[1]

Crutch SJ,Lehmann M,Schott JM,Rabinovici GD,Rossor MN,Fox NC, Posterior cortical atrophy. The Lancet. Neurology. 2012 Feb;

[PubMed PMID: 22265212]

[3]

Mendez MF,Ghajarania M,Perryman KM, Posterior cortical atrophy: clinical characteristics and differences compared to Alzheimer's disease. Dementia and geriatric cognitive disorders. 2002;

[PubMed PMID: 12053130]

[4]

Galton CJ,Patterson K,Xuereb JH,Hodges JR, Atypical and typical presentations of Alzheimer's disease: a clinical, neuropsychological, neuroimaging and pathological study of 13 cases. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2000 Mar;

[PubMed PMID: 10686172]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[5]

Yerstein O,Parand L,Liang LJ,Isaac A,Mendez MF, Benson's Disease or Posterior Cortical Atrophy, Revisited. Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD. 2021;

[PubMed PMID: 34057092]

[6]

Crutch SJ,Schott JM,Rabinovici GD,Murray M,Snowden JS,van der Flier WM,Dickerson BC,Vandenberghe R,Ahmed S,Bak TH,Boeve BF,Butler C,Cappa SF,Ceccaldi M,de Souza LC,Dubois B,Felician O,Galasko D,Graff-Radford J,Graff-Radford NR,Hof PR,Krolak-Salmon P,Lehmann M,Magnin E,Mendez MF,Nestor PJ,Onyike CU,Pelak VS,Pijnenburg Y,Primativo S,Rossor MN,Ryan NS,Scheltens P,Shakespeare TJ,Suárez González A,Tang-Wai DF,Yong KXX,Carrillo M,Fox NC,Alzheimer's Association ISTAART Atypical Alzheimer's Disease and Associated Syndromes Professional Interest Area., Consensus classification of posterior cortical atrophy. Alzheimer's

[PubMed PMID: 28259709]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[7]

Schott JM,Crutch SJ,Carrasquillo MM,Uphill J,Shakespeare TJ,Ryan NS,Yong KX,Lehmann M,Ertekin-Taner N,Graff-Radford NR,Boeve BF,Murray ME,Khan QU,Petersen RC,Dickson DW,Knopman DS,Rabinovici GD,Miller BL,González AS,Gil-Néciga E,Snowden JS,Harris J,Pickering-Brown SM,Louwersheimer E,van der Flier WM,Scheltens P,Pijnenburg YA,Galasko D,Sarazin M,Dubois B,Magnin E,Galimberti D,Scarpini E,Cappa SF,Hodges JR,Halliday GM,Bartley L,Carrillo MC,Bras JT,Hardy J,Rossor MN,Collinge J,Fox NC,Mead S, Genetic risk factors for the posterior cortical atrophy variant of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's

[PubMed PMID: 26993346]

[8]

Snowden JS,Stopford CL,Julien CL,Thompson JC,Davidson Y,Gibbons L,Pritchard A,Lendon CL,Richardson AM,Varma A,Neary D,Mann D, Cognitive phenotypes in Alzheimer's disease and genetic risk. Cortex; a journal devoted to the study of the nervous system and behavior. 2007 Oct;

[PubMed PMID: 17941342]

[9]

Koedam EL,Lauffer V,van der Vlies AE,van der Flier WM,Scheltens P,Pijnenburg YA, Early-versus late-onset Alzheimer's disease: more than age alone. Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD. 2010;

[PubMed PMID: 20061618]

[10]

Renner JA,Burns JM,Hou CE,McKeel DW Jr,Storandt M,Morris JC, Progressive posterior cortical dysfunction: a clinicopathologic series. Neurology. 2004 Oct 12;

[PubMed PMID: 15477534]

[11]

Hof PR,Vogt BA,Bouras C,Morrison JH, Atypical form of Alzheimer's disease with prominent posterior cortical atrophy: a review of lesion distribution and circuit disconnection in cortical visual pathways. Vision research. 1997 Dec;

[PubMed PMID: 9425534]

