Continuing Education Activity

Imaging plays an important role in the diagnosis and management of trauma to the eye. In addition to computed tomography, which is the primary imaging modality used for orbital trauma, ultrasound and optical coherence tomography are less-invasive techniques to assess the structures of the eye. This activity reviews the imaging techniques used in the setting of trauma to the eye and orbit. It describes the key findings for various vision and life-threatening conditions, including orbital fractures, foreign bodies, open-globe injuries, retinal detachment, and anterior-segment injuries.

Objectives:

- Describe the imaging techniques indicated for various settings of trauma to the eye and orbit.

- Review the anatomy of the eye and orbit, focusing on the most commonly implicated structures in orbital trauma.

- Summarize key findings that may be seen on imaging in patients with a history of orbital and ocular trauma.

- Explain the appropriateness of imaging techniques used by the interprofessional team in various situations, such as ocular foreign body and open-globe injuries.

Introduction

Trauma to the eye makes up 3% of all emergency department visits in the United States.[1] Imaging plays a key role in medical diagnostics, decision-making, and treatment planning for ocular trauma. The use of imaging for eye complaints in the emergency setting has increased significantly over the past two decades.[2][3]

Knowing when to order a test and how to interpret the results is important for patient outcomes and cost-effectiveness. This article will discuss the anatomy of the eye and orbit, common imaging modalities used to assess the relevant structures, findings of commonly seen pathology, and the indications and reasoning behind each test.

Anatomy

The orbit is a pyramid-shaped space formed by seven bones. The orbital roof consists of the frontal bone and the lesser wing of the sphenoid bone. The lateral wall of the orbit consists of the zygomatic bone and the greater wing of the sphenoid bone. The floor consists of the maxillary, palatine, and zygomatic bones. The medial wall consists of the ethmoid, maxillary, lacrimal bones, and the lesser wing of the sphenoid bone. The medial and inferior orbital walls are thinnest and most prone to fracture following trauma to the face.

The globe is located in the anterior orbit. The outer shell of the globe consists of the sclera posteriorly and cornea anteriorly. Within the outer shell lies the uveal tract, which includes the ciliary body and choroid. The innermost layer is the neurosensory retina, which may become detached following trauma.

The lens is suspended by zonules connected to the ciliary body and divides the globe into the anterior and posterior segments. Traumatic violation of the lens zonules may cause dislocation of the lens. The iris and pupil are anterior to the lens and subdivide the anterior segment into the anterior and posterior chambers, which are both filled with aqueous humor. Posterior to the lens is a large cavity filled with vitreous humor.

Attached to the sclera exteriorly are the six extra-ocular muscles responsible for eye movement. Four of the six muscles originate at the orbital apex and attach to the sclera 5.5 to 7.5 millimeters behind the edge of the cornea forming a cone-like structure. Within this cone are blood vessels, lymphatics, fat, and the optic nerve sheath, which contains the optic nerve and the ophthalmic artery. The apex of the cone is a crowded space where many nerves and blood vessels pass through small fissures and foramina. Fractures or hematomas in this area may damage these structures, which is important to assess on imaging. The vital structure for vision is the optic nerve, which consists of the axons of cells that transmit visual input received by the retina. Damage to the optic nerve may lead to permanent vision loss.

Plain Films

Plain x-ray films can identify orbital fractures as well as radiopaque intraocular or intraorbital foreign bodies. They are sometimes used to screen for a metallic foreign body prior to MRI imaging. However, plain films are rarely performed in cases of acute ocular trauma, as CT is the imaging modality of choice.

Computed Tomography

Computed tomography (CT) is the primary imaging modality used for the evaluation of ocular trauma. It allows for three-dimensional viewing of the orbital bones, soft tissue, and ocular structures and is useful for assessing a wide variety of trauma-related pathology. Radiographic cuts through the orbits should be less than <3mm (typically 0.5mm-2mm). In cases of suspected traumatic optic neuropathy or the presence of a foreign body, 1-millimeter cuts should be performed.

Orbital Fractures

CT is the modality of choice for accurately detecting fractures of the orbit and their associated soft-tissue injuries. The medial and inferior orbital walls are the thinnest and most prone to fracture; however, all orbital bones are susceptible to fracture following blunt or penetrating injury.

