Continuing Education Activity

Elderly patients with head trauma represent a large proportion of patients seeking medical attention. There are special considerations and challenges when evaluating and treating these patients. A multidisciplinary approach is necessary to treat geriatric head trauma patients adequately.

Objectives:

- Describe the epidemiology of head trauma in the elderly.

- Analyze the risk factors that make elderly patients uniquely susceptible to traumatic injuries.

- Review the treatment options in managing a patient taking coumadin presenting with a traumatic head injury.

- Explain the importance of collaboration and communication with the patient, their families, and multidisciplinary medical teams in treating traumatic head injury in elderly patients.

Introduction

Trauma is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality among older patients. Head trauma in the elderly represents a particularly challenging subset of cases in patients with trauma. Elderly patients tend to have a higher number of chronic medical conditions, which increases the risk of death in traumatic injuries.[1] When compared to younger patients, elderly patients with traumatic head injuries were much more likely to die or require long term care.[2]

Etiology

Patients older than 60 years old are a growing demographic in the developed world and are at higher risk for traumatic injury. The definition of "elderly" or "geriatric" is a controversial topic. Many articles base the definition of "geriatric" at age 65, but for the most part, this does not have a basis in evidence-based medicine. Age 65 is commonly used as a default; however, evidence supports that a patient's preexisting conditions and comorbidities may be a better predictor of long term complications secondary to trauma.[3] These comorbidities in older patients make them more susceptible to falls, such as in unilateral weakness secondary to stroke. Also, elderly patients commonly take more medications, which can precipitate falls, cause confusion, or worsen bleeding. For example, aspirin or even more potent forms of anticoagulation, such as coumadin, can drastically worsen traumatic intracranial bleeds. These chronic conditions compounded by the effects of polypharmacy cause elderly patients to have less capacity to compensate for traumatic injuries.

Epidemiology

Falls are the most common etiology of traumatic injury.[4] Research has revealed that elderly patients older than 65 years old have about a 27% chance of fall in any given year.[5] Most of the falls in the geriatric population tend to be ground-level falls, which would otherwise be benign in younger patients.

The second most common cause of traumatic injury is motor vehicle collisions. While these cases are less common than falls, motor vehicle collisions are more likely to cause mortality in older patients. Geriatric patients who sustain high energy trauma are three times more likely to die when compared to younger patients.[6]

