Introduction

The Sylvian fissure is the most consistent and distinct landmark of the lateral hemispheric surface of the brain.[1] It is formed by the anatomical relationship between the frontoparietal operculum, the temporal operculum, and the insula. The arachnoid membrane covers the fissure creating the Sylvian cistern, a subarachnoid space that contains important vascular structures surrounded by cerebrospinal fluid. The splitting of the Sylvian fissure, opening the arachnoid layer between the opercula, exposes the superficial Sylvian vein, the middle cerebral artery, the deep middle cerebral vein, and the insula.[2]

The first depiction of the lateral fissure of the brain is attributed to Girolamo Fabrici d’Acquapendente, in one of the plates of his Tabulae Pictae, from 1600. Forty-one years later, in 1641, Thomas Bartholin published the first description and graphic representation of the fissure in the book Casp. Bartolini Institutiones Anatomicae.[3] In 1663, Franciscus de la Böe (Dr. Sylvius) published his book Disputationem Medicarum, where the author described the lateral cerebral sulcus, which thereafter became known as the Sylvian fissure, honoring his name.[4]

Structure and Function

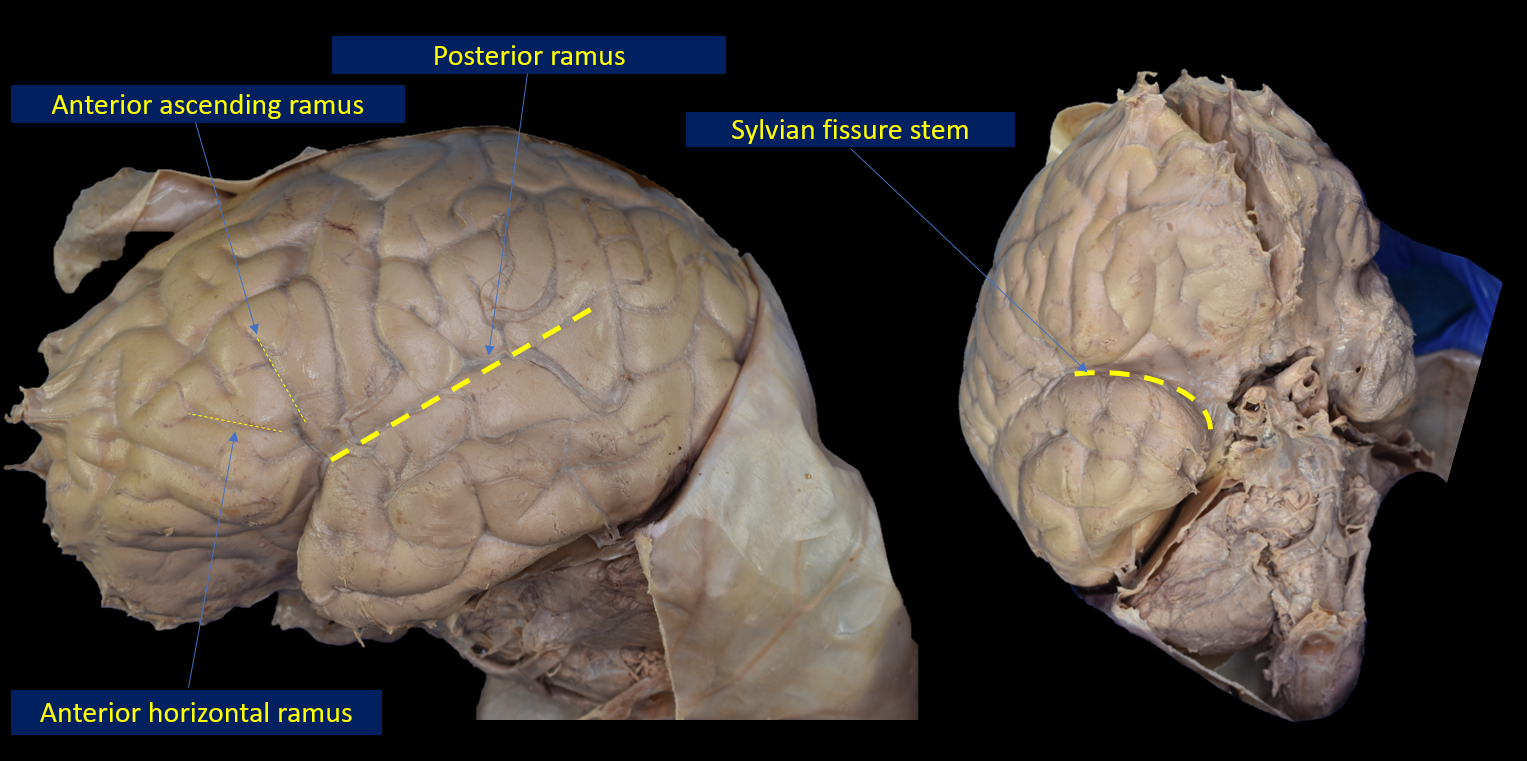

The Sylvian fissure can be divided into two parts: superficial and deep. The superficial part is visible on the brain's surface and is divided into a stem and three rami: posterior ramus, anterior ascending ramus, and anterior horizontal ramus. The deep part is located below the brain's surface and is divided into two compartments: sphenoidal and operculoinsular.[1][5]

