Continuing Education Activity

Supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) is a dysrhythmia originating at or above the atrioventricular (AV) node and is defined by a narrow complex (QRS < 120 milliseconds) at a rate > 100 beats per minute (bpm). Atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia (AVNRT), also known as paroxysmal SVT, is defined as intermittent SVT without provoking factors, and typically presents with a ventricular rhythm of 160 bpm. This activity describes the cause, pathophysiology, and presentation of SVT and stresses the importance of an interprofessional team in its management.

Objectives:

- Describe the pathophysiology of SVT.

- Outline the presentation of a patient with SVT.

- Summarize the treatment options for SVT.

- Review the importance of improving care coordination among interprofessional team members to improve outcomes for patients affected by SVT.

Introduction

Supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) is a dysrhythmia originating at or above the atrioventricular (AV) node and is defined by a narrow complex (QRS < 120 milliseconds) at a rate > 100 beats per minute (bpm).

Atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia (AVNRT), also known as paroxysmal SVT, is defined as intermittent SVT without provoking factors, and typically presents with a ventricular rhythm of 160 bpm. [1][2][3]

Etiology

The differential diagnosis includes sinus tachycardia, atrial tachycardia, junctional tachycardia, atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, or multi atrial tachycardia.

In patients susceptible to SVT, medications, caffeine, alcohol, physical or emotional stress, or cigarette smoking can trigger SVT.[4][5]

Epidemiology

The incidence of atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia is 35 per 10,000 person-years or 2.29 per 1000 persons and is the most common non-sinus tachydysrhythmia in young adults. Women have two times higher risk of developing paroxysmal SVT in comparison to men, and older individuals have five times higher compared to a younger person.

SVT is the most common symptomatic dysrhythmia in infants in children. Children with congenital heart disease are it increased risk for SVT. In children younger than 12 years old, an accessory atrioventricular pathway causing reentry tachycardia is the most common cause of SVT. [6][7]

Pathophysiology

The electrical conduction through the heart starts at the sinoatrial (SA), which then travels to the surrounding atrial tissue to the atrioventricular (AV) node. At the AV node, the electrical signal is delayed for approximately 100 milliseconds. Once through the AV node, the electrical signal travels through the His-Purkinje system, which distributes the electrical signal to the left and right bundles, and ultimately to the myocardium of the ventricles. The pause at the AV node allows the atria to contract and empty before ventricular contraction.

The most common cause of SVT is an orthodromic reentry phenomenon, which occurs when the tachycardia is secondary to normal anterograde electrical conduction from the atria to the AV node to the ventricles, with retrograde conduction via an accessory pathway from the ventricles back to the atrial.

A narrow QRS complex (< 120 milliseconds) indicates the ventricles are being activated superior to the His bundle via the usual pathway through the His-Purkinje system. This implies that the arrhythmia originates from the sinoatrial (SA) node, the atrial myometrium, the AV node, or within the His bundle.

In the rarer antidromic conduction, conduction passes from the atria to the ventricles via the accessory pathway, then returns retrograde through the AV node to the atria. [8]

History and Physical

Patients typically present with anxiety, palpitations, chest discomfort, lightheadedness, syncope, or dyspnea. In some cases, a patient may present with shock, hypotension, signs of heart failure, lightheadedness, or exercise intolerance. Some may present without symptoms, and the tachycardia is discovered during routine screening, for example, at pharmacies or with fitness trackers. The onset is typically abrupt and can be triggered by stress secondary to physical activity or emotional stress.

Physical exam, aside from tachycardia, is typically normal in a patient with good cardiovascular reserve. Patients beginning to decompensated may show signs of congestive heart failure, (bibasilar crackles, a third heart sound (S3), or jugular venous distention).