Pathophysiology

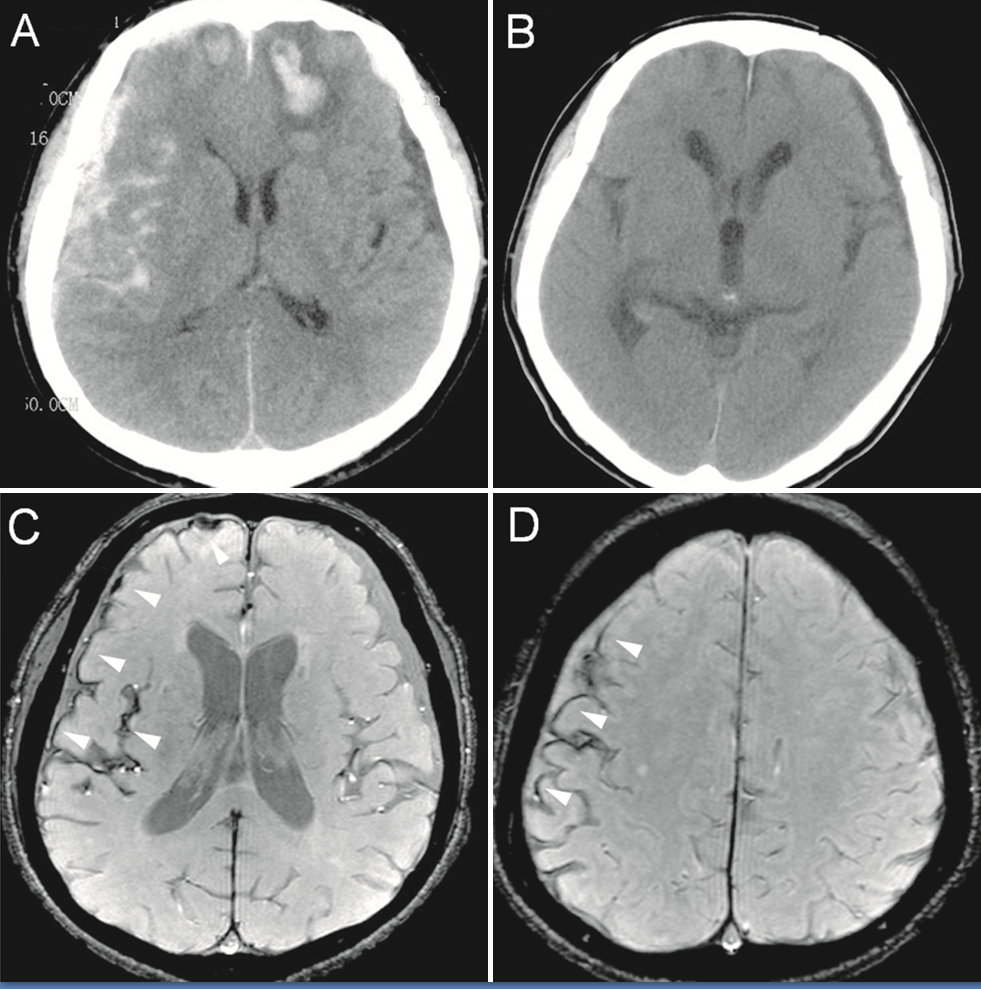

Anatomical changes that come with aging affect the pathophysiology of head trauma in the elderly. When compared to a younger population, subdural hematomas (along with intraparenchymal hemorrhages) are the most common types of intracranial bleeds.[7] This difference is explainable by the increased adherence of the dura to the skull in elderly patients. Subsequently, the underlying bridging veins in the elderly are more likely to be damaged in head trauma. As the bridging veins bleed within the skull, intracranial subdural hematomas form as opposed to epidural hematomas, which occur more commonly in younger patients.

Also, advancing age often leads to progressive brain atrophy leaving more room for increased bleeding for the subdural hematoma within the cranial cavity.[7] This situation leads to delayed onset of symptoms, which may cause elderly patients to seek care later. Delay in presentation and subsequent delays in initiation of treatment contribute to the higher morbidity and mortality in the elderly.

The higher incidence of chronic dementia in the elderly may also cause delays in presentation and treatment. Obtaining an accurate history and physical exam in an elderly patient with dementia can be particularly challenging.

A subset of the elderly population that requires special consideration are the patients on anticoagulation. A variety of medical conditions such as atrial fibrillation, pulmonary embolism, or deep vein thrombosis require the use of anticoagulation medications. These conditions become increasingly common as the population ages. In fact, as high as 10% of the elderly patients presenting with trauma are on coumadin.[8] Coumadin is the most commonly used anticoagulant, but the use of newer direct oral anticoagulant medications such as dabigatran is rapidly increasing. All of these medications increase the amount and rate of bleeding, which would increase the chance of long term disabilities and the possibility of death.[9]

History and Physical

The initial evaluation of a geriatric patient begins with the standard trauma primary survey of the airway, breathing, circulation, disability, etc. Supportive immediate resuscitative care such as intubation may be required to stabilize the patient before a thorough evaluation of potential head trauma can be started. Then, a detailed history is necessary to determine if head trauma has occurred. An occult presentation of head trauma is much more likely to be present in geriatric patients.[10] Unconscious patients, those with dementia, or who present with altered mental status may not be able to give an adequate history. In that case, the history should be obtained from multiple sources such as family, friends, bystanders, EMS as well as the patient him or herself. Any report of possible syncope by the patient or other witnesses warrant consideration for potential traumatic injury.

Besides a history that explicitly states a traumatic head injury has occurred, other significant historical factors that may indicate a traumatic head injury are headache, nausea/vomiting, changes in vision, decreased sensation, weakness, and reported confusion.

A thorough examination of older patients with traumatic injuries is of particular importance. Subtle bruising may be the only indication of traumatic injury, especially in demented patients with non-specific complaints. On the other hand, the physical examination is often less reliable with older patients. Acute focal neurological deficits may be difficult to differentiate from chronic neurological findings. Even the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) has been found to be less accurate when assessing older patients with a traumatic head injury.[11] Also, geriatric patients may experience more difficulty in localizing their pain on examination, which may obscure significant physical findings in these patients.[12]

Furthermore, signs of increased intracranial pressure should also undergo evaluation when head trauma is suspected. These include abnormal pupillary responses, decorticate or decerebrate posturing, seizures, and the classic "Cushing Triad" (hypertension, bradycardia, irregular respirations).

Evaluation

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the head is the imaging test of choice when evaluating a significant head trauma. Given the elderly population's comorbidities, frequently inadequate history, and a potentially unreliable physical examination, essentially all of these patients with head injury require a CT scan of the head. Clinical decision rules were developed to guide physicians regarding which patients need a CT head to rule out clinically significant head trauma. These decision criteria serve to rule out clinically significant head trauma without a CT scan of the head. However, the three most widely accepted decision rules all acknowledge that in the elderly patient population, clinically significant head trauma cannot be ruled out based on history and physical examination alone. The Canadian CT head rules and the Nexus II rules place this age at 65 years old while the New Orleans rules place the age at 60 years old.

Diagnosis of clinically significant head trauma such as an intracranial bleed does not require any laboratory testing. However, labs and other studies are necessary to assess for any underlying medical conditions that may have precipitated the traumatic injury in the first place such a syncope (i.e., EKG, chest radiographs, urinalysis, basic labs, cardiac enzymes, etc.) in addition to help facilitate potential surgical intervention if the diagnosis of a head bleed is confirmed. In particular, PT/INR requires examination in patients taking coumadin with a significant head injury in preparation for possible coumadin reversal. While there is no specific test to evaluate novel direct oral anticoagulation (NOAC) efficacy, thromboelastogram can help direct reversal.

Treatment / Management

If meeting specific criteria, cases of intracranial bleed such as epidural hematoma, subdural hematoma, or intracerebral hemorrhage often require surgical intervention. Prompt consultation with a neurosurgeon is required to make the determination. Often burr hole placement and/or craniectomy is the definitive treatment for these intracranial bleeds.

Blood pressure management is required to prevent hypotension. Normal saline is preferred to achieve euvolemia when compared to dextrose or balanced crystalloid solutions such as lactated Ringer's solution in cases of traumatic brain injury to prevent cerebral edema.[13]

Airway management, such as intubation, may be necessary for airway protection and to prevent hypoxia.

Seizures and seizure prevention are often indicated in traumatic brain injury. Up to 1 in 5 patients have been found to develop a seizure after moderate to severe head injuries during the first week after traumatic brain injury. Levetiracetam has become the medication of choice in the treatment and prevention of traumatic seizures.

Treatment of increased intracranial pressure includes keeping the head of the bed raised to 30 degrees and maintaining the neck in a neutral position. Osmotic therapy using IV hypertonic saline or mannitol can be a consideration in consultation with neurosurgery.

In patients taking coumadin, the INR should be normalized as soon as possible using prothrombin complex concentrate and vitamin K. If prothrombin complex concentrate is not immediately available, fresh frozen plasma should be started to facilitate coumadin reversal.

Differential Diagnosis

Other conditions may cause similar symptoms to traumatic brain injury in the elderly. Non-traumatic intracranial bleeds such as non-traumatic subdural hematomas, intraparenchymal hemorrhages, subarachnoid hemorrhages may present with similar symptoms of headache, altered mental status, or focal neurological deficits on the exam. Ischemic strokes may also mimic signs and symptoms of traumatic brain injury.

Prognosis

Elderly patients (ages 60 to 99) with severe head trauma (defined as a Glasgow Coma Scale less than 9) have a greater than 80% chance of death and/or long term disability.[2]

Complications

Survivors of traumatic brain injury may suffer from chronic neurological complications. Seizures are a common long term complication after brain injury as well as varying degrees of cognitive impairment. Focal weakness or sensory deficits may also occur.

Deterrence and Patient Education

As mentioned previously, the most common causes of geriatric trauma are falls and motor vehicle collisions. Strategies to prevent these occurrences will serve to decrease the incidence of geriatric head injuries. Fall prevention is paramount, and patient education can be crucial. Ambulation assistance devices such as canes, walkers, and eventually wheelchairs can help prevent falls. Other simple strategies such as rug removal to avoid trips and falls in the home can also be employed. To prevent motor vehicle collisions, physicians must be vigilant to assess for medical conditions that would preclude elderly patients from safely operating a motor vehicle. Impaired vision, seizures, syncopal episodes, and polypharmacy can significantly impair the young and old alike from safe driving.

In patients that might require anticoagulation, a thorough discussion on the risk and benefits of anticoagulation is necessary. This discussion will allow the patient and their family to make an informed personal decision to see if anticoagulation will fit into their lifestyle.

Pearls and Other Issues

Elderly patients are a particularly vulnerable trauma population. They are at particular risk of injury and prolonged recovery associated with a myriad of complications.

In particular, elderly patients on anticoagulation should be given special attention with a low threshold for injury suspicion.

An interprofessional team approach should be in place to keep patients out of the hospital, co-manage care once in the hospital, as well as for post-hospitalization recovery planning.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Interdisciplinary collaboration is essential in providing medically appropriate and compassionate care to elderly patients. Physicians and nursing have to work with not only the patient but often the patient's family and friends to determine the best course of action. Also, social workers and spiritual professionals can be invaluable in such cases. As a result, palliative care often becomes the primary focus of treatment in these elderly patients.