Superficial Part

The superficial part of the Sylvian fissure can be appreciated on the brain's lateral and basal hemispheric surfaces, between the frontal, parietal and temporal lobes (Figs. 1 and 2). It is divided into a stem on the basal surface and three rami on the lateral surface. The stem arises lateral to the anterior perforated substance. It is directed laterally and anteriorly, between the temporal pole and the orbital gyri, towards the lateral surface of the brain. The Sylvian fissure stem has an important topographic relationship with the lesser wing of the sphenoid bone. The stem starts medially to the anterior clinoid process, stays behind the lesser wing of the sphenoid bone following the sphenoidal ridge, and ends at the level of the pterion, in the lateral margin of the sphenoidal ridge. The average length of the Sylvian fissure stem is about 39 mm.[1][6][7][8]

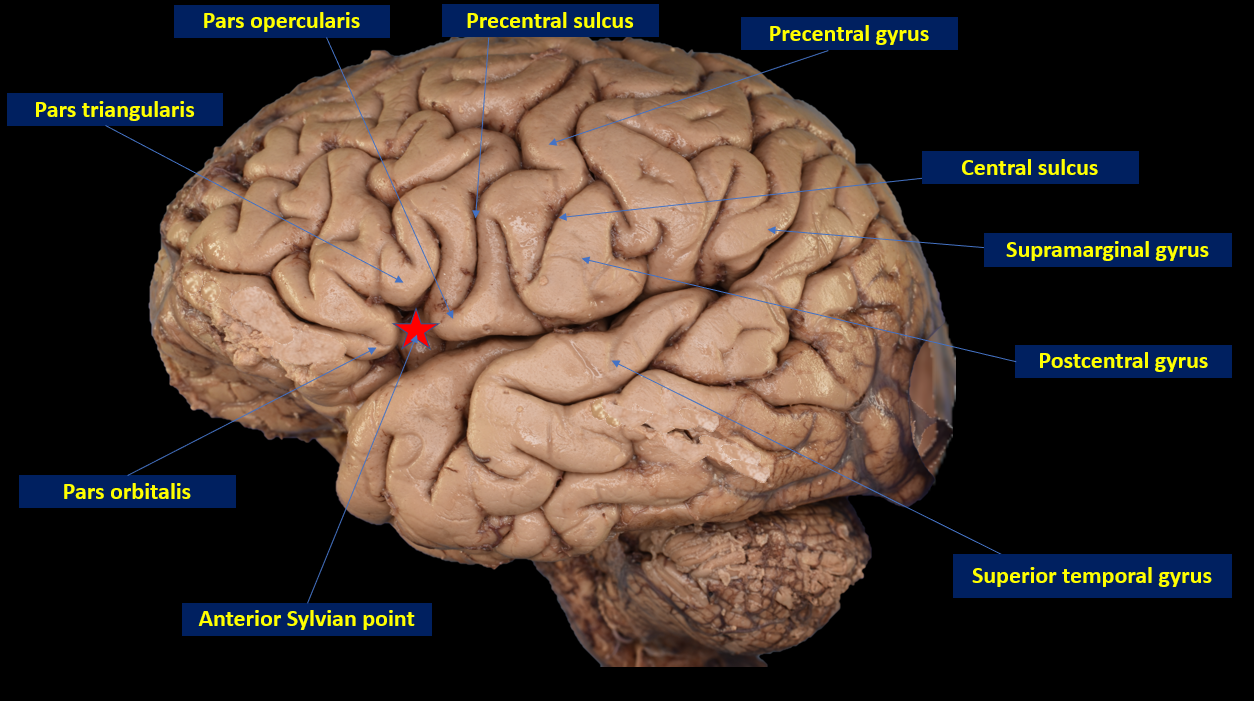

The Sylvian fissure stem is divided into three rami as it reaches the lateral surface of the brain, the anterior horizontal ramus, the anterior ascending ramus, and the posterior ramus. The first two rami divide the inferior frontal gyri on the lateral surface of the frontal lobe into three regions from anterior to posterior: pars orbitalis, pars triangularis, and pars opercularis. The posterior ramus is directed posteriorly and superiorly. It is the posterior continuation of the fissure, separating the frontoparietal operculum above from the temporal operculum below. The posterior ramus ends in the inferior parietal lobule, wrapped around by the supramarginal gyrus. The average length of the posterior ramus is 75 mm.[1][7]