[12]

Levine DN,Lee JM,Fisher CM, The visual variant of Alzheimer's disease: a clinicopathologic case study. Neurology. 1993 Feb;

[PubMed PMID: 8437694]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[13]

Tang-Wai DF,Graff-Radford NR,Boeve BF,Dickson DW,Parisi JE,Crook R,Caselli RJ,Knopman DS,Petersen RC, Clinical, genetic, and neuropathologic characteristics of posterior cortical atrophy. Neurology. 2004 Oct 12;

[PubMed PMID: 15477533]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[14]

Seguin J,Formaglio M,Perret-Liaudet A,Quadrio I,Tholance Y,Rouaud O,Thomas-Anterion C,Croisile B,Mollion H,Moreaud O,Salzmann M,Dorey A,Bataillard M,Coste MH,Vighetto A,Krolak-Salmon P, CSF biomarkers in posterior cortical atrophy. Neurology. 2011 May 24;

[PubMed PMID: 21525425]

[15]

McMonagle P,Deering F,Berliner Y,Kertesz A, The cognitive profile of posterior cortical atrophy. Neurology. 2006 Feb 14;

[PubMed PMID: 16476930]

[17]

Beh SC,Muthusamy B,Calabresi P,Hart J,Zee D,Patel V,Frohman E, Hiding in plain sight: a closer look at posterior cortical atrophy. Practical neurology. 2015 Feb

[PubMed PMID: 25216669]

[18]

Pelak VS,Smyth SF,Boyer PJ,Filley CM, Computerized visual field defects in posterior cortical atrophy. Neurology. 2011 Dec 13;

[PubMed PMID: 22131540]

[19]

Lehmann M,Crutch SJ,Ridgway GR,Ridha BH,Barnes J,Warrington EK,Rossor MN,Fox NC, Cortical thickness and voxel-based morphometry in posterior cortical atrophy and typical Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiology of aging. 2011 Aug;

[PubMed PMID: 19781814]

[20]

