Continuing Education Activity

Absence seizures are brief seizures during which the patient is unresponsive. They are generally seen in children between 4 and 12 years of age. Absence seizures occur in multiple genetic generalized epilepsies, including childhood absence epilepsy (CAE), juvenile absence epilepsy (JAE), and juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME.) Atypical absence seizures have been reported in up to 60% of patients with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. The condition has a classic EEG finding of a 3 Hz spike and wave discharges. Absence epilepsy is an electroclinical diagnosis (clinical presentation and EEG findings). This activity reviews the evaluation, diagnosis, and management of absence seizures and highlights the differential diagnosis of absence seizures/staring spells.

Objectives:

- Explain how to evaluate a patient presenting for staring spells.

- Identify the first-line medications for absence epilepsy, including some associated side effects.

- Prepare approaches to counsel the family of a patient with newly diagnosed absence seizures.

- Explain how interprofessional team members can collaborate to promptly diagnose, evaluate and treat patients with absence seizures and provide counseling to the patient and their families to enhance patient outcomes.

Introduction

Absence seizures are brief seizures characterized by a behavioral arrest that correlates with generalized 3-Hertz spike-and-wave discharges on electroencephalogram (EEG.)[1] Absence seizures occur in multiple genetic generalized epilepsies, including childhood absence epilepsy (CAE), juvenile absence epilepsy (JAE), and juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME.)[2] Atypical absence seizures have been reported in up to 60% of patients with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome.

Historically, absence epilepsy was known as “pyknolepsy.” This term originates from the Greek term pyknos, which means “very frequent” or “grouped.”[3][4] The term “petit mal” seizure was once used to describe an absence seizure in the past, but it is no longer encouraged.

The International League Against Epilepsy Classification of 2017 defines absence seizures as “generalized non-motor seizures.”[5] However, this term is not entirely precise because, as discussed below, motor manifestations of absence epilepsy are frequently seen.[2]

Etiology

A genetic component exists for all generalized epilepsies and, specifically, for absence epilepsy. In 1951, Lennox reported that 66% of monozygotic twins showed concordance for the EEG pattern of 3-Hertz spike-and-wave. Doose et al. described 252 patients with absence epilepsy with a 3-Hertz spike-and-wave pattern. He proposed that there was multifactorial inheritance. The voltage-gated T-type calcium channel gene, the GABA-A receptor subunits GABRG2 and GABRG3, and the CACNA1A gene are thought to be involved in the etiology of this epilepsy syndrome.[3][6][4]

Also, some copy number variants (CNVs), for example, 15q11.2, 15q13.3, and 16p13.11 microdeletion have also been described in patients with childhood absence epilepsy.[7] However, the mode of inheritance and the majority of genes implicated in CAE are still unknown.[4]

Epidemiology

The incidence of childhood absence epilepsy is approximately 6.3 to 8.0 children per 100 000 per year.[8][9][7]

Childhood absence epilepsy is a common pediatric epilepsy syndrome. Among all cases of epilepsy in school-aged children, 10% to 17% are due to CAE.[1] The age of onset for CAE is typically between 4 and 10 years, with a peak between ages 5 and 7. Girls have CAE more frequently than boys.[4]

Pathophysiology

Although some of the pathways involved in the development of absence seizures have been described, their pathophysiological mechanisms are yet to be fully understood. The cortico-thalamic-cortical circuit is considered to play a significant role in the pathophysiology of absence seizures.[10]

Some of the neurons involved in the cortico-thalamic-cortical system include:

- Cortical glutamatergic neurons originating on cortical layer VI and projecting to the nucleus reticularis of the thalamus

- Thalamic relay neurons with excitatory projections to cortical pyramidal neurons

- Neurons from the thalamic nucleus reticularis containing inhibitory GABA-ergic projections that connect with other neurons from the same nucleus and with thalamic relay neurons; these neurons do not connect directly with the cortex[4]

