History and Physical

Patients with PPC usually present with defective near and distant vision, glare, halos, difficulty reading small words, problems driving a vehicle during the night, photophobia, and reduced contrast sensitivity. The problem increases with age due to senile miosis and increased density of the PPC. The symptoms probably result from vacuole-like changes in the surrounding area of discoid opacity. If present during childhood, it can result in defective vision, amblyopia, and deviation of the eyeball manifesting as exotropia. As the age increases, the anatomical (in the bag placement of IOL without posterior capsular breach) and the patients' functional (visual) expectation also increases.[14]

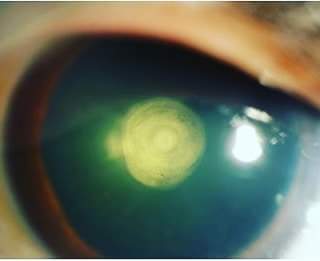

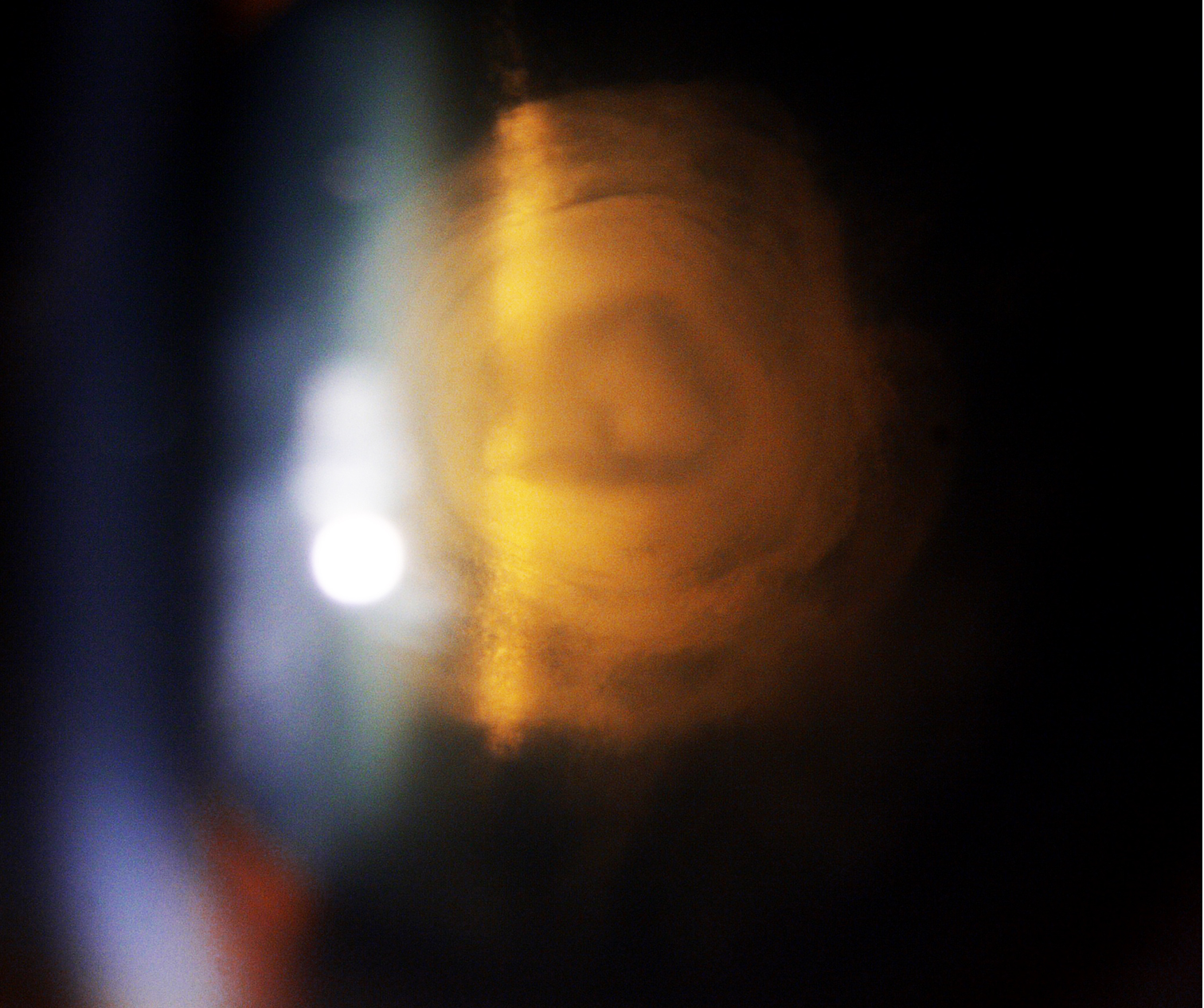

The diagnosis of PPC is clinical and can be easily made with a meticulous slit-lamp examination. Retro illumination reveals a thick white circular discoid plaque-like central opacity in the form of onion rings densely adherent to the posterior capsule. This typical appearance has also been described as a bull's eye appearance. The thickness and the breath of the opacity are a fair indicator of visual acuity also. Larger and thicker opacities affect the visual acuity more compared to the smaller ones. They are rarely picked up in infancy compared to anterior polar cataracts, which are quite evident during birth. While examining the anterior vitreous phase, it may appear like oil droplets suggesting a pre-existing posterior capsular defect. In a study, the mean PPC lens thickness was comparatively lower than that of senile sclerotic cataracts. Another study demonstrated that the mean age of patients in PPC was lesser than that of senile cataracts.[16]

PPC can also present with posterior subcapsular cataracts, cortical cataracts, and nuclear sclerotic cataracts. Sometimes dense white spots are noticed adjacent to the PPC, suggestive of the thin or absent posterior capsule. This is known as the Daljit Singh sign. When the PPC plaque is examined by a 60-degree slit, if there is a bend of rays at the center, this also signifies posterior capsule dehiscence.[13]

Classification Systems for Posterior Polar Cataract

Duke-Elder Classification System

