Continuing Education Activity

The World Health Organization defines dehydration as a condition that results from excessive loss of body water. The most common causes of dehydration in children are vomiting and diarrhea. This activity describes the causes and pathophysiology of pediatric dehydration and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in its management.

Objectives:

Identify the etiology of pediatric dehydration.

Recall the presentation of pediatric dehydration.

List the treatment and management options available for pediatric dehydration.

Explain interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance the management of pediatric dehydration and improve outcomes.

Introduction

The World Health Organization defines dehydration as a condition that results from excessive loss of body water. The most common causes of dehydration in children are vomiting and diarrhea.

Etiology

Infants and young children are particularly susceptible to diarrheal disease and dehydration. Reasons include higher metabolic rates, inability to communicate their needs or hydrate themselves, and increased insensible losses. Other causes of dehydration may be the result of other disease processes resulting in fluid loss, which include diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), diabetes insipidus, burns, excessive sweating, and third spacing. Dehydration may also be the result of decreased intake along with ongoing losses. In addition to total body water losses, electrolyte abnormalities may exist. Infants and children have higher metabolic needs, and that makes them more susceptible to dehydration.[1]

Epidemiology

Dehydration is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in infants and young children worldwide. Each year approximately 760,000 children of diarrheal disease worldwide. Most cases of dehydration in children are the consequence of acute gastroenteritis.

Acute gastroenteritis in the United States is usually infectious in etiology. Viral infections, including rotavirus, norovirus, and enteroviruses, cause 75 to 90 percent of infectious diarrhea cases. Bacterial pathogens cause less than 20 percent of cases. Common bacterial causes include Salmonella, Shigella, and Escherichia coli. Approximately 10 percent of bacterial disease occurs secondary to diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Parasites such as Giardia and Cryptosporidium account for less than 5 percent of cases.

Pathophysiology

Dehydration causes a decrease in total body water in both the intracellular and extracellular fluid volumes. Volume depletion closely correlates with the signs and symptoms of dehydration. The total body water (TBW) in humans is distributed in two major compartments. two-thirds of the TBW is in the intracellular compartment, and the other one-third is distributed between interstitial space (75%) and plasma (25%). The total body water is higher in infants and children as compared to adults. In infants, it is 70% of the total weight, whereas it is 65% and 60%, respectively, in children and adults. As indicated earlier, dehydration is total water depletion with respect to sodium, and volume depletion is the decrease in the circulation volume. Volume depletion is seen in acute blood loss and burns, whereas distributive volume depletion is seen in sepsis and anaphylaxis. In much of the literature, the distinction between dehydration and volume depletion is a blur.[1]

Metabolic acidosis is seen in infants and children with dehydration, the pathophysiology of which is multifactorial.

1. excess bicarbonate loss in the diarrhea stool or in the Urine is certain types of renal tubular acidosis

2. Ketosis secondary to the glycogen depletion seen in starvation which sets in infants and children much earlier when compared to adults.

3. Lactic acid production secondary to poor tissue perfusion

4. Hydrogen ion retention by the kidney from decreased renal perfusion and decreased glomerular filtration rate.

Children with pyloric stenosis have very unique electrolyte abnormalities from the excessive emesis of gastric contents. This is seen mostly in older children. They lose chloride, sodium, and potassium in addition to volume resulting in hypochloremic, hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis. The kidney excretes base in the form of HCO3 ion to maintain acid-base balance of loss of hydrogen ion in the emesis in the form of hydrogen chloride. It is interesting to note that the kidney also excretes hydrogen ions to save sodium and water, which could be the reason for aciduria. A recently published article has shown that many children with pyloric stenosis may not have metabolic alkalosis.