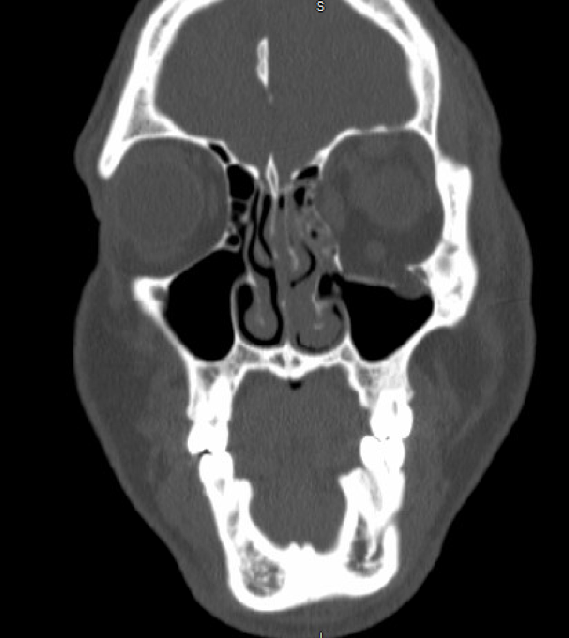

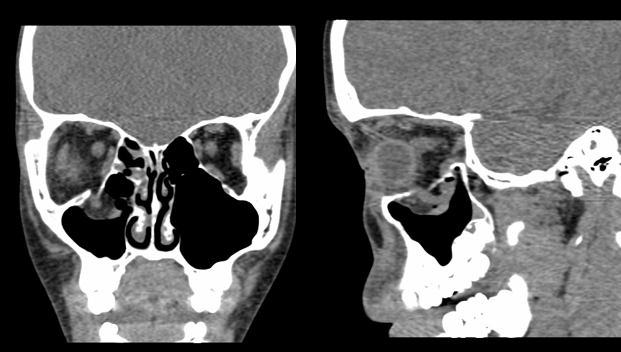

Blow-out fractures are common and occur when blunt trauma causes increased pressure within the orbit, leading to herniation of orbital contents out of the orbit and into the adjacent sinus (Fig 1). CT can easily identify the bones involved, the projection of any bony fragments, and the degree of extraocular muscle displacement or injury. Hemorrhage may be visualized in the adjacent sinus, and emphysema of the orbit and eyelids can occur. Enophthalmos occurs when the globe retracts into orbit due to its increased volume. Surgical repair may be indicated for fractures leading to enophthalmos of greater than 2mm, or those that involve greater than 50% of the orbital floor. Still, cases treated with observation alone have also shown good results.[4]

Muscle entrapment is a surgical emergency if it leads to bradycardia due to the oculocardiac reflex. This typically occurs in pediatric patients with a “trap door” fracture, in which the flexible bone springs back into place after an injury resulting in impingement of muscle fibers. Signs of entrapment are best visualized on sagittal and coronal sections. They include rounding of the muscle shape and displacement of the muscle through a small fracture site into the adjacent sinus (Fig 2).[5] Clinically, the patient may have normal appearing eyes without signs of injury, termed a “white-eye blowout fracture.” Other clinical signs of entrapment include diplopia, bradycardia, nausea, and vomiting. Immediate repair is indicated in these cases.

Orbital roof fractures are associated with pneumocephalus, intracranial hematoma, cerebrospinal fluid leaks, and violation of the dura. Neurosurgical evaluation is indicated in these cases.[5]

Retrobulbar Hemorrhage and Orbital Compartment Syndrome

A retrobulbar hemorrhage or hematoma can occur following ocular trauma and refers to a collection of blood within the orbit. Typically, retrobulbar hematomas are small and not significant clinically; however, larger hemorrhages can result in an orbital compartment syndrome due to increased pressure within the confined space of the orbit. Clinically it is characterized by elevated intraocular pressure, the presence of an afferent pupillary defect, proptosis, resistance to retropulsion, and decreased visual acuity. Once diagnosed, urgent decompression by lateral canthotomy and cantholysis is indicated to prevent permanent vision loss. CT scan is used to identify hematomas in orbit, and collections of blood are often visualized adjacent to bony fractures (Fig 3). Signs of orbital compartment syndrome on CT include proptosis, stretching of the optic nerve, and tenting of the posterior globe contour (Fig 4), but these findings must always be correlated clinically.

Foreign Bodies

CT is the modality of choice for detecting intraocular or orbital foreign bodies (Fig 5). The most common inorganic foreign bodies associated with ocular injury are glass and metals. Organic materials such as wood are difficult to detect on CT, but some clues to their presence include an inflammatory reaction surrounding the foreign body, which may be seen on imaging.[4]

Open Globe Injury

CT scans are routinely obtained for detecting open-globe injuries. CT findings that suggest open-globe injury include a change in the globe contour (Fig 6), intraocular air and blood presence, and intraocular foreign bodies. If the perforation is posterior, a deep anterior chamber may be seen, resulting from a decrease in volume of the vitreous cavity and the lens moving posteriorly. Vitreous hemorrhage and choroidal or retinal detachment may also be seen (Fig 7). It is important to note that air in the globe can also be caused by prior eye surgery, so findings must be correlated clinically.[6] Open globe injuries are ophthalmic emergencies requiring surgical repair within 24 hours.

