Continuing Education Activity

Amebic colitis results from invasive infection of the colonic mucosa by Entamoeba histolytica (E. histolytica). Losch first reported disease due to E. histolytica in 1875; he found amoebas in colonic ulcers at autopsy and showed that the disease could be experimentally induced in vivo by rectal inoculation with human feces. Work by other scientists showed that the amoeba was the cause of the disease. E. histolytica has a worldwide distribution but uncommon in the United States, although it occurs with increased frequencies in patients with AIDS and men who have sex with other men. This activity reviews the pathophysiology, histology, diagnostic evaluation, complications, and treatment of amebic colitis. Moreover, it highlights the interprofessional team's role in educating the patients to prevent the disease and its complications.

Objectives:

Describe the pathophysiology of amebic colitis.

Explain the best methods to diagnose amebic colitis.

Explain the importance of two-step medication treatment to eliminate amebic infection completely.

Outline the importance of collaboration and coordination among the interprofessional team that can enhance patient care when encountering the extracolonic complications of amebic colitis.

Introduction

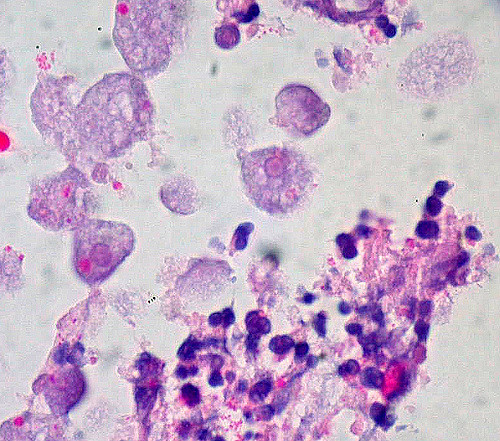

Amebic colitis results from invasive infection of the colonic mucosa by Entamoeba histolytica (E. histolytica).[1] Losch first reported disease due to E. histolytica in 1875; he found amoebas in colonic ulcers at autopsy and showed that the disease could be experimentally induced in vivo by rectal inoculation with human feces. See Image. Amebic Colitis. Work by other scientists showed that the amoeba was the cause of the disease. E. histolytica has a worldwide distribution but uncommon in the United States, although it occurs with increased frequencies in patients with AIDS and men who engage in sex with other men. Symptoms vary widely and include the following[2]:

- Dysentery with diarrhea and rectal bleeding, mimicking IBD

- Liver abscesses

- Colonic granulomatous masses that can mimic carcinoma

- Complications include colonic perforation and fistulas or liver abscesses.

E. histolytica can spread by the ingestion of the amoeba cyst. The infective cysts can occur in contaminated food and water. Transmission by fecal-oral self-inoculation can also happen in oral-anal sexual contact.[3]

Etiology

Entamoeba histolytica, the protozoan parasite causing amebiasis, colonizes the intestinal tract in 90% of susceptible individuals and presents asymptomatically. In 10%, the parasite overcomes the mucosal barrier of the colon and invades the lamina propria.[4]. Untreated invasive amebiasis can lead to severe colitis and fulminant infection, which is associated with high mortality.[5] The host acquires parasite cysts through the ingestion of contaminated food or water, mostly in areas or countries with poor sanitation.[6]

Epidemiology

Entamoeba histolytica affects approximately 10% of the global population, with over 100000 deaths/year from amebic dysentery and/or liver abscess.[5] It is most prevalent in developing countries but is known to occur in western countries, especially among recent immigrants, travelers returning from endemic areas, men who have sex with men, and immunocompromised individuals. Infection of Entamoeba histolytica parasite cysts occurs through the intake of food or water, which are contaminated by human feces because of poor environmental sanitation or personal hygiene.[7]

Pathophysiology

The gastric acid and the mucus barrier of the intestine serve as a protective mechanism that prevents the Entameba histolytica cysts from coming in contact with the intestinal epithelium. Encystation occurs in the terminal ileum or colon, which results in the trophozoites getting released into the lumen of the gut. Some individuals develop invasive amebic infection among those exposed is thought to be due to the interplay between the host's defensive factors and the virulence factor of the parasite. The three major virulence factors known to influence pathogenicity are:

- N-acetylgalactosamine-inhibitable lectin, which is responsible for binding colonic mucin and host cell adhesion.

- Amebapore which are small peptides that facilitate the killing of host cells.

- Cystine proteases; these enzymes facilitate the lysis of the host extracellular matrix.

As the pathology progresses, the colonic mucosa becomes diffusely inflamed, edematous, with associated necrosis and sometimes perforation of the intestinal wall.[8]

Histopathology

The classic endoscopic appearance is that of discrete areas of ulceration covered by exudate, with normal intervening mucosa; however, many cases depart from this description. Amebiasis may involve any part of the bowel, but it has a predilection for the cecum and ascending colon. In some cases, there is the involvement of the entire large bowel, and there may even be an extension into the terminal ileum.[9] Perforation occurs in 5% to 10% of the cases. The microscopic appearance of a rectal biopsy is rather nonspecific, although the relative paucity of inflammatory cells beneath the ulcer and the flask shape of the ulcer itself should alert the pathologist to consider this diagnosis. Confirmation rests on the identification of trophozoites of Entamoeba histolytica, which is visible in H&E slides.

