Continuing Education Activity

Achalasia is an esophageal smooth muscle motility disorder that occurs due to a failure of relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter. This condition causes a functional obstruction at the gastroesophageal junction. This activity reviews the etiology, pathophysiology, and treatment of this condition, and highlights the need for collaboration amongst interprofessional team members to improve care coordination and in turn improve the diagnosis and treatment of this condition, leading to better outcomes for patients with achalasia.

Objectives:

- Explain the pathophysiology of achalasia.

- Outline what components go into the Eckardt symptom score and what each score means.

- Identify the best first test for achalasia with the most sensitive test for achalasia.

- Describe how collaboration amongst interprofessional team members to improve care coordination and minimize oversight, leading to earlier diagnosis and treatment and better outcomes for patients with achalasia.

Introduction

Achalasia is not a common disorder in medicine. Most clinicians will not encounter a patient with this esophageal smooth muscle motility disorder, which occurs because the lower esophageal sphincter fails to relax[1]. The esophagus also has a marked absence of peristalsis[2]. In less than 50% of patients, the lower esophageal sphincter is hypertensive.[3] This condition causes a functional obstruction at the gastroesophageal junction.

Etiology

Achalasia is thought to occur from the degeneration of the myenteric plexus and vagus nerve fibers of the lower esophageal sphincter.[2][4] There is a loss of inhibitory neurons containing vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) and nitric oxide synthase at the esophageal myenteric plexus, but in severe cases, it also involves cholinergic neurons.[5][6] The exact etiology of this degeneration is unclear though many theories have been proposed. These theories include an autoimmune phenomenon, viral infection, and genetic predisposition.[7][5] Most cases seen in the United States are primary idiopathic achalasia; however, secondary achalasia may be seen in Chagas disease caused by Trypanosoma cruzi, esophageal infiltration by gastric carcinoma, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, lymphoma, certain viral infections, and neurodegenerative disorders.[5]

Epidemiology

Achalasia is very rare, occurring with an annual incidence of roughly one per 100000 people and a prevalence of 10 per 100000.[8] It does not predominantly affect a particular age, race, or gender. However, a recent study showed increasing hospitalizations and associated costs for achalasia over the last 16 years in the United States with a disproportionate increase in patients under 65 years of age and racial minorities[8]. For some unknown reason, the incidence of achalasia increases in individuals with spinal cord injury, but these cases typically relate to damage of the cervical and thoracic vertebrae.

Altered esophageal motility similar to achalasia is also observed in individuals with anorexia nervosa. There are reports of achalasia after the use of endoscopic sclerotherapy for varices. The higher the number of sclerotherapy sessions, the greater the risk of achalasia. Most of these patients will show hypotensive peristalsis and defective lower esophageal sphincter function.

Outside the United States, rates of achalasia vary from 0.1 to 1 per every 100000 people per year. Studies show that relapse rates are higher if the initial treatment was pneumatic dilatation. However, complications have been noted to be much higher in patients who underwent a Heller myotomy compared to those who underwent pneumatic dilatation.

Achalasia occurs with equal frequency in both males and females. The disorder typically affects people between the second to the fifth decade of life with a peak incidence between the ages of 30 to 60 years.[8] Overall, less than 2% to 5% of cases occur in children less than age 16.

Pathophysiology

The esophagus is the conduit of transport for food bolus from the mouth to the stomach, but it also prevents back reflux of the contents of the stomach. Coordinated peristaltic contractions in the pharynx and esophagus pared with the relaxation of the upper and lower esophageal sphincters (LES) achieve this transport.[5] Parasympathetic excitatory and inhibitory pathways innervate the smooth muscles of the lower esophageal sphincter. Excitatory neurotransmitters, such as substance P and acetylcholine, and inhibitory neurotransmitters, such as vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) and nitric oxide (the most important inhibitory neurotransmitter of the myenteric plexus), modulate lower esophageal sphincter pressure and relaxation. Individuals with achalasia lack noncholinergic, nonadrenergic inhibitory ganglion cells, but the excitatory neurons remain unaffected.[9] This lack of inhibitory ganglion cells results in an imbalance of inhibitory and excitatory neurotransmission.[7][5] The result is a non-relaxed hypertensive esophageal sphincter.