Though CT is commonly ordered to detect a ruptured globe, the reported sensitivities are 56 to 68%. Positive predictive values ranged from 86-100%, but negative predictive values ranged from 42% to 50%.[2] A study involving 125 cases of open globe injury found that imaging results do not influence the management decisions of these patients.[7] Thus, obtaining prompt ophthalmologic consultation is necessary, in addition to imaging when there is suspicion for globe rupture.

Anterior Segment Injuries

Lens dislocation can be visualized on CT images (Fig 8). Trauma accounts for more than half of all cases of lens dislocation. The lens may be displaced forward into the anterior chamber, backward into the posterior segment, or its position may just be altered slightly if only some of the zonules are broken. Clinically, the examiner may observe phacodenesis, or tremulousness of the lens with eye movement, during a slit lamp exam. A bilateral dislocation should raise concern for a systemic condition such as Marfan syndrome or homocystinuria.[6]

A hyphema, or blood in the anterior chamber, can be visualized on CT as increased attenuation within the anterior chamber.[5]

Detachments of the Retina/Choroid

Retinal detachments can occur after blunt or penetrating injury and may be seen on CT imaging as a thin, V-shaped hyperattenuating within the globe. The apex of the “V” is usually attached to the optic disk and the extremities attached anteriorly to the ora serrata. CT may also show choroidal detachments, which result from fluid accumulating in the space between the choroid and sclera. This can look like two thin convexities curving into the vitreous cavity, which may or may not be touching one another (“kissing choroidals”). Choroidal detachments are often a result of ocular hypotony, which can arise after ocular surgery.[6] It is important to note that although retinal and choroidal detachments are often incidentally visualized on CT, B-scan ultrasonography is the imaging modality used to diagnose these conditions accurately.

Magnetic Resonance

MRI is not frequently used in the setting of ocular trauma and is contraindicated when there is suspicion of a metallic foreign body. MRI may provide a more detailed view of muscle injuries or inorganic foreign bodies; however, CT is the primary imaging modality in all cases of ocular trauma.[4]

Ultrasonography

Ultrasound imaging is a quick, non-invasive, and cost-effective imaging technique to assess the eye. It is routinely used to assess intraocular structures when the ocular media is not clear for fundus examination, as in the case of a vitreous hemorrhage or hyphema. It may also be used in cases of suspected retinal pathology; if, for example, a patient complains of flashes, floaters, or curtains. Pathological processes that may be visualized using ultrasonography include vitreous hemorrhage, retinal detachment, intraocular foreign bodies, damage to the extra-ocular muscles, and scleral rupture. Ultrasound should be used cautiously if a ruptured globe is suspected and is typically deferred if a ruptured globe is confirmed.

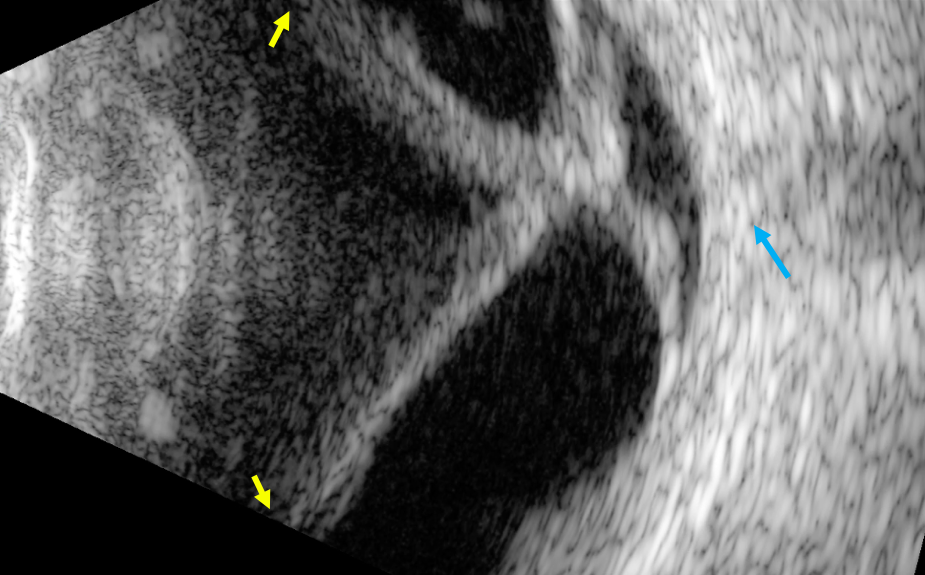

Retinal Detachment

Detachments of the retina may occur spontaneously or after blunt trauma to the eye. Clinical history that raises suspicion for the presence of a retinal detachment is sudden onset flashing lights in the vision or a curtain over the vision. A retinal detachment on ultrasound imaging appears as a bright, continuous, free-floating membrane within the vitreous (Fig 9). Total, or “funnel,” retinal detachments may have a triangular shape with attachments at the optic disc and the ora serrata. Multiple prospective and retrospective studies have shown that point-of-care ultrasound of the eye performed by emergency physicians can accurately detect retinal detachments in the emergency room setting.[8] It is a helpful triaging tool for differentiating patients who need emergent ophthalmologic consultation from those who may be seen as an outpatient. A detachment found on an ultrasound scan warrants emergent ophthalmology consultation to assess the extent of the detachment. For certain types of retinal detachments, urgent surgery is necessary to preserve vision.

Carotid Cavernous Fistulas

Carotid cavernous fistulas are defined as an abnormal connection between the carotid artery and branches of the cavernous sinus, leading to reverse blood flow. It is usually a result of trauma, though some cases can be spontaneous. Clinically, patients may have symptoms of proptosis and diplopia. A dilated superior ophthalmic vein is best visualized on CT angiography, but this finding may also be seen on ultrasound as an anechoic superior orbital mass. Color Doppler may show high-velocity turbulent flow within the mass.[4]

Angiography

CTA is helpful for diagnosing intracranial vascular pathology, including an aneurysm. In the context of ocular trauma, it is most useful for detecting carotid-cavernous fistulas, described in the previous section under “Ultrasonography.” On unenhanced CT imaging, a dilated superior ophthalmic vein, enlarged cavernous sinus, and enlarged extraocular muscles may be seen. The diagnosis is confirmed by directly visualizing the fistula on CT angiography.

Anterior Segment Optical Coherence Tomography

Anterior segment optical coherence tomography (ASOCT) is a non-invasive imaging technique used to visualize cross-sections of the cornea, anterior chamber, iris, and ciliary body. Because it does not require any patient contact, it is an ideal way to assess the anterior chamber and iridocorneal angle in cases of blunt trauma to the eye. While gonioscopy remains the gold standard for visualization of the angle, its use is generally deferred for acute cases of hyphema to prevent rebleeding. Furthermore, while gonioscopy requires a clear cornea, ASOCT can be used even when the cornea is hazy or edematous. Thus, ASOCT has become a valuable tool in both trauma and routine cases.

Cyclodialysis Cleft

A cyclodialysis cleft is defined as a separation of the longitudinal ciliary muscle fibers from the scleral spur, leading to increased aqueous outflow and may result in ocular hypotony. This separation can be visualized on ASOCT, which identifies the exact location and the extent of the disinsertion.[9] The images are high-resolution and are helpful for surgical planning. There should be raised suspicion for a cyclodialysis cleft in any patient with a measured intraocular pressure of 5mmHg or below after surgery or blunt trauma. There may be other clinical signs present as well, such as a hyphema or tears in the iris.

Patient Positioning

For CT and MRI imaging, patients should lie in a supine position on the CT table with the patient’s head in the head holder. Patients should remain as immobile as possible during the study to prevent motion artifacts. Contrast is useful for visualizing the extraocular muscles and vascular structures.

During ultrasonography of the eye, the patient should be sitting as comfortably as possible and upright in the examination chair. The patient’s head should be resting on the headrest, and eyes should be closed. There should be a layer of methylcellulose gel between the probe and the eyelid. During the dynamic examination, while the probe is placed over the eyelid, the patient will gaze upward, downward, left, and right as directed by the examiner. The patient’s head should remain still during the entire exam.

For ASOCT, the patient should be sitting upright in an examination chair. The chair height should be adjusted so that the patient’s chin comfortably rests in the chinrest of the machine. The patient should open both eyes and look forward towards the target light either inside the camera or on an external light source. For the best quality images, the patient should not move and should open the eyes completely between normal blinking.

Clinical Significance

Imaging has become an essential tool in the management of patients with ocular trauma. The use of CT imaging increased from 3 million scans in 1980 to more than 60 million in 2005. The use of MRI nearly tripled between 1997 and 2006. There are now many different imaging modalities available, and each has its advantages. While CT is traditionally the imaging modality of choice for most cases of ocular trauma, it is important to be aware of the newer and less invasive modalities such as ultrasound and ASOCT. Overuse of imaging can be harmful, leading to unnecessary radiation exposure, incidentalomas, patient anxiety, increased length of stay in the emergency room, and waste resources.[10]

For both the emergency physician and the ophthalmologist, it is important to understand the indications for each imaging study and to be able to communicate them to the radiologist. Several ocular emergencies require urgent intervention, and imaging plays a key part in the medical decision-making process. Streamlined and efficient use of imaging can be vision and life-saving.