Continuing Education Activity

Paragangliomas are rare neuroendocrine tumors arising from extra-adrenal paraganglia. While akin to pheochromocytomas, they manifest diverse symptoms contingent on their location. Typically found along the sympathetic chain, they often secrete catecholamines, causing hypertension and tachycardia. Parasympathetic variants, located along cranial nerves, are usually non-secretory. Though mostly benign, malignancy can occur, underscoring the importance of early detection and treatment.

This activity explores paragangliomas, covering etiology, pathophysiology, evaluation, and management. It delves into genetic and environmental factors influencing development and offers guidance on diagnostics, including genetic testing and imaging. The activity highlights advancements in surgical and radiation therapies, stressing the importance of a multidisciplinary approach for optimal patient outcomes in managing this complex condition.

Objectives:

Identify the clinical manifestations and imaging characteristics associated with paragangliomas.

Select appropriate diagnostic modalities for confirming the diagnosis of paraganglioma.

Apply evidence-based guidelines for managing paragangliomas, including implementing timely and appropriate surgical interventions.

Collaborate with all interprofessional team members to provide efficient, comprehensive, and coordinated care for patients with paragangliomas.

Introduction

Paraganglia are groups of neural crest-derived neuroendocrine cells classified as adrenal or extra-adrenal. Paragangliomas, rare and highly vascular tumors, originate from sympathetic or parasympathetic extra-adrenal autonomic paraganglia. Some refer to them as extra-adrenal pheochromocytomas, while others might designate a pheochromocytoma as an intra-adrenal paraganglioma.

About 86% of paragangliomas located outside of the head and neck are sympathetic, secreting norepinephrine, unlike the more differentiated intraabdominal adrenal medulla tumors neuroblastoma and pheochromocytoma which primarily secrete epinephrine.[1] Associated symptoms are episodic hypertension, tachycardia, headache, and diaphoresis.

Sympathetic paragangliomas arise anywhere along the sympathetic chain, from the skull base to the bladder and prostate. Most commonly, they occur at the vena cava and the left renal vein junction or the aortic bifurcation near the take-off of the inferior mesenteric artery known as the organ of Zuckerkandl.

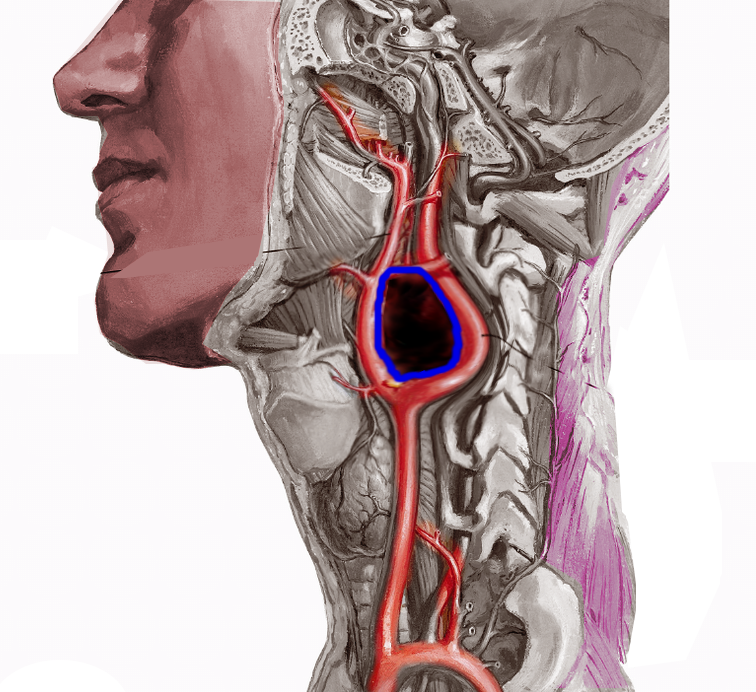

Tumors originating from parasympathetic origin are usually asymptomatic and inactive, predominantly located in the neck and skull base along the distribution of the vagus and glossopharyngeal nerves. Most parasympathetic paragangliomas arise from the carotid body (see Image. Carotid Artery Tumor), but some originate from the jugulotympanic and vagal paraganglia. Rarely one originates from the laryngeal paraganglia.

Only about 5% of tumors in the neck and skull base secrete catecholamines. Jugulotympanic paragangliomas and carotid body paragangliomas comprise approximately 80% of the paragangliomas in the head and neck.

Paragangliomas commonly present as a single, benign, unilateral tumor, but 1% of sporadic and 20% to 80% of familial cases may have multiple tumors.[2] Instances of malignancy and metastasis are rare. Early identification leading to complete surgical resection is often curative and carries a favorable prognosis. Detecting distant metastases is the only reliable way to assess the biological aggressiveness of paragangliomas.

Paragangliomas are primarily sporadic, although 30% to 50% of cases are familial. Some familial forms may be associated with genetic syndromes, such as variations in the genes encoding different subunits of the succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) enzyme, Carney-Stratakis dyad, neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), von Hippel-Lindau (VHL), and multiple endocrine neoplasia types 2A and 2B (MEN2).[3] A surgical biopsy performed during resection is the gold standard for confirming the diagnosis. However, it does not distinguish between pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Typically, clinical correlation suffices for diagnosis, aided by imaging and pathological findings of the lesion.

Etiology

Paraganglia are chromaffin neurosecretory cells originating from neural crest cells. Sympathetic paraganglia involve the adrenal medulla, the paravertebral sympathetic chains, and nerves that innervate retroperitoneal and pelvic organs. Parasympathetic paraganglia are situated along the cervicothoracic branches of the glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves. The parasympathetic ganglia include:

- Jugulotympanic

- Orbital

- Vagal

- Laryngeal

- Subclavian

- Carotid and aortic bodies

Paragangliomas are tumors originating from the paraganglia. Researchers and clinicians refer to parasympathetic paragangliomas as nonchromaffin paragangliomas, contrasting them with chromaffin paragangliomas arising from chromaffin cells within the sympathetic paraganglia and the adrenal medulla.[4]

While usually sporadic, they may also present as part of familial syndromes. Children are more likely to have paraganglioma in the presence of a familial syndrome. Most hereditary variants, especially involving the skull base and neck, are due to variations in the genes encoding different subunits of the SDH enzyme complex. Patients with MEN2, NF1, VHL, and Carney-Stratakis dyad are also at increased risk of developing intra- and extra-adrenal paragangliomas. The associated genetic variations are as follows:

- The SDH complex plays a central role in energy metabolism, functioning as an enzyme of the tricarboxylic acid cycle and as complex II of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. The SDHx genes, including SDHA, SDHB, SDHC, and SDHD, collectively encode the 4 subunits (A, B, C, and D) of SDH. Pathogenic mutations in SDHx lead to 5 autosomal dominant hereditary paraganglioma syndromes. Additionally, SDHAF2 encodes a protein required for the flavination of the SDHA subunit, representing the fifth mutation. The most common mutation occurs in SDHD.