Gradual neural degeneration directly results in excessive contractions of the lower esophageal sphincter and a loss of regulation. This degeneration leads to the functional obstruction, which then results in dilatation. This dilatation results in an irreversible aperistalsis and worsening obstructive symptoms. The reason that these changes occur is unclear.

Some studies have investigated the association of achalasia with genetic polymorphisms of the three nitric oxide synthase isoforms and specific Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) classes[9]. One European study strongly supports the notion that achalasia may be an autoimmune disorder in which autoantibodies appear to interact with DNA, like in type 1 diabetes and lupus. A genetic association study of achalasia showed that an eight-residue insertion at position 227-234 in the cytoplasmic tail of HLA-DQß1 confers the most potent known risk factor for achalasia while two amino acid substitutions in the extracellular region of HLA-DQa1 at position 41 and HLA-DQß1 at position 45 are independent risk factors for achalasia.[10] These investigators replicated this finding in another study, which also showed that the insertion was more common in southern Europeans compared to northern Europeans showing a geospatial north-south gradient among Europeans.[11]

Histopathology

Histopathological findings in advanced achalasia treated with total thoracic esophagectomy show a significant reduction in the number of myenteric ganglion cells and complete absence in some patients. Commonly seen inflammatory changes in the myenteric nerves comprise a mixture of lymphocytes, eosinophils (in all cases), and sometimes plasma and mast cells. Also, the myenteric nerves get focally or wholly replaced by collagen.[12][7]

Other extramyenteric morphological features include submucosal periductal or glandular inflammation, muscular hypertrophy with secondary degeneration and fibrosis, diffuse squamous hyperplasia, lymphocytic mucosal esophagitis or inflammation of the lamina propria and submucosa with prominent germinal centers, infiltration of the muscularis externa and propria by activated eosinophils.[7][12] Activated eosinophils cause damage to tissues by producing cytotoxic eosinophil granule proteins such as eosinophil-derived neurotoxin, eosinophilic cationic protein, and eosinophil major basic protein.[13] It is unclear if the inflammation observed is due to ongoing nerve damage or if it is a secondary phenomenon in response to achalasia.[7][12] Another study comparing histopathological changes in early versus advanced achalasia concluded that myenteric inflammation with an injury to and eventual loss of ganglion cells was the initial pathological change leading to subsequent injury and fibrosis of myenteric nerves.[14]

History and Physical

The majority of patients with achalasia typically present with dysphagia, initially with solids than to liquids though 70-97% of patients will have dysphagia to both solids and liquids at presentation.[15] Dysphagia and regurgitation are the most common presenting symptoms in achalasia. More than half of patients will present with chest pain, but an improvement of esophageal emptying rarely alleviates the pain. As the disease progresses, patients may have symptoms of regurgitation with possible aspiration, nocturnal cough, heartburn, and weight loss from difficulty eating. Weight loss is often rapid because of the inability to swallow. Less common symptoms are hiccups or difficulty belching. Symptoms of dysphagia and regurgitation respond better to the treatment of underlying achalasia. Extra-esophageal symptoms commonly encountered are structural or functional pulmonary abnormalities likely from recurrent aspiration or tracheal compression from the dilated esophagus. A "bullfrog neck" appearance can occur from severe dilatation and distortion of the cervical esophagus leading to tracheal obstruction and stridor. Specific gender distribution of symptoms is not typical though an Iranian study showed that chest pain was more common in women, while another study showed chest pain more common in patients less than 40. Variations in symptom distribution depend on the population studied.[3][5][16]

Physical examination may reveal an emaciated individual.

A frequently used grading system for achalasia is the Eckardt symptom score. It is used in the evaluation of symptoms, stages, and efficacy of achalasia treatment. It assigns the four most common symptoms of the disease (weight loss, chest pain, dysphagia, and regurgitation) a score of 0-3 based on the severity of symptoms with a maximum total score of 12. A score of 0-1 corresponds to clinical stage 0, 2-3 to stage 1, 4-6 to stage 2, and greater than 6 to stage 3. Regarding prognosis, stages 0-1 indicate disease remission, while stages 2-3 represent a failure of treatment.[15]

Evaluation

When there is clinical suspicion for achalasia, diagnostic studies to confirm the disease must take place as symptoms do not reliably diagnose achalasia. It is also crucial to exclude benign and malignant causes of lower esophageal obstruction[15].