Stationary PPC - This is the more common type seen in 65% of cases; it is a round, well-defined, localized opacity located on the posterior capsule. The onion ring appearance of PPC gives it the shape of a bull's eye. Very rarely, the opacity is masked by nuclear sclerotic cataracts. Occasionally satellite lesions are observed surrounding the opacity. The progression may be noted at any time.

Progressive PPC- The lenticular changes are present in the form of whitish opacity at the posterior cortex in the shape riders. The edges are feathery and don't involve the nucleus. It may also become symptomatic. The opacity affects the visual acuity, usually by the age of 30 to 50 years.[3]

Daljit Singh's Classification[20]

|

Type

|

Description

|

|

1

|

Presence of posterior polar cataract along with posterior subcapsular cataract

|

|

2

|

Onion ring-shaped posterior polar cataract with presence or absence of white spot at the edge

|

|

3

|

Discrete round or oval opacity at the center with surrounding white spots at the edge. This is usually associated with thin or absent posterior capsule

|

|

4

|

Combination of any of the above three along with nuclear sclerosis

|

Singh, in his analysis, proposed that type 2 can convert to type 3, and it is not a wise option to delay surgery in PPC cases.

Schroeder's Classification

He classified PPC in pediatric patients based on the obstruction in the red reflex through the pupil[21]

|

Grade

|

Description

|

Management

|

|

1

|

Very small PPC without any effect on the visual acuity through the clear part of the lens

|

Patching

|

|

2

|

PPC obstructing two-third part of the pupil

|

Patching with mydriasis and bifocal glasses

|

|

3

|

PPC with the surrounding area of optical distortion. A clear red reflex is appreciated only through a dilated pupil

|

Patching and early surgery

|

|

4

|

Large PPC, no red reflex is observed even through a dilated pupil

|

Patching and early surgery

|

Schroeder advised patching before surgery in PPC patients as it will be helpful to diagnose and treat amblyopia and post-surgical management. He proposed that if patching works well, surgery can be delayed in these cases. The above classification will also be helpful for planning surgery in these patients. The larger and denser the opacity, and earlier the area of pupillary obstruction surgery should be done.