- MEN2A manifests with thyroid cancer, pheochromocytoma or paraganglioma, and primary parathyroid hyperplasia. Medullary thyroid cancer, pheochromocytoma, or paraganglioma, but not hyperparathyroidism, characterize MEN2B. The underlying genetic cause is an inherited variant in RET, a proto-oncogene.

- NF1 manifests as café au lait spots, peripheral neurofibromas, neurocognitive abnormalities, central nervous system tumors, soft tissue sarcomas, and other tumors, including pheochromocytoma or paragangliomas. Neurofibromatosis results from a pathogenic variation in the tumor suppressor gene NF1.

- Benign and malignant tumors, including hemangioblastomas of the cerebellum and spine, retinal angiomas, clear cell renal cell cancers, pheochromocytomas/paragangliomas, and neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas, characterize VHL disease. Pathogenic variants in the tumor suppressor VHL gene are the underlying cause.

- Carney-Stratakis dyad is an autosomal dominant disorder with incomplete penetrance, characterized by gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) and paragangliomas. Many cases are due to germline pathogenic variants of SDHB, SDHC, or SDHD. Carney-Stratakis triad, including pulmonary chondroma, does not have a genetic link.

- SDHB gene pathogenic variants can be associated with living at high altitudes.

- Cyanotic congenital heart disease may cause gain-of-function pathogenic variants of EPAS1, which encodes for hypoxia-inducible factor-2α.

- Families affected by familial pheochromocytoma may experience loss of function pathogenic variants in the MAX (MYC-associated factor X) gene.

In addition to genetic predispositions, factors such as hypoxia from residing at high altitudes or having cyanotic congenital heart disease and chronic obstructive lung disease elevate the risk of carotid body paragangliomas. Recent data indicates that hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) may play a role in the genesis of paragangliomas in specific cases. These transcription factors activated by hypoxia trigger genes that facilitate adaptation and survival in low-oxygen conditions, thereby regulating energy, iron metabolism, and erythropoiesis. Hypoxia prompts increased intracellular levels of HIFs.

Individuals with variants in the VHL and SDHx genes exhibit a pseudohypoxic response, leading to the stabilization, dysregulation, and overexpression of HIFs. Tumors with pathogenic variants in the VHL gene closely resemble those with variants in the SDHx genes. Shared characteristics of both VHL and SDHx variants include angiogenesis, hypoxia, and a diminished oxidative response, suggesting a common molecular pathway in the development of these tumors. Tumors associated with RET, NF1, TMEM127, or MAX pathogenic variants (the RET/NF1 cluster) display a signature of genes involved in translation initiation, protein synthesis, and kinase signaling.

The nomenclature of paragangliomas typically reflects their location. In the ear, the collective name is jugulotympanic paraganglioma, after the jugular bulb paraganglia and the tympanic paraganglia. These tumors were previously referred to as glomus jugulare and glomus tympanicum. Carotid body tumosr are situated at the carotid bifurcation (see Image. Carotid Body Tumor).

Jugulotympanic paragangliomas predominantly affect women in their fifties, with only 10% to 16% being bilateral. While most jugulotympanic paragangliomas are sporadic, around 10% exhibit an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. Those with autosomal dominance tend to manifest earlier and occur equally between men and women. A linkage with abnormalities in chromosome 11 has been identified in patients with familial types of jugulotympanic paraganglioma.

Epidemiology

Paragangliomas are related to pheochromocytomas and are often grouped together, contributing to some uncertainty regarding their precise incidence. In the US, medical professionals diagnose approximately 500 to 1000 paragangliomas annually. The combined incidence of paragangliomas and pheochromocytomas is 0.7 to 1.0 per 100,000 person-years.[5]

Most patients with sporadic paraganglioma present between their 30s and 50s, with the mean age of diagnosis being 47.[5] Tumors located in the skull base and neck tend to occur in older patients. In contrast, abdominal tumors are more likely to present in patients at a younger age, around 36, compared to 43 for those with tumors in the skull base and neck.[5] Patients with hereditary paragangliomas usually present about 10 years earlier than those with sporadic disease, often in their early 30s.

Most paragangliomas are benign. The incidence of malignant paragangliomas is around 90 to 95 cases per 400 million person-years. Among patients with hereditary paraganglioma, the male-to-female ratio is approximately equal. In contrast, sporadic tumors are much more prevalent in females, with a female-to-male ratio of 3 to 1.

Pathophysiology

The primary pathophysiology underlying a paraganglioma involves either the excessive secretion of catecholamines or bony erosion due to mass effect. These catecholamines include dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine. Norepinephrine is primarily engaged in extra-adrenal paragangliomas. Paragangliomas cause episodic secretion of catecholamines, leading to symptoms of catecholamine excess.

The sympathetic nervous system receptors, collectively referred to as adrenergic receptors because they bind and release norepinephrine, include α1, α2, β1, and β2. Epinephrine and norepinephrine stimulate these receptors within the sympathetic nervous system. Stimulation of these receptors results in:

- α1: Contracts smooth muscle and stimulates the central nervous system, causing vasoconstriction to nonessential organs. The result is the contraction of the sphincters of the gastrointestinal (GI) system with diminished motility and peristalsis. The bladder sphincter and uterus contract, pupils dilate, and the liver undergoes gluconeogenesis.

- α2: Stimulation of α2 receptors results in vasodilation.

- β1: Increases the contractility of the heart and the heart rate along with renin release from the kidney.

- β2: Primarily relaxes smooth muscle and dilates blood vessels, causing bronchodilation in the lungs, decreased gastrointestinal motility, gluconeogenesis, and relaxation of the uterus.