The best initial test to diagnose achalasia is a barium esophagogram (barium swallow). The classic finding on the barium swallow is the smooth tapering of the lower esophagus to a “bird’s beak" appearance, with dilatation of the proximal esophagus and lack of peristalsis during fluoroscopy. Some cases reveal an air-fluid level and absence of intra-gastric air while in advanced disease, a sigmoid-like appearance of the esophagus may be visible. A timed barium swallow is used to access esophageal emptying. This variant of the classic barium swallow is performed by having the patient drink 236 ml of barium in the upright position and taking radiographs at one, two, and five minutes after the last swallow. The height of the barium column after five minutes, and the esophageal width are measured pre and post-treatment.[15][16]

Upper endoscopy (esophagogastroduodenoscopy - EGD) is recommended in all patients with suspected achalasia or dysphagia to exclude premalignant or malignant lesions involving the esophagus.[15] EGD has low accuracy in the diagnosis of achalasia and may be normal in the early stages of the disease. Findings in advanced cases include rosette appearance of the esophagogastric junction or an esophagus, which has become dilated, tortuous, and atonic often with retained food and saliva. The esophagus may be normal or show evidence of esophagitis due to chronic stasis. A firm resistance of the scope passing through the esophagogastric junction, especially in an older patient or one with a short duration of symptoms and significant weight loss, should raise the concern for pseudoachalasia, especially malignancy. Other useful studies in cases of pseudoachalasia are CT scan, endoscopic ultrasound (to rule out submucosal lesions), and transabdominal ultrasound.[15][16]

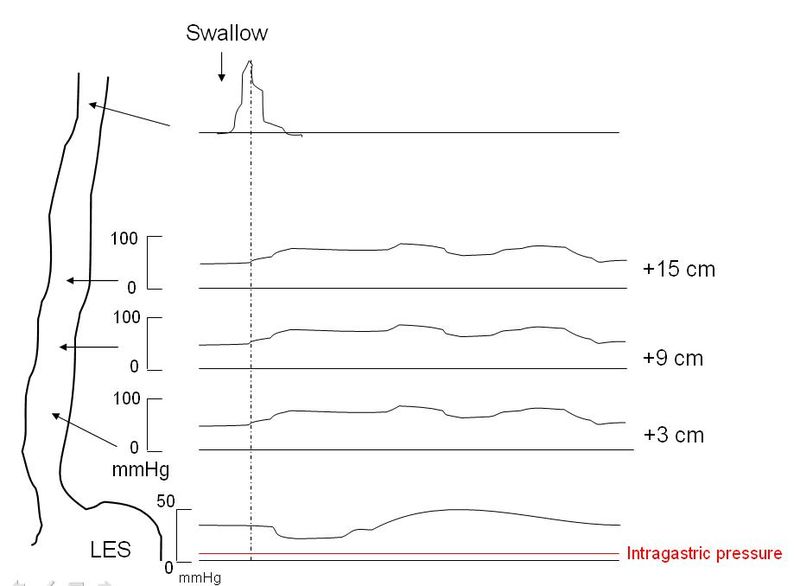

Esophageal manometry is the most sensitive test for the diagnosis of achalasia and remains the gold standard.[17] Manometry will reveal incomplete lower esophageal sphincter relaxation in response to swallowing, sometimes a lack of peristalsis in the lower esophagus, and an increase in pressure of the lower esophageal sphincter. The use of conventional manometry has mostly given way to high-resolution manometry (HRM), which also includes pressure topography plotting.[15][16][17] Using HRM, achalasia is classified by the Chicago criteria (version 3.0) into three distinct categories, which have prognostic and treatment implications. Types1-3 all show incomplete lower esophageal sphincter relaxation. The esophageal body in type 1 shows aperistalsis and no esophageal pressurization, type 2 shows aperistalsis and panesophageal pressurization in 20% or more of swallows while type 3 shows spastic (premature) contractions and distal contractility integral (DCI) over 450 mmHG-s-cm in 20% or more of swallows. The integrated relaxation pressure in type 1 is 10mmHg, type 2 achalasia 15 mmHg, and type 3 achalasia 17 mmHg. Type 2 achalasia had the best positive response to treatment, and type 3 the least favorable response to treatment. The best initial treatment option for types 1 and 2 are conservative measures such as pneumatic dilatation and surgical myotomy, while type 3 achalasia appears to respond better to initial treatment with peroral endoscopic myomectomy (POEM).[15][16][17]

Recommended Courses of Action

- Esophageal manometry to reveal incomplete lower esophageal sphincter relaxation in response to swallowing, high resting lower esophageal sphincter pressure, and the absence of esophageal peristalsis.

