Continuing Education Activity

Peptic ulcer disease refers to an insult to the mucosa of the upper digestive tract resulting in ulceration that extends beyond the mucosa and into the submucosal layers. Peptic ulcers most commonly occur in the stomach and duodenum though they can occasionally be found elsewhere (esophagus or Meckel diverticulum). While the majority of peptic ulcers are initially asymptomatic, clinical manifestations range from mild dyspepsia to complications including gastrointestinal bleeding, perforation, and gastric outlet obstruction. This activity will provide a brief overview of peptic ulcer disease with a primary focus on the complexity of perforated peptic ulcers from an emergency medicine perspective and also highlights the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and improving care for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Describe the pathophysiology of peptic ulcer disease.

- Outline the presentation of a patient with a perforated peptic ulcer.

- Summarize the treatment options for perforated peptic ulcers.

- Explain the importance of care coordination among interprofessional team members in order to improve outcomes for patients affected by perforated peptic ulcers.

Introduction

Peptic ulcer disease is defined as an insult to the mucosa of the upper digestive tract resulting in ulceration that extends beyond the mucosa and into the submucosal layers. Peptic ulcers most commonly occur in the stomach and duodenum though they can occasionally be found elsewhere (esophagus or Meckel diverticulum).[1] While the majority of peptic ulcers are initially asymptomatic, clinical manifestations range from mild dyspepsia to complications including GI (gastrointestinal) bleeding, perforation, and gastric outlet obstruction. Peptic ulcers may be either duodenal or gastric in location. This article will provide a brief overview of peptic ulcer disease with a primary focus on the complexity of perforated peptic ulcers from an emergency medicine perspective.

Etiology

Peptic ulcer disease was traditionally thought to be the result of increased acid production, dietary factors, and even stress. However, Helicobacter pylori infection and the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) including low-dose aspirin are now the more popular etiologies leading to the development of peptic ulcer disease.[1][2][3] Other factors such as smoking and alcohol may also contribute.

Other risk factors include lower socioeconomic status (poor hygiene and eating habits), atrophic gastritis, anxiety and stress, steroids, vitamin deficiency, Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, MEN syndrome, and hyperparathyroidism. Factors specific to gastric ulcers include gastric stasis, ischemia of gastric mucosa, and duodeno-gastric reflux.[4]

Epidemiology

The lifetime prevalence of peptic ulcer disease (PUD) is declining and is currently estimated to be between 5-10%. It tends to be less prevalent in developed countries. Just as there has been a downward trend in the overall incidence of peptic ulcer disease, so too has there been a decline in the overall rate of complications.[1] Even though the overall incidence of complications is declining, complications including bleeding, perforation, and obstruction are responsible for nearly 150,000 hospitalizations annually in the United States.[5] Upper GI bleeding is the most common complication of peptic ulcer disease. The next most common complication is perforation. The annual incidence of upper GI bleeding secondary to a peptic ulcer is estimated to be between 19 to 57 cases per 100,000 individuals. In comparison, ulcer perforation is expected to be 4 to 14 cases per 100,000 individuals. Advanced age is a risk factor as 60% of patients with PUD are older than 60. Infections with Helicobacter pylori and the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are each identified as risk factors for the development of bleeding ulcers and peptic ulcer perforation.[6]

Pathophysiology

The ulcerogenic process occurs as a result of damage to the protective mucosal lining of the stomach and duodenum. H.pylori infections and the use of NSAIDs and low-dose aspirin are known to damage the mucosal lining. The cost to the mucosal lining in the setting of an H.pylori infection is the result of both bacterial factors and the host's inflammatory response. In the case of NSAID (and aspirin) use, mucosal damage is secondary to inhibition of cyclooxygenase 1 (COX-1) derived prostaglandins which are important in maintaining mucosal integrity.[1] Once the mucosal layer is disrupted, the gastric epithelium is exposed to acid, and the ulcerative process ensues. If the process continues, the ulcer deepens reaching the serosal layer. A perforation occurs once the serosal layer is breached at which point the gastric contents are released into the abdominal cavity.[7]

Gastric ulcers are classified into four types based on location.[8]

- Type 1: in the antrum, near the lesser curvature

- Type 2: combined gastric and duodenal ulcer

- Type 3: Prepyloric ulcer

- Type 4: ulcer in the proximal stomach or cardia

Gastric ulcers are most commonly found in the lesser curvature (55%), followed by a combination of duodenal and gastric ulcers. Duodenal ulcers are most commonly located in the first part of the duodenum.