Parasympathetic paragangliomas located in the skull base are usually non-secretory, with less than 5% secreting catecholamines and becoming symptomatic. These non-secretory paragangliomas often manifest with symptoms related to their mass effect on surrounding structures rather than catecholamine excess.

Histopathology

Histologically, paragangliomas and pheochromocytomas are nearly identical, differing primarily in the presence of chromaffin cells. On a cellular level, sympathetic and parasympathetic paraganglioma are indistinguishable.[4] The gross specimen is firm, rubbery, and brown, with a central scar and a thin capsule. Microscopically, polygonal or round epithelioid cell nests grow in a trabecular pattern known as the Zellballen pattern. The nuclei of the chief cells, which contain neurosecretory vesicles, are centrally located with finely clumped chromatin and eosinophilic, visible granular cytoplasm.

Sympathetic cells may exhibit hyaline globules on the hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain, and giant mitochondria with paracrystalline inclusions may be observable on electron microscopy. Furthermore, characteristics such as nuclear atypia, pleomorphism, necrosis, mitotic figures, and local or vascular invasion are typical findings but do not indicate malignancy. Distant metastasis remains the primary indicator of malignancy.[6]

To differentiate paragangliomas from other similar appearing tumors, clinicians use immunohistochemical staining to reveal strong positivity for neuron-specific enolase, synaptophysin, and chromogranin. Conversely, staining for keratins is usually negative.

History and Physical

Paragangliomas typically represent benign hypervascular tumors that grow slowly. Symptoms are dependent on the tumor location. The most common presentations of all paragangliomas are mass effect and catecholamine excess. The remaining tumors may be asymptomatic, discovered incidentally on radiographic imaging or during screening of known carriers of pathogenic variants.

Other possible clinical signs include upper GI bleeding, back or chest pain, cough, dyspnea, exercise-induced nausea, and vomiting. Examination usually reveals signs of sympathetic overload or mass effect, including but not limited to vocal cord paralysis causing hoarseness, cranial nerve paralysis, restlessness, tachycardia, diaphoresis, uncontrolled episodic hypertension, perspiration, cold and clammy skin, dilated eyes, dry mouth, and sometimes piloerection. Bradycardia and syncope may occur due to carotid sinus syndrome. Hemoptysis, dysphagia, or chest pain may be present in superior venous sinus syndrome.

Catecholamine Excess

The most common feature of catecholamine excess is hypertension, with episodes that can be continuous or intermittent and often paroxysmal. These episodes commonly present with the classic associated symptoms of headache, palpitations, and profuse sweating, known as "the classic triad."[7] If all 3 elements of the "classic triad" are present simultaneously, a healthcare professional can diagnose a catecholamine-secreting tumor with 90% specificity. However, the likelihood of all 3 symptoms presenting simultaneously is approximately 40% and highly unlikely if the tumor originates in the skull base or neck.

Patients experiencing intermittent episodes of hypertension along with other classic symptoms, particularly when triggered by factors such as postural change, anxiety, medications, exercise, or maneuvers that increase intra-abdominal pressure, highly suggest a catecholamine paraganglioma. Rarely, patients with an SDHB-related mutation may secrete dopamine, causing normal blood pressure or hypotension.

The constellation of hypertension, hematuria, and symptoms of catecholamine excess with micturition or sexual activity are classic signs of a bladder paraganglioma. Syncope with micturition is a hallmark sign of a bladder paraganglioma. Additional symptoms of catecholamine excess are dry mouth, facial flushing, dilated pupils, fidgetiness, constipation, fatigue, tremors, panic-like symptoms, and generalized weakness due to exhaustion. Patients may also present with orthostatic hypotension due to low plasma volume, papilledema, blurry vision, lightheadedness, weight loss, polyphagia, polydipsia, mood disturbances, hyperglycemia, and weight loss.[8]

Head and Neck Paragangliomas

Paragangliomas located in the head and neck region typically present as small tumors. Their smaller size often contributes to a relatively higher rate of successful surgical resection and favorable outcomes than larger tumors in other locations.

Carotid body tumors

- Typically painless

- Gradually enlarge

- The upper part of the neck below the angle of the jaw

- Rubbery nontender mass in the lateral neck

- Positive Fontaine's sign

- More freely movable in the horizontal plane than vertically

- The presence of a carotid bruit or the mass may be pulsatile (see Image. Shamlin Grade 3 Carotid Body Tumor)

As the tumor size increases, patients may develop dysphagia, deficits of cranial nerves VII, IX, X, XI, and XII, hoarseness, or Horner syndrome.

Jugulotympanic paragangliomas

- Slow-growing

- Usually present with pulsatile tinnitus with or without conductive hearing loss

- Facial nerve paralysis

- Vertigo

- Hoarseness

- Paralysis of lower cranial nerves

- Bluish pulsating mass behind the tympanic membrane.

Vagal paragangliomas

- Most common site is the inferior nodose ganglion

- Variable symptoms based on location

- Dizziness

- Blurred vision

- Facial droop

- Dysphagia

- Neck mass

- Pain

- Cranial nerve deficits

- Horner syndrome

Rarely, a cervical paraganglioma can originate near or in the thyroid gland or dura. Tumors within the dura cause symptoms of neurologic compression consistent with the tumor location.

Evaluation

Evaluation of catecholamine-secreting tumors involves comprehensive biochemical testing, imaging studies, and genetic testing to determine hereditary predispositions and guide appropriate management strategies. Additionally, functional studies like 24-hour urine collection for metanephrines and catecholamines, plasma-free metanephrines, and clonidine suppression tests may be conducted to assess hormonal secretion patterns and aid in diagnosis.

Blood and Urine Tests

The initial step in diagnosing a pheochromocytoma or a paraganglioma involves evaluating patients for the excess production of catecholamines, followed by anatomical identification of the tumor. Regardless of symptoms, all patients with suspected paraganglioma should undergo evaluation for excess catecholamines.

