Definition/Introduction

Stereognosis is the ability to identify the shape and form of a three-dimensional object, and therefore its identity, with tactile manipulation of that object in the absence of visual and auditory stimuli. The etymology of the word stereognosis is from the Greek for “stereo,” meaning solid, and “gnosis,” meaning knowledge. A distinction is necessary between manual stereognosis and oral stereognosis, which occurs in the hands and mouth, respectively.[1]

Manual stereognosis requires intact peripheral sensory pathways, namely the dorsal column-medial lemniscus tract (DCMLT), to receive discriminative touch and proprioceptive information. Receival of this information is necessary but not sufficient for stereognosis because it also requires functioning processing centers in the cortex of the parietal lobe.

To properly understand the clinical relevance of stereognosis, one must first appreciate the primary pathway that allows perception of the size and shape of the object, the DCMLT, and how this information is processed in the parietal cortex.

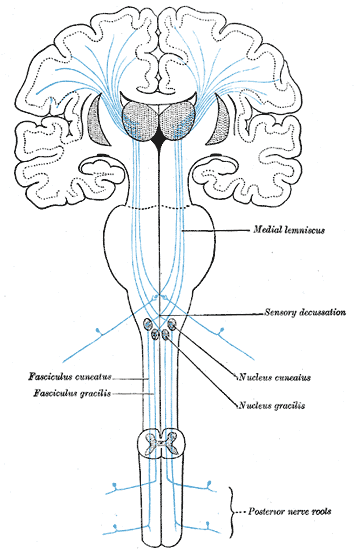

The first-order neurons of the DCMLT have cell bodies in dorsal root ganglia with peripheral processes extending out to sensory receptors (Pacinian corpuscles, Merkel cells, Golgi tendon organs, and muscle spindles) and central processes that enter the spinal cord in the large sensory fiber entry zone of the dorsal horn ascending ipsilaterally in the dorsal columns.[2]

Nerve fibers introduced to the dorsal columns from the lower extremities localize to the medial aspect as they ascend ipsilaterally, forming bundles of axons called the fasciculi gracilis. Similar proprioceptive and discriminative touch information from the upper extremities (spinal level T5 and above) localizes to adjacent lateral axon bundles called the fasciculi cuneatus. The fact that nerve fibers enter the spinal cord and add to the dorsal column fascicles in a medial to lateral manner is an important concept. This somatotopic organization of the ascending tracts allows for precise localization of these stimuli when they eventually reach the primary somatosensory cortex of the parietal lobe.[3]

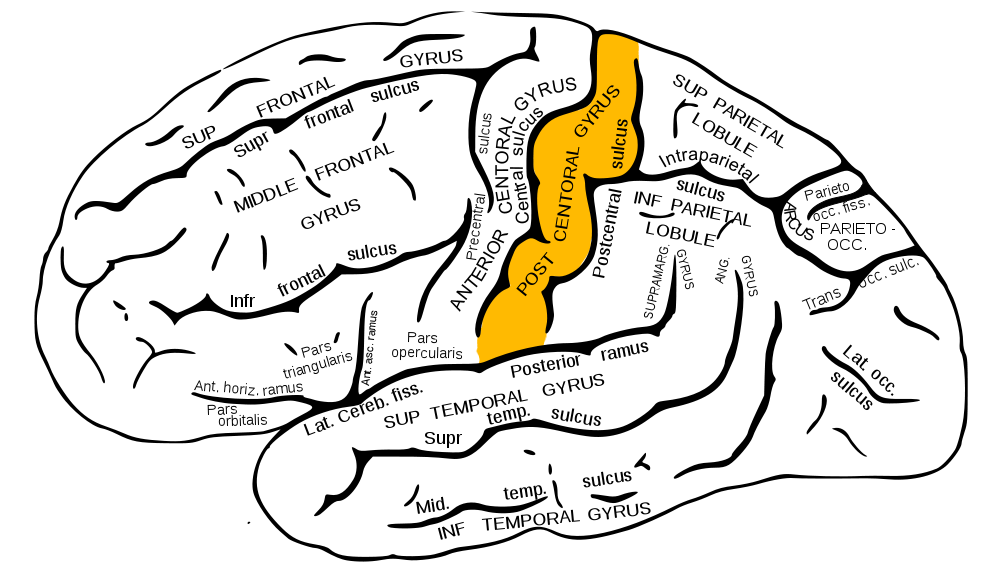

However, before this can occur, the fasciculi cuneatus and gracilis must ascend ipsilaterally until they reach the caudal medulla. As these axon bundles enter the caudal medulla, the neurons synapse in their respective nuclei; the nuclei cuneatus and nuclei gracilis. Second-order neurons of the DCMLT decussate, or cross over, in the caudal medulla forming crossing tracts termed the internal arcuate fibers. This is an important anatomic process that explains why the interpretation of right-sided discriminative touch information is via the left somatosensory cortex and vice versa. After decussation, the internal arcuate fibers are now referred to as the medial lemnisci and travel through the pons and midbrain until reaching the thalami of the diencephalon. Here, second-order neurons synapse with third-order neurons in the ventral posterolateral nuclei of the thalami. Third-order neurons from each tract pass through their respective internal capsule en route to the primary somatosensory cortices of the anterior parietal lobes, located in the postcentral gyri.[2][4][5]

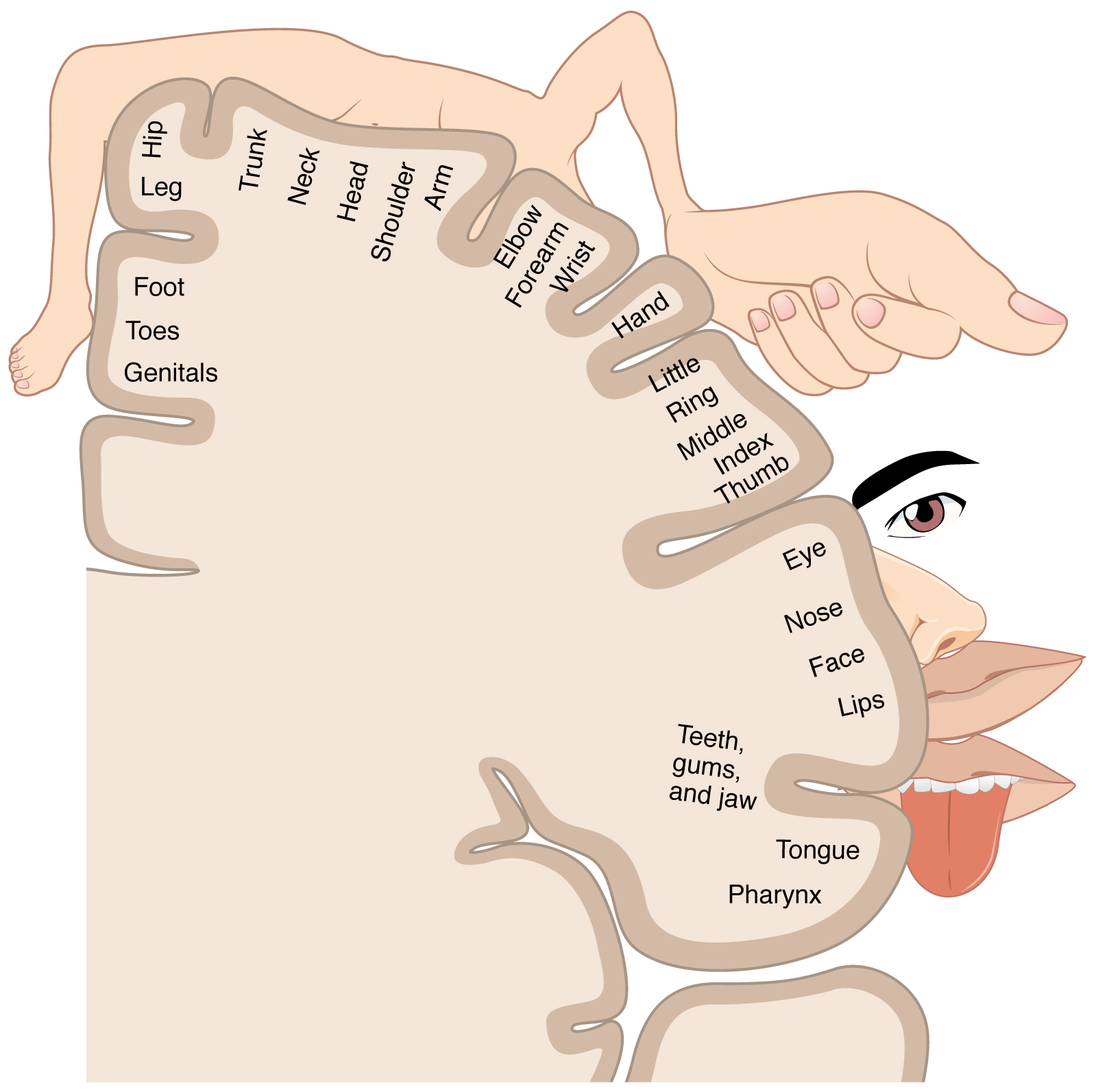

The organization of the primary somatosensory cortices of the parietal lobes is in a somatotopic manner such that the inferior anatomic structure information (from the lower extremities) is interpreted in the superomedial aspect of the postcentral gyrus, and the more superior anatomic structure information (from the face and arms) is interpreted in the lateral aspect of said gyrus. This organization's representation is as a diagrammatic homunculus overlying the precentral gyrus with areas of the body being displayed in their appropriate location along the gyrus and the anatomic structure size being proportional to their relative tactile sensitivity. During manual stereognosis, information from the hand portion of the primary somatosensory cortex is sent to the tertiary somatosensory association cortex located in the superior parietal lobule. Localization of stimuli and integration of information within this cortical processing area represents the physiologic basis for stereognosis.[6]