Deep Part

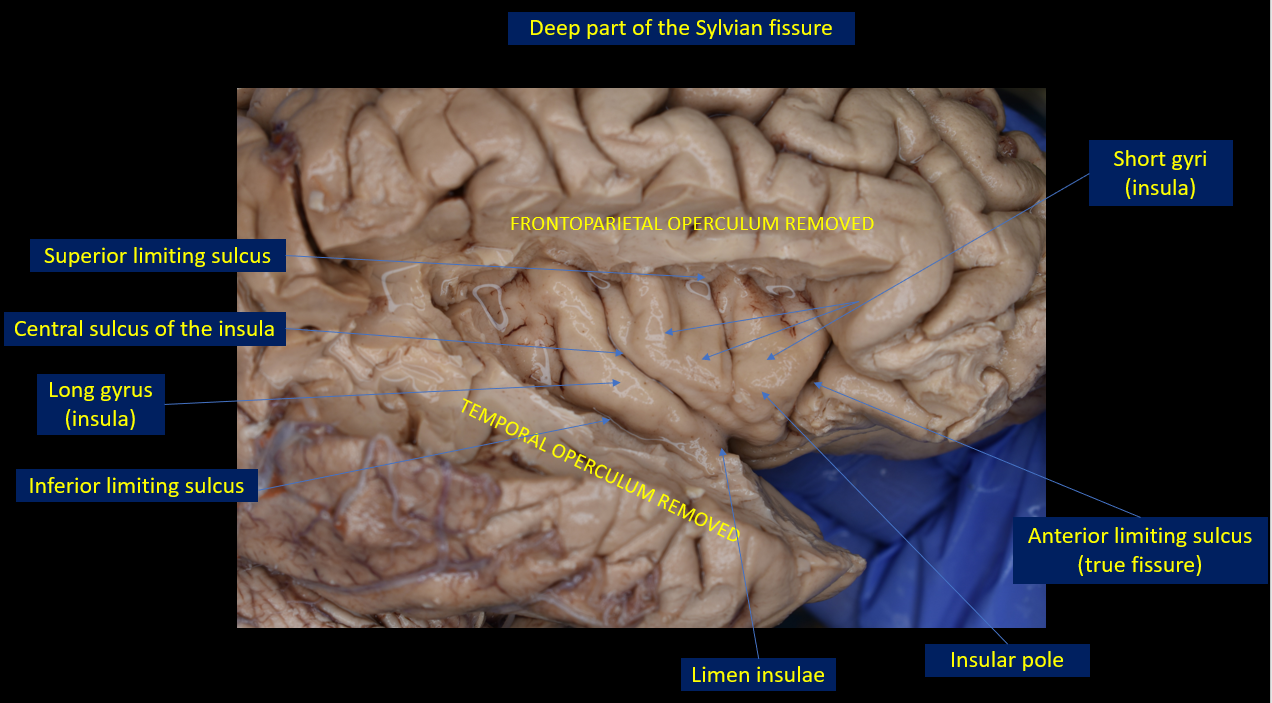

The deep part of the Sylvian fissure, also known as cisternal, can be divided into two compartments: anterior or sphenoidal and posterior or operculoinsular. The sphenoidal compartment has a roof formed by the anterior perforated substance and the posterior region of the basal surface of the frontal lobe, and a floor formed by the anterior region of the planum polare. The limen insulae, the prominence of the uncinate fasciculus on the anteroinferior region of the insula, is located at the lateral border of the compartment.

