[1]

Nieuwenhuys R. The insular cortex: a review. Progress in brain research. 2012:195():123-63. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53860-4.00007-6. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 22230626]

[2]

Uddin LQ, Nomi JS, Hébert-Seropian B, Ghaziri J, Boucher O. Structure and Function of the Human Insula. Journal of clinical neurophysiology : official publication of the American Electroencephalographic Society. 2017 Jul:34(4):300-306. doi: 10.1097/WNP.0000000000000377. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 28644199]

[3]

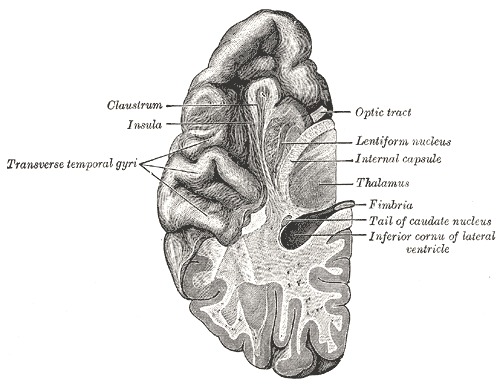

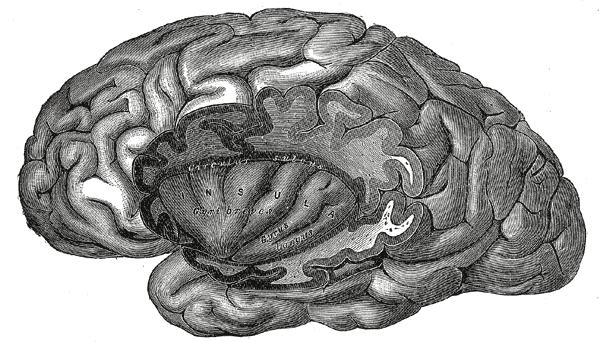

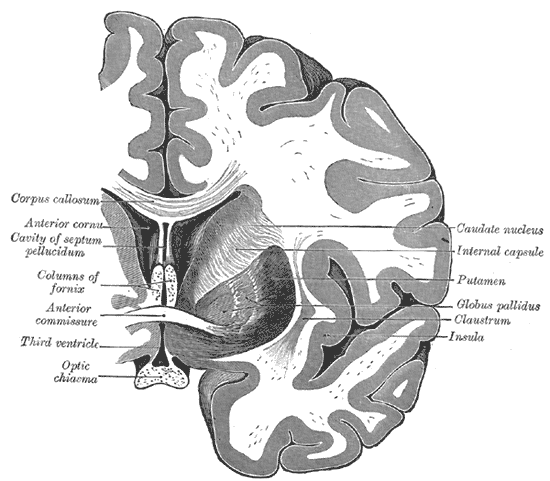

Varnavas GG, Grand W. The insular cortex: morphological and vascular anatomic characteristics. Neurosurgery. 1999 Jan:44(1):127-36; discussion 136-8

[PubMed PMID: 9894973]

[4]

Tanriover N, Rhoton AL Jr, Kawashima M, Ulm AJ, Yasuda A. Microsurgical anatomy of the insula and the sylvian fissure. Journal of neurosurgery. 2004 May:100(5):891-922

[PubMed PMID: 15137609]

[5]

Kalani MY, Kalani MA, Gwinn R, Keogh B, Tse VC. Embryological development of the human insula and its implications for the spread and resection of insular gliomas. Neurosurgical focus. 2009 Aug:27(2):E2. doi: 10.3171/2009.5.FOCUS0997. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 19645558]

[7]

Zhang Z, Hou Z, Lin X, Teng G, Meng H, Zang F, Fang F, Liu S. Development of the fetal cerebral cortex in the second trimester: assessment with 7T postmortem MR imaging. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 2013 Jul:34(7):1462-7. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3406. Epub 2013 Feb 14

[PubMed PMID: 23413246]

[8]

Williams JP, Joslyn JN. Lissencephaly: computed tomographic diagnosis. The Journal of computed tomography. 1983 May:7(2):141-4

[PubMed PMID: 6872559]

[9]

DODGSON MC. A congenital malformation of insular cortex in man, involving the claustrum and certain subcortical centers. The Journal of comparative neurology. 1955 Apr:102(2):341-64

[PubMed PMID: 14381541]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[11]

Poblete T, Jiang X, Komune N, Matsushima K, Rhoton AL Jr. Preservation of the nerves to the frontalis muscle during pterional craniotomy. Journal of neurosurgery. 2015 Jun:122(6):1274-82. doi: 10.3171/2014.10.JNS142061. Epub 2015 Apr 3

[PubMed PMID: 25839922]

[12]

Kemp WJ 3rd,Tubbs RS,Cohen-Gadol AA, The innervation of the scalp: A comprehensive review including anatomy, pathology, and neurosurgical correlates. Surgical neurology international. 2011;

[PubMed PMID: 22276233]

[13]