Vasavada's Classification of Posterior Polar Cataract[14]

Vasavada divided PPC into three distinct varieties

- PPC with impending posterior capsular dehiscence

- Pre-existing capsular dehiscence with PPC

- Spontaneous dislocation of PPC

Evaluation

Visual Acuity and Refraction

Snellen’s visual acuity documentation of uncorrected and best-corrected visual, near vision, and pinhole vision is very important in these cases. The corrected distant visual acuity is an indirect indicator of the size and density of PPC.

Undilated and Dilated Fundus Evaluation

To rule out any incidental fundal pathologies and this also helps in deciding the prognosis of the case. Postoperatively, cases resulting in posterior capsular rent must undergo a retinal evaluation to rule out nucleus or cortex drop or signs of retinal detachment.

A-Scan Ultrasonography

To calculate the axial length, keratometry readings, and intraocular lens power for implantation.

B Scan Ultrasonography

In the case of dense opacities where media is hazy and the fundus is not visible, a B scan must be done to rule out retinal pathologies. In case of any retinal or optic disc pathology on B scan, the patient should be counseled in detail regarding visual prognosis. This also helps in planning future treatment of the patient with the help of a retina specialist. Guo et al. utilized 25 MHz B scan USG for delineating the posterior capsular status in PPC and proposed that this can be a valuable tool in guiding the management of these cases.[22]

Anterior Segment Optical Coherence Tomography (ASOCT)

ASOCT is a beneficial tool to assess the status of the posterior capsule preoperatively. All PPC patients must undergo preoperative ASOCT evaluation to rule out pre-existing PC dehiscence; this helps the ophthalmic surgeon plan case management and be prepared for any possible intraoperative mishap. ASOCT is a valuable tool for counseling the patients regarding visual prognosis and the outcome of the surgery.[23]

Intraoperative Anterior Segment Optical Coherence Tomography

The diagnosis and management of ASOCT have taken a leap forward, with intraoperative OCT guiding the surgical steps of PPC. Titiyal et al. described the posterior polar cortical disc defect (PPCDD) sign in PPC cases while performing phacoemulsification. They proposed that the presence of this sign is an indicator of an intact posterior capsule and the risk of PCR is comparatively lower in these patients compared to patients without PPCCD signs.[24]

Modified Posterior Optical Coherence Tomography

Pujari et al. defined conical sign with +20 dioptre and modified posterior optical coherence tomography (m-OCT). They showed that the presence of a conical defect is an indicator of pre-existing posterior capsular dehiscence and guides the intraoperative and postoperative management of these cases.[25]

Other Tests

Complete blood count, kidney function test, pulmonary function testing by a specialist, electrocardiogram, and physician evaluation are necessary when indicated before surgery. The patient should be systemically stable to undergo the surgical intervention.

Treatment / Management

Medical Treatment

Medical treatment has a limited role in PPC management. Only syndromic patients with systemic involvement may need treatment with the help of a physician or other clinician. Pediatric patients presenting with PPC should be thoroughly evaluated for rare systemic syndromes. Kronenberg et al. reported PPC in patients with neurocutaneous syndrome. Similarly, Duke-Elder reported PPC in patients with ectodermal dysplasia, ichthyosis, scleroderma, dyskeratosis congenita, and Rothmund syndrome.[1][6]

Surgical Management

Indications for Surgery

Excessive glare and photophobia, difficulty in reading fine prints, and difficulty in carrying out routine activities are all indications for surgery. Another indication is early type 1 and 2 PPC when the nucleus is soft, and the risk of complication is less. Pediatric PPC should be operated on as soon as possible to prevent the risk of blindness.[20]

Surgery of Choice

Phacoemulsification and manual small incision cataract surgery are the surgical techniques commonly employed for PPC management based on patient affordability, surgeons' expertise, and indication for surgery.[14] Extracapsular cataract extraction (ECCE) was previously used for PPC management, but recently it's being replaced MSICS due to high astigmatism and the need for multiple sutures.[26] Osher et al., in their analysis, showed that the incidence of PCR was nearly the same with phacoemulsification and ECCE.[7]