History and Physical

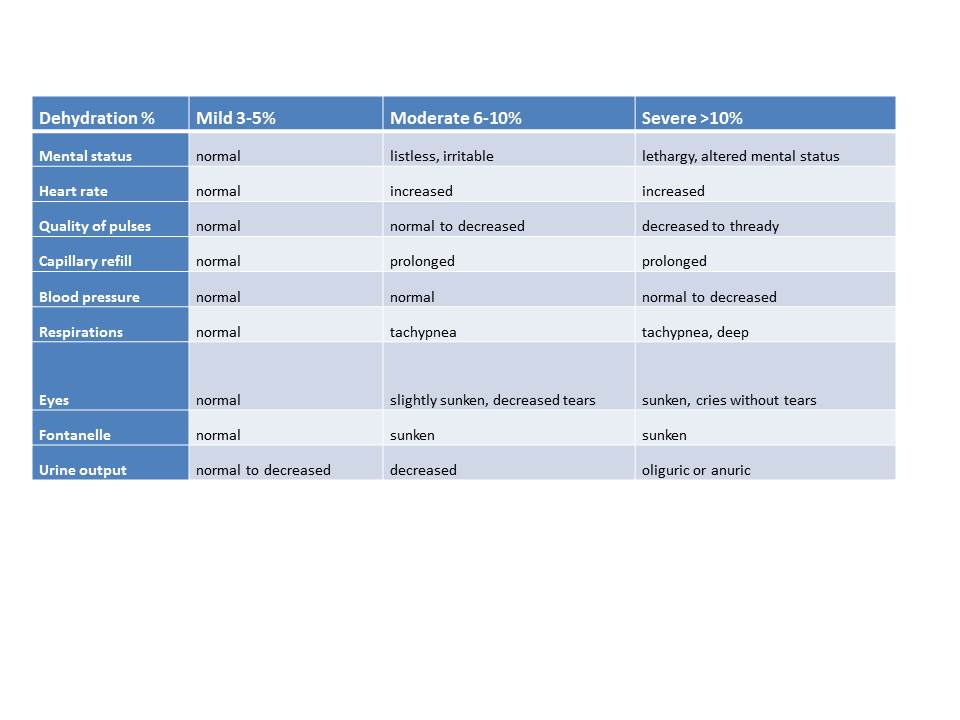

Various signs and symptoms can be present depending on the patient's degree of dehydration. Dehydration is categorized as mild (3% to 5%), moderate (6% to 10%), and severe ( more than 10%). The table below can assist with categorizing the patient's degree of dehydration. The degree of dehydration between an older child and an infant is slightly different as the infant could have total body water (TBW) content of 70% to 80% of the body weight, and older children have TBW of 60% of the body weight. An infant has to lose more body weight than an older child to get to the same level of dehydration.[2] Dehydrated children have dry oral mucosa.

Dehydration% Mild 3% to 5% Moderate 6% to 10% Severe >10%

Mental status Normal Listless, irritable Altered mental

Heart rate Normal Increased Increased

Pulses Normal Decreased Thready

Capillary refill Normal Prolonged Prolonged

Blood pressure Normal Normal Decreased

Respirations Normal Tachypnea Tachypnea

Eyes Normal Slightly sunken Fewer tears

Fontanelle Normal Sunken Sunken

Urine output Normal Decreased Oliguric

(see image below)

Evaluation

Dehydration could be associated with hypo or hyper, or isonatremia. Most cases of dehydration are hyponatremic. In selected cases, electrolyte abnormalities may exist. This includes derangements in sodium levels and acidosis characterized by low bicarbonate levels or elevated lactate levels. For patients with vomiting who have not been able to tolerate oral fluids, hypoglycemia may be present. Evaluation of urine specific gravity and the presence of ketones can assist in the evaluation of dehydration.[3]

Children who were given free water when they have ongoing diarrhea disease can present with hyponatremic dehydration, excess of free water concurrent to excess sodium, and bicarbonate loss in diarrhea. This is also seen in the syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (SIADH). In these cases, the children appear to be more dehydrated and could also present with hyponatremic seizure activity.