The evaluation typically begins with measuring urinary or plasma fractionated metanephrines, as the transformation of catecholamines into metanephrines within the tumor persists regardless of the tumor's secretion of catecholamines.[9] A test for 24-hour urine catecholamines and metanephrines is beneficial in diagnosing. Medications such as tricyclic antidepressants, serotonin reuptake inhibitors, norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, antipsychotics, and levodopa can result in a false-positive test. Therefore, discontinuing potentially interfering medications at least 2 weeks before testing is necessary to ensure accurate results

Stressful clinical conditions like an acute illness can also contribute to false-positive test results.[7] Paragangliomas are unlikely to secrete epinephrine, and a 24-hour urine collection for norepinephrine and fractionated metanephrines is more sensitive for paragangliomas than a 24-hour collection for epinephrine. However, an exception exists for patients with MEN2-related pheochromocytoma or paragangliomas, who almost always secrete epinephrine. While measuring plasma catecholamine is less sensitive, values 2 times the upper limit of normal can also support the diagnostic process.[7]

Radiological Tests

After confirming catecholamine excess, contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scanning or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen and pelvis are the imaging tests of choice. Nonionic contrast is necessary for CT scanning to prevent triggering a catecholamine crisis. An alpha blockade must be administered before scanning if ionic contrast is necessary unless catecholamine excess has been ruled out.

A CT showing 10 Hounsfield units or less suggests a lipid-rich mass, ruling out pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. In cases where CT or MRI cannot localize the tumor, the next step is cross-sectional imaging of the head, neck, thorax, and radioisotope or functional imaging.

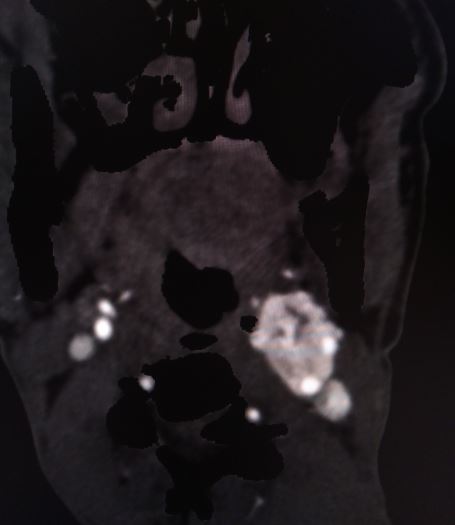

CT scan and MRI findings consistent with a paraganglioma typically include intense contrast enhancement and possibly a salt-and-pepper appearance. The "salt" appearance reflects hemorrhage, while the "pepper" appearance is due to flow voids representing high vascularity.

Radioisotope imaging

Metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) is structurally similar to norepinephrine. An MIBG scan using iobenguane I-123 can be valuable in detecting tumors not evident on CT or MRI or identifying multiple tumors when CT or MRI results are positive. However, MIBG scans have limitations, including a high false-positive rate compared to the rate with pheochromocytoma, and the potential for the isotope to concentrate in the salivary glands, obscuring skull base and neck paragangliomas. Administration of potassium iodide drops is necessary when using I-123 to prevent thyroid radiotracer uptake.

Conventional positron emission tomography (PET) demonstrates high sensitivity in detecting paragangliomas. Integrating positron-emitting radiolabeled somatostatin analogs in high-resolution PET with CT can enhance detection and staging accuracy. Gallium labeled 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid or Ga 68 DOTATOC (68Ga-dotatate–labeled PET-CT), 18F-fludeoxyglucose (FDG), or 18F-Fluoro-L-dihydroxyphenylalanine (18F-DOPA PET) scans are extremely sensitive in identifying any hidden pheochromocytoma or paraganglioma. While 68Ga-dotatate–labeled PET-CT offers superior accuracy in tumor localization, its availability is limited.[10] Indium-111 pentetreotide (OctreoScan) remains another imaging option, although positron-emitting radiolabeled somatostatin analogs are preferred due to their enhanced spatial resolution when available.

Mass Effect

The initial evaluation of neck and skull base tumors begins with an ultrasound, CT, or MRI. Ultrasound imaging often reveals a hypervascular, solid, well-defined, hypoechoic tumor. In carotid tumors, ultrasound may display a splaying of the carotid bifurcation. The classic CT scan findings associated with a paraganglioma include:

- Homogeneous mass with unenhanced Hounsfield units in the 40 to 50 range

- Intense enhancement following administration of intravenous contrast and delayed washout

- Cystic changes, necrosis, and internal calcifications

Patients with suspected jugulotympanic paragangliomas should undergo CT scanning to assess any potential destruction of the temporal bone. CT is particularly effective for evaluating bone destruction, but MRI is superior for delineating adjacent vascular and skull base structures. Common MRI observations indicative of a paraganglioma include:

- T1-weighted images: Paragangliomas typically exhibit a tumor matrix displaying intermediate signal density with dispersed regions of the signal void, indicative of high-flow blood vessels.

- T-2 weighted images: Often demonstrate a pronounced hypervascular pattern, characterized by a "salt and pepper" appearance.

While these MRI findings are not exclusive to paragangliomas, they become valuable when considered collectively alongside the patient's medical history, physical examination, and the tumor's location. This comprehensive approach aids in accurate diagnosis and facilitates appropriate treatment planning for patients with suspected paragangliomas.

Genetic Tests

All patients with a paraganglioma should undergo genetic testing.[7] Standard testing evaluates for pathologic variants in RET, VHL, NF-1, SDHD, SDHC, SDHB, SDHA, SDHAF2, TMEM127, and MAX. Targeted testing can be considered if the patient presents with an apparent paraganglioma-related syndrome. Genetic testing plays a crucial role in preventing recurrence and guiding long-term observation. In cases where a genetic variant is identified, it is essential to notify and recommend testing for all first-degree relatives. Patients who are known carriers should undergo the following testing:

- All SDHx pathogenic variant carriers

- Annual screening with plasma or 24-hour urine collection for fractionated metanephrines

- All SDHB, SDHC, and at-risk SDHD or SDHAF2 carriers

- CT or MRI of the skull base, neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis every 2 to 3 years

- I-123 MIBG scintigraphy or 68Ga-dotatate–labeled PET-CT every 5 years.

Surgical Biopsy

Lesional biopsy is the gold standard for confirming the diagnosis of paragangliomas, although it does not differentiate between pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Fine needle aspiration (FNA) is of minimal use in establishing the diagnosis due to factors such as hemorrhage, determining the tumor from other similar tumors, and the potential for causing fibrosis at the biopsy site.

Given the high vascularity of paragangliomas and the risk of catecholamine crisis, biopsy and resection are typically performed simultaneously. Preresection biopsies should be avoided unless there is no biochemical evidence of catecholamine secretion or the patient undergoes α-adrenergic blockade. If vascular anatomy requires evaluation before surgery, subtraction angiography is preferred for studying vascularity.

