Continuing Education Activity

Lumbosacral discogenic syndrome is a prevalent cause of axial low back pain (ALBP) that can result from various structures such as facet joints, spinal muscles, and ligaments. ALBP is a significant clinical and socioeconomic burden globally, leading to substantial healthcare costs. To address this challenge, healthcare professionals must accurately diagnose and treat the condition. This informative CME activity provides a comprehensive review of the assessment and management of lumbosacral discogenic syndrome while emphasizing the crucial role of an interprofessional healthcare team in evaluating and treating patients with this condition. Participants gain valuable insights into this syndrome's pathophysiology, evaluation, and treatment, mainly focusing on pain originating from intervertebral disc pathology.

Objectives:

Identify clinical presentations and relevant imaging findings indicative of lumbosacral discogenic syndrome, distinguishing it from other lumbar spine pathologies.

Implement evidence-based treatment strategies encompassing conservative measures or tailored interventions for different lumbosacral discogenic syndrome stages.

Assess treatment outcomes, monitoring pain relief, functional improvement, and patient satisfaction post-intervention, adjusting management plans as needed.

Collaborate with the interprofessional team to provide care and follow-up for patients with lumbosacral discogenic syndrome to enhance patient outcomes.

Introduction

Low back pain is a common cause of disability among the general population, with a well-documented cost burden placed on the U.S. healthcare system. There are multiple sources of chronic low back pain, often divided into whether the pain is facet-mediated, myofascial, herniation-related, secondary to fracture, or discogenic in nature. This article will focus on the pathophysiology, evaluation, and treatment of lumbosacral discogenic syndrome and pain arising from intervertebral disc pathology.

Intervertebral discs are pads of fibrocartilage that sit between the spinal vertebrae, occupying roughly one-third of the height of the spinal column.[1] Their primary role is transmitting mechanical loading from body weight and muscle activity, allowing bending, flexion, and torsion of the bony spine.

Each disc has two main components: a central, gel-like substance called the nucleus pulposus and an outer, firmer annulus fibrosis. The consistency of the nucleus is due to its water and proteoglycan content and is held together by a network of type II collagen and elastin fibers. This network's high anionic glycosaminoglycan content gives the nucleus pulposus its osmotic properties, allowing it to resist compression. The annulus fibrosis comprises bundles of type I collagen arranged in multiple oblique layers called lamellae. Characteristics of a normal, healthy disc demonstrate high water content in the nucleus and inner annulus. The outermost annulus provides tensile strength. A healthy disc is typically 7 to 10 mm thick and 4 cm in diameter in the lumbar region, with approximately 20 layers of lamellae.[1]

The sinuvertebral nerve (SVN) supplies the interverbal discs, which innervates the posterior annulus and posterior longitudinal ligament. In healthy subjects, the neural penetration of the annulus is about 3 mm, corresponding to the outer three lamellae. It is a mixed nerve containing a somatic root from the ventral ramus and an autonomic root from the grey ramus. Once the nerve takes a recurrent course through the intervertebral foramen and enters the spinal canal, it divides into superficial and deep networks. The superficial network branches to multiple vertebral levels and contains mostly sympathetic fibers, while the deep network contains primarily somatic fibers and innervates the corresponding segment.[2]

The intervertebral discs are relatively avascular, with the nucleus and inner annulus being supplied by capillaries that arise in the vertebral bodies and terminate at the bone-disc junction. Nutrients and small molecules such as glucose and oxygen reach the disc cells by diffusion.[3] Additionally, only the outermost portion of the annulus is vascularized. As a result, intervertebral discs are very limited in their ability to heal from injury, and degenerative changes overtake the healing process. This is not just due to avascularity but also to a decreased cell population, which diminishes the structure's ability to break down and turn over large collagen bundles.

Axial back pain may be of discogenic origin. However, not all damaged or degenerated discs cause pain. Disc abnormalities are commonly seen on MRI in asymptomatic individuals. Considering other possible axial low back pain etiologies with similar clinical presentation, this presents a challenge to the treatment provider.

