Continuing Education Activity

Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease involve multiple organ systems. They are common and may result in significant morbidity. This activity reviews the features of the most commonly occurring extraintestinal manifestations and highlights the interprofessional team's role in evaluating and treating patients with these conditions.

Objectives:

- Identify the extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease.

- Summarize the etiology of extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease.

- Outline the physical exam findings of extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease.

- Describe some interprofessional team strategies that can drive better patient outcomes for those with inflammatory bowel disease.

Introduction

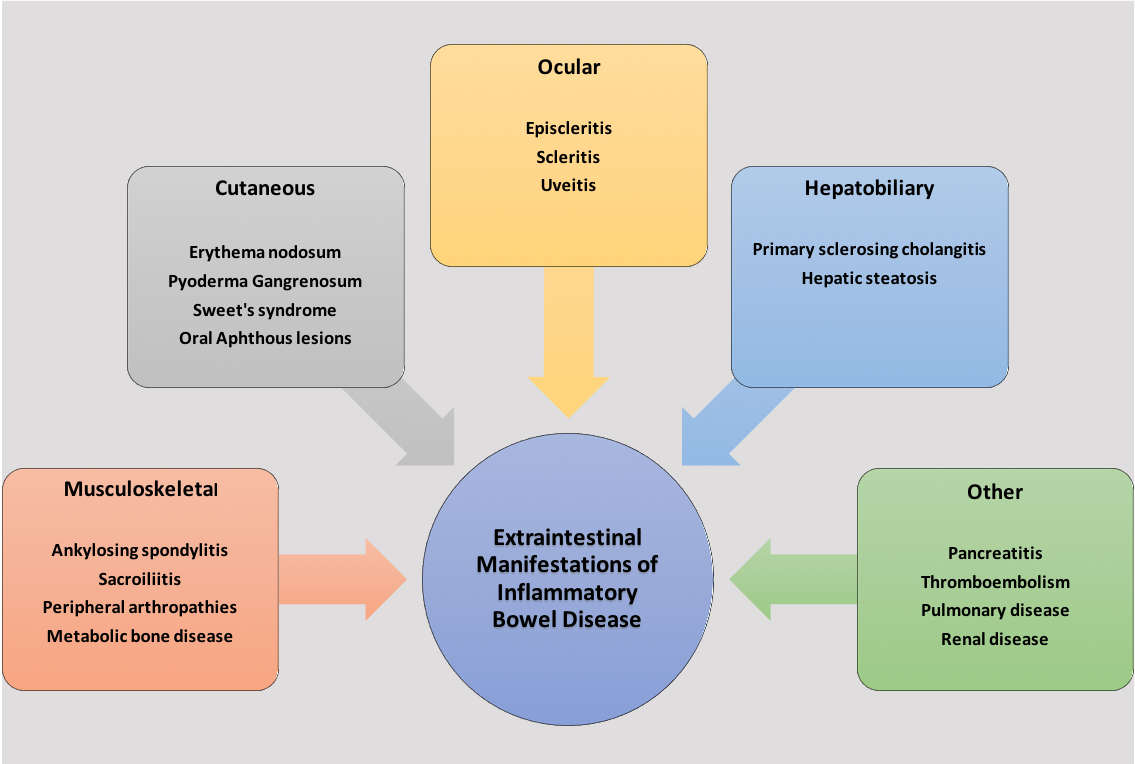

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic immune-mediated disorder comprised of Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis. Ulcerative colitis affects the large intestines, whereas Crohn disease may affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT). IBD is a multisystem condition that predominantly affects the gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, ocular, and cutaneous systems. The complications that arise outside the intestinal inflammation of IBD are known as extraintestinal manifestations (EIMs) of IBD. Regularly, these manifestations result in significant morbidity in IBD patients, even more so than the intestinal disease itself. EIMs present in 5% to 50% of all IBD patients.[1]