Neurons from the thalamic nucleus reticularis can fire in an oscillatory pattern (for example, rhythmic bursts involved in the generation of sleep spindles) or continuously in single spikes (tonic firing during wakefulness). Shifts between these two firing patterns in the thalamic nucleus reticularis are modulated by spikes in thalamocortical networks and neurons from the thalamic nucleus reticularis. These are mediated through low-threshold transient calcium channels known as T-type channels. After depolarization, T-type channels briefly allow calcium inflow before becoming inactivated. Reactivation requires a relatively long hyperpolarization facilitated by GABA-B receptors. Therefore, abnormal oscillatory rhythms can originate from T-type channel abnormalities or from increased GABA-B activity.[4]

As explained by the genetics of absence epilepsy, genes coding for T-type calcium channels and for GABA receptors have been associated with the etiopathogenesis of this type of epilepsy. Medications that suppress T-type calcium channels, such as ethosuximide and valproate, are effective anti-absence drugs. Conversely, medications that increase GABA-B activity (e.g., vigabatrin) exacerbate the frequency of absence seizures. In contrast, GABA-A agonists (e.g., benzodiazepines) that preferentially enhance GABA-ergic activity in neurons from the thalamic nucleus reticularis can suppress absence seizures.[4]

More recent research on penicillin-induced models of epilepsy in cats favors the cerebellum's role in long-term electrical stimulation in the absence epilepsy.[11]

History and Physical

The age of onset of CAE is usually between 4 and 10 years, with a peak between the ages of 5 and 7.[4][2] The onset of absence epilepsy before age four should raise concern for an underlying glucose transporter type 1 (GLUT1) deficiency.[4]

Regarding its clinical presentation, family members and teachers usually describe brief spells in which the patient has a loss of awareness, is unresponsive, and has a behavioral arrest. They describe the patient during these spells as having “a blank stare.”[2] Episodes frequently occur, often 10 to more than 30 times throughout the day. Most children stop their activity completely, but some can continue it more slowly or unusually.[1] Some children have 3-Hertz regular eyelid fluttering.[1][2]

Oral automatisms can also occur, especially with prolonged seizures or during hyperventilation. Children frequently have mild clonic or tonic movements in the first few seconds of the spell. Pallor is commonly reported.[1] Urinary incontinence is rare. Spells usually last between 4 and 30 seconds. Hyperventilation, a state of arousal, sleep deprivation, and medication use can affect the duration of the seizure.[1] These seizures are not preceded by an aura and do not have a postictal state.[10]

For JAE, the age of onset is classically between 10 and 19 years, with a peak at 15 years.[4] Seizures are less frequent than in CAE but tend to last longer.[3][4]

Ten to fifteen percent of patients with childhood absence epilepsy have a history of febrile seizures.[11]

On physical examination, hyperventilation can trigger absence seizures. To test this, the examiner asks the child to blow repetitively for more than 2 minutes. Using a pinwheel or paper can be helpful because this encourages the child to cooperate more during testing. If hyperventilation is done successfully, the patient will develop seizures that can be seen clinically and /or on EEG. There is some evidence that absence seizures are more easily provoked when the person is in a sitting position.[12]

Absence status consists of generalized, non-convulsive seizures characterized by impairment of awareness and intermittently has other manifestations such as automatisms or subtle myoclonic, tonic, atonic, or autonomic phenomena. Patients usually have a previous diagnosis of generalized epilepsy. Absence status presents as a non-convulsive seizure lasting between a half hour and several days. It usually ends spontaneously and suddenly but should be treated with anti-seizure medications at the time of diagnosis.[13]