Approximately 20% of extra-adrenal paragangliomas are malignant, while 10% of pheochromocytomas are malignant. Nearly all paragangliomas in the head and neck are benign. Unfortunately, no combination of clinical, histopathologic, or biochemical features can reliably predict biologic behavior. Clinicians gain minimal prognostic information, risk of recurrence, or metastases from pathologic evaluations alone. Tumor deposits in tissues that do not normally contain chromaffin cells are the only confirmation of malignancy.

Patients with the SDHB genetic variant, who typically present with secretory abdominal tumors, have the highest rate of malignancy. Thus, they warrant further evaluation for metastatic disease. Radioisotope scanning using MIBG scanning, 111-In pentetreotide (OctreoScan, Mallinckrodt Medical), and PET scanning help provide full-body scans when evaluating for concurrent tumors or metastases. The preferred tests are 68Ga-dotatate–labeled PET-CT and FDG-PET.

Treatment / Management

Surgical resection remains the first-line treatment for paraganglioma and pheochromocytoma. However, in cases where definitive resection is not feasible or if a subtotal resection occurs, radiotherapy may be necessary. Controlling blood pressure before surgery and preventing intraoperative hypertensive crises may be crucial considerations, mainly based on tumor behavior.[7]

Differential Diagnosis

The following list encompasses possible differential diagnoses based on symptom characteristics:[4]

- Endocrine

- Pheochromocytoma

- Thyrotoxicosis

- Insulinoma

- Hypoglycemia

- Medullary thyroid carcinoma

- Cardiovascular

- Labile essential hypertension

- Positional orthostatic hypotension

- Carcinoid syndrome

- Pulmonary edema

- Syncope

- Orthostatic hypotension

- Cardiac arrhythmia

- Angina

- Renovascular disease

- Psychological

- Hyperventilation

- Vancomycin infusion reaction

- Anxiety and panic attacks

- Factitious disorder

- Somatization disorder

- Pharmacologic

- Sympathomimetic drug ingestion

- Recreational drug ingestion (cocaine, phencyclidine [PCP], lysergic acid diethylamide [LSD])

- Chlorpropamide-alcohol flush

- Withdrawal of adrenergic inhibitor

- Monoamine oxidase inhibitor treatment combined with a decongestant

- Neurologic

- Autonomic neuropathy

- Migraine

- Cerebrovascular accident

- Autonomic seizures

- Other

- Mast cell disease

- Recurrent idiopathic anaphylaxis

Surgical Oncology

Observation is acceptable for small, asymptomatic, non-secreting head and neck paragangliomas measuring less than 1 cm in managing paragangliomas. Many paragangliomas exhibit an indolent course with an average growth rate of approximately 1 mm per year and a doubling time of roughly 4 years.[11] Follow-up with an initial contrast-enhanced MRI or CT at 6 months is recommended, with repeat scans annually if the tumor remains stable. Tumors located outside the head and neck region are generally not observed. Therapeutic intervention may be necessary for tumors that, despite their small size, require treatment. These tumors include:

- Tympanic paragangliomas

- Jugular paragangliomas with troublesome conductive hearing loss, pulsatile tinnitus, or impending or actual facial nerve weakness

- Significant brainstem compression

- Secretory tumors

- Cranial nerve dysfunction related to tumor burden

- Clinical evidence of rapid growth

- Malignant disease

- Patient choice

Surgical Oncology

The surgical approach to these tumors depends mainly on the location, size, and body habitus of the patient. Catecholamine-secreting tumors are particularly challenging and require more extensive preoperative preparation compared with non-secreting tumors.

Preoperative Management

In patients with catecholamine-secreting paragangliomas, preoperative preparation is necessary to prevent hypertensive crisis, malignant arrhythmias, and multiorgan failure intraoperatively. Clinicians typically initiate antihypertensive medications at least 7 days before surgery to achieve low-normal blood pressure, especially in patients with catecholamine-secreting tumors.[7] Pharmacological management includes either nonselective α-adrenergic blockade with phenoxybenzamine or selective blockade with doxazosin titrated to target blood pressure.

Preoperatively, a high sodium diet and increased intake of fluids are necessary to reverse catecholamine-induced blood volume contraction, thereby preventing severe hypotension after tumor removal.[7] The β-adrenergic blockade is also required to control the heart rate, but only after establishing a sufficient α-adrenergic blockade.

While the lack of randomized evidence has raised questions about preoperative treatment, observational studies have failed to detect a difference in perioperative complications between patients without preoperative alpha blockade.[12] Nevertheless, preoperative blockade remains the recommendation for all patients with catecholamine-secreting tumors.[13]

Some centers incorporate the use of preoperative metyrosine, a catecholamine synthesis inhibitor, in addition to phenoxybenzamine. Currently, its use is primarily recommended when other agents have been ineffective or in the presence of a significant tumor burden that needs to be destroyed or manipulated during surgery.

Preoperative Embolization

Preoperative embolization may be appropriate for specific catecholamine-secreting head and neck paragangliomas, although there is no consensus regarding its use. Patients and clinicians must carefully evaluate the risks and benefits. The risk of severe adverse effects associated with embolization is low, with a risk of up to 13%. Some clinicians consider tumor size, with tumors larger than 3 cm typically being candidates for embolization, while others base the decision on the disease stage.

The advantages of embolization include reduced blood loss, shorter operative time, and easier resection. Case series have shown a 60% reduction in blood loss compared to patients who did not receive embolization and a substantial decrease in operative time.[13] However, potential complications of this approach include cerebrovascular accidents, blindness, cranial neuropathies, and even death.

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy is reserved for patients with small, non-secretory, benign tumors in the skull base and neck when removal would involve damage to critical vascular or nerve structures. It is also considered appropriate for patients with jugular paragangliomas and more advanced tympanic paragangliomas unless they are symptomatic from catecholamine secretion or tumor bulk. Radiation therapy is also helpful with recurrent tumors after surgical resection.

Intraoperative Management

Intraoperatively, catecholamine release can result in hemodynamic instability with large fluctuations in blood pressure and heart rate. Patients at risk include those with large tumors, total intravenous anesthesia, use of preoperative β-blockers, and the type of α-blocker used.[14]

Maintaining a stable heart rate, blood pressure, and urine output is crucial during surgery. An arterial line provides continuous hemodynamic monitoring. A pulmonary artery catheter may be necessary for patients with diminished cardiac output. Although large-bore peripheral IV access is also sufficient, vasoactive drugs can be administered through central venous access.