Gastric ulcers have malignant potential compared to duodenal ulcers that do not have cancerous risk. A gastric ulcer greater than 3 cm is called a giant gastric ulcer which has a 6%-23% chance to turn into malignancy. In previous literature, the cancer rate in endoscopically diagnosed gastric ulcers ranges from 2.4%–21%.[9][10]

Histopathology

Microscopically, a peptic ulcer consists of chronic inflammatory cells and granulation tissue, endarteritis obliterans, and epithelial proliferation. Peptic ulcers have four prototypical zones:

- Superficially located neutrophils, bacteria, and necrotic areas

- Fibrinoid necrosis at base of the ulcers and its margins

- Chronic inflammatory cells with accompanying granulation tissue

- Fibrous scars in the muscularis propria layer showing blood vessels with underlying endarteritis obliterans

History and Physical

Although approximately 70% of patients with peptic ulcer disease may initially be asymptomatic, most patients with a perforated peptic ulcer will present with symptoms. Special populations such as the extremes of age (young or elderly), immunocompromised, and those with altered level of consciousness may prove to be more challenging in obtaining a reliable history. When an honest account is obtainable, a detailed history may identify other symptoms that may have been present before ulcer perforation. The most common symptom in patients with peptic ulcer disease is dyspepsia or upper abdominal pain. This pain may be vague upper abdominal discomfort or it may be localized to either the right upper quadrant, left upper quadrant, or epigastrium. Gastric ulcers may be worsened by food whereas pain from a duodenal ulcer may be delayed 2-5 hours after eating. Patients who are experiencing bleeding from a peptic ulcer may complain of nausea, hematemesis, or melanotic stools. Some patients may report bright red blood per rectum or maroon-colored stool if the upper gi bleeding is brisk.

Patients with peptic ulcer perforation typically will complain of sudden and severe epigastric pain. Pain while initially localized, quickly becomes more generalized in location. Patients may present with symptoms of lightheadedness or syncope secondary to hypotension from blood loss or SIRS (systemic inflammatory response syndrome)/sepsis. After several hours, abdominal pain may temporarily improve though it is still reproducible by movement. If there is a delay in seeking medical attention and the perforation is not walled off, patients are likely to experience increasing abdominal distension along with clinical manifestations of SIRS/sepsis.[5][11]

A thorough physical examination should be done on all patients complaining of abdominal pain. Those with a perforated peptic ulcer are likely to have diffuse abdominal tenderness that progresses to guarding and rigidity. Rectal examination may demonstrate positive guaiac stools. Patients are likely to be tachycardic and may be hypotensive. They may be febrile and have mental status changes if there has been a delay in presentation.[5]

Evaluation

The evaluation of a patient in whom perforated peptic ulcer is suspected should be done quickly as the morbidity and mortality increase significantly with time. Even if a perforated peptic ulcer is suspected due to history and physical examination, diagnostic studies should be obtained to confirm the diagnosis and to rule out other possible etiologies. Typical workup includes labs and imaging studies. Standard labs should include complete blood count (CBC), chemistry panel, liver function tests, coagulation profile, and lipase levels (to rule out pancreatitis). Blood type and screening should be done as well. A set of blood cultures and lactic acid should be done on patients meeting the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria. Lactic acid will help elucidate coexistent ischemia. A urinalysis can be done in patients with similar pain or those with urinary symptoms.

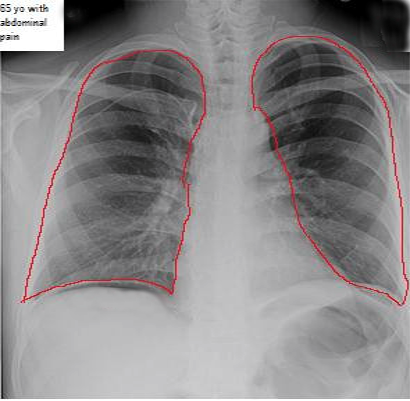

Imaging studies should be obtained once the patient is stabilized. While plain abdominal films or chest x-ray may demonstrate free air, a computed tomogram (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis will have the highest yield diagnostically. Intravenous (IV) or oral contrast is not required to illustrate pneumoperitoneum, but IV contrast may be used in patients with undifferentiated abdominal pain/peritonitis.

Treatment / Management

Perforated peptic ulcers are life-threatening conditions with a mortality rate that approaches 30%. Early surgery and aggressive management of sepsis are the mainstays of therapy.[7] An initial emergent surgery consultation is required in all patients with peritonitis even before definitive diagnosis. Patients should be resuscitated with crystalloids, antibiotics, and analgesics. Administration of early intravenous antibiotics should be considered, especially for patients presenting with SIRS criteria. Once the diagnosis of peptic ulcer perforation is made, a nasogastric tube should be placed, and IV proton pump inhibitor should be administered, IV antibiotics should be given, and a surgical evaluation must be done. Then the decision can be made regarding whether the patient will require surgery.