Evaluation

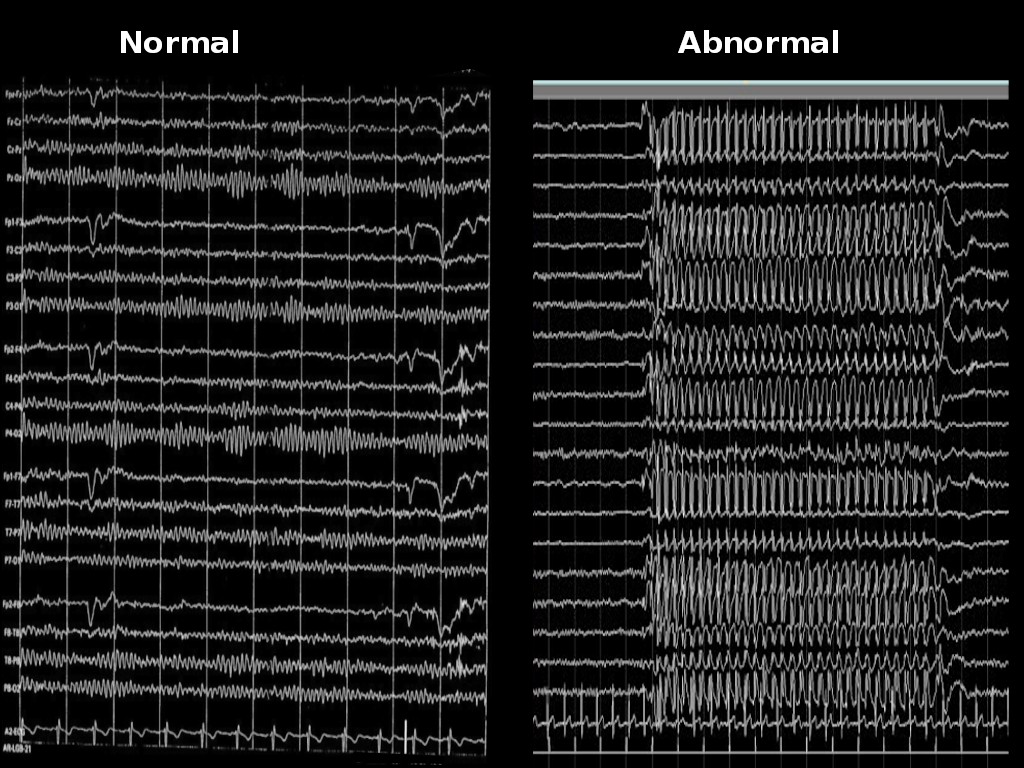

EEG is the main diagnostic tool for the evaluation of absence epilepsy. In the case of childhood absence seizures, EEG shows bilaterally synchronous and symmetrical 3-Hertz spike-and-wave discharges that start and end abruptly. These discharges can sometimes have maximum frontal amplitude or begin with unilateral focal spikes.[2] In 50% of seizures in childhood absence epilepsy, the initial discharge seen has a typical spike-and-wave morphology. The remaining 50% can show a single spike, polyspikes, or an atypical, irregular, generalized spike-and-wave.[1] The background is normal.[4]

Atypical absence seizures show a more insidious onset and offset, slower spike-and-wave paroxysms (less than 3 Hertz), and an abnormal interictal background.[4]

Neuropsychological testing has shown that patients with CAE have cognitive deficits, especially involving attention, executive function, and verbal and visuospatial memory. Difficulty with language and reading is also commonly reported. Depression, anxiety, and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder also have been reported more frequently in patients with CAE.[1]

Since CAE is generalized epilepsy, imaging studies are not performed routinely.

In JAE, EEG demonstrates paroxysms of generalized 3- to 4-Hertz spike-and-wave or polyspike-and-wave discharges.[4]

In the case of absence status, EEG shows continuous or nearly-continuous generalized spike-and-wave or polyspike-and-wave discharges at 2 to 4 Hertz.

