Introduction

In general terms, abduction, in the anatomical sense, is classified as the motion of a limb or appendage away from the midline of the body. In the case of arm abduction, it is the movement of the arms away from the body within the plane of the torso (coronal plane). The abduction of the arm begins with the arm in a position parallel to the torso and the hand in an inferior position, continues with the movement of the arm to a position perpendicular to the torso, and ends with the movement of the arm so that the humerus is raised above the shoulder joint and points straight upward. (The upper extremity action during a jumping jack can is exemplary of the full range of motion for arm abduction.) The primary muscles involved in the action of arm abduction include the supraspinatus, deltoid, trapezius, and serratus anterior.[1]

Structure and Function

The ability to abduct the arm is a crucial contributor to the full range of motion of the arm. Four different muscles control this action: supraspinatus, deltoid, trapezius, and serratus anterior.[2][3][4][5] The supraspinatus is the primary muscle for the abduction of the arm to 15 degrees. The deltoid controls abduction from 15 to 90 degrees. The trapezius and serratus anterior coordinate with each other and the scapula to facilitate abduction of the arm upwards of 90 degrees.[1]

Embryology

The muscles of arm abduction, like all muscle within the body, except for a few exceptions, is mesodermal in origin during the development of the embryo.[6]

Muscles

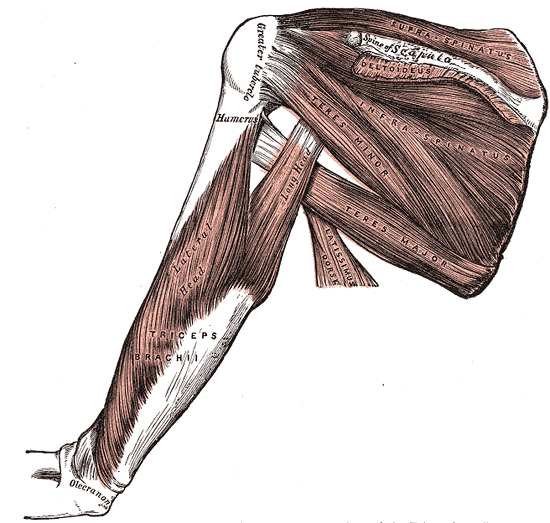

Supraspinatus

The supraspinatus muscle originates from the supraspinous fossa of the scapula, passes under the acromion, and inserts on the superior facet of the greater tubercle of the humerus. It is responsible for the initiation of arm abduction by stabilizing the humeral head in the glenoid fossa and is in control of the motion up to the first 15 degrees of abduction. Past 15 degrees, it assists the deltoid with the abduction of the arm up to 90 degrees. Additionally, the supraspinatus contributes to shoulder joint stability by providing resistance to gravitational forces acting on the joint and maintaining contact between the head of the humerus and the glenoid fossa.[3]

Deltoid

The deltoid, aptly named after the Greek letter delta, is a triangular-shaped muscle found over the glenohumeral joint and is composed of three different heads: anterior, lateral, and posterior. The anterior head originates from the anterior surface of the lateral third of the clavicle. The lateral head originates from the superior surface of the acromion process. The posterior head originates from the posterior border of the spine of the scapula. All heads of the deltoid come together to insert onto the deltoid tuberosity of the humerus. The deltoid is the primary muscle responsible for the abduction of the arm from 15 to 90 degrees. It also serves as a stabilizer of the humeral head, especially in instances of load carrying.[7][2][7]

Trapezius and Serratus Anterior

The trapezius is a large, superficial muscle of the back that divides into three functional parts: descending (superior), middle, and ascending (inferior). The superior fibers of the trapezius originate from the medial third of the superior nuchal line, spinous process of C7, external occipital protuberance, and nuchal ligament; they converge and insert onto the posterior portion of the lateral third of the clavicle. The middle fibers also originate from the spinous process of C7, as well as the spinous processes of T1-T3, and insert upon acromion and the spine of the scapula. The inferior fibers originate from the spinous processes of T4-T12 and converge near the scapula in the form of the aponeurosis. The trapezius functions to laterally rotate, elevate, and retract the scapula. It can also function to extend and laterally flex the neck if the scapula is kept in a fixed position.[5]

The serratus anterior is a saw-shaped muscle originating from the upper eight ribs and inserting upon the inner medial border of the scapula. Its primary function is to laterally rotate and protract the scapula.[4]

The trapezius and serratus anterior muscles work in tandem to coordinate rotation and movement of the scapula to accommodate the full range of motion of the arm. Specifically, they facilitate abduction of the arm from 90 degrees and further upwards.

Clinical Significance

One of the most common reasons for the inability to abduct the arm or pain with the abduction of the arm is a tear of the rotator cuff. The rotator cuff is a group of muscles—supraspinatus, infraspinatus, subscapularis, and teres minor—responsible for the movement and stabilization of the shoulder joint.[8] Of the four muscles found in the rotator cuff, the supraspinatus is the one most frequently torn or injured.[9] As previously mentioned, the supraspinatus is crucial to the initiation of abduction to 15 degrees and assists the deltoid with abduction up to 90 degrees; as such, injury to it would represent a significant obstacle to one’s ability to abduct the arm.[10]

Several physical maneuvers may be used to assess the rotator cuff for possible supraspinatus tear or injury. However, the empty can test is the most commonly utilized assessment for supraspinatus injury. In this test, the patient elevates the arm to parallel the ground and fully internally rotates the arm so that the thumb points downwards; the patient is then asked to resist applied downward pressure. Pain and/or weakness from this action results in a positive test and is indicative of supraspinatus injury.[11]

Scapular winging is another sign that a clinician can check to examine muscles and nerves involved in should abduction.[12] This condition is almost always the result of damage to one of three nerves that control muscles of the upper back, neck, and shoulder girdle:

- Long thoracic nerve- controls serratus anterior

- Spinal accessory nerve - trapezius

- Dorsal scapular nerve - rhomboid muscles

Physical therapists can play an essential role in helping to diagnose and rehabilitate shoulder injuries where abduction is affected. In such cases, they can coordinate their activities with orthopedists, chiropractors, and family clinicians.

Other Issues

The shoulder movements are the integrated response of all the muscles of the body (fixers, facilitators, antagonists, etc.), but in particular, from the proprioceptive information of the elbow.[13]

The first rib in an inspiratory position or the first four dorsal vertebrae can limit the movement of shoulder abduction, as well as all the joints that form the thoracic outlet (clavicle-sternum, clavicle-scapula, rib-sternum, rib-vertebra).