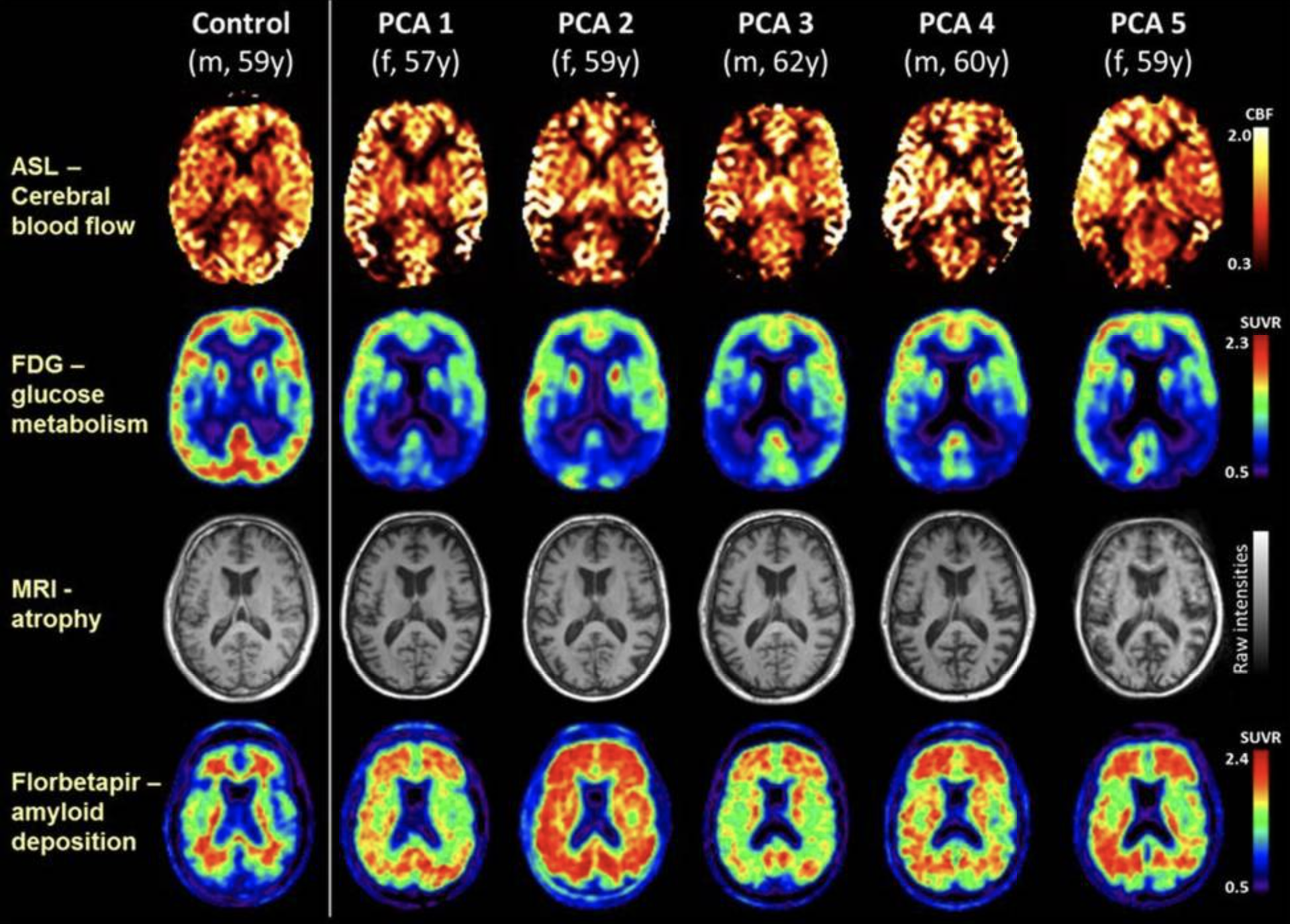

Lehmann M,Melbourne A,Dickson JC,Ahmed RM,Modat M,Cardoso MJ,Thomas DL,De Vita E,Crutch SJ,Warren JD,Mahoney CJ,Bomanji J,Hutton BF,Fox NC,Golay X,Ourselin S,Schott JM, A novel use of arterial spin labelling MRI to demonstrate focal hypoperfusion in individuals with posterior cortical atrophy: a multimodal imaging study. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2016 Sep;

[PubMed PMID: 26733599]

[21]

Paterson RW,Toombs J,Slattery CF,Nicholas JM,Andreasson U,Magdalinou NK,Blennow K,Warren JD,Mummery CJ,Rossor MN,Lunn MP,Crutch SJ,Fox NC,Zetterberg H,Schott JM, Dissecting IWG-2 typical and atypical Alzheimer's disease: insights from cerebrospinal fluid analysis. Journal of neurology. 2015 Dec;

[PubMed PMID: 26410752]

[22]

Maia da Silva MN,Millington RS,Bridge H,James-Galton M,Plant GT, Visual Dysfunction in Posterior Cortical Atrophy. Frontiers in neurology. 2017

[PubMed PMID: 28861031]

[23]

Kim E,Lee Y,Lee J,Han SH, A case with cholinesterase inhibitor responsive asymmetric posterior cortical atrophy. Clinical neurology and neurosurgery. 2005 Dec;

[PubMed PMID: 16311158]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[24]

Suárez-González A,Henley SM,Walton J,Crutch SJ, Posterior cortical atrophy: an atypical variant of Alzheimer disease. The Psychiatric clinics of North America. 2015 Jun;

[PubMed PMID: 25998111]

[25]

Weill-Chounlamountry A,Alves J,Pradat-Diehl P, Non-pharmacological intervention for posterior cortical atrophy. World journal of clinical cases. 2016 Aug 16;

[PubMed PMID: 27574605]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[26]

Townley RA,Dawson ET,Drubach DA, Heterozygous genotype at codon 129 correlates with prolonged disease course in Heidenhain variant sporadic CJD: case report. Neurocase. 2018 Feb;

[PubMed PMID: 29436943]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence