Continuing Education Activity

Acute cholecystitis is inflammation of the gallbladder that occurs due to occlusion of the cystic duct or impaired emptying of the gallbladder. Often this impaired emptying is due to stones or biliary sludge. This activity reviews the evaluation and management of acute cholecystitis and reviews the role of the interprofessional team in caring for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

Identify the risk factors for acute cholecystitis.

Describe the classic presentation for a patient with acute cholecystitis.

Explain the management of acute cholecystitis.

Explain how to improve patient outcomes by employing a well-integrated team approach to the management of patients with acute cholecystitis.

Introduction

Acute cholecystitis refers to inflammation of the gallbladder. The pathophysiologic mechanism of acute cholecystitis is blockage of the cystic duct. Cholecystitis is a condition best treated with surgery; however, it can be treated conservatively if necessary. This condition can be associated with or without the presence of gallstones and can also be classified as acute or chronic. It is found both in men and women but may have a propensity for certain populations. It may also present with certain classic signs and symptoms. Acute cholecystitis may also be confused with other illnesses such as peptic ulcer disease, irritable bowel disease, and cardiac disease. Chronic and acute pancreatitis can also mimic gallbladder disease.[1][2][3]

Etiology

The etiology of acute cholecystitis is, by definition, cystic duct blockage, which causes inflammation. Normally, bile is made in the liver and travels down the bile duct, and is stored in the gallbladder. After eating certain foods, especially spicy or greasy foods, the gallbladder is stimulated to empty the bile of the gallbladder, through the cystic duct, down the bile duct into the duodenum. This process aids in food digestion.

The gallbladder not only stores the bile, but it also can concentrate it. Concentrated bile is susceptible to precipitation forming stones when homeostasis is disrupted, which can occur due to bile stasis, supersaturation from the liver of cholesterol and lipids, disruption in the concentration process, and cholesterol crystal nucleation.

When cystic duct blockage is caused by a stone, it is called acute calculous cholecystitis. It is important to know, one can have pain due to temporary obstruction by gallstones, and that is called biliary colic. The diagnosis of biliary colic is upgraded to acute calculous cholecystitis if the pain does not resolve in six hours. If no stone is identified, it is called acute acalculous cholecystitis.[4][5]

Regardless of the cause of the blockage, the gallbladder wall edema will eventually cause wall ischemia and become gangrenous. The gangrenous gallbladder can become infected by gas-forming organisms, causing acute emphysematous cholecystitis; all of these conditions can quickly become life-threatening, and rupture has a high rate of mortality.

About 95% of people with acute cholecystitis have gallstones. [6] However that does not mean incidental findings of gallstone should be treated, as it is estimated that only 20% of patients with asymptomatic stones will develop symptoms within 20 years[7], and because approximately 1% of patients with asymptomatic stones develop complications of their stones before the onset of symptoms, prophylactic cholecystectomy is not warranted in asymptomatic patients.

Epidemiology

Gallbladder disease occurs in men and women, with certain populations being more prone to it. The risk of gallbladder disease increases in women, obese patients, pregnant women, and patients in their 40s. Drastic weight loss or acute illnesses may also increase the risk. The formation of gallstones and this condition can run in families. Other conditions that cause the breakdown of blood cells, for example, sickle cell disease, also increase the incidence of gallstones.

Pathophysiology

Occlusion of the cystic duct or malfunction of the mechanics of gallbladder emptying is the pathophysiology of this disease. Cases of acute untreated cholecystitis could lead to perforation of the gallbladder, sepsis, and death. Gallstones form from various materials such as bilirubinate or cholesterol. These materials increase the likelihood of cholecystitis and cholelithiasis in conditions such as sickle cell disease where red blood cells are broken down forming excess bilirubin and forming pigmented stones. Patients with excessive calcium such as in hyperparathyroidism can form calcium stones. Patients with excessive cholesterol can form cholesterol stones. Occlusion of the common bile duct such as in neoplasms or strictures can also lead to stasis of the bile flow causing gallstone formation.[8][9]

Histopathology

During the early phase, the gallbladder will usually reveal extensive venous congestion and edema. With time, fibrosis and the presence of chronic inflammatory cells may appear. More advanced cases may present with perforation or gangrene.