Immediate attention is required for significant changes in blood pressure, whether hyper- or hypotension. Hypertension during surgery may necessitate the administration of vasoactive compounds such as nicardipine, nitroprusside, or labetalol, while hypotension may be addressed with intravenous fluids, phenylephrine, norepinephrine, or vasopressin.

Surgical Techniques and Outcomes

Minimally invasive endoscopic surgery, such as laparoscopic and retroperitoneoscopic approaches, is typically the first consideration for patients with paragangliomas of the abdomen. This approach is also suitable for tumors in the pelvic viscera.[7][15][16] It offers advantages such as shorter operative times, fewer intraoperative complications, and shorter hospital stays.[7][17] Rates of conversion to open surgery are typically less than 1%.[17] However, resection of paragangliomas in the thorax usually requires an open approach. Radical cystectomy or partial cystectomy is necessary for bladder paragangliomas, as a transurethral approach would result in recurrence, given that a paraganglioma is not a mucosal tumor.

Paragangliomas of the head and neck present particular challenges, requiring a multidisciplinary approach. Precise imaging to determine the tumor burden is crucial.[7] The most common location is the carotid body. Larger tumors may cause cranial neuropathies. Surgeons use a transcervical approach when resecting a carotid body tumor.

In patients with vagus nerve paragangliomas, sacrificing the affected vagal nerve is likely during surgery. Tympanoplasty to resect the tumor is the preferred treatment for tympanic paragangliomas. Resection of jugular paragangliomas poses significant challenges, often requiring an infratemporal or juxtacondylar approach. The following are indications for surgical resection of jugular paragangliomas based on recommendations from the British Skull Base Society:[18]

- Ear canal bleeding or persistent discharge

- Troublesome pulsatile tinnitus

- Conductive hearing loss

- Arteriovenous shunting

- Secreting tumors

- Significant brainstem compression

- Malignant disease

- Failure of radiation therapy to control growth

The most significant risks of resection are bleeding, stroke, and cranial nerve dysfunction. Various tumor classification systems, such as the Fisch or Glasscock-Jackson classification, aid in assessing resectability and guiding surgical planning.[19]

Local recurrence rates following surgery are 6.5% at 5 years, 16.1% at 10 years, and 17.1% at 15 years.[20][21] For jugular paragangliomas, the recurrence rate is 14% at 7 years following gross total resections and 31% at 6 years following subtotal resections.[22] The likelihood of recurrence rates varies depending on the completeness of resection, with subtotal resection sometimes chosen to mitigate long-term morbidity. Factors such as tumor size, familial genetic mutation, and younger age at diagnosis are independently associated with an increased risk of recurrence.[23]

Management of Pregnant Patients

Managing pregnant patients with catecholamine-secreting paragangliomas poses unique challenges due to contraindications for nuclear imaging, risks associated with fetal and maternal surgery, and concerns regarding uteroplacental insufficiency and preoperative α-adrenergic blockade.[7] In such cases, patients may opt to delay resection until the second trimester or choose medical management during pregnancy followed by surgical resection after delivery, particularly if diagnosed in the third trimester.[7]

Complications

Postoperative complications following surgical resection of paragangliomas vary depending on the location of the tumor. Resection of paragangliomas in the head and neck risk cranial nerve deficits, including facial nerve palsy, hearing loss, hoarseness, and other lower cranial nerve damage.[24][25] Additionally, surgery in this area may result in cerebrovascular accidents.

Retrospective studies have reported new lower cranial nerve deficits postoperatively in approximately 20% of cases.[24] Cerebral spinal fluid leakage develops in 13% of cases, and 8% develop an intracranial infection.[26] Abdominal or pelvic tumor resections can lead to complications such as adhesions causing bowel obstruction, bowel perforation, peritonitis, pseudo-obstruction, adrenal insufficiency following bilateral adrenalectomy, hypoglycemia, renal failure, and heart failure.[27] Thoracic paraganglioma resections may result in pneumothorax, chylothorax, esophageal perforation, cerebrovascular accidents, uncontrollable bleeding, and cardiac tamponade.[28]

Radiation Oncology

Paragangliomas that are unresectable or recurrent may be considered for radiation therapy. While the head and neck are the most commonly treated areas, tumors originating in the thorax, abdomen, or pelvis may also be eligible for this approach. Although randomized evidence comparing radiotherapy to surgical resection is lacking, meta-analysis suggests that local control rates are comparable with acceptable toxicity.[29] Radiation therapy can be delivered through various methods, including stereotactic radiosurgery, stereotactic body radiotherapy, or conventionally fractionated radiation.

Definitive Radiotherapy

Definitive radiation is the most common use of radiotherapy in this setting, with the majority of data coming from the treatment of head and neck paragangliomas. Typically, treatment involves delivering conventionally fractionated radiation over several weeks, with a target dose ranging from 45 to 54 Gy (1.8-2.0 Gy per fraction). This approach is beneficial for substantial tumors or where dose constraints for organs at risk cannot be met with more hypofractionated courses.

Stereotactic body radiotherapy dosing ranges from 25 to 30 Gy delivered in 5 fractions or 21 Gy in 3 fractions.[30] Stereotactic radiosurgery dosing is usually 12 to 18 Gy administered in a single fraction.[30] While dedicated stereotactic radiosurgery systems such as gamma knife or CyberKnife (Accuray Incorporated) are available options, linear accelerator (LINAC) stereotactic radiosurgery and stereotactic body radiotherapy are also widely used.[31]

A study spanning 35 years and involving 104 patients treated with conventional radiotherapy for head and neck paragangliomas reported a 10-year local control rate of 94%.[32] Local control rates for stereotactic radiosurgery and stereotactic body radiotherapy range from 90% to 100%, with most follow-up imaging revealing stable or regressed tumor size. Comparisons of stereotactic radiosurgery and conventional radiation do not demonstrate a difference in local control and toxicity.[30]

While no prospective randomized trials compare surgery to definitive stereotactic radiosurgery for paragangliomas of the head and neck, a meta-analysis of 374 patients reveals a local recurrence rate of 2.1% for stereotactic radiosurgery versus 3.1% for surgery.[29] Although the local control rates are comparable, the complication rates appear to be higher with surgery than with stereotactic radiosurgery (29.6% versus 7.6%).[33]

Posttreatment tumor response is slow, with only 32% of patients showing regression after radiation treatment.[34] In contrast, 59% exhibit radiographically evident but stable disease, while 9% experience progression.[34] Among patients with pretreatment neurological dysfunction, 59% report improvement, while 32% report stabilization.[34]

Postoperative Radiotherapy

Subtotal resection may result in poorer local control rates than gross total resections in patients who opt for definitive surgery. Local control after subtotal resection is approximately 69% compared to 86% with gross total resection.[22] However, postoperative radiotherapy can improve local control rates without requiring additional surgery.