Sepsis accounts for approximately half of all mortalities in the setting of perforated peptic ulcers.[7] Given the high prevalence of sepsis and its associated mortality, antibiotics should be administered to all patients with a perforated peptic ulcer. Antibiotics should be broad-spectrum and cover gram-negative rods and anaerobes. A combination of a third-generation cephalosporin and metronidazole is a reasonable choice as is monotherapy with a combination beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitor (i.e., ampicillin-sulbactam, piperacillin-tazobactam).[12]

Intravenous proton pump inhibitors (PPI) help bleeding cessation and facilitate healing, but efficacy in perforated ulcers has not been established. That said, intravenous PPI administration should be given to creating a neutral pH environment that aids in maintaining platelet aggregation and hence should promote rapid sealing of perforated ulcers.[1][13]

The mainstay treatment for a perforated peptic ulcer is early operative intervention as mortality significantly increases with surgical delay.[14] Surgery will typically consist of a peritoneal lavage of 5-10 liters of saline followed by an interrupted sutured closure of the perforated ulcer followed by an omental patch (Roseo-Graham patch). A drain is placed in the dependent areas and the abdomen is closed. The surgical drain is removed on postoperative days 3-5. This procedure can be done by an open approach or laparoscopically as there have been no significant differences in terms of mortality or clinically significant outcomes when comparing the two methods. A select number of patients may be chosen to forego surgery in favor of medical treatment alone. This option is a decision that would be made by the surgical consultant and would be limited to patients less than 70 years old with early presentation (less than 24 hours), mild/localized symptoms, and in stable condition. In such patients, perforated peptic ulcer is managed by iv fluids, antibiotics, Ryle's tube aspiration, constant monitoring of urine output, and electrolytes. This is referred to as the Hermen-Taylor regimen.[7][13] After 12 weeks follow-up gastroscopy must be done.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis includes but is not limited to the following:

- Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA)

- Acute coronary syndrome

- Aortic dissection

- Appendicitis

- Boerhaave syndrome

- Cholecystitis

- Cholelithiasis

- Choledocholithiasis

- Diverticulitis

- Duodenitis

- Esophagitis

- Foreign body ingestion

- Gastritis

- Hepatitis

- Hernia

- Mesenteric ischemia

- Neoplasm

- Nephrolithiasis

- Pyelonephritis

- Small bowel obstruction

- Ureterolithiasis

- Volvulus

Surgical Oncology

Gastric ulcers are premalignant and hence biopsy of the ulcer or perforation margins are indicated in such patients. If found positive for neoplasia, thorough staging using endoscopy and imaging is used to stage and grade the disease, followed by resection or a combination of chemotherapy and surgery is recommended.

Prognosis

The mortality rate of perforated peptic ulcer is ten times higher than that seen with acute appendicitis or cholecystitis. Though bleeding is a more common complication than perforation (6:1), the mortality rate is 5-fold higher with a perforated peptic ulcer compared with a bleeding peptic ulcer.[7] The estimated 30-day mortality rate with perforation is 24%.[6] Patients with comorbidities or those older than 65 have a worse prognosis. Similarly, patients who have a delayed presentation or have a shock on initial presentation also have increased mortality.[6]

Complications

Complications of untreated peptic ulcer perforation are severe and will eventually lead to patient demise. Short-term complications include:

- Hypovolemia

- Shock

- Sepsis

- Gastrocolic fistula formation

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients with peptic ulcer disease should be warned about the possible complication of perforation. They should be counseled on medication compliance to ensure adequate healing of the ulcer occurs. Smoking cessation should be emphasized and other aggravating agents should be avoided as much as possible. These include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), alcohol, and caffeinated beverages.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Managing a patient with a perforated peptic ulcer can be challenging given the morbidity and mortality associated with the disease. Hence it requires an interprofessional approach to maximize the chances of a favorable outcome. Diagnosis relies on suspicion of the underlying disorder. This treatment begins with the nurse triaging the patient and continues with the emergency medicine provider. Once suspected, resuscitative measures must be initiated while diagnostic studies are being obtained. This takes a coordinated effort between the ED provider and staff members of the nursing, pharmacy, and radiology departments. Once the diagnosis is made, further communication is required between the ED provider and the on-call surgeon. Interprofessional communication is central to an expedited workup and treatment with the ultimate goal of getting the appropriate patient to the operating room promptly as the surgical delay has been related to mortality.