History and Physical

Cases of chronic cholecystitis present with progressing right upper quadrant abdominal pain with bloating, food intolerances (especially greasy and spicy foods), increased gas, nausea, and vomiting. Pain in the midback or shoulder may also occur. This pain could be present for years until diagnosis. Cases of acute cholecystitis have similar symptoms only more severe. Often symptoms are mistaken for cardiac issues. The finding of right upper abdominal pain with deep palpation, Murphy sign, is usually classic for this disease. Often, there is a specific dietary event leading to the acute attack, e.g., "I ate pork chops and gravy last night."

Evaluation

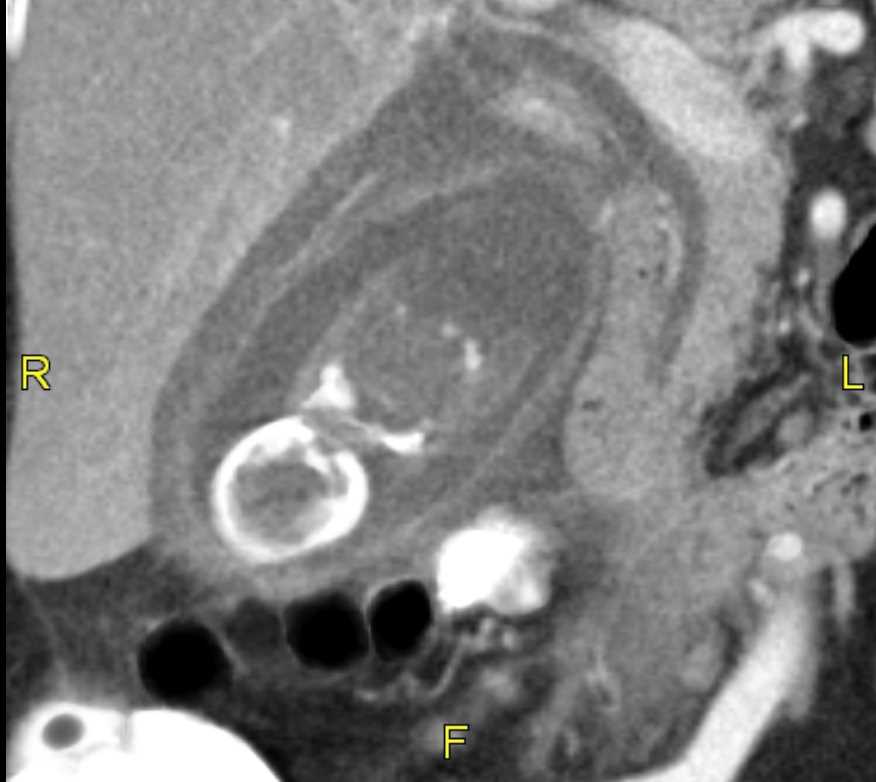

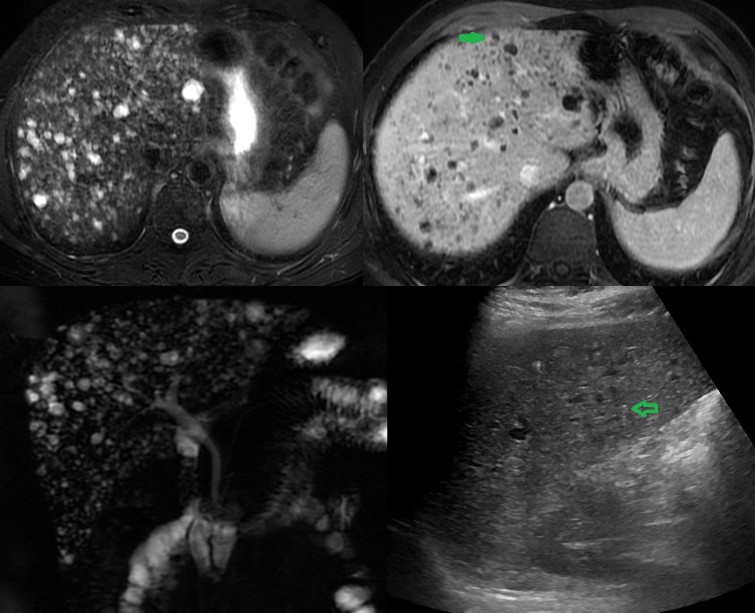

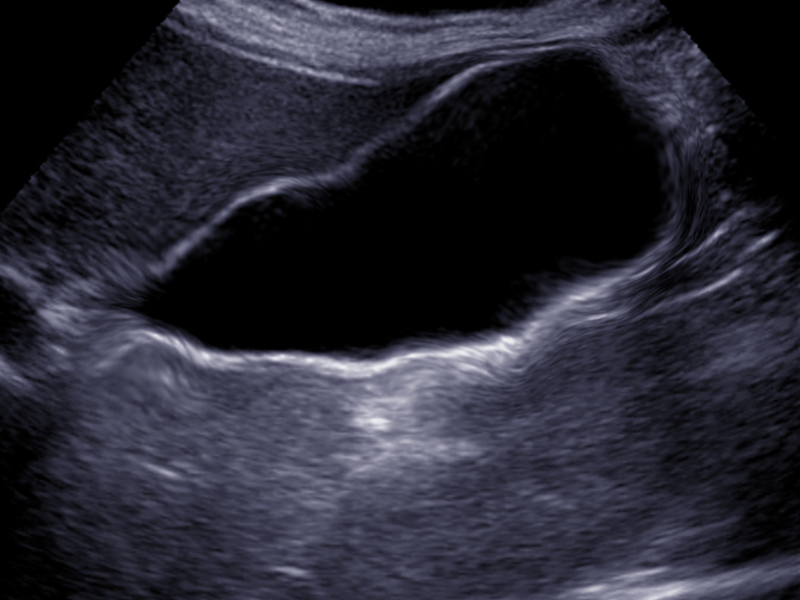

A physical exam with a comprehensive history is paramount in making the diagnosis of cholecystitis. A complete blood count (CBC) and a comprehensive metabolic panel are also important. In cases of chronic cholecystitis, these results may be normal. In acute cholecystitis or severe disease, white blood cell count (WBC) may be elevated. Liver enzymes may also be elevated. If there is a high bilirubin level above 2, then consider a possible common bile duct stone. Note that even in the presence of severe gallbladder disease, lab values may be normal. Amylase and lipase must also be checked to rule out pancreatitis. Often a CT scan is ordered in the emergency department as the first imaging test in the workup. Findings of cholecystitis and gallstones can often be seen in this imaging. A gallbladder ultrasound is the best test to evaluate gallbladder