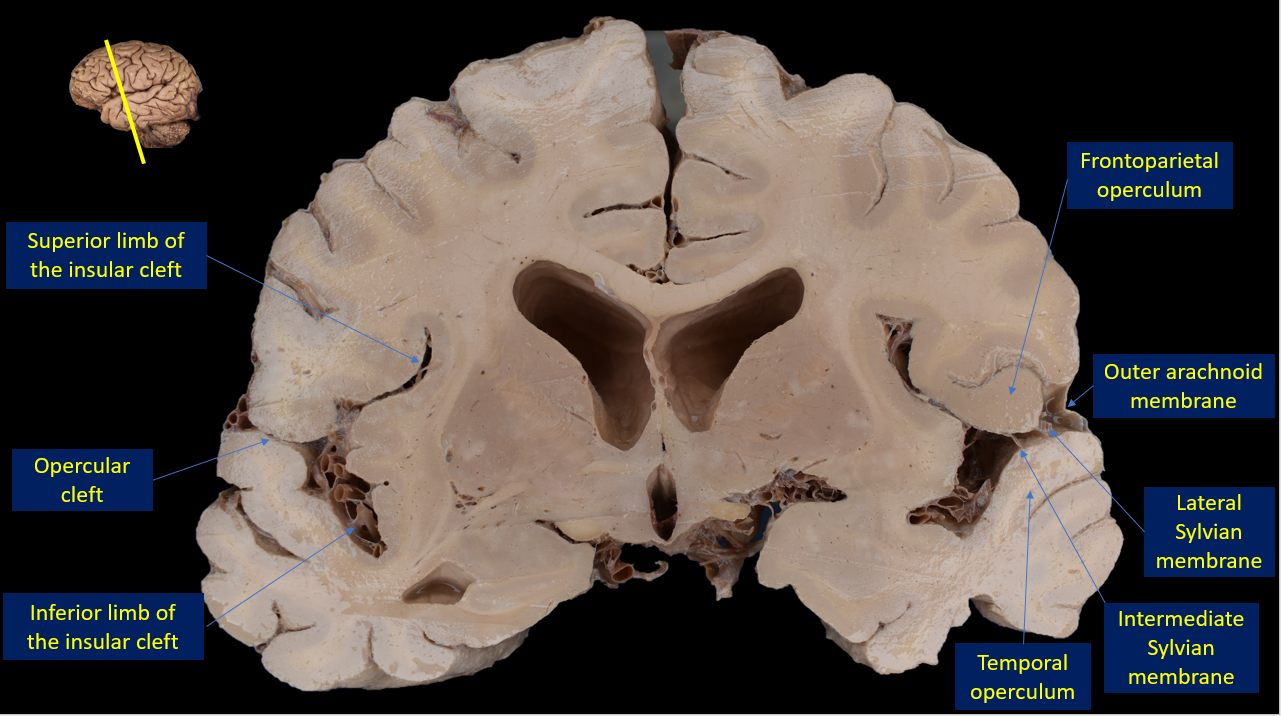

The Sylvian vallecula is the tubular opening that communicates the sphenoidal compartment medially with the subarachnoid spaces around the carotid artery and the optic nerve. Through the Sylvian vallecula, the middle cerebral artery (M1 segment) enters the sphenoidal compartment. The operculoinsular compartment is formed by the opercular and insular clefts. The former is located between the temporal and the frontoparietal opercula, which form the lower and upper lips, respectively, of the opercular compartment. The latter is the space between the opercula and the insula. It is divided into two limbs, superior and inferior. The superior limb is located between the frontoparietal operculum and the insula, and the inferior limb is located between the temporal operculum and the insula (Figs. 3 and 4).[1][5]

Temporal Lobe - Sylvian Fissure

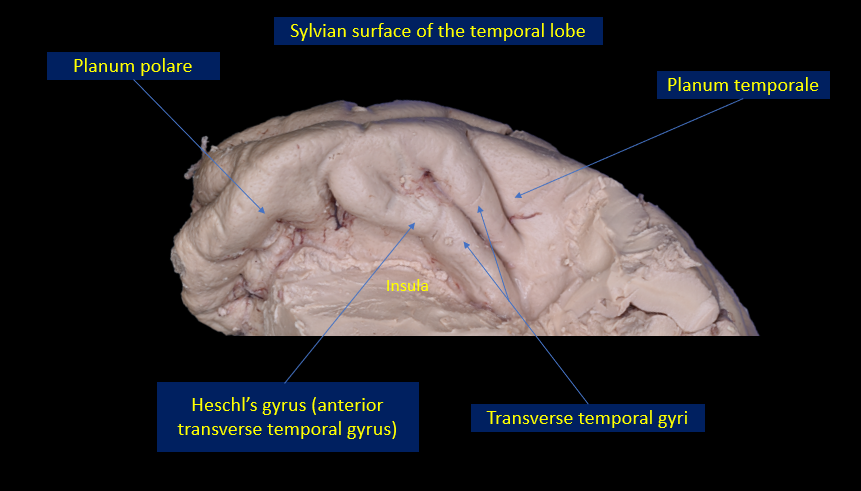

The temporal lobe has four surfaces medial, inferior, lateral, and Sylvian. The superior temporal gyrus that overlies the insula forms the temporal operculum and is located inferiorly to the posterior ramus of the Sylvian fissure (Fig. 2). The Sylvian surface of the temporal lobe constitutes the floor of the deep part of the fissure (Fig. 5). It forms the lower lip of the opercular cleft laterally, the inferior limb of the insular cleft medially, and the floor of the sphenoidal compartment anteromedially.

The anterior area of the Sylvian surface is formed by the planum polare, a smooth area without gyri near the temporal pole. The posterior region is the planum temporale, a triangular region composed of the transverse temporal gyri. The longest and most anteriorly located transverse temporal gyrus is the Heschl's gyrus (Brodmann area 41), a medial extension of the Wernicke area. The Heschl's gyrus and the adjacent cerebral cortex form the primary auditory cortex. The postcentral gyrus is "sitting" just above the Heschl's gyrus in the Sylvian fissure, an important orientation landmark.[1][9]

Wernicke’s language area is located in the dominant hemisphere, on the posterior third of the superior temporal gyrus (Brodmann area 22) and supramarginal gyrus (Brodmann area 40), in close relationship with the temporal and parietal opercula. This area is part of the posterior language system, and its major function is the support of phonologic retrieval, a component of speech production. Lesion of the Wernicke area produces phonemic paraphasia and anomia.[10]

Frontal Lobe - Sylvian Fissure

The frontal lobe has four surfaces lateral, medial, basal, and Sylvian. On the lateral surface, the inferior frontal gyrus is divided into pars orbitalis, pars triangularis, and pars opercularis by the anterior horizontal and anterior ascending rami of the Sylvian fissure (superficial part). The pars triangularis and the pars opercularis of the inferior frontal gyrus and the lower portion of the precentral gyrus constitute the frontal part of the frontoparietal operculum (Fig. 2). The pars orbitalis of the inferior frontal gyrus with the posterior part of the lateral orbital gyrus and the posterior orbital gyrus from the fronto-orbital operculum.

The fronto-orbital operculum covers the anterior surface of the insula. In most brains, the lower precentral gyrus connects with, the lower postcentral gyrus of the parietal lobe via the subcentral gyrus. The subcentral gyrus (pli de passage) interrupts the central sulcus at its lower end, forming the rolandic operculum, part of the frontoparietal operculum just behind the pars opercularis. The Sylvian surface of the frontal lobe is located in the deep part of the Sylvian fissure. It forms the upper lip of the opercular cleft laterally and the upper limb of the insular cleft medially. The posterior region of the basal surface of the frontal lobe, with the anterior perforated substance, forms the roof of the sphenoidal compartment of the Sylvian fissure.[1][7]