Evaluation

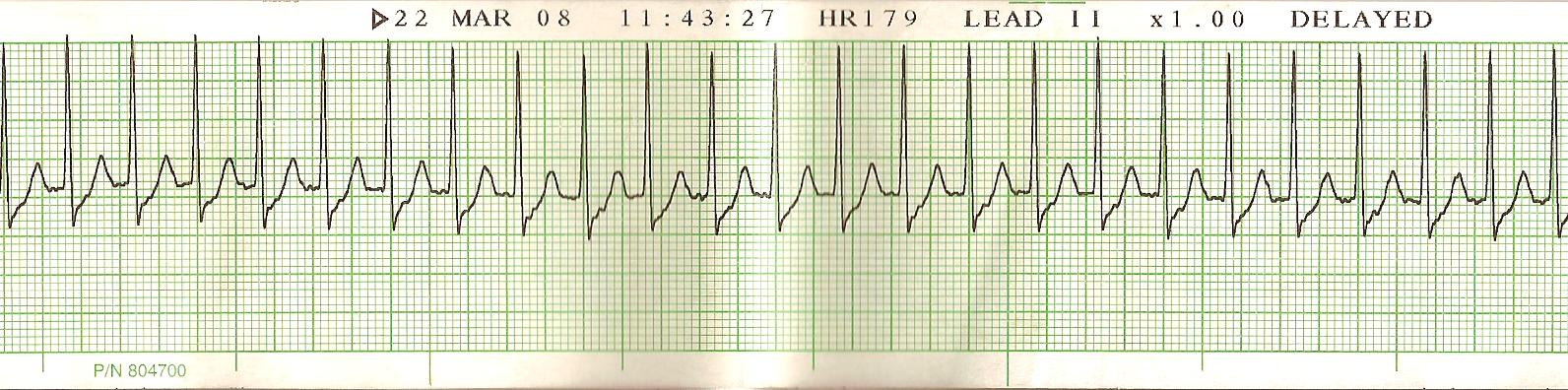

The first test to evaluate for SVT is to obtain an ECG. [9][10][11]

ECG characteristic includes a narrow complex, regular tachycardia with a rate of approximately 180 to 220 beats per minute. P waves are not detectable. If P waves are detectable, consider sinus tachycardia or atrial fibrillation or flutter as a potential etiology.

The remainder of the evaluation is focused on trying to isolate a cause of SVT, for example, electrolyte abnormalities, anemia, or hyperthyroidism. Consider checking a digoxin level of patients using that drug, as SVT can be secondary to supratherapeutic digoxin concentrations.

Treatment / Management

Once an SVT is identified, the next objective is to assess for hemodynamic instability. Signs of hemodynamic instability include hypotension, hypoxia, shortness of breath, chest pain, shock, evidence of poor end-organ perfusion, or altered mental status.[12][13]

If a patient is unstable, consider immediate synchronized cardioversion. It is important that the defibrillator is placed in a sync mode, typically indicated by a marker on the defibrillator screen noting each QRS complex. This mode allows the defibrillator to deliver the shock synchronized with the QRS complex, to prevent the shock from being delivered during the T-wave, while the heart is depolarized. The R on T phenomenon can cause polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. In adults, the starting dose for synchronized cardioversion is 100 joules to 200 joules and can be increased in a stepwise fashion if unsuccessful at lower doses. In children, the first dose for cardioversion is 0.5 J/kg to 1 J/kg and can be doubled to 2 J/kg on subsequent attempts.

In a stable patient, attempted vagal maneuvers while preparing for chemical cardioversion, including the Valsalva maneuver and carotid massage. Both of these act to stimulate the parasympathetic system. This slows impulse formation at the sinus node, slows conduction velocity at the AV node, lengthens the AV node refractory period, and decreases ventricular inotropy.

The Valsalva maneuver is performed expiring against a closed glottis, and needs to be held for 10 seconds to 15 seconds. Patients can achieve this by bearing down as if they are going to have a bowel movement. Younger children can blow out through a syringe or straw. In infants and toddlers, ice packs applied to the face can cause a similar vagal reaction. Although ocular pressure can cause a vagal reaction, it is not recommended as it can lead to a ruptured globe if excessive force is used.

Carotid massage involves placing the patient in a supine position with the neck extended, and applying pressure to one carotid sinus for approximately 10 seconds. Carotid massage is contraindicated in patients with carotid bruit, or who have had a prior transient ischemic attack or cerebral vascular accident in the last three months. Carotid massage is not indicated in children or infants.

The REVERT trial demonstrated that a modified Valsalva maneuver, with the traditional Valsalva maneuver being held for 60 seconds at a 45 degree recumbent position, then being switched to a recumbent position with the legs held at 45 degrees angle for 15 seconds, was more efficacious than the standard Valsalva maneuver. [14]

If vagal maneuvers are ineffective, treat with adenosine. Adenosine is rapidly metabolized in the periphery, and therefore must be given as a rapid push through a large, ideally peripheral, intravenous route. The initial dose is 6 mg intravenously (IV) (pediatric dose 0.1 mg/kg, maximum dose 6 mg). If the initial dose is ineffective, adenosine may be dosed again at 12 mg IVP (pediatric dose 0.2 mg/kg, maximum dose 12 mg). The second dose of adenosine 12 mg IVP may be repeated one additional time if there is no effect. Each dose of adenosine needs to be flushed rapidly with 10 mL to 20 mL normal saline. Often two person administration, with one person administering the adenosine at a proximal IV port, and a second person flushing the IV line via a distal port immediately after adenosine administration, is required to adequate flush in the adenosine.

Consider reducing the adenosine dose to 3 mg IVP if the patient is currently receiving carbamazepine or dipyridamole, is the recipient of a heart transplant, or adenosine is being given through a central line.