Etiology

Distinguishing the difference between age-related changes and disc degeneration is essential. After young adulthood, nucleus cell density decreases, and the proportion of senescent cells increases, resulting in an accompanying decrease in proteoglycan content, disc water content, and extracellular matrix turnover.[4] As a result, the annulus becomes stiffer and must resist compression directly.

An additional finding can be the detachment of the hyaline cartilage endplates due to this loss of internal pressure. The nucleus also tends to bulge into the vertebral body, leading to radial bulging of the annulus and subsequent disc height loss. As a result, compressive stresses are placed on the neural arches, leading to facet osteoarthritis and osteophyte formation. This can lead to a further source of axial back pain. Other aging features are decreased vertebral endplate permeability and metabolite transport. This is a noteworthy difference from disc degeneration, where damage leads to an increase in these features.

Adams et al define disc degeneration as an aberrant, cell-mediated response to progressive structural failure. Signs of accelerated or advanced aging accompany structural failure. Disc degeneration causes include genetic inheritance, advanced age, inadequate metabolite transport, and loading history. These elements provide the setting for structural failure to occur with normal activities of daily living.[4]

Characteristics of structural damage include endplate fracture, radial fissuring, and herniation. Due to the lumbar spine’s function as a significant motion segment, this region often shows annular disc tearing. There are three types of annular tearing. Circumferential tearing results from shear stresses. Peripheral tearing is usually located in the anterior annulus and is likely related to trauma. Radial tearing is associated with nucleus degeneration and posterior projection. The disc is herniated or prolapsed if the nucleus migrates enough to affect the periphery. The extent of migration can result in protrusion, extrusion, or sequestration of the disc material. Additionally, damage or fracture to the vertebral endplate induces the increased activity of degradative enzymes and pro-apoptotic factors.[5]

Epidemiology

Lumbar intervertebral discs are shown to be a source of chronic back pain in 26% to 42% of patients with disc herniation.[6] Disc tearing is common in the lumbar spine, peaking in middle age. Determining the prevalence of intervertebral disc degeneration is difficult, as most cases are asymptomatic. A systematic review performed by Brinjikji et al looked at asymptomatic patients who underwent lumbar MRI and found that the prevalence of disc degeneration ranged from 37% of asymptomatic individuals 20 years of age to 96% of those 80 years of age, with a significant increase in the prevalence through 50 years.[7] This suggests that imaging findings defining degenerative changes are products of normal aging instead of pathological processes requiring some intervention.

Pathophysiology

Intervertebral disc degeneration is a cellular, pro-inflammatory, and molecular process. Aging, genetic disposition, and abnormal mechanical loading all contribute to the acceleration of this process. Disc pain arises from sensitization secondary to the ingrowth of nerve fibers within annular fissures. In a healthy disc, neural penetration through the annulus is about 3 mm. Degenerative discs have shown penetration deeper into the inner third and even the nucleus of the disc.[2] Exposure of the nucleus to the outer annulus and neuronal tissue results in the attraction of inflammatory mediators. The result is hyperinnervation and hyperalgesia related to the leakage of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Studies have demonstrated an increase in nerve growth factor in those individuals with discogenic pain.[8] Furthermore, degenerated discs show a greater density of nerve fibers within the respective endplates than healthy endplates.

History and Physical

Patients with discogenic pain will typically report pain in the midline or the immediate paraspinal region with occasional radiation to the flanks or buttocks. The pain is typically worse with axial loading, sitting, or lumbar flexion and relieved with lumbar extension or lying supine. It is also not uncommon for patients to experience associated stiffness. Given the broad differential diagnosis for non-radicular, axial low back pain and similarity in clinical features, physical exam maneuvers are relatively poor in accurately diagnosing discogenic pain. Therefore, there are no specific physical tests for diagnosis.

Evaluation

As discogenic pain shares clinical features with other etiologies of axial low back pain, further workup ranging from radiographic imaging to interventional procedures is often necessary. Disc degeneration can be seen on imaging in asymptomatic individuals, and findings positively correlate with age. Therefore, positive results on imaging must be taken in the context of the patient’s presentation. Conventional radiographic findings include disc-space narrowing, vacuum disc phenomenon due to accumulation of nitrogen in degenerative fissures, endplate sclerosis, and osteophyte formation. CT can identify these same changes earlier during the disease process. MRI is the modality of choice to evaluate disc degeneration due to superior soft-tissue contrast. A High-Intensity Zone (HIZ) is an MRI finding seen on T2-weighted imaging as a hyperintense signal within the posterior annulus that has been shown to correlate with annulus damage as well as pain.

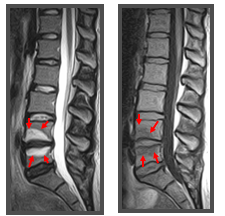

Additional findings include Modic changes, which are degenerative changes in the vertebral endplates and bone marrow. There are 3 types of Modic changes based on T1-weighted and T2-weighted characteristics. Type I Modic changes are seen as a low signal in the endplates and adjacent marrow on T1-weighted imaging but hyperintense on T2-weighted imaging (see Image. Modic Changes). These changes are highly associated with disc degeneration and pain and have high specificity for positive discography.[9]

Provocative discography is a fluoroscopically-guided diagnostic procedure involving the deliberate administration of contrast into the nucleus pulposus of the suspected painful disc. The pressurized injection of contrast simulates mechanical loading and induces pain. Additionally, the pattern of contrast spread indicates the degree of disc disruption. This procedure is only performed when there is a high pretest probability of discogenic pain based on patient presentation and imaging. This is in part due to potentially significant post-procedural complications, including diskitis, dural puncture, disc rupture from contrast overpressurization, and worsening of underlying disc degeneration. Defining sensitivity and specificity for the procedure is challenging as there is no other gold standard for comparison. Due to variability in technique and interpretation, there is no consensus regarding the false-positive rate. However, systematic review and meta-analysis suggest a rate of about 9.3% per patient.[10] Given these considerations, the procedure should only be performed if it will make a clear difference in management.

Treatment / Management

As with other causes of axial low back pain, a conservative approach with physical therapy and home exercise is the first step in treatment. Regarding pharmacological therapy, NSAIDs may provide moderate efficacy, but long-term use should be monitored due to the impact on the gastrointestinal and genitourinary systems. Regarding opioids in the treatment of chronic back pain, evidence for efficacy is scant in systematic reviews. Additionally, randomized controlled trials are few. Though opioids appear to have short-term efficacy in treating chronic back pain, the improvements in function are unclear.[11] Furthermore, long-term opioid use is associated with well-known effects such as hyperalgesia, tolerance, and potential addiction and overdose. As a result, the CDC has cautioned against the routine use of opioids in the treatment of chronic low back pain. It is recommended that clinicians carefully reassess evidence of risk and benefit when considering an increase to 50 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) or more per day and avoid increasing the daily dosage to 90 MME or more.[12]

Many interventional therapies are used to target discogenic pain that is unresponsive to conservative management. These include epidural steroid injection, nucleoplasty, intradiscal injection, intradiscal electrothermal therapy (IDET), and biacuplasty. Epidural steroid injection has been shown in a systematic review to have fair efficacy in treating discogenic pain.[13] The underlying mechanism may involve a corticosteroid-related reduction in pro-inflammatory mediators. IDET and biacuplasty involve the application of heat to destroy sensory fibers innervating the disc. IDET involves the fluoroscopically-guided placement of an active tip near the area of damage. Biacuplasty creates heat across the posterior annulus using a cooled bipolar radiofrequency device. A systematic review by Helm et al looking at multiple randomized controlled trials involving these intradiscal thermal therapies concluded level I evidence favoring the efficacy of biacuplasty in treating discogenic chronic LBP, whereas IDET showed level III (moderate evidence) of efficacy.[14]

