Continuing Education Activity

Ultrasound is an imaging modality that has been in clinical use for approximately 50 years, though its utility and efficacy have dramatically improved since it was first introduced. Ultrasound is portable, cost-effective and does not require radiation or contrast. This activity reviews the use of ultrasound in the detection of many abdominal pathologies, with a particular focus on indications, contraindications, and technique involved in performing a transabdominal ultrasound. This activity highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the care of patients undergoing this procedure.

Objectives:

- Identify the indications for an abdominal ultrasound.

- Describe the technique involved in performing an abdominal ultrasound.

- Outline the limitations of an abdominal ultrasound.

- Explain interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to enhance the utilization of abdominal ultrasound and improve patient outcomes.

Introduction

Ultrasound is an imaging modality that has been in clinical use for approximately 50 years. Sokolov first described the potential for using this technology to produce low-resolution images in 1939. Later understanding of the piezoelectric effect and further technological refinements have resulted in machine advancements. We have seen the machine sizes dramatically decrease; some of the earliest machines were the size of refrigerators while recently we have seen the introduction of transducers that are compatible with smartphones. Although ultrasound technology can be utilized in a variety of different settings and body locations, the focus of this article will be on transabdominal ultrasound, its definition, indications and diagnostic pearls and pitfalls.[1][2]

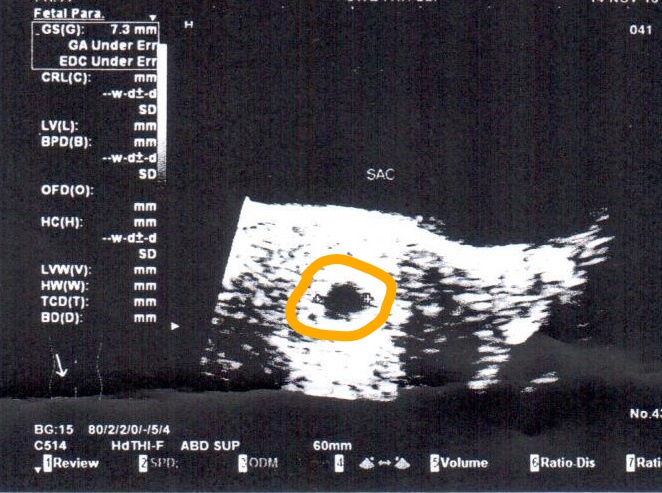

Transabdominal ultrasound was initially utilized in its most colloquial setting of pregnancy in the 1960s.[3][4] It is now utilized for visualization of multiple abdominal organs, both intraperitoneal and retroperitoneal. By definition, any evaluation with an ultrasound transducer overlying the abdominal wall can be considered a transabdominal ultrasound. Transabdominal ultrasound can be applied to visualize the liver, gallbladder[5], kidneys, pancreas, small and large intestine, appendix, bladder, uterus, adnexa, spleen, stomach, aorta, and IVC. In the setting of obstetrics and gynecology (OBGYN), the transabdominal approach is usually performed to evaluate for possible pelvic pathology or pregnancy in a less invasive manner. In the emergency department (ED) a transabdominal ultrasound is most commonly utilized to evaluate for intrauterine pregnancy[6], cholelithiasis, intraabdominal free fluid, abdominal aortic aneurysm, and hydronephrosis.

Emergency physicians (EPs) perform a limited point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) in comparison to formal radiology transabdominal ultrasounds. The EP performs the former compared to the latter, and a trained sonographer performs a thorough and complete examination of the organ. ED POCUS is focused on binary questions that are rapidly evaluated at the bedside and direct patient care immediately. For example: “Is there an intrauterine pregnancy?” In most cases when an intrauterine pregnancy is identified, the examination is complete. While both EPs and sonographers perform a transabdominal ultrasound, the performance characteristics and goals vary.[7]

Anatomy and Physiology

Sonographic anatomy, similar to gross anatomy, recognizes landmarks and scanning conventions that were originally defined by specialties like obstetrics and radiology. For example, the gallbladder is located under the liver and has great variability with its location. The sonographic cystic pedicle (SCP) is a landmark utilized to ensure correct identification of the gallbladder.[8] Originally this was called the main lobar fissure (MLF), which was thought to correlate to the main portal fissure. Cadaveric dissection later found this to be an extrahepatic structure paralleling the rim of the main lobar fissure and was re-named the SCP, which includes the cystic duct, ensheathing fat and blood vessels. Each organ of interest has its varying anatomy and ultrasound scanning convention to acquire the desired image or measurements needed to identify pathology.

