Continuing Education Activity

Dysbaric osteonecrosis is a type of avascular necrosis of the bone that is most commonly found in undersea divers and workers that breathe compressed air or gas. This condition can lead to increased risk of fractures and of total joint arthroplasty. The most commonly involved region is the hip joint, specifically the proximal femur, with bilateral involvement not being uncommon. This activity describes the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of dysbaric osteonecrosis and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the management of these patients.

Objectives:

- Outline the pathophysiology of dysbaric osteonecrosis.

- Describe the presentation of a patient with dysbaric osteonecrosis.

- Summarize the treatment and management options available for dysbaric osteonecrosis.

- Explain interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance the treatment of dysbaric osteonecrosis and improve patient outcomes.

Introduction

Dysbaric osteonecrosis is a type of avascular necrosis of the bone most commonly found in undersea divers and workers breathing compressed air or gas. This condition can lead to increased risk of fracture depending on the location and size of the bony defect. The rate of receiving total joint arthroplasty is increased in this patient population as well. The most commonly involved region is the hip joint, specifically the proximal femur, with bilateral involvement not being uncommon.

Etiology

Although not entirely understood and having multiple theories of etiology, dysbaric osteonecrosis is commonly thought to result as a long-term manifestation of sub-clinical decompression sickness (DCS). During decompression, gas dissolved in the arterial blood comes out of solution and can form arterial gas emboli. Gas bubble formation can lead to endothelial disruption and subsequent vascular occlusion via coagulation of intraosseous microcirculation. This leads to venous thrombosis causing retrograde arterial flow and increasing the overall intraosseous pressure. When specifically examining a high-risk region such as the proximal femur, subsequent avascular necrosis of the femoral head can lead to chondral microfracture and eventual collapse.[1]

Epidemiology

The incidence of dysbaric osteonecrosis is highly variable which is likely a result of its insidious nature and the logistical difficulty of thoroughly screening high-risk individuals. In various Japanese studies, the incidence has been seen as high as 50% of Japanese commercial divers, while the US Navy reports only a 2.5% in military divers. There is a strong association with increased frequency and length of time exposed to compressed air and gas. Overall, the incidence is higher in males given the proportion of males employed in fields that involve exposure to breathing compressed gases. This is also consistent with the fact that the incidence of avascular necrosis from all causes is more common in men as well. Multifocal disease is prevalent, and the average age at presentation is 30 to 50 years.[2]

Pathophysiology

Disruption of the bone's blood supply leads to necrosis, demonstrated by an absence of osteocytes in the lacunae. Lesions proximal to an articular surface commonly lead to a flattening of the surface and are more prone to collapse. Subchondral fractures may be evident. There is potential for revascularization, which leads to granular tissue permeating the necrotic trabeculae and increasing strength.

Histopathology

Histologic evidence of empty osteocytic lacunae is consistent with osteonecrosis. When evaluating early necrosis, there may be a loss of nuclear staining of marrow cells and the appearance of large, ovoid, fat-containing spaces appear. Small vessels will show evidence of necrosis. An increased amount of foamy histiocytes and woven bone may be present as well.[3]

History and Physical

Juxta-articular lesions in the hips and shoulders are the most likely to become symptomatic. The patient may have increased pain on movement and weight bearing which could end up resulting in the collapse of the articular surface or fracture. The patient may report pain that radiates from the joint down the limb as well as restriction of the range of motion. Non-articular lesions commonly occur in the femoral and humeral shafts and are much less likely to become symptomatic as they rarely involve the cortex or lead to pathologic fracture. A thorough orthopedic examination focusing on the joints is merited, and other causes of bony lesions (including malignancy in addition to other etiologies of osteonecrosis) explored given the relatively uncommon nature of this condition. Specific attention should be paid to whether or not the patient has functional pain.

