Continuing Education Activity

Single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and positron emission tomography (PET) are imaging modalities in nuclear medicine that can be used to evaluate cerebral hemodynamics. SPECT and PET cerebral perfusion examinations have an important role in evaluating multiple diagnoses, including but not limited to stroke, chronic cerebrovascular disease, epilepsy, and dementia. This activity reviews and explains the role of the interprofessional team in managing patients who undergo SPECT and PET cerebral perfusion exams.

Objectives:

- Describe the common indications for PET and SPECT cerebral perfusion imaging.

- Review common abnormalities seen on PET and SPECT cerebral perfusion imaging.

- Identify common radiotracers and augmenting medications used in PET and SPECT cerebral perfusion imaging and their associated contraindications and complications.

- Summarize the basic principles of how PET and SPECT cerebral perfusion imaging is performed and the inherent benefits and drawbacks of each imaging modality.

Introduction

Cerebral perfusion imaging can be performed with a variety of different imaging modalities, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), ultrasound, and nuclear imaging.

This article will focus on cerebral perfusion imaging in nuclear medicine, specifically single-photon emission CT (SPECT) and positron emission tomography (PET). Both PET and SPECT have important roles in evaluating stroke, chronic cerebrovascular disease, and epilepsy, among other diagnoses, by providing qualitative and quantitative information about cerebral hemodynamics.

Anatomy and Physiology

Multiple different radiopharmaceuticals have been developed to evaluate cerebral hemodynamics. SPECT radiotracers such as technetium-99m ethyl cysteinate dimer (Tc99m-ECD), technetium-99m hexamethylpropylene amine oxime (Tc99m-HMPAO), and N-isopropyl-p-I-123 Iodoamphetamine (I-123 IMP) can be used to obtain comparative measurements of regional cerebral blood flow (CBF).[1]

These radiotracers are lipophilic, allowing them to cross the blood-brain barrier easily. Once the blood-brain barrier is crossed, these compounds become hydrophilic, which will enable them to be retained within the brain for prolonged periods. Compared to Tc99m-HMPAO, Tc99m-ECD has a higher uptake in the gray matter, giving images better gray-to-white matter differentiation.[2]

These radiopharmaceuticals are useful in the setting of epilepsy because they allow time for a patient to be stabilized during the acute ictal state before transferring the patient to the SPECT scanner for imaging.[3]

Absolute measurements of CBF can be obtained using xenon-133 (Xe-133), unlike most radiotracers used in SPECT cerebral perfusion imaging. The most common method for obtaining absolute measurements of CBF in SPECT cerebral perfusion imaging is through correlating levels of Xe-133 in arterial blood gas samples and deriving an arterial input function, an equation that describes the kinetics of radiotracer uptake into the brain.[2]

With the ability of PET scanners to look at metabolic information such as oxygen and glucose metabolism in addition to cerebral hemodynamics, absolute quantitative information about cerebral hemodynamics is more often obtained using PET rather than SPECT. The benefit of absolute quantitative CBF flow measurements in clinical practice is somewhat limited as comparative quantitative measurements, and qualitative analysis tend to give the majority of clinically relevant information.

PET radiotracers such as intravenous H215O (oxygen 15-labeled water) can be used to measure absolute CBF. Inhaled 15O2 can measure regional oxygen extraction fraction (rOEF) and regional cerebral oxygen metabolism (cMRO2). C15O can be used to obtain cerebral blood volume measurements (CBV).[4] In addition, radiopharmaceuticals such as F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose (F-18 FDG) can be used to assess metabolic activity in areas of the brain by identifying areas of abnormal glucose uptake.[2]

Absolute quantitative measurements of CBF can be obtained in PET using intravenous oxygen-15 labeled water by measuring arterial blood levels of radiotracer and using arterial input functions, similar to how absolute CBF is measured in SPECT with Xe-133.[5] Less invasive methods of measuring absolute CBF that do not require arterial access have been developed to predict radiotracer uptake kinetics from imaging findings alone.[6]

Low-molecular-weight isotopes, which are commonly used in PET radiopharmaceuticals, such as F-18 and O-15, require a cyclotron to produce and tend to have short half-lives. O-15-labeled compounds have half-lives that typically range from 2 to 20 minutes, while F-18-labeled compounds tend to have half-lives of up to 110 minutes.[7]

Because of this, a significant amount of coordination is required between radiopharmaceutical providers and health care institutions to coordinate the delivery of radiopharmaceuticals and perform PET examinations.