In contrast, Das et al. showed that the rate of complications was more with ECCE. Hence phacoemulsification is the surgery of choice.[26] Vasavada et al. found that PCR was most common during epinucleus removal in PPC while performing phacoemulsification.[14] In the west, phacoemulsification is more commonly performed compared to MSICS in India. In India, patients with poor socioeconomic strata usually undergo MSICS, being a commonly performed surgery. Hayashi et al., in their analysis, proposed phacoemulsification for soft PPC <4 mm and pars plana approach for PPC > 4 mm. For dense PPC >4 mm, they suggested ICCE. In a nutshell, the most commonly employed technique is phacoemulsification.[16]

Surgical Anesthesia

In today's era, topical anesthesia is the anesthesia of choice for phacoemulsification. However, some surgeons prefer peribulbar or retrobulbar anesthesia depending on the density of PPC, patients' age, systemic comorbidities, patients' cooperation on the table, other eye conditions, confidence, and surgical expertise of the surgeon while operating PPC. Sometimes during topical anesthesia, the patient squeezes the lids, which contributes to positive vitreous pressure. Excessive vitreous pressure acts as an added risk factor for intraoperative PCR. A gentle massage post peribulbar or retrobulbar block is suggested to reduce vitreous pressure.[14]

Anterior Approach

Corneal Incision Placement

The main corneal incision can be temporal or superior. The preferred incision is a temporal clear corneal 2.8 mm incision with two side port incisions. Consideration is given to straight clear corneal incision due to the ease of conversion to SICS or ECCE during posterior PCR. A straight clear corneal incision is easy to extend without causing trauma to the posterior cornea. The sclerocorneal incision helps reduce astigmatism and endothelial trauma.[27]

Ophthalmic Viscosurgical Devices ( Viscoelastic)

The viscoelastic of choice is a dispersive one; it aids in corneal endothelial protection, tamponade the vitreous during vitrectomy, and viscodissection of the nucleus.[28]

Capsulorhexis

Rhexis size should be about 5.5 mm to 6 mm for good sulcus support for IOL placement in the case of PCR. A small rhexis invites difficulty in delineation and phacoemulsification and also postoperative capsular phimosis, whereas a large rhexis helps in easy delineation and optic capture.

Hydro Procedures

As a general rule, hydrodissection is contraindicated in the case of PPC. The recommendation is for hydrodelineation by the inside-out technique. Some surgeons have also described multiple partial jets of hydrodissection while removing PPC, but it should be avoided ideally. Some surgeons prefer viscodissection for the separation of the nucleus from the epinucleus and cortex.[16]

Phacoemulsification and Dynamics

A good interplay of appropriate pharmacodynamics is important for excellent outcomes in case of PPC cases. The ideal scenario is wound with a minimum leak, adequate vitreous pressure, and perfect phaco machine parameters. For soft PPC, lower energy settings are recommended with the torsional mode in recent newer phaco machines. Nucleus rotation is contraindicated in PPC to prevent PCR and zonular dialysis. A low vacuum with a lower aspiration flow rate is recommended. The nucleus should be emulsified before manipulating the PPC component, which prevents nucleus or cortex drop in the vitreous cavity in case of PCR.

Various techniques have been described, like pre-chopping and sculpt and chop to avoid stress and manipulation of PPC. The nuclear material removal is followed by epinucleus and cortical material. In the case of soft PPC, the nuclear material should be fed to the phaco probe with the help of sinskey or the chopper.[29]

Doing this reduces tension on the central PPC component and also reduces the need to strip the cortical material under stress. Vacuum should be employed judiciously, as it can result in PCR. Dense nucleus material can be cracked into multiple small fragments and removed with minimal or no stress on the central component keeping the probe in the center. The epinucleus and cortical matter can be removed or freed leaflet by leaflet from the periphery to paracentral area avoiding stripping of the central PPC fragment. In most cases, the PPC comes in toto without compromising the integrity of the posterior capsule.

