form of congenital ptosis (81%), with the mean age of diagnosis of 3.7 years (0.1 to 16.7). Age and sex-adjusted incidence of simple congenital ptosis are 5.9 (4.6-7.2). Male preponderance was seen in patients with simple congenital ptosis (males 57%, females 43%). 11.7% of simple congenital ptosis gave a positive family history of ptosis. Bilateral involvement was seen in 4% of the cases, and out of all unilateral cases, 68% of patients had involvement of the left eye.[8]

Pathophysiology

There are three elevators of the upper eyelid:

- Levator Palpebrae Superioris

- It is the primary elevator of the upper eyelid.

- The oculomotor nerve supplies it.

- It originates from the lesser wing of the sphenoid.

- Along its path, it travels above the superior rectus muscle.

- It inserts into the upper eyelid skin, the upper tarsal plate's anterior surface, and the superior conjunctival fornix.

- Muller’s Muscle

- It is also known as the superior tarsal muscle.

- It is made of thin fibers of smooth muscle.

- The sympathetic nervous system innervates it.

- It is responsible for 1.5 to 2 mm elevation of the upper eyelid.

- Frontalis Muscle

- It acts as an accessory upper eyelid elevator.

- It is innervated by cranial nerve VII.

- It elevates the brow as well as the upper eyelid.

- It is attached to the skin of the eyebrows.

- It joins the galea aponeurotica below the coronal suture.

Congenital ptosis is associated with levator muscle dysgenesis, wherein the muscle fibers are replaced by adipose tissue and fibrous tissue. The elasticity of the muscle is lost, and it is neither able to contract nor relax properly. In downgaze, the ptotic eyelid in congenital ptosis is at a higher level because of the inability of the levator to relax sufficiently. In acquired ptosis caused by dehiscence of the levator aponeurosis, the upper eyelid is low in downgaze. There is corresponding increased action of the frontalis muscle and Muller muscle when the levator palpebrae superioris is not functioning properly.[3]

Blepharophimosis syndrome is a genetic disorder that is inherited as an autosomal dominant condition. The condition may occur sporadically or from de novo mutations in the FOXL2 gene.[5]

History and Physical

History and examination of all patients with ptosis should determine:

- age of onset and duration (congenital or acquired)

- any abnormal head position (e.g., chin lift)

- associated symptoms indicating the underlying cause

- the progression of ptosis as may be seen in conditions such as chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia (CPEO)

- variability of ptosis, which may be seen in conditions such as myasthenia gravis

Presenting Complaints

Patients usually present with a complaint of visible drooping of one or both eyelids, cosmetic concerns, diminution of vision, head posture abnormality, movement of the eyelid with the movement of the mouth, heaviness in the eyes, double vision in upgaze (if congenital ptosis is associated with superior rectus abnormality).

History

- Trauma (traumatic ptosis)

- Medical conditions (e.g., myasthenia gravis, myotonic dystrophy, CPEO, muscular dystrophies, hypertension, thyroid, and diabetes)

- Recurrent episodes (e.g., in recurrent 3rd nerve palsy secondary to ischemia caused by diabetes and hypertension)

- Contact lens wear (poorly fitting contact lenses can lead to secondary blepharospasm giving rise to falsely small palpebral fissures)

- Previous history of amblyopia therapy or the use of spectacles

- Drug intake (e.g., neostigmine)

- A recurrent stye, chalazion, vernal keratoconjunctivitis, giant papillary conjunctivitis, trachoma, eyelid tumor

Past Medical History

- Diabetes mellitus

- Hypertension

- Any neurological disorders

- Other associated congenital disabilities

- Thyroid disease

- Bleeding disorders (relevant if surgery is contemplated)

Past Surgical History

- Any strabismus surgery or ptosis correction surgery

- History of peribulbar block administration before any intraocular surgeries

Birth History

Delivery with the aid of forceps can be associated with an injury resulting in ptosis or facial palsy.

Family History

The presence of ptosis in family members should be ascertained, especially in blepharophimosis syndrome cases.

Examination of a Case of Ptosis

- A study of previous photographs helps determine the duration, severity, or variation of the ptosis.

- Handshake to rule out myotonic dystrophy.

- Visual acuity should be tested in all ptosis patients to rule out any associated refractive error and amblyopia, which should be addressed.

- Facial symmetry is determined.