Similarly, infants who are fed oral rehydration solution prepared from excess salt or who lost excess free water, as in diabetes insipidus, could have hypernatraemic dehydration

End-tidal carbon dioxide measurements have been studied in an attempt to assess degrees of dehydration greater than five percent in children. This non-invasive approach has promise, but as of now has not proven to be an effective tool in determining the degree of dehydration in children. [4]

Treatment / Management

Priorities in the management of dehydration include early recognition of symptoms, identifying the degree of dehydration, stabilization, and rehydration strategies. [2][5][3]

Symptoms include vomiting, diarrhea, fever, decreased oral intake, inability to keep up with ongoing losses, decreased urine output, progressing to lethargy, and hypovolemic shock.

Mild Dehydration

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends oral rehydration for patients with mild dehydration. Breastfed infants should continue to nurse. Fluids with high sugar content may worsen diarrhea and should be avoided. Children can be fed age-appropriate foods frequently but in small amounts.

Moderate Dehydration

The Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report recommends administering 50 mL to 100 mL of oral rehydration solutions per kilogram per body weight for two to four hours to replace the estimated fluid deficit, with additional oral rehydration solution administered to replace ongoing losses.

Severe Dehydration

For patients who are severely dehydrated, rapid restorations of fluids are required.

Patients who are severely dehydrated can present with altered mental status, lethargy, tachycardia, hypotension, signs of poor perfusion, weak thread pulses, and delayed capillary refill.

Intravenous fluids, starting with 20 ml/kg boluses of normal saline, are required. Multiple boluses may be needed for children in hypovolemic shock. Additional priorities include obtaining a point-of-care glucose test, electrolytes, and urinalysis assessing for elevated specific gravity and ketones. [6]

Hypoglycemia should be assessed at the point of care testing via glucometer and venous blood gas with electrolytes or serum chemistries. It should be treated with intravenous glucose. The dose is 0.5 gm/km to 1 gm/km. This translates to 5 ml/kg to 10 ml/kg of D10, 2 ml/kg to 4 ml/kg of D25, or 1 ml/kg to 2 ml/kg of D50. The use of D50 is usually reserved for adolescent or adult-sized patients using a large bore intravenous line.[7]

Replacement of Fluids

An assessment of the degree of dehydration will determine the fluid replacement. Using tables that can predict the degree of dehydration is helpful. If a previous "well weight" is available, that can be subtracted from the patient's "sick weight" to calculate total weight loss. One kilogram of weight loss equates to one liter of fluid lost.

The rate of replacement is based on the severity of the dehydration. Patients with hypovolemic shock need rapid boluses of isotonic fluid, either normal saline or Ringer's lactate, at 20ml/kg body weight. This could be repeated 3 times with reassessment in between the boluses. Ringer lactate is superior to normal saline in hemorrhagic shock requiring rapid resuscitation with isotonic fluids.[8] This difference is not found in children with severe dehydration from acute diarrheal disease. In these children, the replacement with normal saline and Ringer's lactate did show similar clinical improvement.[9]

Rapid infusion can cause cardiac insufficiency, congestive heart failure, and pulmonary edema. The rapid correction in patients with diabetic ketoacidosis can cause cerebral edema in adolescents and children.

The rate of replacement fluids is calculated after taking into account the maintenance, replacement, and deficit requirement of the patient. The sodium requirements of the children in the hospital are higher than that of the adults. The children have high metabolic needs and have higher insensible loss as they have a higher body surface area. They also have higher respiratory and heart rates, requiring the use of an intravenous solution containing high sodium like D5NS. The deficit is determined by the degree of dehydration, as outlined earlier. The second phase of fluid replacement therapy lasts for 8 hours, during which the child requires 1/2 of the remaining deficit in addition to 1/3rd of the maintenance fluid. The remaining half of the deficit and two-thirds of the daily maintenance therapy is given during the third phase of the therapy, which spans the following 16 hours.