The severity and occurrence of EIMs and their correlation with intestinal-IBD activity vary. Most EIMs are directly associated with an ongoing intestinal flare. This includes aphthous ulcers, pauciarticular arthritis, erythema nodosum (EN), and episcleritis. Other EIMs like ankylosing spondylitis(AS) and uveitis are independent of intestinal disease activity.[2][3] Single or multiple EIMs may arise before or after the intestinal manifestations or diagnosis of IBD. Studies have revealed that the presence of a single EIM increases the likelihood of developing additional EIMs.[4]

Musculoskeletal Manifestations

Musculoskeletal manifestations are the most common IBD EIMs (arising in about 40% of IBD patients).[4] These arthropathies manifest mainly as either axial or peripheral spondyloarthritis (SpA). Peripheral SpAs are further categorized into two types. Pauciarticular (Type 1) peripheral arthritis presents as acute, asymmetrical arthritis involving six or fewer joints (mainly the large joints). It is self-limited, with episodes lasting less than 10 weeks. It correlates with intestinal-IBD activity. Hence, the treatment of IBD results in the improvement of symptoms. Polyarticular (Type 2) peripheral arthritis presents as symmetric arthritis involving the small joints. It is unrelated to IBD activity and hence may precede the IBD diagnosis. Dactylitis, enthesitis, and the above peripheral arthropathies are differentiated clinically. Axial arthropathies include AS and sacroiliitis. Ankylosing spondylitis occurs in 5 to 10% of IBD patients.[5] It presents in young adults with morning stiffness, low back pain that aggravates with rest, and spine abnormalities on imaging. It has a progressive course and is associated with HLA-B27 in affected individuals. Sacroiliitis occurs in 25% of IBD patients.[6] Axial arthropathies are less frequent than peripheral arthropathies and occur independently of intestinal-IBD activity. They arise more frequently in males as compared with females. Treatment of musculoskeletal manifestations of IBD comprises a combination of physiotherapy, corticosteroids (intraarticular/systemic), anti-inflammatory, and anti-tumor necrosis factor medication.

Cutaneous Manifestations

Cutaneous manifestations of IBD occur in up to 15% of IBD patients.[4] The most common conditions include EN, pyoderma gangrenosum, Sweet syndrome, and oral aphthous lesions. EN frequently arises as tender raised subcutaneous nodules on the lower extremities. These nodules appear red/purple, measuring 1-5 cm in size, and occurs more commonly in females than males. EN is a self-limited condition that coincides with intestinal-IBD activity and improves with IBD treatment. Specific treatment options for mild EN include leg elevation, compression stockings, analgesic, and anti-inflammatory medication.[7]

Severe disease is uncommon with IBD and should prompt investigation for infectious causes of EN. Pyoderma gangrenosum is a relatively rare manifestation seen in 0.4% to 2% of IBD patients.[8] Pyoderma gangrenosum arises at sites of trauma, a phenomenon called pathergy and follows an unpredictable and severe course. It may arise anywhere. However, the most commonly involved sites are the extensor surfaces of the lower limbs. There may be one or more lesions comprising of erythematous pustules or nodules that may rapidly spread, resulting in deep purulent ulcers. Histopathological examination of the lesion reveals a sterile culture, diffuse neutrophil infiltration with dermolysis. Since most patients with PG have underlying IBD, treatment of IBD results in the resolution of symptoms. Sweet’s syndrome, also known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, is a rare cutaneous manifestation of IBD that presents as tender, papulosquamous exanthema or nodules involving the limbs, trunk, or face.[8] It may also present with systemic signs and symptoms like fever, arthritis, leukocytosis, and conjunctivitis. It generally correlates with intestinal-IBD activity but may precede the diagnosis. Histopathological exam of the lesion reveals the presence of neutrophilic infiltrate. The condition responds effectively to topical or systemic corticosteroid treatment. Oral lesions associated with IBD commonly affect individuals with Crohn disease. These lesions arise due to oral inflammation and ulceration and correlate with intestinal disease activity. Common conditions include aphthous lesions, periodontitis, and pyostomatitis vegetans. Treatment requires adequate IBD treatment with topical steroids for oral lesions.