In case of a PCR, the dispersive viscoelastic and anterior vitrectomy should be ready to manage the vitreous prolapse. The other school of thought is removing the central PPC component with the help of a vitrectomy probe or by performing a posterior capsulotomy. After a thorough anterior vitrectomy. the IOL can be placed in the sulcus.[30] The morphology of PPC and status of the posterior capsule can be judged preoperatively with the help of ASOCT. Pujari et al. categorized PPC into three types conical, ectatic and moth-eaten, based on ASOCT appearance.[31]

Phacoemulsification Parameters

The ideal parameters described for management for PPC are 60% power, a bottle height of 50-70 cm, the aspiration flow rate of 15 to 25 mL/min, and a minimal vacuum of 30 to 100 mm. These parameters prevent stress on the posterior capsule and help in a very stable anterior chamber.[7]

Nucleotomy Techniques

Phacoaspiration

This process is recommended for soft PPC. While dealing with such a scenario, it is assumed that the posterior capsule is absent below the PPC.

Phaco Chop

This process is recommended for harder PPC plaques. Phaco chop help to reduce stress on the posterior capsule. It is important to avoid anterior chamber collapse as it can result in spontaneous posterior capsule rupture. Before withdrawing the phaco probe, the chamber should be filled with dispersive viscoelastic through the side port to prevent spontaneous rupture. Moreover, aggressive nuclear rotation, vigorous cracking maneuvers, and wider and deeper separation of fragments should be avoided to prevent PCR.[1]

Lambda Technique

Lee et al. described the lambda technique where the nucleus is sculpted in a λ shape. This is followed by a crack along the arms and quadrant removal of the central piece. This technique prevents stretching and rupture of the capsule.[13]

Inverse Horseshoe Technique

Salahuddin proposed this technique in which the distal portion of the nucleus is divided after sculpting. This is followed by OVD injection to elevate the two portions of the nucleus, thus forming a Visco shell. This technique helps in the hemi-dissection of the nucleus without the stretch of the posterior capsule. Later the individual nuclear fragments can be chopped and emulsified as usual.[32]

Epinucleus Pre-chop Technique

Lim and Goh described a technique of pre-chopping the epinucleus without reaching the depth of the posterior capsule and epinuclear plate. This is helpful for hard PPCs where the nucleus can be quickly mobilized by separating it from the anterior epinucleus shell.[29]

Peripheral Crack Technique

Chee described this technique for hard PPCs by partially cracking the nucleus in the periphery and further chopping the nuclear pieces in multiple quadrants without rotation. In this way, the posterior polar opacity is not manipulated, and the nucleus is separated from the outer nuclear shell with the help of the chopper.[33]

Reverse Flower Bloom Technique

In this technique, first, the nuclear material is removed without disturbing the integrity of PPC. In the second step, the cortical matter is peeled by the outside-in technique (mimicking a reverse blooming flower), leaving the PPC intact. In the last step, the poster polar attachment is separated gently from the capsule.

Predivision Technique

Kamoi and Mochizuki described this technique where a pre-chopper creates two pre-chops on both sides of the central part. This is followed by central fragment removal, thus creating space in the capsular bag to remove further fragments easily.[34]

Posterior Approach

Pars plana lensectomy with vitrectomy has been described to prevent unwanted complications of PCR and nucleus drop. Few authors have also described the posterior approach through the pars plana route with variable outcomes. In a study of 11 eyes of 8 patients with this approach, three eyes developed posterior segment complications.[35] Another study used the pars plana approach for 2 out of 28 eyes in large PPC having a soft nucleus.[16] As a general consensus, this technique can be avoided due to the high risk of complications associated with vitrectomy

Epinucleus Removal

Vajpayee et al. described the layer by layer technique for removing epinuclear plate in cases of the pre-existing posterior capsular breach, which can be picked clinically or using ASOCT. While performing layer by layer removal of epinucleus, care should be taken to leave the central area untouched without undue stress on the posterior capsule. The PPC plaque can be easily viscodissected in the end.[33]

In another technique by Fine et al., epinucleus can be removed by pure viscodissection without unnecessary pressure on the posterior capsule.[36] Allen and Wood used the similar principle of viscodissection. They proposed that nucleus rotation should be avoided, and the epinucleus can be easily peeled off by injecting viscoelastic between the cortex and capsule.[37] In a landmark study by Taskapili et al., they compared outcomes of PPC with and without cortical viscodissection. They reported that the rate of posterior capsular rupture was higher in the without viscodissection group.[28]