The Holliday-Segar calculation is used for the calculation of maintenance fluid in children, which is 100ml/kg/day for the first 10 kg body weight (BW), then 50 ml/kg/day for the next 10 kg BW, and then 20 ml/kg /day for any BW over and above.[10]

For patients where intravenous access can not be achieved or maintained, other methods can be employed. They include continuous nasogastric hydration and subcutaneous hydration.[11]]

Hypodermoclysis refers to hydrating the subcutaneous space with fluid that can be absorbed systemically. Hypodermoclysis is best reserved for the stable child or infant with mild to moderate dehydration who either fails a trial of fluids by mouth or who needs some degree of rehydration to facilitate gaining intravenous access after a slow subcutaneous fluid bolus has been given.

The process begins with:

The placement of topical anesthetic cream, such as EMLA, cover with an occlusive dressing and wait for 15 to 20 minutes.“Pinch an inch” of skin anywhere, but the most practical site for young children is between the scapulae.Insert a 25-gauge butterfly needle or 24-gauge angiocatheterInject 150 units of hyaluronidase SC (if available).Infuse 20 mL/kg isotonic solution over one hour, repeat as needed, or use this technique as a bridge to intravenous access.

Differential Diagnosis

- Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic nonketoic coma

- Pediatric gastroenteritis

- Pediatric pyloric stenosis

Pearls and Other Issues

Once the patient’s condition has stabilized, hydration therapy continues to replace existing and ongoing losses. Fluid therapy should include maintenance fluids plus replacement of the existing fluid deficit.

Deficit calculation can be determined in several ways. If the patient's weight before the illness is known, it can be subtracted from the current weight. Each kilogram lost would be equivalent to one liter of fluid lost. If the prior weight is not known, multiply the weight in kilograms by the dehydration percent.

For a 10 kg patient who is 10% dehydrated, 0.1 represents 10%

- (10 kg) x (.10) = 1 kilogram

Maintenance fluids can be calculated as follows:

For a patient weighing less than 10 kg, they should receive 100 mL/kg/day.

If the patient weighs less than 20 kg, fluids will include 1000 mL/day plus 50 mL/kg/day for each kilogram between 10 kg and 20 kg.

For patients weighing more than 20 kg, give 1500 mL/day, plus 20 mL/kg/day for each kilogram over 20 kg. Divide the total by 24 to determine the hourly rate.

In hyponatremic dehydration, half of the deficit can be replaced over eight hours, with the remaining half the following sixteen hours. Severe hyponatremia (< 130 mEq/L) or hypernatremic dehydration (> 150 mEq/L) is corrected over 24 to 48 hours. Symptomatic hyponatremia (seizures, lethargy) can be acutely managed with hypertonic saline (3% sodium chloride). The deficit may be calculated to restore the sodium to 130 mEq/L and administered over 48 hours, as follows:

Sodium deficit = (sodium desired - sodium actual) x volume of distribution x weight (kg))

Example: Sodium = 123, weight = 10 kg, assumed volume of distribution of 0.6; Sodium deficit = (130-123) X 0.6 X 10 kg = 42 mEq sodium. Hypertonic saline (3%), which contains 0.5 mEq/mL, may be used for rapid partial correction of symptomatic hyponatremia. A bolus dose of 4 mL/kg raises the serum sodium by 3 mEq/L to 4 mEq/L.

Rapid correction of hypernatremia may result in cerebral edema as a result of intracellular swelling. Osmotic demyelination syndrome, also known as central pontine myelinolytic, can occur as a result of rapid correction of hyponatremia. Symptoms include a headache, confusion, altered consciousness, and gait disturbance, which may lead to respiratory arrest.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Diarrheal diseases and resulting severe dehydration are the leading cause of infant mortality worldwide, especially in children less than 5 years of age.[12] This burden is even higher among children in developing countries. To improve the outcome and decrease the morbidity and mortality from diarrhea diseases, especially rotaviral disease which is the leading cause of death in children, cooperation between various different agencies and countries is needed.

World health organization, while working with member countries and other agencies, promotes national policies and investments to have access to safe drinking water, to improve sanitation, to research diarrhea prevention such as vaccination, to implement preventive measures like source water treatments, safe storage and to help train the health care workers who could go into communities to bring the change at the local level.