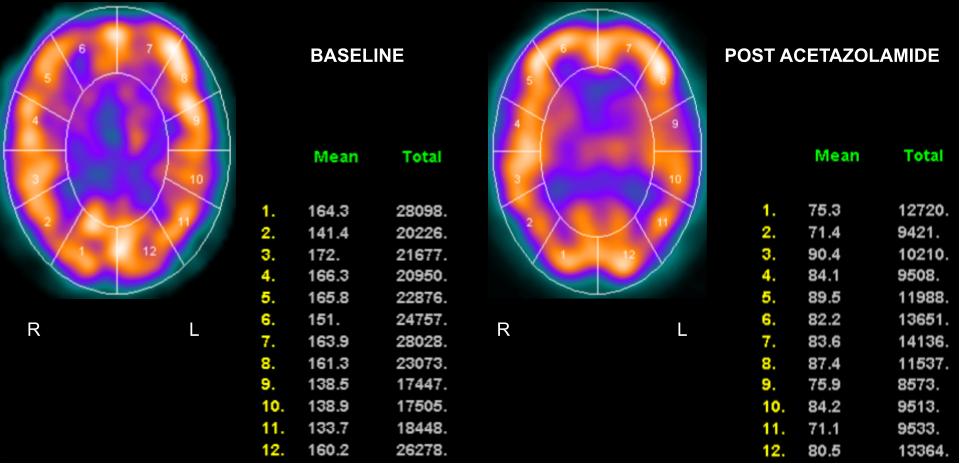

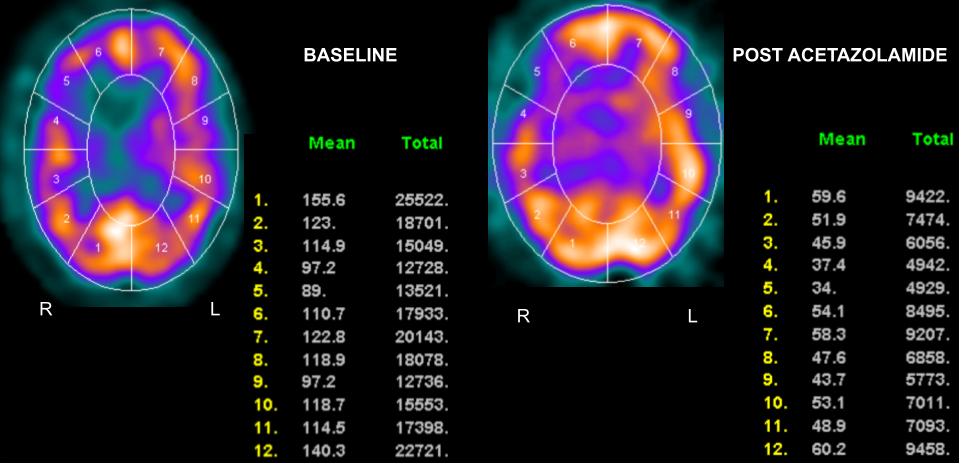

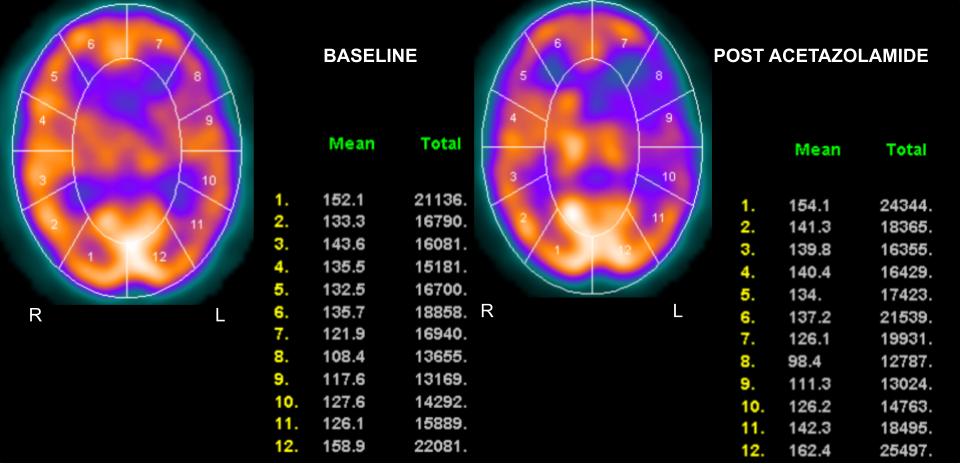

Acetazolamide can be used in both SPECT and PET cerebral perfusion imaging to assess cerebral vascular reserve in patients with chronic cerebrovascular occlusive disease. In healthy brain tissue, acetazolamide inhibits carbonic anhydrase resulting in increased CO2 production and reflexive vasodilation by cerebral vasculature. This results in increased CBF due to decreased vascular resistance. Normal areas of the brain will have an approximately 20 to 30% increase in CBF after administration of acetazolamide.

In areas of the brain with abnormally decreased cerebral perfusion pressure, there is reflexive vasodilation of the cerebral vasculature in an attempt to restore normal cerebral blood flow. Because the vasculature is already dilated in areas of the brain with decreased cerebral perfusion pressure, it cannot respond to acetazolamide to the same degree as normal brain tissue.[8] CBF in the under-perfused tissue can thus not increase to the same degree as normal brain tissue in response to acetazolamide.[8]

Indications

A nuclear medicine cerebral perfusion scan can be used for these indications:

- Identification of epileptogenic foci for pre-surgical planning[9][10]

- Evaluation of stroke risk in patients with chronic cerebrovascular disease[8][11]

- Evaluation of stroke risk in patients who may be candidates for carotid artery sacrifice procedures[12][13]

- Identification of ischemic penumbra and core infarcts in acute stroke[14]

- Differentiating different subtypes of dementia[15]

- Confirmation of brain death[16]

- Identifying cerebral lesions in the setting of trauma that are occult on MRI or CT[17]

Contraindications

No strict contraindications exist for SPECT or PET imaging besides the inability to cooperate with the exam or position the patient in the scanner safely. Anaphylactic reactions to SPECT/PET radiotracers are extremely rare and may warrant using a different type of radiotracer.[18]