Broca’s language area is located in the pars opercularis (Brodmann area 44) and pars triangularis (Brodmann area 45) of the inferior frontal gyrus in the dominant hemisphere. This area is involved in “word formation.” The precentral gyrus (Brodmann area 4) is the primary motor cortex.[11][9][12]

Parietal Lobe - Sylvian Fissure

The parietal lobe has three surfaces lateral, medial, and Sylvian. The lower postcentral gyrus and the superior part of the supramarginal gyrus form the parietal portion of the frontoparietal operculum (Fig. 2). The Sylvian surface of the parietal lobe forms the upper lip of the opercular cleft laterally and the upper limb of the insular cleft medially. The supramarginal gyrus in most hemispheres wraps around the posterior end of the posterior ramus of the Sylvian fissure.[1][7]

The postcentral gyrus (Brodmann area 3b, 1, and 2) is the primary sensory cortex of the brain. The supramarginal gyrus is part of the posterior language system.[13]

Insula - Sylvian Fissure

The insula is part of the deep compartment of the Sylvian fissure (Fig. 3). It can be divided into an anterior surface and a lateral surface. The anterior insular surface is covered by the pars orbitalis and the posterior surface of the posterior orbital gyrus (fronto-orbital operculum). The space between the anterior insular surface and the posterior orbital gyrus creates a true fissure called the anterior limiting sulcus, which is part of the circular sulcus of the insula. The lateral insular surface is covered superiorly by the frontoparietal operculum (pars orbitalis, pars opercularis, subcentral gyrus, and supramarginal gyrus) and inferiorly by the temporal operculum. The lateral surface of the insula resembles a pyramid with a triangular base. The vertex of this pyramid is oriented anteroinferiorly, at the limen insulae. In addition, the lateral insular surface is divided into anterior and posterior regions by the central sulcus of the insula. [1][7]

Three short gyri (anterior, middle, and posterior short gyri) are typically identified in the anterior region. Two long gyri (anterior and posterior long gyri) are present in the posterior region. The three short gyri of the anterior region converge in the anteroinferior edge of the insula, forming a 2-cm, rounded area called the insular pole between the anterior limiting sulcus and the central insular sulcus.

The insular pole is located lateral to the limen insulae. The long gyri of the posterior insular region arise as a single gyrus near the limen insulae and bifurcate posteriorly into the two long gyri. From the insular pole and directed medially toward the posterior orbital gyri of the basal surface of the frontal lobe is the transverse insular gyrus. Separating the lateral insular surface from the frontoparietal and temporal opercula are the superior limiting sulci and inferior limiting sulci, respectively. The anterior limiting sulcus of the anterior insular surface and the inferior and superior limiting sulci of the lateral insular surface form the circular sulcus of Reil or limiting sulcus of the insula.[6][14][15]

The insular cortex is part of the paralimbic group that connects the limbic cortex and the neocortex. It integrates pain and temperature sensation with visceral sensation and is considered the primary viscerosensory area.[16]

Arachnoid Membranes - Sylvian Fissure

The arachnoid layers cover the Sylvian fissure creating a cisternal space where the cerebrospinal fluid and the vascular structures are located (Fig. 3). The distribution of the arachnoid layers in the fissure creates three compartments (from superficial to deep): superficial opercular, deep opercular, and cisternal. These compartments are limited by two membranes and one plane (from superficial to deep): outer arachnoid membrane, lateral Sylvian membrane, and the operculocisternal plane. The superficial opercular compartment contains the superior Sylvian vein and the distal branches of the middle cerebral artery (M4-M5).

The deep opercular compartment extends from the lateral Sylvian membrane to a parasagittal plane passing by the deepest point of apposition between the temporal and frontoparietal opercula (the operculocisternal plane). This compartment mainly contains the M3 segment of the middle cerebral artery, the intermediate Sylvian membrane, and the proximal Sylvian membrane. The cisternal compartment is located between the operculocisternal plane and the insular cortex and contains the proximal segments of the middle cerebral artery (M1-M2), the medial Sylvian membrane, and the deep middle cerebral vein.[2][17]

Vascular Structures - Sylvian Fissure

Middle Cerebral Artery

The Sylvian fissure has a significant relationship with the middle cerebral artery and its branches. There are four segments of the middle cerebral artery: M1 or sphenoidal segment, M2 or insular segment, M3 or opercular segment, and M4 or cortical segment. The sphenoidal segment (M1) has its origin at the terminal bifurcation of the internal carotid artery, in close relationship with the optic chiasm medially and the anterior perforated substance superiorly. It courses in a lateral direction entering the sphenoidal compartment of the Sylvian fissure through the Sylvian vallecula.