Evaluation

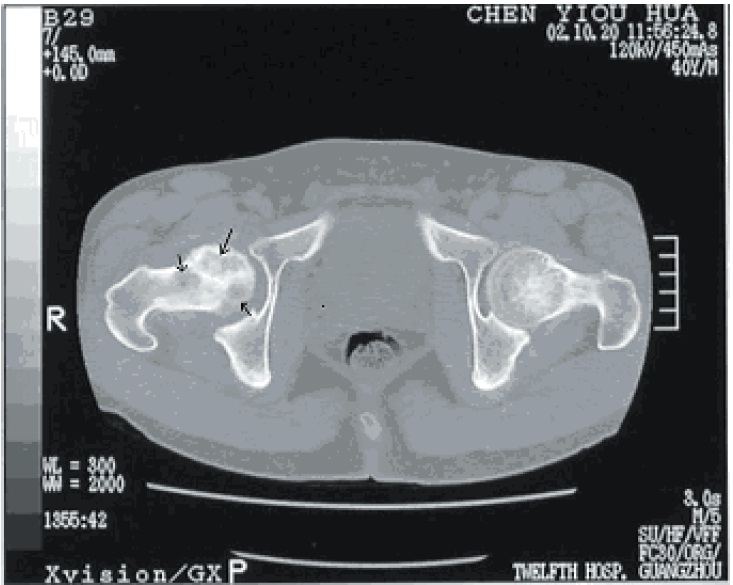

In light of the appropriate patient history and physical, x-rays are the initial study of choice. MRI is useful to characterize the nature of any lesions as well. Also, if a lesion is detected and there is a high index of suspicion in light of negative MRI, bone scintigraphy or single positron emission computed tomography are being used increasingly due to reported high specificity. CT scans are useful in their ability to further elucidate bony anatomy and aid in preoperative planning depending on the specific scenario.

Treatment / Management

Management of dysbaric osteonecrosis is complex as it varies significantly depending on the location and specific characteristics of the lesion. After being first identified, osteonecrotic lesions are typically observed radiologically to monitor for any changes or potentially self-resolution. Once any bony lesion is identified, the patient should be referred to an orthopedic surgeon. Special attention should be paid to large lesions in the diaphysis of the femur or tibia that are accompanied by a significant amount of pain with ambulating. The patient should be provided with crutches or another form of assistive device and be made non-weight bearing until they have received a prompt evaluation by an orthopedic surgeon due to the concern of pathologic fracture. Significant lesions of the long bones such as the humerus, femur, and tibia may receive prophylactic intra-medullary nailing to prevent this from occurring. Symptomatic lesions in other anatomic reasons can sometimes be treated with curettage and bone grafting. In regards to the proximal femur, treatment can become increasingly complex depending on the stage of the disease. Necrosis of the proximal femur in Ficat stage 0-II can potentially benefit from oral bisphosphonate treatment to prevent femoral head collapse. Small, early lesions have multiple surgical options including core decompression with or without bone graft (alleviating intraosseous hypertension and stimulating angiogenesis), rotational osteotomy away from the weight-bearing surface, and vascularized, free-fibular, strut grafting in young patients. Total hip arthroplasty is indicated in patients over 40 with significant hip joint arthrosis or in younger patient's with more advanced femoral head collapse or at minimum a present crescent sign (Ficat stage 3).

Differential Diagnosis

Diagnoses to consider include:

- Malignancy

- Nonpathologic fracture

- Other causes of osteonecrosis: Sickle cell, systemic lupus, erythematosus, viral causes, HIV medication, irradiation, hematologic diseases, marrow-substituting diseases such as Gaucher's, alcoholism, steroid use, hypercoagulable states

Staging

There is no specific staging system for dysbaric osteonecrosis itself. However, the Ficat classification as below is utilized when staging osteonecrosis of the proximal femur.[4]

- Stage 0: Normal x-ray, normal MRI, no symptoms

- Stage 1: Normal or minor osteopenia on x-ray, edema on MRI, increased uptake on bone scan, pain in the groin

- Stage 2: Mixed osteopenia/sclerosis on x-ray, a defect on MRI, increased uptake on bone scan, groin pain and stiffness on exam

- Stage 3: Presents with "crescent" sign or some cortical collapse on x-ray, MRI has same findings as x-ray, Increased uptake on bone scan, patient has pain radiating to knee and walks with a limp

- Stage 4: X-ray shows end-stage collapse with secondary arthrosis of the hip joint, MRI shows similar findings as x-ray, bone scan shows increased uptake, patient presents with pain and a limp.

Prognosis

Prognosis is variable and specific given the location of the lesion, size, and age/functional status of the patient. Patients with small lesions not involving major joints may be asymptomatic, and patients with large juxta-articular lesions may have a poor overall prognosis and functional status without significant surgical intervention.

Pearls and Other Issues

- Rule out other causes of osteonecrosis

- Look for lesions in other bones

- Refer to an orthopedic surgeon

- Obtain MRI when clinical suspicion is high, but standard radiographs are unimpressive

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

the management of dysbaric osteonecrosis involves an interprofessional team including an orthopedic nurse. As soon as the diagnosis is suspected, weight bearing on the affected joint should be reduced and an orthopedic consult made.[5] The management depends on the location of joint affected, size of lesion, patient age and other comorbidities. Small lesions may heal with time but large lesions lead to severe disability even following treatment. Many types of orthopedic procedures have been developed to treat osteonecrosis, but none is ideal and success cannot be guaranteed. [6]