Wormald PJ, Alun-Jones T. Anatomy of the temporalis fascia. The Journal of laryngology and otology. 1991 Jul:105(7):522-4

[PubMed PMID: 1875131]

[14]

Przybylowski CJ, Hervey-Jumper SL, Sanai N. Surgical strategy for insular glioma. Journal of neuro-oncology. 2021 Feb:151(3):491-497. doi: 10.1007/s11060-020-03499-4. Epub 2021 Feb 21

[PubMed PMID: 33611715]

[15]

Hervey-Jumper SL, Li J, Osorio JA, Lau D, Molinaro AM, Benet A, Berger MS. Surgical assessment of the insula. Part 2: validation of the Berger-Sanai zone classification system for predicting extent of glioma resection. Journal of neurosurgery. 2016 Feb:124(2):482-8. doi: 10.3171/2015.4.JNS1521. Epub 2015 Sep 4

[PubMed PMID: 26339856]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[16]

Sanai N, Polley MY, Berger MS. Insular glioma resection: assessment of patient morbidity, survival, and tumor progression. Journal of neurosurgery. 2010 Jan:112(1):1-9. doi: 10.3171/2009.6.JNS0952. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 19612970]

[17]

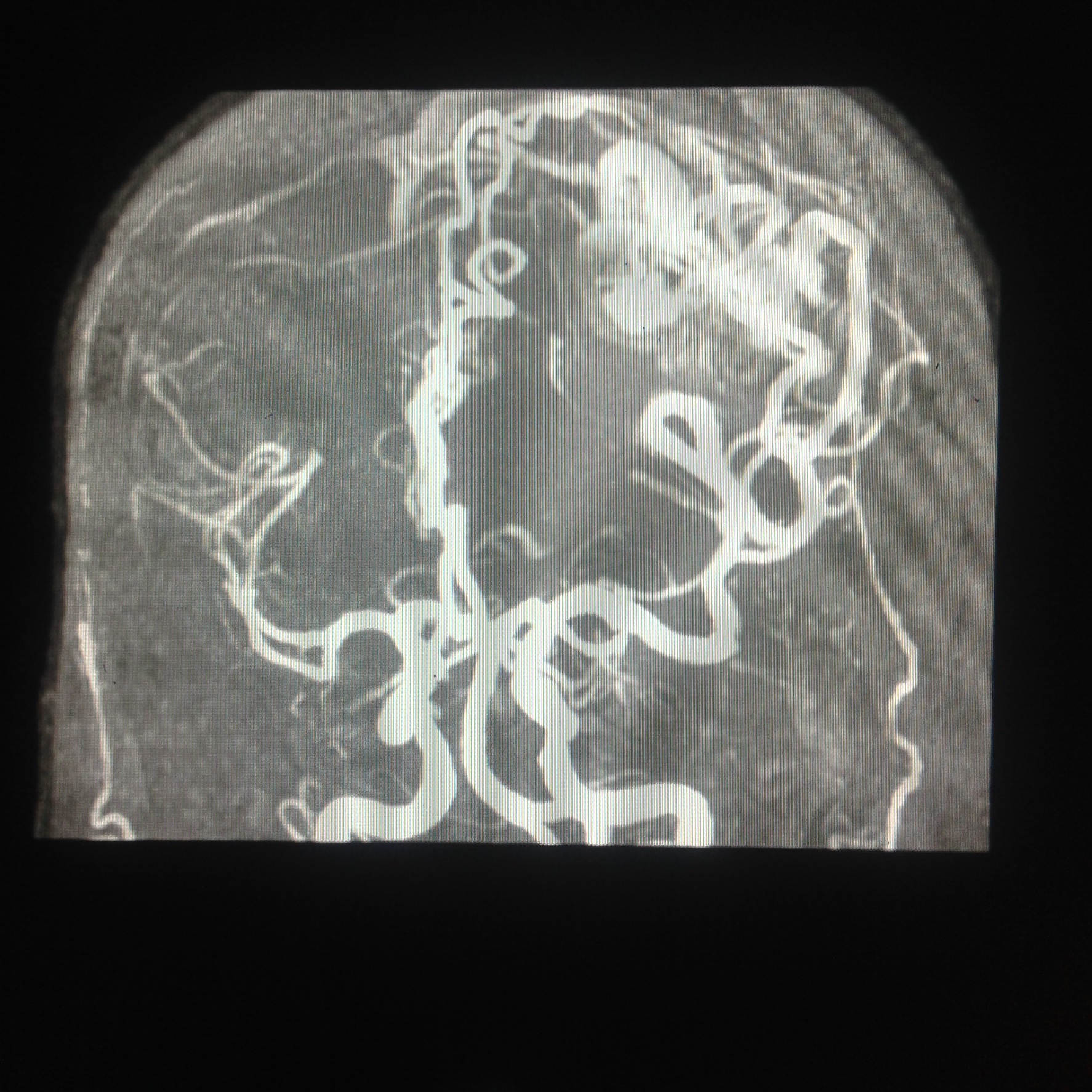

Potts MB, Chang EF, Young WL, Lawton MT, UCSF Brain AVM Study Project. Transsylvian-transinsular approaches to the insula and basal ganglia: operative techniques and results with vascular lesions. Neurosurgery. 2012 Apr:70(4):824-34; discussion 834. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e318236760d. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 21937930]