disease initially. A thickened gallbladder wall and gallstones are common findings with this condition. In cases of acute cholecystitis, a hepatobiliary (HIDA) scan is recommended. This scan will diagnose gallbladder function or cystic duct obstruction. The addition of cholecystokinin (CCK) in cases of no gallstones may also diagnose acalculous cholecystitis. This is indicated by an ejection fracture of less than 35%.[10][11]

Treatment / Management

The most appropriate management of cholecystitis is laparoscopic cholecystectomy. There are low morbidity and mortality rates with quick recovery. This can also be done with an open technique in cases where the patient is not a good laparoscopic candidate. In situations in which the patient is acutely ill and considered a poor surgical candidate, he or she may be treated with temporizing percutaneous drainage of the gallbladder. Milder cases of chronic cholecystitis in patients considered poor surgical candidates might be managed with low-fat and low-spice diets. The results of this treatment vary. Medical treatment of gallstones with ursodiol also has been reported to have occasional success.[12][13][3]

Differential Diagnosis

- Appendicitis

- Biliary colic

- Cholangitis

- Mesenteric ischemia

- Gastritis

- Peptic ulcer disease

Complications

The complications of acute cholecystitis include:

- Biloma

- Intraabdominal abscess

- Bile duct injury

- Hepatic injury

- Small bowel injury

- Infection

- Retained stones in the bile duct

- Bleeding

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Once the gallbladder has been removed, most patients can be discharged on the same day.