Typically, the parasites measure 6 to 40 nm, are round or ovoid, and may demonstrate a surrounding halo; they contain an abundant and vacuolated cytoplasm with small nuclei and prominent nuclear membrane. In a trichrome stain, the organism's cytoplasm appears clean and free of ingested bacteria and vacuoles. Finely granular nuclear chromatin, demonstrating even distribution on the nuclear membrane, and the small central karyosome, stain a dark purple-red. Ingested RBCs are diagnostic for E. histolytica trophozoites but usually are not present. The organisms are also detectable with periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) and immunoperoxidase stains.[10]

Toxicokinetics

E. histolytica is cytotoxic to some cell types, including neutrophils, T lymphocytes, and macrophages. The organism adheres to the intestinal mucosa, invades and disrupts the mucosal barrier, produces contact-dependent killing, and stimulates apoptosis of the intestinal cells. The organism lyses and phagocytizes the cell. Cysteine proteases that destroy collagen and fibronectin mediate the invasion of the deeper layers of the intestinal wall. The host secretes proinflammatory cytokines, leading to an acute inflammatory response and migration of neutrophils and macrophages into the tissue. The organism can also secrete chemoattractants for neutrophils. It kills these cells by contact-dependent lysis, and the subsequent release of lysozymes, superoxides, and collagenases from the neutrophil granules produces additional damage to the intestinal mucosa.[6][11]

History and Physical

Almost 90% of infections are asymptomatic. Individuals who are colonized but remain asymptomatic raise a significant risk to others because they are cyst passers and, therefore, infective. Symptomatic clinical infection may appear as an acute infection in the colon called amebic colitis. Amebic colitis typically presents with symptoms of diarrhea with blood in the stools, although the symptoms can be nonspecific. When compared to bacterial colitis, amebic colitis has a more gradual onset. Amebic colitis can closely simulate ulcerative colitis or Crohn disease on clinical grounds.[12]

On physical examination, the patient may have either localized or diffuse tenderness on palpation. Rarely, a palpable mass may be present. If undiagnosed and untreated, a patient may present with toxic megacolon, which presents as an acute dilatation of the colon. This complication carries a high mortality due to associated necrosis and perforation. Fewer than 1% of patients with amebic colitis have associated extraintestinal infection, the commonest being a liver abscess. Patients with liver abscesses may have symptoms such as fever, chills, and pain in the upper right quadrant or can be asymptomatic. Weight loss, increased white blood cell counts, or elevated liver enzyme levels may be present. Jaundice is usually absent.[13] Lung abscesses may develop due to penetration of the diaphragm by amebae from hepatic abscesses or hematogenous spread. Invasion of the lung can cause symptoms such as chest pain, dyspnea, and a productive cough.[14]

Evaluation

The gold standard for diagnosing amebic colitis is the detection of trophozoites of E. histolytica with ulcers in the microscopic examination of colonoscopic biopsies or, more infrequently, in fresh stool examination. Patients with diarrhea are most likely to have trophozoites in the stool, which may be visible in direct wet mounts or trichrome-stained smears. Classically the cecum and ascending colon are affected, which show multiple punctate ulcers with intervening normal tissue. The ulcers on histological examination typically appear as flask-shaped. In severe cases of amebic colitis, the ulcers may coalesce to look similar to ulcerative colitis.[7]

Amebic liver abscesses often are detected by ultrasonographic or radiographic tests.[15] Subsequent aspiration of the abscess may reveal motile trophozoites and necrotic material composed of lysed cells. Serologic methods of detecting antibodies to E. histolytica are available; the results are positive in more than 90% of patients with the extraintestinal disease. These antibody levels rise after tissue invasion but are not protective. However, antibody tests are not particularly useful in distinguishing between past and current infection because antibodies can persist for years after an infection has resolved. Also, these tests provide limited information on patients from endemic areas. Tests that detect E. histolytica antigen in stool provide evidence of current infection. Point of care testing using immunochromatographic techniques is being developed to assist with the rapid diagnosis of E. histolytica infection.[16] Some are designed to detect the antigen in the stool and others to detect antibodies in the serum. One disadvantage of these tests is that fresh, unpreserved stool is necessary for testing.

Treatment / Management

Amebic colitis requires treatment with combination therapy, and treatment options include luminal agents combined with tissue amebicides. The luminal amebicides include iodoquinol, diloxanide furoate, and paromomycin. The tissue amebicides include nitroimidazole (metronidazole), nitazoxanide, erythromycin, and chloroquine. Surgery is required when there is an associated liver abscess that needs drainage, or the patient presents as an emergency with toxic megacolon with impending or free perforation.[17]

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses include appendicitis, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), pseudomembranous colitis, and tuberculosis. E. histolytica can rarely affect the appendix, representing an extension from an infection of the right colon. Typical IBD does not show fibrinous materials containing organisms. Ulcerative colitis characteristically shows more diffuse colonic involvement with mucosal distortion and lamina propria basal plasma cell infiltration. Crohn disease may show patchy mucosal ulceration but is distinguishable by fissure-like ulcers rather than flask-shaped ulceration; ulcers from Crohn disease are mostly horizontal, whereas the amebic ulcers grow perpendicular to the long axis of the bowel.[18][19] In colon tuberculosis, grossly, ulceration with diffuse fibrosis extends through the wall, causing stenosis and obstruction. Coexistent tuberculous peritonitis presents in rare cases. Microscopically, typical granulomas are usually present.[20]

Treatment Planning

Invasive colitis is treated with metronidazole (or alternative medications including tinidazole and nitazoxanide), followed by a luminal agent (such as paromomycin, diiodohydroxyquin) to kill intraluminal cysts. A 10-day course of metronidazole eliminates the intraluminal infection in most cases, but a second agent is still required. The recommended regimen of metronidazole for amebic colitis treatment is 500 to 750 mg three times/day in adults and 30 to 50 mg/kg per day for five to ten days in children. The alternative regimen could be 2 g oral tinidazole single dose daily in adults for 3 days, and 50 mg/kg per day oral in a single dose in children for 3 days.[21] With metronidazole alone, the parasites may persist in the intestine in as many as 40% to 60% of patients.[9] Thus, the recommendation is that patients with invasive amebiasis should receive a luminal agent as the second line to eliminate surviving cysts in the bowel lumen. Luminal medications include paromomycin, diiodohydroxyquin, and diloxanide. Current guidelines recommend either iodoquinol 650 mg orally three times a day in adults for 20 days, and 30 to 40 mg/kg per day PO in three doses in children for 20 days or paromomycin 25 to 35 mg/kg per day PO in three doses for 7 days in all ages.[22]

Toxicity and Adverse Effect Management

In patients who have known or suspected peritonitis, broad-spectrum antibacterial therapy is necessary. Surgical intervention is required in the setting of significant bowel perforation or abscesses that fail to respond to antibiotic therapy. Toxic megacolon often requires colectomy.

Prognosis

Drug treatment will cure amebiasis in a few weeks. Intestinal amebiasis can be fatal in developing countries among children, especially those younger than 5 of age. Worldwide, amebiasis is the third most common cause of death due to parasitic infection after malaria and schistosomiasis, with at least five deaths per year in the United States.[23]

Complications

Complications of amebic colitis include fulminant or necrotizing colitis, toxic megacolon, bowel perforation, peritonitis, hemorrhage, stricture formation, or obstruction.[24] Fulminant colitis occurs in 0.5% of cases, and patients present with copious dysentery, fever, leukocytosis, and vague abdominal pain; the bowel mucosa may undergo necrosis leading to transmural perforation and subsequent peritonitis. Treatment with nitroimidazole and early surgical management is required; in the cases of intestinal perforation, broad-spectrum antibiotics are the therapy of choice. Toxic megacolon, seen in approximately 0.5% of cases and associated with high mortality, usually requires surgical intervention. It appears as total or segmental non-obstructive colonic dilatation plus systemic toxicity. The amebic liver abscess has been reported to vary between 3 to 9 % of amebiasis cases.[25] Pleuropulmonary amebiasis can also occur, which is the second most frequent extra-intestinal manifestation of amebiasis after amebic liver abscess.

Deterrence and Patient Education

For travelers to endemic areas, prevention of amebic infection involves avoiding untreated water and uncooked food, such as fruit and vegetables, that may have been washed in local water. Amebic cysts are resistant to chlorine at the levels used in water supplies, but disinfection with iodine may be effective.[26] Treatment for amebiasis should include informing patients of the side effects of the medications, of the need to be adherent to the follow-up course of a luminal agent to eliminate the protozoa colonization, and of the symptoms and signs of its complications.

Pearls and Other Issues

All E. histolytica infections, even asymptomatic, should receive treatment, given the high risk of leading to invasive infection and the risk of passing the infection to the other household members.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

It is crucial to understand amebiasis pathogenesis to have enhanced treatment and prevention. The clinical team, including nurses and pharmacists, should educate the patients on the significance of handwashing and hand hygiene after defecation and before feeding. Explanations to travelers about the risks of eating raw vegetables and fruits and drinking contaminated water are recommended. The clinicians, including the doctors, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants, should be aware of treating the asymptomatic carriers to minimize the spread of infection and diminish the risk of developing invasive disease. The pharmacist should evaluate the medication choice, check for drug-drug interactions, and assist in assuring patient compliance. The clinical team and nursing staff should work together to ensure that patients are well educated regarding the risks of the disease and prevention techniques.

In summary, amebic colitis requires an interprofessional team approach, including physicians, infectious disease specialists, specialty-trained infection control and gastrointestinal nurses, and pharmacists, all collaborating across disciplines to achieve optimal patient results. [Level V]

With drug treatment, a cure is possible in most patients. However, without drug therapy, failure to thrive and even death are common. The recovery with drug treatment may take a few weeks or months.