Acetazolamide is contraindicated in patients with sulfa allergies, severe electrolyte imbalances, and severe liver or kidney dysfunction.

Equipment

Both SPECT and PET scanners collect three-dimensional data by detecting photons released by various radiopharmaceuticals. SPECT radiopharmaceuticals directly emit photons which are detected by SPECT cameras. In the case of PET, radiotracers emit positrons which, upon annihilation with adjacent electrons, subsequently release two photons in opposite directions. The PET scanner then detects the presence of both photons simultaneously to differentiate a "true" radiotracer signal from scatter radiation. Because PET uses this process of "coincidence detection," a physical collimator to block scatter radiation is not needed, unlike in SPECT.[19]

This is one of the reasons why PET images tend to have higher resolution when compared to SPECT images, as they tend to have inherently less noise from scatter radiation. In addition, the number of counts acquired while scanning is generally higher in PET when compared to SPECT, giving greater image resolution.

One of the advantages of SPECT scanners is their ability to detect multiple different radiotracers at once based on the differing energies of their photons. This isn't possible in PET because all positrons emit photons with the same energy of approximately 0.511 MeV.[20]

In comparison, because SPECT radiotracers tend to have photons with a lesser MeV when compared to PET radiotracers, they tend to produce a weaker signal, resulting in an image with inherently less resolution.

PET and SPECT cameras coupled with CT or MRI scanners can provide greater anatomic detail. Most PET scanners in use today are hybrid PET/CT scanners, while hybrid SPECT/CT scanners are less common. SPECT scanners dedicated to cerebral imaging are commercially available, but more basic SPECT scanners, which can be used to image any organ system, are much more common.