Nagappa et al. described loosening of the epinucleus by phacoaspiration in the quadrant opposite the wound. This is followed by the removal of the sub incisional cortex by loosening it with hydrodissection. They reasoned that the hydrodissection wave doesn't cause posterior capsular rupture because the fluid escapes the path of least resistance in the epinuclear free area. They also proposed that this technique would be contraindicated in cases of pre-existing PCR detected clinically or by ASOCT.[38]

Pseudohole Sign

Sometimes after removing posterior polar opacity, the impression of the onion ring is seen on the posterior capsule. This impression gives the appearance of a hole, but since the posterior capsule is intact, it has been labeled as a "pseudohole sign." Nagappa et al. were the first to describe the "fish mouth sign" as the sign of posterior capsular rupture when vitreous prolapse is seen through the PPC defect.[38]

Cortex Aspiration

The cortex removal should be performed with a bottle height of around 15 to 25 cc/min. The cortex should be pulled tangentially rather than the usual pulling centrally to avoid stress on zonules and prevent rupture of the posterior capsule. Vajpayee et al. proposed cortical removal by the "layer by layer "technique. In this technique, they described the removal of the cortex in a wedge-shaped manner and then separated with the help of a chopper; this prevents stress on the central plaque of PPC and prevents PCR. Another technique is the dry aspiration of the cortex with the help of Simcoe cannula (5 cc syringe) by filling the capsular bag with viscoelastic. It has also been proposed that capsular polishing should be avoided in these cases.[39]

Removal of the Posterior Polar Plaque

The general rule is PPC plaque should be left untouched till the end of the surgery (cortical aspiration). At the last step, the plaque should be separated by viscodissection. The separated plaque then should be lifted and can be aspirated with the help of a phaco tip or by bimanual irrigation and aspiration. Another proposed technique is filling the capsular bag with viscoelastic and then dislodge the plaque with a sinskey hook. The separated plaque can then be easily removed with the help of forceps. This will avoid the drop of PPC plaque in the vitreous cavity. Osher described the technique of "minimal residual aspiration."[28] In this technique, the PC is cleaned with the minimal touch of the PC with the help of irrigation and aspiration tips. If the PPC plaque is densely attached to the posterior capsule and the surgeon cannot dissect it by viscodissection, the plaque can be left in situ and later removed by Nd-YAG capsulotomy.[16]

Managing Posterior Capsular Tear

Once the posterior capsular tear is noticed, viscoelastic must be injected before removing the phaco probe to form the anterior chamber and prevent disruption of the anterior vitreous face. Dispersive viscoelastic must be injected to tamponade the vitreous and seal the posterior capsular rent. If possible, the rent can be fashioned into a posterior capsulorhexis, and then the intraocular lens can be easily placed in the bag. In case of an irregular tear, the IOL can be placed in the sulcus after a thorough anterior vitrectomy.

Anterior Vitrectomy

Bimanual vitrectomy is recommended for cutting the anterior vitreous. High cut rate and low vacuum vitrectomy can be easily performed close to the rent. The vitrector is held in the dominant hand, and the infusion cannula should be held in the non-dominant hand directed towards the angle away from the rent. This helps to prevent vitreous hydration, vitreous prolapse, and enlargement of the tear.

Intraocular Lens Implantation

If the PCR is small, it can be converted to a round posterior capsulorhexis, and a single piece of IOL can be easily implanted in the capsular bag. If the PCR is large and irregular, a piece of IOL can be implanted in the ciliary sulcus, or an optic capture can be done. Optic capture helps in IOL stabilization and prevents iritis due to iridolenticular touch. Mackool, in his analysis, proposed that PMMA IOL is a better option than foldable IOL, as haptics of foldable IOL can stretch the PC and may enlarge the rent. In case of lack of adequate support for IOL, an ACIOL can be implanted or an iris-claw lens of a scleral fixated IOL.

Viscoelastic Removal, Wound Hydration, and Anterior Chamber Formation

Once the IOL has been implanted and is stable, viscoelastic should be thoroughly washed by irrigation and aspiration, and the incision should be hydrated. The anterior chamber should be formed with the self-sealing corneal incision. In case of PCR and vitreous prolapse and micro leaks, the main and side port incision should be sutured to prevent vitreous prolapse and endophthalmitis.