Recurrent Disease

Patients experiencing recurrent disease after surgical resection may consider radiotherapy or repeat resection. A retrospective review of recurrent head and neck paragangliomas treated with radiotherapy or surgery demonstrated 5-year freedom from 100% and 62% progression, respectively.[35] These patients may be treated with various techniques, including intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) 45 to 54Gy or SRS 13 to 16Gy.[35] Other case series have shown local control rates ranging from 83% to 100% treated with conventionally fractionated radiation therapy.[35][36][37] Complications are minimal compared with surgical resection, making radiotherapy a viable alternative in patients with extensive tumors where additional surgery would be morbid and technically challenging.

Target Delineation

A CT simulation is the first step in treatment planning, with a slice thickness of no more than 2 mm.[30] The patient lies supine, and the head is immobilized with a thermoplastic mask attached to the treatment table. MRI fusion involves contrast-enhanced T1 weighted MRI imaging, with a slice thickness no greater than 2 mm, integrating information from different sensors into a single image, which is crucial for accurate target identification.[30] When planning stereotactic body radiotherapy or conventional radiotherapy, contouring of gross tumor volume occurs with the aid of MRI, including a 2 to 5 mm expansion to produce the planning target volume. Clinicians typically apply a 0 to 1 mm margin of expansion to produce the planning target volume for stereotactic radiosurgery. In LINAC-based stereotactic radiosurgery, the dose is generally prescribed to the 80% isodose line, while on gamma knife systems, the prescribed dose is to the 50% isodose line. Elective nodal coverage is unnecessary, given the benign nature of these tumors.

Dose Constraints

The American Association of Physicists in Medicine (AAPM) Task Group 101 has well-established dose constraints for stereotactic radiosurgery and stereotactic body radiotherapy treatments.[38] Dose constraints are determined for conventionally fractionated radiation therapy using Quantitative Analysis of Normal Tissue Effects in the Clinic (QUANTEC) guidelines.[39]

Complications

Toxicity associated with single-fraction or multi-fraction radiotherapy includes nausea, vomiting, vertigo, headache, tinnitus, and cranial neuropathies. Typically, these complications are transient. The rate of neurological compromise due to treatment is approximately 8.5%, but only 2.1% of patients experienced permanent neurological sequelae.[30] Severe toxicities such as osteoradionecrosis, auditory canal stenosis, trismus, and brain radionecrosis are extremely rare.[30]

Staging

There is no formal staging system for paragangliomas, but various classification schemes are available to determine operability, particularly in the head and neck. The Glasscock-Jackson and Fisch classification schemes are below:[40]

Glasscock-Kackson Classification Scheme

- Type 1: Small tumor involving the jugular bulb, middle ear, and mastoid process

- Type 2: Extending under internal auditory canal; may have intracranial extension

- Type 3: Extending into petrous apex; may have intracranial extension

- Type 4: Extending beyond petrous apex into clivus or infratemporal fossa; may have intracranial extension

Fisch Classification Scheme

- Class A: Tumors that arise along the tympanic plexus on the cochlear promontory

- Class B: Tumors with invasion of hypotympanum; cortical bone over jugular bulb intact

- Class C1: Tumors with encroachment of the carotid foramen but no invasion of the carotid artery

- Class C2: Tumors with destruction of the vertical carotid canal

- Class C3: Tumors that invade the horizontal portion of the carotid canal but do not reach the foramen lacerum

- Class C4: Tumors with growth to foramen lacerum and along the carotid artery and the cavernous sinus

- ClassDe1/2: Tumors with intracranial but only extradural extension; De1/2 according to displacement of dura (De1 = less than 2 cm, De2 = more than 2 cm)

- ClassDi1/2/3: Tumors with intracranial and intradural extension; Di1/2/3 according to depth of invasion into posterior cranial fossa (Di1 = less than 2 cm, Di2 = between 2 and 4 cm, Di3 = more than 4 cm

Prognosis

Complete resection of benign paraganglioma carries a recurrence likelihood of less than 10%, and they do not impact overall survival. The primary concern for individuals with benign head and neck paraganglioma is preserving their quality of life. Patients undergoing surgical resection with intact neurological function have a notable risk of surgical morbidity linked to lower cranial nerve deficits, particularly when compared to individuals who already have deficits and have adapted over time.

Without subsequent radiation therapy, continued growth is probable following a subtotal resection. Vigilant surveillance becomes crucial as larger tumors heighten the risk of neural injury. Patients with multiple tumors, genetic variations, or metastatic disease face the highest risk of recurrence. A significant portion, 65%, of individuals initially presenting with metastatic disease will experience recurrent metastatic disease. Those with metastatic disease exhibit a five-year survival rate ranging between 34% and 60%, with recurrence typically occurring around 5.5 years. Notably, 31% of individuals initially diagnosed with suspected benign disease may encounter recurrence, manifesting even 50 years after the initial diagnosis. Consequently, annual lifelong surveillance is imperative.

Complications

Paragangliomas are rare tumors that arise from the extra-adrenal chromaffin cells of the sympathetic nervous system. While they are generally considered to be slow-growing and nonmetastatic, they can cause complications due to the excessive release of catecholamines (such as adrenaline and noradrenaline). The complications associated with paragangliomas include:[41][42][43]

- Hypertension: The release of excess catecholamines can lead to episodes of severe hypertension, which may be intermittent or sustained. Managing blood pressure is crucial in these cases.

- Cardiovascular complications: Prolonged high blood pressure can contribute to various cardiovascular issues, including heart attacks, heart failure, and arrhythmias.

- Catecholamine crisis: In some cases, paragangliomas can undergo sudden and significant releases of catecholamines, leading to a life-threatening condition known as a catecholamine crisis. This can result in severe hypertension, palpitations, headaches, sweating, and even organ failure.

- Orthostatic hypotension: The tumors can also affect the autonomic nervous system, leading to orthostatic hypotension. This condition causes a sudden drop in blood pressure when standing up, resulting in dizziness or fainting.

- Myocardial infarction: The increased workload on the heart due to persistent hypertension can contribute to the development of myocardial infarction.

- Neurological symptoms: Depending on the location and size of the tumor, patients may experience neurological symptoms such as headaches, visual disturbances, or other signs of nervous system involvement.

- Metastasis: While paragangliomas are often benign, they can become malignant and metastasize to other parts of the body. Malignant paragangliomas are associated with a poorer prognosis and can spread to distant organs.

- Endocrine dysfunction: Paragangliomas can affect the normal functioning of adjacent organs or glands, leading to endocrine dysfunction. For example, tumors near the adrenal glands may affect adrenal function.

- Renal complications: Prolonged hypertension can contribute to renal (kidney) damage over time, potentially leading to chronic kidney disease.

Management of paragangliomas typically involves a multidisciplinary approach, including surgery, radiation therapy, and medical management to control blood pressure and symptoms associated with catecholamine release. Regular monitoring and follow-up are essential to manage potential complications effectively. Individuals with paragangliomas must work closely with a medical team to address their specific case and individual health needs.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Rehabilitation care after surgery may be required, and the specifics depend on the tumor location and postsurgical deficits. Since the majority of patients undergo endoscopic tumor resection, the need for postoperative rehabilitation care is minimal, leading to a shorter stay in the facility.

Following surgery for catecholamine-secreting paragangliomas, patients undergo biochemical screening and imaging within 3 months. Establishing an operative cure requires normalized urinary fractionated metanephrines, catecholamines, or plasma fractionated metanephrines, and negative imaging. Radiographic imaging of the primary site, typically MRI, is performed 3 to 4 months postresection.

Head and neck paragangliomas with subtotal resection undergo a baseline MRI 8 to 12 weeks after surgery, followed by annual imaging for at least 3 years. Subsequent imaging should be every other year for 6 years and then every 3 years. For secretory tumors, monitoring includes a history and physical examination, blood pressure checks, and biochemical marker assessments every 6 to 12 months for the first 3 years postresection, followed by life-long annual biochemical testing and imaging as clinically indicated. Patients with 18-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-avid disease on preoperative PET scans undergo posttreatment surveillance through serial PET scans.

Patients with nonfunctioning paragangliomas undergo annual biochemical studies and imaging initially, with a decrease in testing frequency over time but continuing life-long. Those with nonsecretory tumors and a genetic predisposition syndrome should continue with annual plasma fractionated metanephrines. Rising levels trigger radiographic imaging of the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis to assess for new developments.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas are rare tumors originating from nerve tissue, with pheochromocytomas forming in the adrenal gland and extra-adrenal paragangliomas developing outside the adrenal gland. Extra-adrenal paragangliomas, though mostly benign, can be malignant. These tumors occur along various nerves and blood vessels in the neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis. Some secrete catecholamines, causing symptoms like headache, hypertension, palpitations, and excessive sweating. Symptoms may occur spontaneously or in response to physical or emotional stress like childbirth, an injury, anesthesia, or surgery.

Genetic conditions, including MEN 2A and 2B, NF1, Carney-Stratakis dyad, and pathogenic variants in SDH genes, increase the risk of paraganglioma. All patients who develop a paraganglioma should undergo genetic testing. Identifying genetic risk factors prompts notification of first-degree relatives for timely intervention.

Diagnosis begins by measuring catecholamine levels, followed by imaging studies like CT, MRI, or radionucleotide scans. Treatment varies based on tumor location and symptoms. Options are close observation, surgical removal, and radiation therapy. Removal of catecholamine-secreting tumors is standard. Without removal, patients are at risk for the consequences of dangerously high blood pressure, like stroke, arrhythmia, and heart attack. However, complete removal may be challenging due to the tumors' vascular nature and proximity to nerves. Patients who undergo surgical removal may require a high-salt diet, increased fluid intake, and certain blood pressure medications before surgery to prevent severe hypertension during surgery and hypotension after surgery. Genetic testing is crucial for all patients with paraganglioma, and lifelong surveillance with blood or urine tests and imaging is necessary, tailored to tumor type and location.

Pearls and Other Issues

Key points to keep in mind about paraganglioma include the following:

- Paragangliomas are rare neuroendocrine tumors arising from extra-adrenal chromaffin cells.

- Paragangliomas are uncommon. They can occur sporadically or be associated with genetic syndromes such as MEN2 and NF1.

- Patients may present with symptoms related to catecholamine excess (eg, hypertension, palpitations, diaphoresis) or mass effect symptoms depending on the tumor location.

- The classic triad of symptoms includes headache, palpitations, and diaphoresis.

- Diagnosis involves biochemical testing to detect catecholamine excess, followed by imaging modalities such as CT, MRI, or functional imaging to localize the tumor. Genetic testing is essential for identifying hereditary forms and guiding management.

- Treatment options include surgical resection, radiation therapy, and medical management to control symptoms and prevent complications.

- Preoperative α-blockade is essential to prevent intraoperative hypertensive crises during surgery.

- Prognosis varies depending on tumor size, location, and malignant potential.

- Long-term surveillance is crucial for the early detection of recurrence or metastasis, especially in patients with hereditary forms.

- Complications of paragangliomas and their treatment may include neurological deficits, vascular injury, recurrence, and metastasis.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patients with paragangliomas are at risk for malignant hypertension, cranial nerve injury, hemorrhage, stroke, arrhythmia, myocardial infarction, and death. Early identification, management, and development of a cohesive interprofessional team will decrease the morbidity and mortality associated with this rare but complex condition.

Primary care, critical care, endocrinology, oncology, surgery, radiology, pharmacy, genetics, nursing, and anesthesiology healthcare professionals all require the necessary knowledge to diagnose and manage patients with paragangliomas. This includes understanding the nuances and associated risks of the various treatment options. Each healthcare professional must know their responsibilities and contribute their unique expertise to the patient's care plan, fostering a multidisciplinary approach.

Ensuring seamless interprofessional communication and a multidisciplinary approach ensures patients are prepared for surgery adequately and appropriately monitored post-operatively and over their lifetime. Embracing a multidisciplinary approach with interprofessional responsibilities and communication will improve patient outcomes and quality of life.