In addition to giving greater anatomic detail, PET/CT and SPECT/CT scanners benefit from being able to standardize measurements of radiotracer activity based on the density of the surrounding tissue in a process called CT attenuation correction. This process can also be done using a prior CT, although the results are not as accurate due to inherent differences in patient positioning.

Preparation

Patients should be advised to avoid caffeine, alcohol, and nicotine at least 10 hours before the exam as they can cause alterations in cerebral hemodynamics, which may cause confounding results. Injections should be performed in a dimly lit room, and the patient should be given time to relax before the radiopharmaceutical injection.

Intravenous access should be established at least 10 minutes before radiotracer injection. In addition, the patient should be instructed not to talk or interact with the technologist within 5-10 minutes of radiotracer injection.[19]

Technique or Treatment

The Society of Nuclear Medicine & Molecular Imaging (SNMMI) and the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM) has endorsed protocols for various nuclear medicine studies. In SPECT brain death examinations with Tc99m-HMPAO or Tc99m-ECD, the SNMMI endorses taking dynamic images during radiotracer injection followed by anterior and lateral planar images of the brain after 20 minutes.

If a non-brain-binding radiopharmaceutical is utilized, such as Tc99m-diethylenetriamine pentaacetate (Tc99m-DTPA), the SNMMI endorses taking anterior, right lateral, left lateral, and posterior planar images until radiotracer counts are 500,000 to 1,000,000 per image.

Dynamic images are also obtained during radiotracer injection if non-brain-binding radiopharmaceuticals are utilized. Three dimensional SPECT images may also be obtained in the case of Tc99m-HMPAO and Tc99m-ECD to help differentiate radiotracer activity within the brain from radiotracer activity in the scalp.[21]

In addition, both the SNMMI and EANM have endorsed a set of general guidelines for using Tc99m radiopharmaceuticals in cerebral perfusion imaging related to patient preparation and post-image processing.[22]

Outside of brain death examinations, no specific protocols for cerebral perfusion imaging have been endorsed by the SNMMI or EANM. Protocols for SPECT and PET cerebral perfusion, which are not performed for brain death, vary but generally include taking dynamic images during radiotracer injection followed by SPECT images at the expected time of peak radiotracer activity.

Complications

Research on the adverse effects of common cerebral perfusion radiopharmaceuticals is extremely limited. Generally speaking, adverse reactions to radiopharmaceuticals include flushing, nausea, and pain at the injection site. There are very few reports of anaphylaxis secondary to radiopharmaceutical administration.[23]

Adverse reactions to augmenting pharmaceuticals such as acetazolamide are much more common. The most common side effects associated with intravenous acetazolamide include flushing, paresthesias, perioral numbness, headache, and rarely anaphylaxis.