- Chin elevation should be examined for in cases of bilateral ptosis.

- Periocular fullness should be assessed to determine the presence of any underlying conditions like hemangioma.

- Frontalis overaction will indicate compensation for the ptosis.

- Any periocular scars should be noted.

- Causes of pseudoptosis should be ruled out in ipsilateral and contralateral eyes before labeling it as a case of true congenital ptosis.

- Refraction is performed to rule out high myopia.

- Extraocular movement in primary and secondary gaze should be examined to rule out any extraocular muscle palsy or paresis.

- A cover-uncover test should be performed to rule out any strabismus associated with the ptosis.

- Direct and consensual light reflex should be checked to look for Horner's syndrome and third cranial nerve palsy.

- Dilated fundus examination should be done to rule out any associated vitreoretinal abnormalities.

- Movement of the upper eyelid while using mastication muscles should be noted to rule out the presence of Marcus Gunn Jaw winking phenomena.

In unilateral ptosis, elevate the ptotic eyelid to see if there is any droop of the opposite eyelid to confirm the diagnosis of true ptosis (based on Hering's law of equal innervation).

Bell's phenomenon should be checked in all patients before planning surgical intervention to assess the possible risk of exposure of the cornea after surgery. Bell's phenomena is a normal defense reflex of the eye wherein on closing the eyelids. The eye moves upwards and outwards. Bell's phenomena are graded into 3 categories :

- Good- on lifting the forcibly closed eye, less than one-third of the cornea is visible.

- Fair -on lifting the forcibly closed eye, one-third to one-half of the cornea is visible.

- Poor- one-half or more than half of the cornea is visible.

The corneal sensation and lagophthalmos should be checked in all ptosis patients before planning for surgery. Normal blink reflex and eyelid closure are essential to prevent dry eye and exposure keratitis after ptosis correction surgery.

Schirmer's test, tear film breakup time, and the tear meniscus should be documented before surgery as the presence of a dry eye may be a contraindication for ptosis correction.

The ice pack test should be tested to rule out myasthenia gravis.

Phenyeprine test: phenylephrine drops are used to assess Muller's muscle function in patients with mild to moderate ptosis. Phenylephrine stimulates the alpha-adrenergic receptors on Muller's muscle. Mullers muscle contraction is responsible for 2-3 mm of elevation of the upper eyelid. If the ptotic eyelid is not elevating after phenylephrine drops, surgeries other than Müller muscle-conjunctival resection should be considered levator resection or frontalis sling surgery).

Margin reflex distance 1 (MRD1): is the distance between the upper eyelid margin and the pupillary reflex in primary gaze. This test is used to grade the degree of ptosis. Normal MRD1 is around 4 to 4.5 mm.

Margin reflex distance 2 (MRD2): is the distance between the pupillary reflex in the center to the lower eyelid margin. It is a measure of lower lid retraction. A measurement of 5 to 5.5 mm is considered normal.

Margin reflex distance 3 (MRD3): the distance between the corneal light reflex and the center of the upper eyelid in extreme upgaze.

Margin crease distance (MCD): is the distance from the upper eyelid crease to the upper eyelid margin in downward gaze. The eyelid crease is formed by the insertion of the levator aponeurotic fibers into the upper eyelid skin. Normal MCD is 8 to 9 mm in males and 9 to 11 in females. The lid crease is absent or shallow in patients with congenital ptosis.

Palpebral aperture: is the distance between the upper eyelid and lower eyelid at the center (widest point) in primary gaze. Normal distance ranges from 7 to 10 mm in males and 8 to 12 mm in females.

Berke's method to measure levator function: Place the thumb against the brow to stop the action of the frontalis and then ask the patient to move the eyes from extreme downgaze to upgaze. Levator function is graded as

- Normal: >15mm

- Good: 12 to 14 mm

- Fair: 5 to 11 mm

- Poor: 4mm or less

Margin limbal distance MLD (also known as Putterman's method): is the distance between the center of the upper lid margin to the 6'o clock limbus in extreme upgaze. Normal MLD is around 9.0 mm.

Iliff test: is a useful test in children in the first year of life to evaluate the levator function. On everting the upper eyelid when the child looks down, if the eyelid reverts on its own, it indicates a good levator function.

Evaluation

Diagnosis of congenital ptosis is usually clinical. The following findings point towards the diagnosis of congenital ptosis:

- Mild to severe ptosis

- Reduced levator palpebrae superioris function

- Lid lag in downgaze (lid lag sign)

- Absent or weak lid crease in normal position

- Increase in size of the palpebral aperture in downgaze.

Grades of Ptosis

Ptosis may be graded based on the difference of MRD1 of both eyes in unilateral cases and difference from normal in bilateral cases as:

- Mild - 2 mm or less

- Moderate - 3 mm

- Severe - 4 mm or more

The typical case of simple congenital ptosis does not require any additional investigations for diagnosis of the condition.

Preoperative anesthetic fitness is determined in a normal fashion.

When syndromes are suspected, an appropriate clinical opinion should be obtained together with appropriate investigations to rule out other associated defects.

Treatment / Management

Surgical Correction of Ptosis Aims to Achieve the Following

- correct positioning of the eyelid as determined by the preoperative assessment.

- the symmetry of both eyelids

- minimal or no lagophthalmos

- minimal or no corneal exposure

Timing of the surgery: If there is no risk of amblyopia, it is reasonable to wait until the child is 3 to 4 years old. This will allow a better assessment of the levator function. In the presence of significant ptosis, which interferes with visual development and in the presence of bilateral ptosis, surgical correction should be undertaken promptly.

The levator function mainly decides the choice of the type of surgery required for the correction of ptosis.

A levator advancement should correct a mild degree of ptosis (1-3 mm) with good levator function (10 to 15 mm ). The Fasanella Servat procedure, where a part of the conjunctiva and the tarsal plate are resected, is less frequently used because of the destruction of normal tissues (tarsus and conjunctiva).

In cases where the levator function is very poor (<4 mm), frontalis sling surgery is the surgery of choice. The eyelids are suspended directly from the frontalis muscle with autogenous or non-autogenous materials. This procedure allows the upper eyelids to be lifted indirectly with brow elevation.[9]

Indications of frontalis surgery

- Severe ptosis with poor levator function (less than 4 mm levator function)

- Severe Marcus Gunn jaw winking syndrome

- Blepharophimosis syndrome

- Oculomotor palsy

- Traumatic levator injury with levator function less than 4 mm

Materials used to perform a frontalis sling:

- Autogenous fascia lata

- Banked fascia lata

- Silicon rods

- Mersilene mesh

- Assorted suture materials like Goretex

When the levator function is good (6 mm to 10 mm), levator resection is the treatment of choice.[9] Different routes are preferred to approach the levator muscle:

- Everbursch Approach: An anterior skin approach to the levator aponeurosis and muscle.

- Blaskovics Approach: The levator is approached via the conjunctiva.

In mechanical ptosis cases, removal or correction of the mechanical component that is depressing the upper eyelid should be performed.

Aponeurotic advancement is performed in the presence of aponeurotic dehiscence.

Marcus Gunn Jaw-Winking Syndrome

The ideal treatment for the complete elimination of the jaw-winking syndrome is bilateral excision of the levator muscle followed by bilateral frontalis suspensions. When frontalis slings are inserted without the levator muscles' extirpation, the procedure is sometimes called the "Chicken-Beard procedure."

Differential Diagnosis

Congenital ptosis should be differentiated from other acquired forms of ptosis, which include:

Neurogenic Ptosis

It can be congenital or acquired. Causes of neurogenic ptosis include innervational defects like a third nerve palsy, misdirection of the third nerve, Marcus Gunn jaw winking syndrome, Horner's syndrome, multiple sclerosis, and ophthalmoplegic migraine.

Aponeurotic Ptosis

In the presence of normal functioning LPS muscle, dehiscence in the levator aponeurosis leads to the development of aponeurotic ptosis. This is seen in age-related ptosis, ptosis after trauma or surgery, and in association with blepharochalasis.

Mechanical Ptosis

Increased weight on the upper eyelid due to multiple chalazia, eyelid edema, tumor, or dermatochalasis may result in ptosis. Other causes include scarring (cicatricial ptosis due to trachoma and ocular pemphigoid) and hematoma.

Myogenic Ptosis

Myogenic ptosis is usually acquired in origin: a disorder of the myoneural junction of the levator palpebrae superioris is seen in myasthenia gravis. Other causes include myotonic dystrophy, chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia (CPEO), oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy, ocular myopathy, and cases of trauma to the levator palpebrae superioris.