The M1 segment ends at the right-angle bend (genu) of the vessel at the limen insulae and, during its course, presents a bifurcation. The M1 segment is subdivided into two parts: prebifurcation (1 trunk) and postbifurcation (2 to 4 branches). The insular segment (M2) has the origin at the genu, at the limen insulae. It ends at the superior, inferior, and anterior circular sulcus of the insula, where it turns 90 degrees to 180 degrees, becoming the M3 segment. The opercular segment (M3) has its origin at the circular sulcus of the insula. It runs along the opercular cleft and ends at the cortical surface, leaving the Sylvian fissure. The cortical segment (M4) starts when the middle cerebral artery exits the Sylvian fissure.[13][18]

Sylvian and Insular Veins

The Sylvian fissure contains superficial and deep veins. The superficial veins from the superficial Sylvian venous complex, composed of three interconnected systems: the anterior Sylvian venous system, the posterior Sylvian venous system, and the superior Sylvian venous system. The three systems have different drainages (described in table 1). The superficial veins are the biggest challenge for neurosurgeons during the first steps of the Sylvian fissure splitting.[13]

The deep insular veins are found in the deepest region of the fissure, and they converge at the limen insulae to drain to the deep middle cerebral vein. The deep middle cerebral vein runs medially toward the anterior perforated substance, where it joins the anterior cerebral vein, forming the basal vein of Rosenthal (anterior segment).[2][13]

TABLE 1. Venous drainage of the superficial Sylvian venous complex

| Venous System |

Drainage |

| Anterior Sylvian venous system |

Sphenoparietal sinus

Cavernous sinus

Sphenopetrosal sinus

|

| Posterior Sylvian venous system |

Lateral temporal vein

Vein of Labbé

Transverse sinus

|

| Superior Sylvian venous system |

Frontoparietal veins

Vein of Trolard

Superior sagittal sinus

|

Topographic Sulcal Points - Sylvian Fissure

Anterior Sylvian Point

The confluence of the anterior horizontal, anterior ascending, and posterior rami of the superficial part of the Sylvian fissure forms the anterior Sylvian point (Fig. 2). This point is located inferior to the pars triangularis and anterior/inferior to the pars opercularis of the inferior frontal gyrus. It divides the Sylvian fissure into the proximal segment (stem, anterior ramus) and the distal segment (anterior ascending and posterior rami). At this point, the Sylvian fissure is enlarged, giving a cisternal aspect, and therefore, it can be used as a starting point to open the Sylvian fissure.[7][15]

Inferior Rolandic Point

The inferior extremity projection of the central sulcus on the Sylvian fissure is the inferior rolandic point. It is located 2.0 to 2.5 cm posterior to the anterior Sylvian point and corresponds to the anterior boundary of the Heschl's gyrus.[15]

Embryology

The Sylvian fissure can be identified at 12 to 14 weeks of gestation as shallow depression on the lateral surface of the brain. It is formed by the convergence of the frontal, parietal, and temporal lobes over the insula. The difference in the pattern of migration between these four lobules gives origin to the Sylvian fissure. The cells of the insula originate from the pallial/subpallial boundary and migrate around the basal ganglia in an oblique migration pattern. The cells of the frontal, parietal and temporal lobes originate in the ventricular and subventricular zones and migrate in a radial pattern. This radial pattern of migration creates the gyri of the brain.[19][20][21]

Sylvian Fissure - Developmental Milestones

The cerebral cortex development during fetal life has been researched using anatomical and imaging studies (magnetic resonance imaging, sonographic studies). In anatomical studies, the Sylvian fissure has been identified by gestational week 14th as a shallow depression between the frontal and temporal lobes. By the 19th week, the fissure is grooved, creating the Sylvian fossa with a base formed by the insula. By week 18th, the insula appears initially as a conical and smooth-surface region surrounded by the circular sulcus. After gestational weeks 28 to 29, the frontoparietal and temporal opercula start to override the insula. Insular gyri are recognizable by the 34th to 35th weeks. The superior temporal gyrus becomes recognizable by gestational week 23, creating a fissure between the gyrus and the insula (the superior temporal fissure). The Heschl's gyrus appears by week 31st.[22][23][24][25]

Yakovlevian Torque

Early anatomical studies of the development of the Sylvian fissure in fetuses noticed an asymmetry of the superior temporal fissure, with a larger anteroposterior length on the left side.[24] In adult's brains, the left Sylvian fissure tends to be longer and less curved on the left side.[26] The asymmetry could be related to the Yakovlevian anticlockwise torque, a geometric distortion of the brain hemispheres. The Yakovlevian torque, also known as occipital bending or counterclockwise brain torque, was described by Paul Ivan Yakovlev. Recent studies have shown the possible association of this formation with bipolar disorder and handedness.[27][28][29]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The blood supply to the insula and the frontoparietal and temporal opercula comes from the branches of the middle cerebral artery.

Insula - Blood Supply

The insula receives the blood supply mainly from short M2-segment perforating arteries. Some short perforating arteries from the M1 and M3 segments give blood supply to the limen insulae and the circular sulcus of the insula, respectively. Medium and long perforating arteries penetrate the insular cortex to give blood supply to deeper structures, including the extreme capsule, the claustrum, the external capsule, and the corona radiata. Of particular interest during surgical procedures in insular lesions are the long perforating insular arteries. They penetrate the posterosuperior region of the insula to give blood supply to the corona radiata. These arteries must be preserved to avoid infarction of the corona radiata resulting in hemiparesis.[14][30]

Frontoparietal and Temporal Opercula - Blood Supply

The branches of the M4 segment (cortical) of the middle cerebral artery give the blood supply to the perisylvian cortex. The cortical areas supplied by the middle cerebral artery follow a pattern of 12 areas. The inferior part of the pars orbitalis is in the orbitofrontal area. The superior region of the pars orbitalis, the pars triangularis, and the anterior part of the pars opercularis are in the prefrontal area. The posterior part of the pars opercularis and the lower end of the precentral gyrus is in the precentral area. The inferior region of the postcentral gyrus is in the central area. All these areas receive the orbitofrontal, prefrontal, precentral, and central arteries.