Clinical Significance

Brain Death

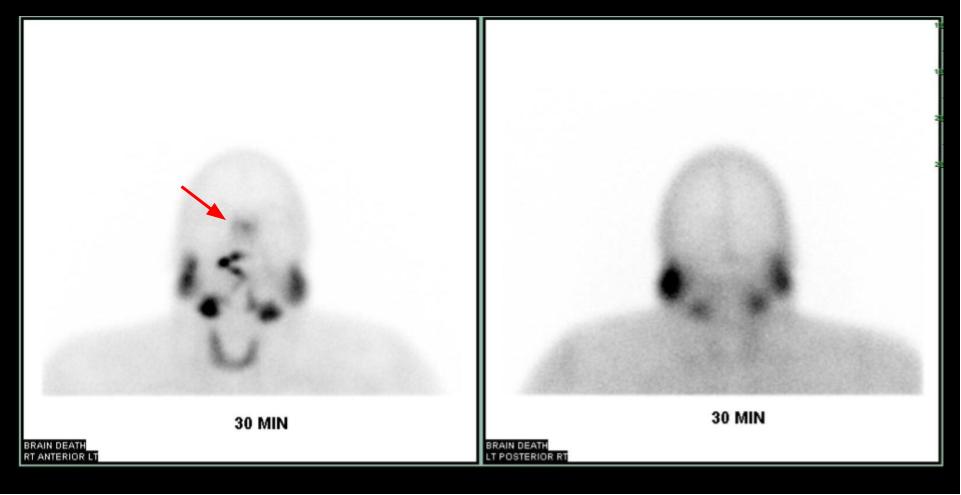

Confirmation of brain death in nuclear cerebral perfusion imaging is most commonly performed with SPECT by using a brain-binding perfusion agent such as Tc99m-HMPAO or Tc99m-ECD. Most protocols involve obtaining dynamic planar images during radiopharmaceutical injection in the angiographic phase, followed by static planar images of the brain. Three-dimensional SPECT images are commonly obtained in addition to dynamic and planar images to determine if areas of apparently increased radiotracer activity on planar images are truly within the brain or in the adjacent scalp.

On dynamic images, patients who have undergone brain death will demonstrate blood flow in the internal carotids, which terminates at the skull base due to increased cerebral edema and tamponade of the intracerebral arterial system. On static planar images, patients with brain death will exhibit decreased radiotracer activity throughout the brain as there is significantly decreased or absent perfusion. Redistribution of blood flow into the external carotid arteries causes increased radiotracer distribution to the arteries of the face and nose, resulting in the characteristic "hot nose" sign (Figure 1).[16]

PET could, in theory, be used for brain death examinations but has not gained widespread use due to the short half-lives of radiotracers and the degree of coordination required to perform PET examinations.

Acute Stroke

SPECT brain-binding perfusion agents such as Tc99m-HMPAO and Tc99m-ECD are commonly used in the setting of acute stroke. Tc99m-ECD has the added benefit of having higher gray-to-white matter differentiation. In PET cerebral perfusion, intravenous oxygen-15 labeled water is commonly used as a perfusion radiotracer, while inhaled C15O can be used for estimates of CBV.[24]

Inhaled 15O can be used to measure rOEF and cMRO2. Because of the tight connection between cerebral perfusion and glucose metabolism, F-18 FDG PET examinations can also be used to identify ischemic brain tissue.

SPECT cerebral perfusion scans can help identify patients who will benefit from intravenous thrombolysis and patients who have a high risk of hemorrhagic conversion in response to intravenous thrombolysis. Generally speaking, areas of the brain with a CBF greater than 55% of the cerebellum tend to benefit from intravenous thrombolysis even if given outside of a 6-hour window. If under perfused brain tissue has a CBF that is 35 to 55% of that of the cerebellum, thrombolysis is generally effective within 6 hours of symptom onset. If under perfused brain tissue has a CBF that is less than 35% of that of the cerebellum, there is a significantly higher risk of intracerebral hemorrhage with intravenous thrombolysis regardless of the time of symptom onset.[25]

PET cerebral perfusion imaging for acute stroke is limited to a few specialized medical centers. Regardless, research on cerebral hemodynamics using PET imaging was crucial for understanding the pathophysiology of stroke and creating definitions for ischemic penumbrae and core infarcts in various other modalities such as SPECT, MRI, and CT.[24]

In Lee et al., a "four-compartment model" is proposed, one of the most widely accepted models describing the abnormal cerebral hemodynamics seen in stroke. In Lee et al., an ischemic penumbra is defined as an area with mild decreases in cMRO2, corresponding with an average CBF of approximately 35% of baseline and an elevated mean transit time of greater than 6-8 seconds. CBV may be elevated, normal, or decreased in ischemic penumbrae.

In comparison, an ischemic core infarct is defined as an area with moderate decreases in cMRO2, which correspond with an average CBF of less than 20% of baseline. CBV is decreased in an ischemic core infarct, and the mean transit time should be greater than 6-8 seconds. In both ischemic penumbra and core infarcts, rOEF is increased.

Using the principles described by Lee et al., it is possible to use relative measurements of cerebral blood flow, mean transit time, and cerebral blood volume to try and predict areas of ischemic penumbra and core infarct without obtaining measurements of cMRO2. This is done by comparing the cerebral hemodynamics in a region of interest with the cerebral hemodynamics of the corresponding opposite side of the brain.