- Prolonged esophageal pH monitoring to rule out gastroesophageal reflux disease and determine if the treatment causes abnormal reflux

- Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) to rule out any cancer of the gastroesophageal junction or fundus

- Concomitant endoscopic ultrasonography if a tumor is suspected

Treatment / Management

Treatment is to ease the symptoms of achalasia by decreasing the outflow resistance caused by a non-relaxing and hypertensive lower esophageal sphincter. Current treatment modalities for primary idiopathic achalasia are nonsurgical or surgical. Nonsurgical options are pharmacotherapy, endoscopic botulinum toxin injection, or pneumatic dilatation. Surgical options are laparoscopic Heller myotomy (LHM) and peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM).

Pharmacologic treatments include the administration of nitrates, calcium channel blockers, and phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors to reduce the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure. Calcium channel blockers inhibit the entry of calcium into the cells blocking smooth muscle contraction, leading to a decrease in LES pressure. Hypotension, pedal edema, headache, the rapid development of tolerance, and incomplete symptom improvement are limiting factors to its use. Nitrates increase nitric oxide concentrations in smooth muscles, causing an increase in cyclic adenosine monophosphate levels, which leads to smooth muscle relaxation. These treatments are less effective, provide only short-term relief of symptoms, and are primarily reserved for patients who are waiting for or who refused more definitive therapy, such as pneumatic dilatation or surgery.[16][17]

Endoscopic injection of botulinum toxin can be used in high-risk patients or those who relapse after myotomy. Botulinum toxin, derived from Clostridium botulinum, is a potent biological neurotoxin known to block the release of acetylcholine at the level of the lower esophageal sphincter[16]. This treatment is useful in patients who may not be candidates for surgery or dilatation or alternatively, as a bridge to more definitive therapy. Limitations to botulinum toxin injections are that the effect is short-lived (lasting about 6 to 12 months), patients often require multiple treatments that are expensive and may reduce the success of subsequent surgical myotomy.[18][16][17]

Pneumatic dilatation of the esophagus via endoscopy is the most cost-effective non-surgical therapy for achalasia.[16][17] Dilatation of the esophagus is achieved by disrupting the circular fibers of the LES with air pressure using a graded dilator approach. Symptoms improve in 50%-93% of patients; however, 30% of patients have symptom recurrence at five years[19]. In some patients with symptom recurrence, repeat pneumatic dilatation on-demand will provide long-term remission. With on-demand repeat pneumatic dilatation, the long-term symptom relief is similar when compared with myotomy.[20][16][17] The failure rate with pneumatic dilation is higher with male gender, younger patients (with age less than 40), those with pulmonary complications, or failure of one or more previous pneumatic dilatations.[16] In young men, graded pneumatic dilation with a 3.0 cm balloon is more likely to fail compared to older men or women. Also, there is a higher risk of failure in this group of patients when starting with a 3.0 cm ballon.[21] The most common procedure-related complications are minor, but severe complications like esophageal perforation could occur and should be treated accordingly. Pneumatic dilatation is the first treatment option for a patient in whom surgery fails. If this also fails, the reason for the failure must be identified with imaging studies before attempting a second operation.

The recommended step for reducing pressure across the lower esophageal sphincter is surgical myotomy, which can be done laparoscopically.[22] This procedure will cut the circular muscle fibers running across the lower esophageal sphincter, leading to relaxation. LHM can potentially cause uncontrolled gastroesophageal reflux, so it typically pairs with an anti-reflux procedure such as Nissen, the posterior (Toupet), or the anterior (Dor) partial fundoplication. The anterior fundoplication is the more common choice. Laparoscopic Heller myotomy (LHM) with partial fundoplication is the surgical procedure of choice.[16][17] The important thing is that the fundoplication is partial, not complete, so as not to cause postoperative dysphagia, which is more severe with Nissen fundoplication. The clinical success rate of LHM is high (76 to 100%) at 35 months, with a low mortality rate of 0.1%. Disease progression after five years subsequently reduces the success rate.

Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) is an effective minimally invasive alternative to laparoscopic Heller myotomy to treat achalasia at limited centers.[23] Dissection of the circular fibers of the LES is achieved endoscopically, leading to relaxation of the LES; however, the risk of gastroesophageal reflux is high because it does not include an antireflux procedure. Esophagectomy is the last resort.

Differential Diagnosis

When a patient presents with dysphagia, the diagnosis of malignancy should always be in view.

Other disorders in the differential include:

- Diffuse esophageal spasm

- Scleroderma

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease

- Stricture

- Schatzki ring

- Hiatal hernia

- Paraesophageal hernia

Prognosis

The use of pneumatic dilatation and laparoscopic myotomy can produce good results with symptom relief. Rates of esophageal perforation are rare after pneumatic dilatation, but relapses are frequent.

Complications

- Esophageal perforation

- Recurrence

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease

- Bloating

- Potential cancer risk

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

All patients who undergo treatment for achalasia need long-term follow-up because all available treatments are palliative, making recurrences common. Additionally, some treatments for achalasia may also result in the development of reflux disease, which often requires treatment.

Consultations

Consultation with a thoracic surgeon and a gastroenterologist for management is essential.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Despite several years of research, the precipitating factor in the development of achalasia is unknown. Theories have speculated that a viral infection sets off an autoimmune phenomenon in a genetically susceptible host, but studies have failed to confirm this. Currently, available treatment options for achalasia do not focus on halting disease progression but rather are directed at symptom relief such as reducing dysphagia, chest pain, and regurgitation, preventing complications such as gastroesophageal reflux disease, weight loss, megaesophagus. Therefore, patients should receive counsel that achalasia is a lifelong disease so that expectations about treatment outcomes are realistic. Patients also need to understand necessary lifestyle changes following myotomy, such as the need to eat small food boluses in an upright position, which allows gravity to assist with food transit and never to lay flat but rather at 30 to 45 degrees due to increased risk for aspiration.

Pearls and Other Issues

Pneumatic dilatation and laparoscopic myotomy are effective treatments for managing achalasia. Surgery is preferred if an experienced surgeon is available.

Do not use botulinum toxin and medications if performing a pneumatic dilatation or laparoscopic Heller myotomy.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Achalasia is a rare disorder of the esophagus with no cure. All currently available treatments remain palliative. The disorder is best managed with an interprofessional team to ensure good outcomes

Coordination of care between the nutritionist, gastroenterologist, and thoracic surgeon by the primary care provider (nurse practitioner, physician assistant, or primary care physician) is essential. It is imperative that a diagnosis is made earlier by the primary care provider, especially as symptoms of reflux may be attributed to GERD for years delaying diagnosis. Most patients are managed as an outpatient, but those with dehydration, severe malnutrition, or electrolyte abnormalities may need hospitalization for stabilization and hydration. Patients with significant weight loss need nutritional supplements to prevent worsening malnutrition.

The primary care clinicians, including the nurse practitioner, should encourage lifestyle changes. Maintaining healthy body weight and sleeping with the head of the bed elevated can help drain the esophagus with gravity. The dietitian should educate the patient on foods that should not be eaten and avoiding all solid foods at bedtime. The pharmacist should educate the patient on medications that can help with achalasia, as well as verifying dosing and checking for interactions, informing the treating clinician of any concerns that arise. In addition, the patient needs to be informed that while botulinum toxin does work in some patients, it is only a temporary treatment. The surgical nurse should educate the patient on pneumatic dilatation and myotomy, as well as assisting during the procedures and monitoring the patient.

Even after successful treatment, life long follow-up of these patients is necessary as there is a small risk of malignancy. The interprofessional team should communicate with each other so that the patient receives the optimal standard of care treatment. The interprofessional team approach outlined above will drive patient outcomes positively. [Level 5]