The pain is minimal and can be managed by over-the-counter analgesics. The patient may complain of severe shoulder pain due to retained CO2 from laparoscopic insufflation and should be explained that such pain will dissipate as the patient moves and gas is slowly absorbed, which can take up to three days.

Prior to discharge, the patient should be advised on possible intolerance to greasy food, which may cause bloating or diarrhea. This can be temporary or, at some degree permanent, due to the decreased speed of fat emulsification by the loss of stored bile in the gallbladder. Most patients will have an up-regulation in bile production by the liver and will see improvement in symptoms with time.

Follow-up time is between 3-4 weeks from operation.

Pearls and Other Issues

Cholecystitis can occur in the very young and very old, but the highest incidence is in the fourth decade. The classic mantra of "fat, forty, fertile, and flatulent" often applies. Food intolerances are usually the initiating factor of nausea, vomiting, and bloating, but as this condition progresses, there may be persistent symptoms even when the patient has not eaten. The preferred recommended treatment is the removal of the gallbladder. In the past, this was done through an open laparotomy incision. Now laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the procedure of choice. This procedure has low mortality and morbidity, a quick recovery time (usually one week), and good results. At times, patients present to the primary care practitioner with mild symptoms of cholecystitis and gallstones. This can present a challenge to the physician to know what is the appropriate treatment. Often conservative medical management is recommended. This would include low-fat diet modification and possible weight loss. Unfortunately, for surgeons, these patients often present to the emergency department with symptoms of acute cholecystitis and undergo urgent surgery. This situation also increases operative morbidity rates. Therefore, general surgeons usually recommend patients undergo elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy earlier than later in the course of the disease. Other considerations would be the passing of gallstones into the bile duct causing biliary obstruction and possible pancreatitis.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Managing acute cholecystitis is now routine, and most patients have an excellent prognosis. However, problems arise in patients with acalculous cholecystitis and when there are bile duct stones. Patients with acalculous cholecystitis are often managed in the intensive care unit and may undergo an initial aspiration procedure until they are fit to undergo formal surgery. Since many of these patients have high comorbidity, monitoring them is critical. Educating the patient and family is vital since the condition does carry a high mortality. The other group of patients who may have a prolonged stay are those with a bile duct stone. These patients require an ERCP prior to cholecystectomy. Again ERCP is not a benign procedure, and patients need to be educated about the procedure and potential complications.

Patients with numerous comorbid factors need to be evaluated by the cardiologist prior to general anesthesia. The preoperative nurse should ensure that the patient has the requisite clearance, ECG, chest x-ray, and blood work before the surgery. If there are any deficiencies or concerns, the surgeon should be contacted prior to the procedure.[14][15][16] (Level V) After the procedure, the nurse will monitor vital signs and assist in managing the patient's pain. If there is any significant change in vital signs or the pain cannot be controlled with the medications provided, the surgeon should be consulted. Pre-operatively, the pharmacist should access the patient's medications and make sure that there is no concern for withdrawal or potential interaction with the anesthetics. The clinical team should be apprised if there are any concerns.

Outcomes

For patients with uncomplicated acute cholecystitis, the prognosis is excellent. The mortality rates are very low. Perforation or gangrene of the gallbladder may occur in delayed cases. Patients with acalculous cholecystitis have high mortality varying from 20-50%.

In severe cases of acute cholecystitis, the intense inflammation can make surgery difficult, resulting in injury to the bile duct, which has substantial morbidity.[17][18] [Level 5]