Ptosis should be differentiated from pseudoptosis (apparent drooping of the eyelid due to ocular and adnexal diseases)

The main factor differentiating ptosis from pseudoptosis is the elevation of the ptotic eyelid. On elevating the droopy eyelid, if the other eyelid droops, then it is a case of true ptosis. If the other eye remains at the same level, it is a case of pseudoptosis.

Causes of pseudoptosis:

Ipsilateral Causes

- Phthisis bulbi

- Enophthalmos

- Hypertropia

- Microphthalmia

- Dermatochalasis

- Anophthalmos

- Superior sulcus defect

- Dermatochalasis

Contralateral Causes

- Buphthalmos

- Proptosis

- Upper eyelid retraction

Prognosis

The prognosis of a patient with congenital ptosis depends upon the severity, type, associated findings, time of presentation, whether unilateral or bilateral, choice of surgery, and post-surgical outcomes. If the proper examination is done of a case of ptosis, the parameters of the measurement are very accurate. Planning of the type of surgery is precisely dependent on the preoperative measurements. If not done properly could lead to under or over correction of ptosis.

Complications

If not detected and treated on time, the severe form of congenital ptosis might lead to severe amblyopia and torticollis. The cosmetic effects of the ptosis may have a significant psychosocial impact and affect the patient's confidence and performance.

Complications of Ptosis Surgery[10]

- Postoperative swelling and ecchymosis

- Superior fornix prolapse

- Asymmetry of the eyelid height and shape in initial postoperative days.

- Lagophthalmos

- Exposure keratopathy

- Suture site granuloma

- Surgical site hematoma

- Wound infection.

- Pre-septal or orbital cellulitis.

- Drooping of the other eyelid secondary to the Herrings law of equal innervation after unilateral ptosis surgery.[11]

- Under-correction or over-correction of Ptosis (if preoperative ptosis measurement is not done accurately and best surgical treatment by the severity of ptosis and functioning of the levator muscle is not given).[12]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Parents will understandably be concerned about the outcome of surgery, the immediate postoperative care, the cosmetic outcome, and the future needs and care of children with congenital ptosis. It is vital to guide the parents and the children when they are older. We have found in our practice that as soon as children are in their early teens (and sometimes earlier), they may have questions about the cosmetic outcome of any ptosis repair. This has become more so in this age of the "selfie" and social media presence. We are therefore sharing the information we give to our patients and their parents.

Will the ptosis surgery need to be repeated?

As the child ages, it may be necessary to further advance the levator muscle if there is adequate muscle function. In the case of temporary slings performed early to improve the vision, more permanent fascia lata slings will need to be performed when the child’s legs are big enough to donate a necessary strip of fascia lata via a small incision just above the knee.

What care will I need to give my child after ptosis surgery?

Whether a direct levator advancement procedure is performed or a frontalis sling is performed, it is normal for the child to sleep with the eyelids somewhat open: this may be dramatic initially, but the degree of opening reduces over time. However, the eyelids may stay open to some degree for a long time or forever. This is normal, and every child will experience this. After surgery, the following instructions should be followed:

- The incision sites will need the application of erythromycin eye ointment three times a day for about a week: this will be prescribed.

- It will be important to keep the incision sites clean: clean hands!

- Any oral antibiotics prescribed (especially important when frontalis slings are performed) must be administered.

- For the first few weeks, applying a small amount of eye lubricating ointment (Refresh pm ointment or any other eye lubricating ointment will do) whenever the child sleeps or takes a nap is important. After a few weeks, most children do not need the continued application of ointment unless they are unwell or have a cold. We will guide you.

- Most children see so much better once the eyelid/eyelids have been lifted that you will notice them being much more physically active! This all to the good!

- If the pediatric ophthalmology team prescribed patching, please continue with the patching until you see the team again: they will reduce or stop the patching once appropriate.

- Most children can return to school within three or four days. There is very little pain after this surgery: children’s Tylenol is usually sufficient.

- We will monitor the eyelid height once every six to nine months; the pediatric ophthalmology team will assess visual development and examine you for any strabismus or need for patching.

What sort of scars will there be?