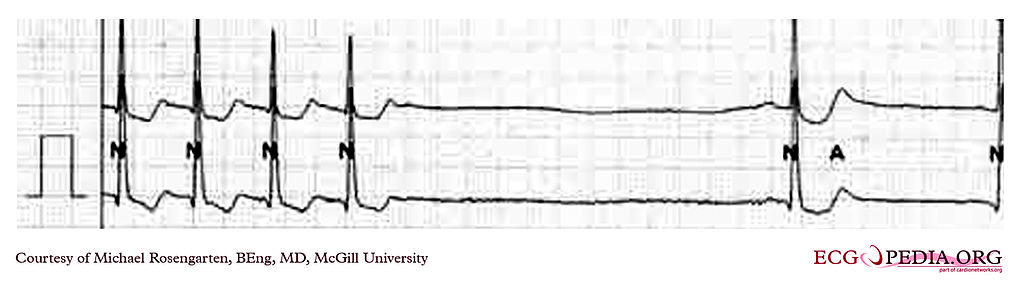

In the event of a patient with a misinterpreted rhythm, the administration of adenosine can help slow down the heart rate long enough to determine if the cause of the patient’s tachycardia is due to a different narrow complex tachycardia (e.g., atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter).

If adenosine fails, second line medications include diltiazem (0.25 mg/kg IV loading dose followed by 5mg/hr to 15 mg/hr infusion), esmolol (0.5 mg/kg IV loading dose, then 0.5 mg/kg/min up to 0.2 mg/kg/min, will need to repeat bolus for every up-titration), or metoprolol (2.5 mg to 5 mg IV every two to five minutes, not to exceed 15 mg over 10 to 15 minutes).

These measures still prove ineffective, overdrive pacing, or pacing the heart at a faster rate than its native rhythm, can help discontinue SVT. However, there is an increased risk of ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation, and therefore should be used with caution and with cardioversion immediately available.

Patients with recurrent SVT without a pre-excitation syndrome may require long-term maintenance with oral beta-blockers or calcium to maintain sinus rhythm. They may also require radio-frequency ablation if an accessory pathway is identifiable. Patients should be counseled on how to perform vagal maneuvers on their own for long-term management of recurrent SVT. [2][15]

Differential Diagnosis

- Atrial flutter

- Atrial tachycardia

- Atrial fibrillation

- Ventricular tachycardia

Complications

Complications are either related to the medications or radiofrequency ablation. Since the latter is an invasive procedure the following complications may occur:

- Hematoma

- Pseudoaneurysm of the artery

- Bleeding

- Myocardial infarction

- Heart block and the need for a pacemaker

- Stroke

- Death

Pearls and Other Issues

Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome is an example of an accessory pathway syndrome, characterized by a short PR interval (< 120 ms), a prolonged QRS (> 100 ms), and a delta wave (a slurred upstroke to the QRS complex). Patients with WPW can occasionally present with an antidromic reentry tachycardia, in which the accessory pathway is the anterograde limb, and the AV node is the retrograde pathway. These typically present with a wide complex, regular, and extremely rapid tachycardia. In these cases, AV nodal blocking agents like adenosine are contraindicated because they can allow unopposed retrograde conduction through the accessory pathway, leading to ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation. Procainamide (15 mg/kg to 18 mg/kg loading dose, 1 mg/min to 4 mg/min maintenance infusion) is the first-line treatment of this tachydysrhythmia, followed by amiodarone (150 mg over 10 minutes, followed by 360 mg over six hours, then 540 mg over 18 hrs). For ventricular rates greater than 250 bpm, consider synchronized cardioversion at 100 J to 200 J.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Paroxysmal SVT is usually managed by an interprofessional team of healthcare workers dedicated to cardiac arrhythmias. Since these arrhythmias cannot be prevented, the focus is on treatment. Besides the cardiologist, the role of the nurse and pharmacist is indispensable. The patient should be educated about this arrhythmia and the potential risk of sudden death if left untreated. For patients with SVT managed with medications, the pharmacist should assist the team by educating the patient on potential adverse effects, drug interactions and the need for close follow-up. The patient should also be educated on the option of radiofrequency ablation, which has a much higher success rate compared to medications. [16](Level II)

Outcomes

For the most part, patients with paroxysmal SVT have a good outcome with treatment. However, a small number of patients with WPW do have a tiny risk of sudden death. In patients with SVT arising due to a structural defect in the heart, the prognosis depends on the severity of the defect, but in healthy people with no structural defects, the prognosis is excellent. Pregnant women who develop SVT do have a slightly higher risk of death if there is an unrepaired heart defect. [17][18][19](Level V)