[19]

Michaud K,Duffau H, Surgery of insular and paralimbic diffuse low-grade gliomas: technical considerations. Journal of neuro-oncology. 2016 Nov;

[PubMed PMID: 27161250]

[20]

Hameed NUF, Qiu T, Zhuang D, Lu J, Yu Z, Wu S, Wu B, Zhu F, Song Y, Chen H, Wu J. Transcortical insular glioma resection: clinical outcome and predictors. Journal of neurosurgery. 2018 Oct 19:131(3):706-716. doi: 10.3171/2018.4.JNS18424. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 30485243]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[21]

Panigrahi M, Chandrasekhar YB, Vooturi S, Ram GA, Rammohan VS. Surgical Resection of Insular Gliomas and Roles of Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Diffusion Tensor Imaging Tractography-Single Surgeon Experience. World neurosurgery. 2017 Feb:98():587-593. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.11.001. Epub 2016 Nov 10

[PubMed PMID: 27838429]

[22]

Wesseling P, Capper D. WHO 2016 Classification of gliomas. Neuropathology and applied neurobiology. 2018 Feb:44(2):139-150. doi: 10.1111/nan.12432. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 28815663]

[23]

Duffau H, Capelle L. Preferential brain locations of low-grade gliomas. Cancer. 2004 Jun 15:100(12):2622-6

[PubMed PMID: 15197805]

[24]

Lu VM, Goyal A, Quinones-Hinojosa A, Chaichana KL. Updated incidence of neurological deficits following insular glioma resection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical neurology and neurosurgery. 2019 Feb:177():20-26. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2018.12.013. Epub 2018 Dec 17

[PubMed PMID: 30580067]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[25]

Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Weller M, Fisher B, Taphoorn MJ, Belanger K, Brandes AA, Marosi C, Bogdahn U, Curschmann J, Janzer RC, Ludwin SK, Gorlia T, Allgeier A, Lacombe D, Cairncross JG, Eisenhauer E, Mirimanoff RO, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Brain Tumor and Radiotherapy Groups, National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. The New England journal of medicine. 2005 Mar 10:352(10):987-96

[PubMed PMID: 15758009]

[26]

McGirt MJ,Chaichana KL,Attenello FJ,Weingart JD,Than K,Burger PC,Olivi A,Brem H,Quinoñes-Hinojosa A, Extent of surgical resection is independently associated with survival in patients with hemispheric infiltrating low-grade gliomas. Neurosurgery. 2008 Oct;

[PubMed PMID: 18981880]

[27]

Walid MS. Prognostic factors for long-term survival after glioblastoma. The Permanente journal. 2008 Fall:12(4):45-8

[PubMed PMID: 21339920]

[28]

Sugita K, Takemae T, Kobayashi S. Sylvian fissure arteriovenous malformations. Neurosurgery. 1987 Jul:21(1):7-14

[PubMed PMID: 3614608]

[30]

Chiluwal AK,Klironomos G,Dehdashti AR, Surgical Resection of a Complex Spetzler-Martin Grade IV Medial Sylvian Arteriovenous Malformation: 3-Dimensional Operative Video. Operative neurosurgery (Hagerstown, Md.). 2020 Jul 1;

[PubMed PMID: 31742361]

[31]

Pabaney AH, Reinard KA, Massie LW, Naidu PK, Mohan YS, Marin H, Malik GM. Management of perisylvian arteriovenous malformations: a retrospective institutional case series and review of the literature. Neurosurgical focus. 2014 Sep:37(3):E13. doi: 10.3171/2014.7.FOCUS14246. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 25175432]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[32]

Cereda C, Ghika J, Maeder P, Bogousslavsky J. Strokes restricted to the insular cortex. Neurology. 2002 Dec 24:59(12):1950-5

[PubMed PMID: 12499489]

[34]

Di Stefano V, De Angelis MV, Montemitro C, Russo M, Carrarini C, di Giannantonio M, Brighina F, Onofrj M, Werring DJ, Simister R. Clinical presentation of strokes confined to the insula: a systematic review of literature. Neurological sciences : official journal of the Italian Neurological Society and of the Italian Society of Clinical Neurophysiology. 2021 May:42(5):1697-1704. doi: 10.1007/s10072-021-05109-1. Epub 2021 Feb 11

[PubMed PMID: 33575921]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[36]

Isnard J, Guénot M, Sindou M, Mauguière F. Clinical manifestations of insular lobe seizures: a stereo-electroencephalographic study. Epilepsia. 2004 Sep:45(9):1079-90

[PubMed PMID: 15329073]