Indications

Abdominal Pain

Right Upper Quadrant[9]: Evaluation for free fluid, cholelithiasis, choledocholithiasis, hepatic abscess mass, hydronephrosis

Right Lower Quadrant: Evaluation for appendicitis[10], intussusception, psoas abscess

Left Upper Quadrant: Evaluation for free fluid, splenic pathology (laceration or fracture), stomach, hydronephrosis

Left Lower Quadrant: Evaluation for diverticulitis, small bowel obstruction[11]

Epigastric: Evaluation for pancreatic mass, abdominal aortic aneurysm

Pelvic: Evaluation for free fluid, urinary retention, pregnancy, ectopic pregnancy, pelvic mass

Blunt or Penetrating Abdominal Trauma

- Evaluation of free fluid[12]

Vaginal Bleeding

- Evaluation for pregnancy, ectopic pregnancy, uterine pathology, abortion (fetal parts)

Hypotension:

- Evaluation for infectious sources listed above, vascular assessment of inferior vena cava as a surrogate marker for volume status or volume loss from hemorrhage[13], abdominal aortic aneurysm

Hematuria

- Evaluation for genitourinary mass, nephrolithiasis, hydronephrosis

Contraindications

There are no absolute contraindications to performing a transabdominal ultrasound. One should take care not to scan over a wound or incision to avoid contamination and infection. Color and pulsed Doppler should not be applied to a fetus because of the theoretical radiation risk to the fetus.[14]

Equipment

Transabdominal ultrasound should be performed with a low-frequency probe, ideally with a large convex footprint. Most common probes utilized are the curvilinear or phased array probes. Disinfectant wipes and cleaning equipment are institution specific and usually determined by the infectious disease department.

Personnel

A trained provider can perform a transabdominal ultrasound. Registered diagnostic medical sonographer (RDMS) have different requirements and certification than most primary providers performing a point-of-care ultrasound at the bedside. For example, emergency physicians are required to perform and interpret a minimum of 25 to 50 cardiac ultrasound exams upon residency graduation.

Preparation

Ensure that the probe and machine are cleaned before entering a patient room. The correct probes should be connected to the machine. The patient is ideally lying in a supine position on a stretcher with his or her abdomen exposed. Care should be taken to avoid unnecessary exposure with the use of towels tucked around the gown and undergarment edges. This will also aid in keeping unexposed areas clean from ultrasound gel.

For dominant right-hand operators, the ultrasound machine should be positioned at the patient’s anatomic right near the head of the bed, plugged in (if applicable) and turned on. The lights should be dimmed if possible. For evaluation of the gallbladder, being in a fasting state aids in the engorgement of the gallbladder and better visualization. When evaluating the uterus, informing the patient to maintain a full bladder will aid in visualization secondary to fluid in the bladder providing an acoustic window to deeper structures.

Technique or Treatment

A low-frequency convex probe is best for a transabdominal ultrasound. Alternatively, a phased array probe can be used if a convex probe is not available. The settings on the ultrasound machine should be set to the desired exam being performed, for example, abdominal, FAST, vascular. The settings on the machine optimize image quality for the scan being performed. Generally, the probe indicator is always aimed cephalad (toward the patient’s head) or to the patient’s right side. Specific scanning technique is utilized depending on the organ or pathology being evaluated. For example, when evaluating the gallbladder, the probe is placed in a sagittal plane (with the indicator cephalad) in the right upper quadrant just inferior to the costal margin. The operator then slides the probe medial and lateral along the costal margin while maintaining the sagittal plane (cephalad) evaluating for the optimal sonographic window for image acquisition. Asking the patient to take a deep breath and hold it causes the diaphragm to contract, displacing the liver and gallbladder inferior, and aiding in image acquisition. A coronal scan of the right upper quadrant is another technique that can allow for gallbladder evaluation. With the probe placed on the patient’s right in the mid-axillary line, indicator cephalad, the operator can then fan the probe anterior and posterior through the liver in an attempt to acquire an optimal window to evaluate the gallbladder. The gallbladder is then evaluated for (1) stones or sludge, (2) wall thickening (normal less than 3 mm), (3) presence of a sonographic Murphy's sign, and (4) pericholecystic fluid.[15] The presence of all four is very sensitive and specific for cholecystitis. This is an example of one specific area of transabdominal ultrasound. There are specific techniques for most abdominal organs and underlying pathologies that can be evaluated using ultrasound.

Complications

Transabdominal ultrasound, like most diagnostic ultrasound applications, is associated with little if any risk. There may be some associated discomfort when pressure is applied.

Clinical Significance

Transabdominal ultrasound is an inexpensive, safe, rapid way of assessing for multiple pathologies. It can be used to effectively rule in or out specific pathologies such as cholecystitis without the need for further imaging in many cases. This can lead to expedited diagnosis, treatment, and a reduction in ionizing radiation.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

It is the healthcare providers responsibility to decrease the harm caused by ionizing radiation. ALARA principle supported by the US-Nuclear Regulatory Commission and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).[16][17]