Treatment / Management

The first-line treatment for absence epilepsy is ethosuximide. A randomized controlled trial in 2010 that included 446 children with CAE showed that ethosuximide and valproic acid were superior to lamotrigine.[14] However, this study had a low seizure-free rate, with 53% of patients in the ethosuximide group, 58% in the valproic acid group, and 29% in patients taking lamotrigine. The group that received valproic acid had significantly lower scores on attentional measures compared to the ethosuximide and lamotrigine groups. For this reason, ethosuximide is the preferred agent for treating absence epilepsy. A study showed that only one-quarter of children with absence epilepsy became seizure-free with levetiracetam. While effective, levetiracetam can control absence epilepsy at a relatively low dose (usually less than 40 mg/kg/day.)[15]

The most frequent side effects of ethosuximide are abdominal pain and nausea. For this reason, ethosuximide should be taken with meals. Other medications that can be used to manage CAE include valproate, lamotrigine, and topiramate. Second-line medications that can be used as adjunct therapy include valproic acid, zonisamide, and levetiracetam.

It is important to note that some sodium channel blockers like phenytoin, carbamazepine, gabapentin, pregabalin, and vigabatrin can worsen absence seizures.[4]

Women of childbearing age not using contraception should not be treated with valproic acid; the preferred agent is ethosuximide.

Some experts suggest that a ketogenic or a medium-chain triglyceride diet may be beneficial, but strong evidence to support their use is lacking.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for staring spells includes absence epilepsy, focal seizures with alteration of awareness, and non-epileptic paroxysmal events.

Focal epilepsy with alteration of awareness (previously called complex partial epilepsy) can also present with behavioral arrest and automatisms. However, these seizures are usually less frequent than absence seizures. Patients can have generalized seizures with focal epilepsy. The semiology of automatisms can vary depending on the area of the cerebral cortex where the seizures originate.

A study that evaluated non-epileptic staring spells using video-EEG monitoring found that these episodes were often characterized by arrest of all activity, vague facial expressions, and vision fixed on one point without blinking. When the duration of the events was quantified, staring episodes lasted between 3 and 74 seconds. In most children, it was difficult to determine the onset and end of the event. Most parents were unable to regain the child’s attention by waving their hands in front of the child. Other more energetic measures like hand clapping or other loud sounds successfully stopped the events in all children. A significant percentage of children (41%) were inactive at the onset of the stare, and 18% were watching television when the event began.[16]

A retrospective chart review performed in a tertiary care epilepsy center showed that among 276 patients in the epilepsy monitoring unit to have their starring spells monitored, only 11% were deemed to have seizures.[17] Therefore, most staring spells are non-epileptic in nature. Practitioners should be careful when patients present with staring spells and not tell parents or other providers that these episodes are “absence seizures” before EEG evaluation is completed. The study mentioned above developed a tool to determine the pretest probability of seizures in children presenting with staring spells. This tool accounts for patient variables such as results of previous EEG, previous use of antiseizure medications or treatments for psychiatric conditions, and duration of the spells.[17]

Prognosis

Typical childhood absence epilepsy occurs in childhood and resolves by adolescence. Seizure freedom is reported in 57% to 74% of the patients. Patients with generalized tonic-clonic seizures usually do not respond to initial ethosuximide monotherapy and do not achieve long-term remission.

Compared with controls, the risk for accidental injuries during absence seizures is well reported.[16] As mentioned before, these patients have problems in the areas of attention, executive function, and verbal and visuospatial memory. Difficulty with language and reading is also commonly reported. Depression, anxiety, and ADHD have also been reported more frequently in patients with CAE.[1]

Complications

Some activities can be dangerous for people with absence seizures because of the temporary loss of awareness accompanying these episodes. Swimming, operating hazardous machinery, and driving during an absence seizure might result in drowning or an accident. Patients may need to restrict certain activities until their seizures are under control. Some states may also have laws regarding how long a patient must go without a seizure before resuming driving.

Consultations

A general pediatric neurologist or a pediatric epileptologist should be consulted when a patient has staring spells suspected to be seizures. Typically, an outpatient evaluation is a reasonable first step.