The anterior region of the inferior parietal lobule is in the anterior parietal area. The posterior part of the inferior parietal lobule, including the supramarginal gyrus, is in the posterior parietal area. The posterior region of the superior temporal gyrus and part of the supramarginal gyrus is in the angular area. These areas receive the blood supply from the anterior and posterior parietal arteries and the angular artery. The posterior half of the superior temporal gyrus is in the termporo-occipital area. The middle region of the superior temporal gyrus is in the posterior temporal area. The superior temporal gyrus at the level of the pars triangularis and pars opercularis is in the middle temporal area. The anterior region of the superior temporal gyrus is in the anterior temporal area. These areas of the temporal lobe receive 4 or 5 main stem arteries.[13]

Surgical Considerations

Transsylvian Approach

The transsylvian approach through a pterional craniotomy gives access to important neural (insula, basal ganglia, I-III cranial nerves), vascular (middle cerebral artery, proximal anterior cerebral artery, internal carotid artery, upper basilar artery), and cisternal (lamina terminalis, chiasmatic, interpeduncular, carotid, crural) structures. For extra-axial lesions (aneurysms, meningioma, pituitary adenoma, craniopharyngioma), the split of the Sylvian fissure helps to expose the surgical region. For intra-axial lesions in the deep structures to the Sylvian fissure (insular gliomas, basal ganglia gliomas, deep arteriovenous malformations, intracerebral hematomas), a transsylvian-transinsular approach may be useful. The transsylvian-transinsular approach has two main variants anterior and posterior. The anterior transsylvian transinsular approach exposes the lateral head of the caudate nucleus and the anterior limb of the internal capsule. The posterior transsylvian-transinsular approach exposes the wedge of the basal ganglia (lateral to the internal capsule), the claustrum, the extreme capsule, the putamen, and the globus pallidus.[32][33]

Sylvian Fissure Split

The splitting of the Sylvian fissure is one of the most important surgical skills in neurosurgery, and it requires a deep knowledge of neuroanatomy. The "inside-out technique," introduced by Yasargil, is an effective and atraumatic way to open the Sylvian fissure.[2][34][35]

Indications

- Insular tumors

- Middle cerebral artery aneurysms

- Anterior circulation aneurysms

- Basilar aneurysms (distal)

- Anterior skull base tumors

General Principles: use the "inside-out" dissection

Patient's position: supine, head rotated away 30 degrees.

There are three spaces from superficial to deep, with different challenges:

- Superficial opercular compartment:

- Identify the anterior Sylvian point below the pars triangularis of the inferior frontal lobe, the best point to start the dissection.

- Sharp incision of the outer arachnoid membrane, always on the frontal side of the superficial Sylvian veins

- Gentle displacement of the superficial veins to the temporal lobe.

- Dissection of the arachnoid bands that connect brain-brain and vein-vein, exposing the lateral Sylvian membrane.

- Deep opercular compartment:

- Dissection of the lateral Sylvian membrane exposing the deep opercular compartment

- Dissection of the arachnoid bands, mainly brain-brain (intermediate Sylvian membrane is a prominent brain-brain arachnoid band) and artery-brain.

- Cisternal compartment

- Identification of the M2 segment (perpendicular to the surgeon's line of sight) deeply seated on the lateral surface of the insula.

Follow the branches of the middle cerebral artery from distal to proximal gives orientation to the neurosurgeon.

The Sylvian dissection, preservation of the venous anatomy, and its drainage pathways can be largely facilitated by applying the intraoperative indocyanine green (ICG) venography.[36]

Clinical Significance

Heat CT Scan - Sylvian Fissure Signs

Early signs of the middle cerebral artery occlusion in non-contrast head CT scan (<24 hours):

- Hyperdense MCA (middle cerebral artery) sign: the appearance of increased attenuation of the M1 segment of the middle cerebral artery.[37]

- MCA (middle cerebral artery) dot sign: hyperdensity in the distal middle cerebral artery and its branches inside the Sylvian fissure.[38]

Brain MRI - Sylvian Fissure Signs

"Bat-wings" appearance: bilateral open Sylvian fissures typically seen in type I glutaric aciduria.[39]

Angiography

The different segments of the middle cerebral artery can be identified in cerebral angiography. At the limen insulae, the M1 segment becomes the M2 segment, at the genu, and turns around the insular pole. The M1 segment runs horizontally (horizontal segment) and could or could not include the main bifurcation. When the bifurcation is present in the horizontal segment it is divided into pre-bifurcation and post-bifurcation M1. The middle cerebral artery bifurcation can be classified as "classic" when it occurs at the genu or "non-classic" when it occurs before the genu.[5][40]

The M2 segment starts at the genu, at the limen insulae, and has a vertical course (vertical segment). Immediately medial to the M2 segment is located the lateral surface of the insula. The M2 segment forms several loops when it reaches the superior limiting sulcus of the insula, becoming the M3 segment. The first loop of M2 is more medially located in the angiography because it takes place in the anterior insular cleft. The last loop of the M3 segment, over the temporal operculum exiting the Sylvian fissure, is a relevant angiographic landmark: the M point or angiographic Sylvian point. The angiographic Sylvian point is the point where the angular branch leaves the insula posteriorly and turns inferolaterally to reach the brain's surface. This point represents the posterior limit of the Sylvian fissure and typically is located 3.0 to 4.6 cm medially from the inner table of the skull (on anteroposterior view) and in the middle point of the clinoparietal line (on the lateral view).[6][41]

