Definition/Introduction

Change is inevitable in healthcare. A significant problem specific to healthcare is that almost two-thirds of all change projects fail for many reasons, such as poor planning, unmotivated staff, deficient communication, or widespread changes[1]. All healthcare providers, from the bedside to the boardroom, have a role in ensuring effective change. Using best practices derived from change theories can help improve the odds of success and subsequent practice improvement.

Suppose a healthcare provider works in a hospital department that has experienced a 3-month increase in unwitnessed patient falls during shift change hours. Evidence-based changes in the current shift change process would likely decrease patient falls; however, departmental leadership has attempted unsuccessfully to fix this problem twice in the past 3 months. Staff continues to revert to previous shift change protocols to save time, which leaves patients unmonitored for extended periods. What can departmental leadership and staff do differently to create sustained, positive change to serve the department’s patients and employees?

The answer may lie within the work of several change leaders and theorists. Although theories may seem abstract and impractical for direct healthcare practice, they can be quite helpful for solving common healthcare problems. Lewin was an early change scholar who proposed a 3-step process for ensuring successful change[2]. Other theorists like Lippitt, Kotter, and Rogers have added to the collective change knowledge to expand upon Lewin’s original Planned Change Theory. Although each change theory has unique strengths and weaknesses, the theories’ commonalities can provide best practices for sustaining positive change (See Image. Change Management).

Lewin’s Theory of Planned Change includes the following change stages:

- Unfreezing: Understanding change is needed

- Moving: The process of initiating change

- Refreezing: Establishing a new status quo [2]

Lippitt, building on Lewin’s original theory, created the Phases of Change Theory that encompass the following change phases:

- Becoming more aware of the need for change

- Developing a relationship between the system and the change agent

- Defining a change problem

- Setting change goals and action plans for achievement

- Implementing the change

- Staff accepting the change; stabilization

- Redefining the relationship of the change agent with the system [3]

Kotter’s 8-Step Change Model, created in 1995, includes the following change management:

- Create a sense of urgency for change

- Form a guiding change team

- Create a vision and plan for change

- Communicate the change vision and plan with stakeholders

- Remove change barriers

- Provide short-term wins

- Build on the change

- Make the change stick in the culture [3]

Finally, Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovation Theory introduced these 5 change phases[4]:

- Knowledge: Education and communication to expose staff to the change

- Persuasion: Use of change champions to pique staff interest; peers persuading peers

- Decision: Staff decide whether to accept or reject the change

- Implementation: Putting new processes into practice

- Confirmation: Staff recognize the value and benefits of the change and continues to use changed processes [4]

Issues of Concern

All change initiatives, no matter how big or small, unfold in 3 major stages: pre-change, change, and post-change. Within those stages, healthcare providers working as change agents or change champions should select actions that match change theories. One of the most critical aspects of pre-change planning is involving key stakeholders in problem identification, goal setting, and action planning. Involving stakeholders in change planning increases staff buy-in. These stakeholders should include staff from all shifts, including nights and weekends, to create peer change champions for all shifts[5].

One particular portion of Rogers’ change theory identifies the various rates with which staff members accept changes through innovation diffusion. During pre-change planning, change agents should assess their departmental staff to determine which staff belong to each category. Rogers described the different categories of staff as innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards.[4] He further qualified those change acceptance categories with the following descriptions:

- Innovator: Passionate about change and technology; frequently suggests new ideas for departmental change.

- Early adopter: High levels of opinion leadership in the department; well-respected by peers

- Early majority: Prefer the status quo; willing to follow early adopters when notified of upcoming changes

- Late majority: Skeptical of change but eventually accepts the change once the majority has accepted; susceptible to increased departmental social pressure

- Laggard: High levels of skepticism; openly resist change [4]

Most departmental staff likely belongs to the early or late majority. Change agents should focus their initial education efforts on Innovator and Early Adopter staff. Early adopters are often the most pivotal change champions, persuading early and late majority staff to embrace change efforts[4].

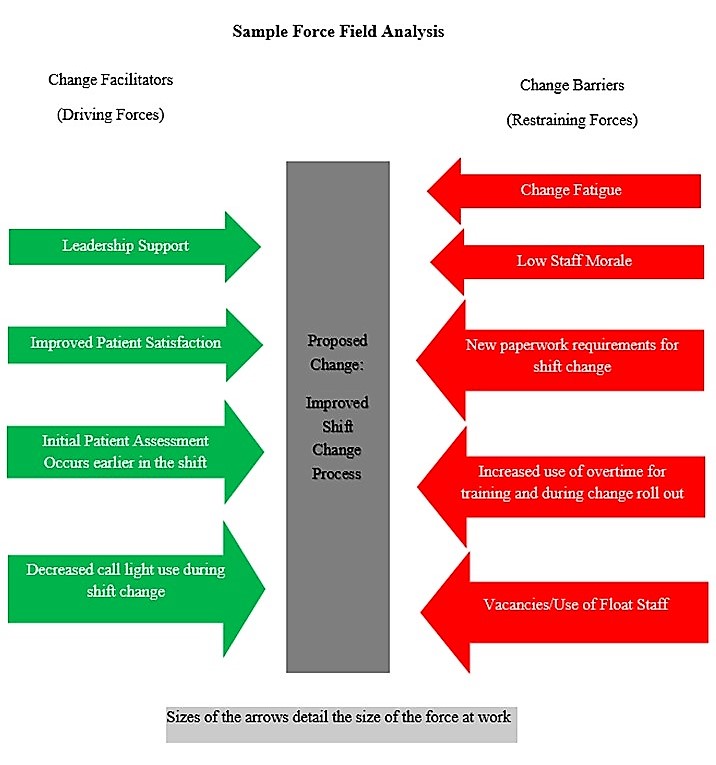

One final critical assessment change leaders should incorporate is a force field analysis, a significant component of Lewin’s early change theory. A force field analysis involves a review of change facilitators and barriers at work in the department. Change leaders should work to reduce change barriers through open communication and education while also aiming to strengthen change facilitators through staff recognition and various incentives.

One of the biggest mistakes a change leader can make during change implementation is failing to validate that staff members perform new processes as planned. Ongoing leader engagement throughout change execution increases the chances of success.[5] Staff resistance remains common during this stage. Change leaders may find conducting another Force Field Analysis during this changing phase helpful to ensure no new barriers have emerged.[3] Further strengthening of change facilitators through staff engagement, recognition, and sharing short-term wins help maintain momentum. As the change process continues, staff may require additional on-the-spot training to overcome knowledge deficits. Finally, leaders must continue to monitor progress toward goals using information like patient satisfaction, staff satisfaction, fall rates, and chart audits.[3]

Once the change has become part of the department’s new culture, change leaders must periodically validate departmental processes and solicit staff feedback. Change agents can redefine their relationship with the staff to take on a less active role in the change maintenance process. However, once the change leader begins to release control over the change process, staff members may slowly revert to old, negative behaviors. Periodic spot-checking and continued data monitoring can solidify the change as the department’s new status quo. Change managers should celebrate wins with staff while continuing to share evidence of success in staff meetings or with departmental communication boards.[5]

Clinical Significance

Change is inevitable, yet slow to accomplish. While change theories can help provide best practices for change leadership and implementation, their use cannot guarantee success. The process of change is vulnerable to many internal and external influences. Using change champions from all shifts, force field analyses, and regular supportive communication can help increase the chances of success.[5] Knowing how each departmental staff member will likely respond to change based on the diffusion of innovation phases can also indicate the types of conversations leaders should have with staff to shift departmental processes.