Deterrence and Patient Education

As explained above, most staring spells are non-epileptic in nature. When patients present with staring spells, practitioners should explain to caregivers that the differential diagnosis includes seizures, but they should avoid giving a specific diagnosis of “absence seizures” before the EEG evaluation is completed.

Requesting caregivers to take videos of staring spells can be very useful, as this can help characterize them. Event calendars/logs can assist in understanding the frequency, pattern, and possible triggers.

Caregivers of children with CAE should know that generalized tonic-clonic seizures are rare. For this reason, rescue medications such as rectal diazepam and intranasal midazolam are not routinely prescribed. Nevertheless, caregivers should be taught what to do if the child has a generalized tonic-clonic seizure.

Caregivers often assume that, since absence seizures are very brief, they are harmless. Occasionally, they question the need to treat with medications, arguing that the risks could outweigh the benefits. In these situations, we recommend explaining that the child is experiencing frequent episodes of altered consciousness that can increase the risk of accidents. Seizures can also interfere with learning and negatively impact school performance.

Activities like swimming, diving, or rock climbing should only be permitted under supervision.

Driving is not permitted if seizures are not controlled with medications.

Pearls and Other Issues

- Absence epilepsy is primary generalized epilepsy.

- It is classified as a typical or atypical absence, depending on seizure characteristics and EEG patterns.

- Absence seizures are characterized by behavioral arrest and EEG showing 3-Hertz spike-and-wave discharges. Episodes usually occur multiple times per day.

- Absence seizures are seen in several generalized epilepsies, including childhood absence epilepsy, juvenile absence epilepsy, and juvenile myoclonic epilepsy.

- Episodes of behavioral arrest should be called “staring spells” until an EEG evaluation is performed. Patients can only be diagnosed with absence epilepsy if they have characteristic seizure semiology and EEG findings.

- Staring spells can be epileptic or non-epileptic, with the majority being non-epileptic. When episodes are epileptic in nature, they may be due to absence seizures or focal seizures with impaired awareness (complex partial seizures)

- The first-line treatment for absence seizures is ethosuximide. Other therapies include valproate, lamotrigine, and topiramate. Second-line medications that can be used as adjunct therapy include zonisamide and levetiracetam.

- Carbamazepine, phenytoin, gabapentin, vigabatrin, and other medications with similar mechanisms of action can worsen absence epilepsy.

- Approximately 60% of patients with childhood absence epilepsy eventually achieve seizure freedom.

- Lack of response to ethosuximide and the presence of generalized tonic-clonic seizures have been associated with a lack of seizure remission and life-long epilepsy.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

A neurologist should be the lead in managing absence seizures. However, the long-term care and monitoring are done by an interprofessional team that includes the neurologist (child neurologist in the case of the pediatric population), primary care provider, nurse, and pharmacist.

The pharmacist should educate the patient on the importance of medication compliance. In addition, the pharmacist should ask about any adverse reaction at the time of dispensing the medication. The caregiver should be asked if the symptoms are controlled; if not, the pharmacist should communicate with the interprofessional team about the need for a change in the agent used or dosage.

The primary care practitioner, together with the neurologist, should follow up on the liver function tests, amylase, and complete blood count. In addition, birth control should be managed in women taking valproic acid. Finally, drug levels should be monitored periodically as these drugs have a narrow therapeutic index. This is where a pharmacy consult is crucial; the pharmacist can verify dosing, check for drug interactions, and counsel nurses, patients, clinicians, and families regarding potential adverse events. The interprofessional team care model represents the optimal approach to providing care and managing these patients. [Level 5]

A few patients with intractable absence epilepsy may be candidates for the ketogenic diet. If this is the case, a registered dietician with expertise in this diet should be consulted and periodically evaluate the patient.

Finally, mental health providers may be involved in the patient's care as many of these patients develop anxiety, depression, and stress.

Most patients need lifelong follow-up, and the interprofessional team must communicate with each other at any time when there is a change in drug dose, change in drug type, or development of adverse drug reactions.