Chronic Cerebrovascular Disorders

In patients with chronic cerebral artery or carotid artery occlusion, SPECT and PET can be used to assess the risk of subsequent stroke and the potential benefits of revascularization. In both SPECT and PET cerebral perfusion imaging, the examination can be augmented with intravenous acetazolamide, which causes vasodilation of the cerebral vasculature. Areas of the brain with normal cerebral perfusion pressure tend to have increases in CBF of approximately 30%.

In areas of the brain with decreased cerebral perfusion pressure, there is reflexive vasodilation through auto-regulation in an attempt to restore normal CBF. If the vasculature is already reflexively dilated due to reduced cerebral perfusion pressure, such as can be seen in ischemic tissue, it responds to a lesser degree to acetazolamide, and CBF will not increase as significantly in that region.[8]

Areas that have a CBF that increases minimally or does not increase with the administration of acetazolamide are said to have decreased cerebral vascular reserve (Figures 2,3, and 4). Patients who benefit the most from revascularization procedures tend to have a pattern of cerebral hemodynamic parameters known as the intracerebral steal phenomenon. In intracerebral steal phenomenon, acetazolamide administration causes vasodilation in normal brain tissue but is unable to cause vasodilation in areas of decreased perfusion as it already has maximally dilated vasculature. Because of this, blood is shunted away from the area of ischemia and is directed toward healthy brain tissue, which causes further decreases in CBF to the ischemic area.[11]

Balloon Occlusion Testing and Assessment of Stroke Risk after Carotid Artery Sacrifice

Carotid artery sacrifice is a procedure often performed to treat massive carotid artery aneurysms or neoplasms, which are inseparable from the carotid artery requiring excision.[13] SPECT or PET cerebral perfusion imaging can be performed to help predict the risk of stroke and overall mortality after carotid artery sacrifice procedures.[12][13]

SPECT perfusion radiotracers such as Tc99m-HMPAO or PET perfusion radiotracers such as oxygen-15 labeled water can be administered intravenously after occluding the carotid artery with a balloon catheter for approximately 5 minutes. If a decrease in CBF greater than 10% of the contralateral cerebral hemisphere is identified, there is a significantly higher risk of stroke and a higher risk of overall mortality in patients who undergo carotid artery sacrifice.

Epilepsy

SPECT cerebral perfusion has become one of the most useful imaging modalities to localize epileptogenic foci. Because SPECT radiopharmaceuticals such as Tc99m-HMPAO and Tc99m-ECD have prolonged retention rates in the brain, healthcare providers have more time to stabilize an ictal patient before transferring them to the SPECT scanner for imaging. PET has a lesser role in the evaluation of epilepsy due to the short half-lives of radiotracers used and is usually limited to examinations with F-18 FDG in the interictal period.

Epileptogenic foci tend to have increased perfusion and glucose metabolism in the ictal period while the patient is seizing and tend to have decreased perfusion and glucose metabolism in the interictal period when the patient is between seizure episodes. However, information obtained in the interictal period for PET and SPECT cerebral perfusion imaging tends to be less reliable in localizing epileptogenic foci than in the ictal period. Because of this, SPECT imaging during the ictal period has become the exam of choice in cerebral perfusion imaging to help identify epileptogenic foci.[9][10]

Crossed Cerebellar Diaschisis

Crossed cerebellar diaschisis is a finding seen on PET and SPECT cerebral perfusion imaging where a supratentorial lesion, usually an infarct, results in decreased perfusion and metabolism in the contralateral cerebellar hemisphere. This can be assessed with brain-binding perfusion agents such as Tc99m-HMPAO or Tc99m-ECD in SPECT.[26]

In PET, this can be seen either with perfusion agents such as oxygen-15 labeled water or with metabolic agents such as F-18 FDG.[27] Crossed cerebellar diaschisis can also be seen in the setting of traumatic brain injury, tumors, and encephalitis and occurs through disruption of the corticopontocerebellar pathway. This imaging finding is benign in itself but may be important in indicating a contralateral supratentorial lesion. The size of the supratentorial lesion does not directly influence the presence or magnitude of abnormality in crossed cerebellar diaschisis but rather the location of the lesion in the brain.[26]