Proposed treatments also include injection with glucocorticoid and stem cell solutions. A randomized controlled trial performed by Nguyen et al demonstrated poor long-term efficacy of discogenic pain treated with intradiscal corticosteroids.[15] Intradiscal biological therapy with platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is an emerging treatment option. PRP is an autologous blood concentrate containing growth factors and cytokines. The PRP concentrate induces tissue regeneration and repair through anabolic and anti-inflammatory effects. In vitro and animal studies have shown the restoration potential of intervertebral discs. However, there is a dearth of double-blind, randomized controlled trials studying intradiscal PRP, though other studies support its safety and analgesic effects.[16] Additionally, the preparation of the concentrates is variable. Therefore, more large-scale randomized controlled studies are needed.

Lastly, surgical fusion is also a proposed treatment for patients who have discogenic pain refractory to conservative and minimally invasive therapies. Currently, there is debate regarding the surgical management of discogenic pain with varying results according to different studies.[17] As a substitute for spinal fusion, artificial disc replacement is another more recent therapy intended to help with pain while also preserving the lumbar spine’s function as a motion segment. This may also help prevent adjacent segment disease typically seen post-fusion. Though further studies are needed, a recent meta-analysis showed significant improvement in the Oswestry Disability Index, satisfaction, and a decrease in reoperation rate compared to fusion.[18] Additionally, as the procedure is performed through the abdomen or retroperitoneum, there is theoretically a decreased risk of muscular dissection compared to posterior fusion, which could result in less postoperative pain.

Differential Diagnosis

As discogenic pain is axial, other causes of axial back pain should be considered. This includes facet arthropathy, paraspinal muscle sprain or strain, ligament sprain or strain, lumbar spondylosis, lumbar spondylolysis, and lumbar spondylolisthesis. A detailed history, careful physical exam, and pertinent imaging can help narrow the differential diagnosis and help a practitioner make the correct diagnosis.

Prognosis

Of the patients with chronic low back pain who remain disabled for more than 6 months, less than half ultimately return to work. After 2 years, this becomes statistically much less likely.[19] For Americans younger than 45, chronic LBP is the most common cause of disability, irrespective of etiology. Therefore, conservative treatment should begin as soon as possible. Regarding chronic low back pain, poor prognostic factors include emotional distress, ongoing litigation, somatization, and chronic tobacco use.[20][21] Favorable prognostic factors include good social support and symptoms consistent with findings on MRI.

Complications

The complications of discogenic pain include significant disability as well as effects on the psychological well-being of patients. There can be a significant increase in stress, depression, and anxiety after the onset of low back pain. In the setting of very progressive degenerative disc disease, the loss of disc height can decrease the foraminal diameter, resulting in compression of the nerve root and radiculopathy.

Deterrence and Patient Education

A benefit of having the patient engage in physical therapy early includes patient education in managing and preventing worsening symptoms. Patients can learn about mechanical loading strategies, provide postural education, a walking program, and receive lumbar taping. The McKenzie method is a comprehensive approach to chronic low back pain that includes both an assessment and an intervention and incorporates the patient’s directional preference.[22] Depending on the underlying pathology, the patient is provided information about specific postures and repetitive movements.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Chronic low back pain, including discogenic etiology, is an interprofessional problem involving primarily physical therapists, primary care physicians, orthopedists, neurosurgeons, and pain medicine specialists. Interprofessional communication must be encouraged through gathering, lecturing, and sharing recent updates in treatment. Given this disease's societal and economic burden, all practitioners are responsible for addressing this issue, given the strains on global healthcare costs.

Furthermore, given the lack of specificity of axial low back pain and often seen positive imaging in many asymptomatic patients, emphasis should be placed on proper collection of medical history. This can help prevent unnecessary treatments and risk of harm to the patient.