When a direct incision is made to lift the eyelid, the incision is hidden where a natural crease would form. All children heal with a pink scar initially, but this is almost invisible after a few months. After frontalis slings, the incisions become almost invisible within a few months as we make very small incisions. It is normal to feel small bumps under the skin after frontalis slings as the sling material is attached to the frontalis muscle: however, these are rarely visible.

What sort of results can we expect?

We will show you many photographs of other children with the type of ptosis of your child. It is important to understand that the photographs show the results after some months or years and that there is healing involved after surgery.

If my child has one eyelid with a very poor muscle function, should we destroy the opposite good muscle and have bilateral frontalis slings?

This is a very important question. Crowell Beard MD proposed that a normal muscle can be destroyed surgically so that the child then has bilateral droopy upper eyelids (ptosis). When bilateral frontalis slings are inserted, the lid heights will be more even, although small differences always remain. The biggest advantage is, therefore, the degree of symmetry. There is and should always be a need for serious contemplation when a normally functioning structure is destroyed in medicine and life. One is then creating a problem on the good side that did not exist before. There may be problems with the newly created droopy upper eyelid subsequently after bilateral frontalis surgery. This would, understandably, lead to regret on the part of the parents and the surgeon. Therefore, many surgeons tried to insert frontalis slings bilaterally without destroying the normal muscle. This was therefore called the "chicken Beard" procedure. It is not entirely known if this gives significantly better cosmetic results when compared to unilateral frontalis slings, and, therefore, most surgeons have abandoned this procedure. Some surgeons do not like destroying normal muscles (or any other normal anatomical structures) to create a problem where none existed before. Therefore, they insert unilateral slings with the proviso that there will be a small difference in the eyelid height between the two sides. When the child is older and can make informed consent, the surgeon can present the options to them then: it is perfectly possible to perform the Beard procedure with the destruction of the frontalis muscle and insertion of bilateral frontalis slings at any age.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Early diagnosis and timely management of ptosis help in the prevention of amblyopia and postural abnormality in children. Any child presenting with unilateral or bilateral ptosis should be evaluated thoroughly to differentiate the type of ptosis: simple congenital ptosis, congenital ptosis associated with superior rectus dysfunction, ptosis associated with blepharophimosis syndrome, and congenital synkinetic ptosis. This differentiation of the type of ptosis is necessary as the management of each entity is different.

Ideally, cases of unilateral mild to moderate ptosis without any permanent postural abnormality should be operated on at 3 to 4 years of age. By that time, the muscles are strong enough to withstand the surgical trauma, accurate measurement of ptosis is possible, and precise post-operative follow-up is possible. Cases of bilateral severe ptosis should be operated on early to avoid amblyopia and permanent chin elevation position. Parents are advised to take sequential photographs of the child at timely intervals to get an idea about the duration, severity, and progression of ptosis. By the time the child is fit for surgical correction, crutch glasses or tapes could be used to temporarily elevate the upper eyelid, although this is rarely used now.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

A patient with congenital ptosis requires assessment by an ophthalmologist but may also require to be assessed by a pediatrician, physician, cardiologist, neurologist, and head and neck surgeon. Geneticists may need to be consulted when a patient has blepharophimosis syndrome.

Interprofessional communication will lead to better patient management. The patient with congenital ptosis will most commonly present to the primary health care provider or nurse practitioner. These professionals should be aware of the condition of ptosis as it is treatable and may avoid visual problems. After prompt referral, a child with congenital ptosis should ideally be assessed by a pediatric ophthalmologist and an oculoplastic surgeon. Before and after any surgical intervention, these patients will need periodic assessment by the pediatric ophthalmologist and oculoplastic surgeon. When frontalis slings are performed using alloplastic materials, there may be slippage of the slings, necessitating further surgery. The primary care physician should receive updates on the child's progress to address any vision tests needed at school.

An interprofessional team that provides a holistic and integrated approach to postoperative care can help achieve the best possible outcomes. If the patient is to be discharged home after surgery, consultation should be made with a social worker and community nurses who can monitor the patient and make referrals as needed. Collaboration, shared decision-making, and communication are key elements for a good outcome. The interprofessional care provided to the patient must use an integrated care pathway combined with an evidence-based approach to planning and evaluation of all joint activities. The earlier signs and symptoms of a complication are identified, the better is the prognosis and outcome. Hence such a collaborative, interprofessional approach to care can ensure optimal patient outcomes. [Level 5]