Dementia

Patterns of cerebral perfusion abnormalities can help differentiate specific subtypes of dementia. Because cerebral perfusion and metabolism are closely linked due to the brain's inability to store glucose, evaluation can be performed with SPECT perfusion agents such as Tc99m-HMPAO or PET agents such as F-18 FDG.[28]

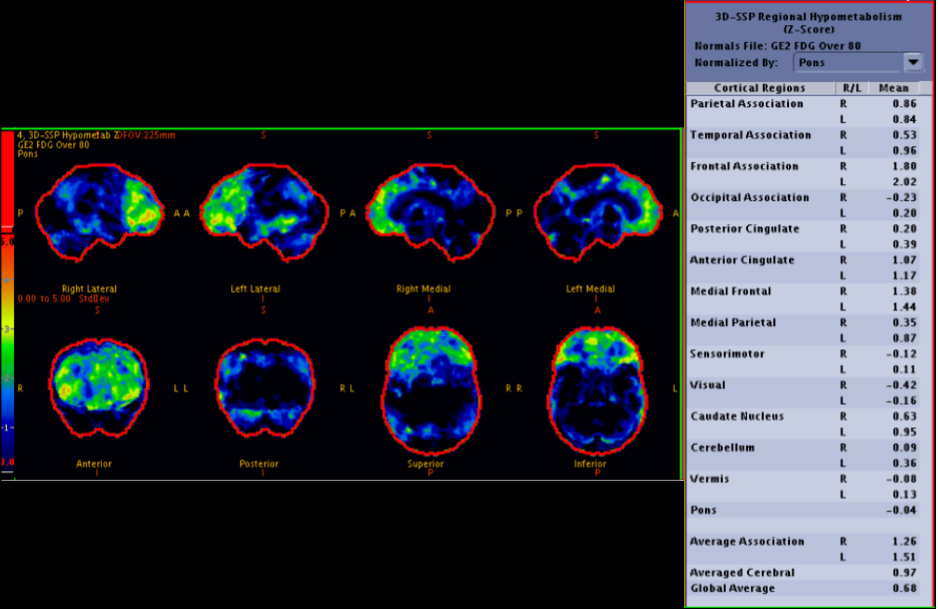

Frontotemporal dementia, including Pick disease, tends to have decreased perfusion in the frontal lobes and anterior temporal lobes (Figure 5). In Alzheimer dementia, there tends to be decreased perfusion in the temporal and parietal lobes with characteristic sparing of the sensorimotor cortex, visual cortex, and basal ganglia (Figure 6). Patients with Lewy body dementia can also have decreased perfusion in the temporal and parietal lobes but differ in that there is often involvement of the sensorimotor strip or occipital lobes (Figure 7).[15] Patients with Huntington disease can demonstrate decreased perfusion in the caudate and lentiform nuclei.[29]

Trauma

SPECT perfusion imaging can be used to identify lesions in patients with a previous traumatic brain injury that are occult on CT or MRI and is especially useful in the presence of neurobehavioral symptoms. Similar to dementia, areas of decreased perfusion correlate with certain neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with traumatic brain injury and can help guide treatment decisions.[17]

When PET imaging is performed in the setting of traumatic brain injury, it is usually performed with F-18 FDG to look at areas of decreased metabolism. As stated before, cerebral perfusion and glucose metabolism are closely linked due to the brain's relative inability to store glucose.[30]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

In both PET and SPECT cerebral perfusion examinations, providers should confirm that the patient has abstained from alcohol, caffeine, or nicotine use at least 10 hours before the exam.[22][31][Level 2]

In the case of vitally unstable patients, continuous monitoring of patient vitals and pulse oximetry by nursing staff may provide benefits. If SPECT or PET cerebral imaging is required in a patient who cannot cooperate with the exam, an anesthesia consult may benefit the case, considering that sedating medications may decrease the specificity of imaging findings.

In situations where sedation is required, it is recommended that sedation be administered at least 5 minutes after radiotracer administration. Resuscitative equipment should always be present within the imaging suite to ensure prompt treatment of emergent conditions as necessary.