Ocular Manifestations

About 2% to 5% of patients with IBD present with ocular manifestations, making eyes the third most common extraintestinal tissue apart from joints and skin affected by IBD. The most common ocular manifestations include episcleritis, scleritis, and uveitis. Episcleritis presents with sensations of ocular burning, irritation, pain, and redness. Episcleritis should be differentiated from scleritis clinically as the latter is a serious condition that presents with severe ocular pain and tenderness. In severe cases, scleritis may present with visual impairment that requires urgent referral to the ophthalmologist to avoid permanent vision loss. Less severe cases benefit from topical steroid therapy, and IBD treatment as episcleritis and scleritis correlate with intestinal disease activity. In comparison, uveitis may precede IBD diagnosis and occurs independently of intestinal-IBD activity. It presents as ocular pain, photophobia, blurred vision, and headache. Slit-lamp examination reveals the presence of peri-limbic edema and inflammatory changes in the anterior chamber. Like scleritis, uveitis requires prompt treatment with topical or systemic corticosteroids to prevent complications like vision loss and evaluation by an ophthalmologist.[9]

Hepatobiliary Manifestations

IBD results in hepatobiliary manifestations in about 50% of patients during their illness.[10] These manifestations include primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), autoimmune/granulomatous hepatitis, fatty liver disease, cholestasis, gallstone formation, and autoimmune pancreatitis.[11] PSC is the most common hepatobiliary manifestation of IBD, as 75% of PSC patients are diagnosed with IBD.[12]

PSC results in inflammation and fibrosis of the intra- and extrahepatic biliary tract. It presents with RUQ pain, fever, fatigue, jaundice, itching, and weight loss. Liver function tests reveal a cholestatic pattern with magnetic resonance cholangiography revealing the presence of multiple segmental bile duct strictures and dilatations resulting in the classic ‘beads-on-a-string’ appearance. Advanced disease inevitably leads to cirrhosis, portal hypertension, and hepatic failure. PSC progresses independent of intestinal-IBD activity, and hence IBD treatment does not improve the condition. Treatment of PSC includes ursodeoxycholic acid, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with dilatation of bile ducts, or hepatic transplantation. In patients with Crohn disease, severe ileitis or ileal resection results in bile salt malabsorption that contributes to gallstone formation.

Other Manifestations

Urological manifestations of IBD include nephrolithiasis with possible urinary outflow obstruction. Nephrolithiasis is most commonly seen in patients with Crohn disease due to ileal malabsorption/ileal resection. The resulting fat malabsorption in the gut predisposes to calcium oxalate kidney stone formation. Dehydration due to diarrheal episodes in IBD patients further exacerbates renal stone formation. Patients with IBD are at an increased risk of developing thromboembolic disorders. These disorders occur independent of the intestinal disease activity and result from the IBD-related chronic systemic inflammation that leads to atherosclerosis.[13]

Most common disorders include ischemic heart disease, stroke, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism. The presence of any of the signs and symptoms of these conditions requires prompt management to prevent mortality. IBD also predisposes to metabolic bone disorders resulting in low bone mass in up to 14 to 42% of affected patients. The etiology for bone loss is multifactorial. It may be contributed primarily by the IBD pathogenesis or secondary to poor calcium absorption or side effects of IBD treatment resulting in low bone mass and fractures. IBD has also been associated with interstitial pneumonia and interstitial nephritis. However, the exact prevalence of these EIMs is unknown.

Etiology

IBD and its EIMs have a multifactorial etiology, including genetic predisposition, immune dysregulation, and intestinal microbiota dysbiosis. The resultant chronic systemic inflammation is responsible for the signs and symptoms of the disease. The pathogenesis of EIMs is believed to occur due to an abnormal immune response towards shared epitopes in the gastrointestinal mucosa and the extraintestinal sites of disease.[5]

EIMs have a genetic predisposition as individuals with siblings and first-degree relatives with IBD are more likely to manifest these symptoms.[14] IBD and its EIMs are associated with the presence of specific major histocompatibility complex loci. HLA-A2, HLA-DR1, and HLA-DQw5 are associated with EIMs in Crohn disease, whereas HLA-DR103 is associated with EIMs in ulcerative colitis.[15] Various HLA complexes are associated with specific EIMs, such as PSC and AS with HLA-B8/DR3 and HLA-B27, respectively.[16]

Some studies have proposed the pathogenesis of EIMs as an autoimmune reaction towards a tropomyosin isoform expressed in the non-pigmented ciliary epithelium (eye), keratinocytes (skin), chondrocytes (joint), the biliary epithelium (hepatobiliary tract), and the gastrointestinal epithelium (GIT).[17][18] Alteration of the normal intestinal flora has resulted in the pathogenesis of intestinal inflammation seen in IBD in animal studies; however, its role in humans is still unclear.[19]

Epidemiology

EIMs are seen in 5% to 50% of the IBD patients during their lifetime.[1] EIMS occurs in 31% of patients suffering from Crohn disease and 43% of patients with ulcerative colitis and is more prevalent among females (50%) than males (34%). The frequency of EIMs overall is lower among the pediatric population compared with the adults. During a lifetime, one EIM is seen in 63% of the patients, whereas two EIM are reported in 27% of the IBD patients. Among all the EIMs, arthritis is the most common, followed by oral aphthous ulcers and uveitis.[20]

History and Physical

IBD patients presenting to the clinic require a thorough evaluation for signs and symptoms of EIMs. Common presenting complaints include abdominal pain and bloating, diarrhea/constipation, fever, fatigue, weight loss, tenesmus, inflammation of joints, skin, eyes, and liver. A thorough family history of IBD is essential as having a family member with IBD increases the likelihood of having the disease.

Evaluation

A careful evaluation may allow timely diagnosis and management of IBD and its EIMs. It requires a thorough history and physical examination followed by appropriate laboratory tests and diagnostic imaging/procedures. Commonly used laboratory tests include stool studies and blood tests. Diagnostic and imaging procedures include X-ray, computed tomography scan, magnetic resonance imaging, capsule endoscopy, flexible colonoscopy, and sigmoidoscopy.

Treatment / Management

Treatment of EIMs of IBD requires a multidisciplinary approach and comprises medical treatment and lifestyle modifications. IBD treatment generally results in the resolution of the EIMs that are associated with intestinal-IBD activity. The first step in the management of mild IBD is to reduce inflammation via anti-inflammatory drugs. These include corticosteroids and aminosalicylates. Immunosuppressant drugs are used for moderate disease activity unresponsive to anti-inflammatory medication. These include methotrexate, azathioprine, and mercaptopurine that suppress the immune system and help resolve the inflammatory response towards the different tissues affected in IBD. Severe IBD requires treatment with newer drug treatments called biological agents such as anti-tumor necrosis factor agents. Antibiotics like metronidazole and ciprofloxacin are used for the treatment of secondary infectious complications of IBD. Vitamin supplements, anti-diarrheal medication, and analgesics are prescribed for symptomatic relief of symptoms.

EIMs independent of IBD activity require specific treatment to improve quality of life and reduce morbidity and mortality. Musculoskeletal EIMs of IBD are treated with a combination of physiotherapy, analgesic, and anti-inflammatory medication such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and systemic corticosteroids. Cutaneous manifestations like pyoderma gangrenosum require topical corticosteroid therapy with wound care. Ocular manifestations, including scleritis and uveitis, require treatment with topical corticosteroids. Currently, there is no treatment available for the resolution of PSC. Hence patients with progressive disease course eventually require hepatic transplantation.

Lifestyle modifications like smoking cessation, physical activity, adequate hydration, stress management, and avoiding dairy products improve IBD symptoms. Patients are encouraged to join IBD support groups and seek a therapist as IBD is a chronic disease having long-term physical and mental effects. Routine colonoscopy surveillance is done due to the risk of colon carcinoma associated with IBD.

Differential Diagnosis

EIMs of IBD should be differentiated from extraintestinal complications that result secondarily due to chronic disease and malnutrition or treatment side effects. Musculoskeletal manifestations of IBD are the most common EIMs. However, side effects from intestinal IBD treatment may mimic these EIMs, including corticosteroid treatment leading to osteonecrosis and anti-tumor necrosis factor treatment leading to lupus arthropathy. It is also important to exclude differentials for IBD like celiac disease, lactose intolerance, peptic ulcer disease, irritable bowel syndrome, traveler’s diarrhea, gastroenteritis, and colon carcinoma as they may present with similar features.

Prognosis

IBD has a waxing and waning course, and most patients maintain an active, healthy lifestyle. Treatment and lifestyle modifications help manage the symptoms of the disease. Careful screening and early management of EIMs improve health, quality of life and reduce morbidity. EIMs associated with intestinal-IBD disease activity manifest during flare-ups of the disease, whereas EIMs independent of intestinal-IBD severity may precede IBD diagnosis or occur during IBD remission.

Complications

IBD is a complicated disease having widespread complications. Chronic malabsorption and blood loss lead to iron deficiency anemia and vitamin deficiency anemias. The chronic inflammation within the intestine may lead to strictures and fistulas that occur more commonly with Crohn disease. Perianal fistulas are most common. However, entero-enteric, entero-cutaneous, entero-vesical, or entero-vaginal fistulas may also occur. Ulcerative colitis predisposes to the risk of toxic megacolon, colonic perforation, and colonic carcinoma. PSC is a progressive disease that eventually leads to cirrhosis and hepatic failure if left untreated. Chronic inflammation-induced hypercoagulable state predisposes to deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Chronic inflammation, malnutrition, and treatment therapies may lead to osteopenia, osteoporosis, growth failure, amyloidosis, and fatty liver disease.

Deterrence and Patient Education

EIMs of IBD should be differentiated from extraintestinal complications resulting from chronic inflammation associated with IBD resulting in nutritional deficiencies, osteopenia, osteoporosis, renal and gall stones, peripheral neuropathies, and IBD drug-associated side effects. Caution should be exercised when using Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in managing intestinal-IBD-related EIMs as they have been associated with IBD exacerbation.[21]

As IBD increases the risk for bone loss and hypocalcemia, Primary care providers must counsel patients regarding the benefits of smoking cessation, physical activity, calcium, and vitamin D supplementation in their diet. IBD patients may be susceptible to thromboembolic events during prolong periods of immobility such as long-haul flights and need to take necessary precautions, including adequate hydration, smoking cessation, regular physical activity, and use of compression stockings.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

IBD is a complex disease with widespread systemic manifestations that can present as a challenge to healthcare professionals. As such, it requires the efforts of an interprofessional healthcare team comprised of clinicians (including PAs and NPs), specialists, nursing staff, and pharmacists. When these various disciplines coordinate their activities, exercise open communication, and function as a cohesive interprofessional team, patient outcomes will benefit. [Level 5]

Several EIMs do not respond to intestinal-IBD treatment and hence require close monitoring and management to avoid complications. Musculoskeletal manifestations of IBD, including axial arthropathies, require frequent monitoring and coordinated management by gastroenterologists and rheumatologists. Regardless of being an ulcer, pyoderma gangrenosum has been known to worsen following surgical debridement due to pathergy. It is imperative to rule out pyoderma gangrenosum as the cause of an ulcer in IBD patients before proceeding. Additionally, pyoderma gangrenosum may require topical treatment by a dermatologist.

Patients diagnosed with PSC should be referred for colonoscopy and monitored under colonoscopic surveillance programs to exclude the presence of underlying IBD as both conditions increase the likelihood of the development of colonic dysplasia/carcinoma. Colonoscopy should be performed whenever PSC is diagnosed and repeated at 1 to 2 years interval in patients with IBD.[22] Due to the systemic nature of IBD, it is essential to recognize, evaluate and treat EIMs of IBD promptly to reduce morbidity.