The Sylvian triangle is an important landmark on the lateral cerebral angiograms. It is formed by three lines: a straight line that follows the tops of the insular loops of the M2 segment superiorly, the major trunk of the middle cerebral artery anteriorly, and the first ascending insular branch of the M2 segment posteriorly. The angiographic Sylvian point is the most medial point of the highest loop of the Sylvian triangle (superior line of the triangle) on the anteroposterior projection. In the past, the Sylvian triangle was the most important vascular configuration to diagnose and localize space-occupying lesions in the supratentorial space.[42]

Middle Cerebral Artery Aneurysms

The middle cerebral artery is the third most common location of the intracranial saccular aneurysms (22%). Most of them arise from the bifurcation or trifurcation of the M1 segment, located in the Sylvian fissure's sphenoidal compartment.[43][44]

The classification by size for the middle cerebral artery aneurysms is shown below (Table 2).

Different treatment strategies for management include transluminal embolization techniques, microsurgical techniques, or hybrid techniques (table 3).[45]

Coil or clip? General Principles [45][46][47]

- Microsurgical and embolization techniques complement each other

- Microsurgical clipping is particularly effective for the middle cerebral artery aneurysms

- Patient's age and comorbidities:

- ruptured aneurysms in young patients may be a better candidate for microsurgical clipping

- ruptured aneurysms in elderly patients with comorbidities, maybe a better candidate for embolization techniques

- Middle cerebral artery aneurysms with wide necks and/or perforating branches associated (dome or base) can be approached safer with surgery and clip reconstruction than embolization.

- Ruptured aneurysms with mass effect due to intracerebral hematoma are better candidates for open surgery.

- Experience and preferences of the surgeon

- Patient's preference

- Costs and accessibility

Table 2. Classification of the middle cerebral artery aneurysms according to the seize

| Category |

Size |

| Small |

<5 mm |

| Medium |

5-10 mm |

| Large |

11-25 mm |

| Giant |

> 25 mm |

Table 3. Strategies in the management of intracranial aneurysms

| Transluminal embolization techniques |

Microsurgical techniques |

Hybrid techniques (combination of microsurgery and endovascular) |

| Simple coiling |

Microsurgical clipping |

Microsurgical treatment post-endovascular therapy |

| Ballon-assisted coiling |

Bypass technique |

Endovascular therapy post-microsurgical treatment |

| Stent-assisted coiling |

|

|

| Double microcatheter technique |

|

|

| Flow diverters |

|

|

| Intrasaccular flow disruptor |

|

|

Sylvian Fissure Arachnoid Cysts

The arachnoid cysts represent less than 1% of the intracranial lesions. They are benign cystic lesions that can be located along the neuroaxis. The Sylvian fissure is the most common location; these are called middle cranial fossa arachnoid cysts (34%). They are predominant in male patients and on the left side. The pathophysiology is not clear, but some authors consider arachnoid cysts as congenital lesions.[48][49]

Most of these cysts are found incidentally during brain images. In symptomatic patients, usually larger cysts, the most common symptoms include headache, seizures, and motor deficit. Rarely, the Sylvian cysts can be localized bilaterally, and there is an association of bilateral cysts with glutaric aciduria type I (GA-I).[50] Familial middle cranial fossa arachnoid cysts have also been reported.[51]

According to the size of the Sylvian arachnoid cysts, they can be classified into three categories I-III (table 2).[52]

The management of the arachnoid cysts includes conservative and surgical alternatives. Conservative management is preferred in asymptomatic patients with small cysts and includes a follow-up brain imaging 6-8 months after the initial image to rule out the enlargement of the cyst. Surgical techniques include endoscopic, microsurgical (craniotomy), and shunting. The surgical approach is indicated in symptomatic patients and/or large cysts with mass effect. A metanalysis suggests the middle cranial fossa arachnoid cysts. Neuroendoscopic fenestration is the best initial procedure.[53] Postoperative complications in Gelassi type I and type II decompression have been described, including subdural hematomas or hygromas.

Table 4. Galassi's classification of the middle cranial fossa arachnoid cysts (based on CT scan and CT cisternography)

| Arachnoid cyst type |

Radiologic Characteristics |

CT-cisternogram (communication with subarachnoid space) |

| Type I |

A small lesion, spindle-shaped, limited to the anterior aspect of the temporal fossa.

Lack of mass effect, no distortion of the ventricles, no displacement of the midline structures.

|

Communicates with subarachnoid space |

| Type II |

A medium-sized lesion, quadrangular shape in at least one CT-scan' slice, straight inner margin

Occupies the anterior and middle part of the temporal fossa and extends superiorly along the Sylvian fissure (proximal and intermediate segments), which is widely open.

|

Communicates partially with subarachnoid space |

| Type III |

A large lesion, oval or round in shape, involves the entire Sylvian fissure; midline structures are displaced.

The atrophic temporal lobe, with compression of the frontal and parietal lobes, middle cranial fossa extension.

|

Minimal communication |