[1]

MacPherson P, Lebina L, Motsomi K, Bosch Z, Milovanovic M, Ratsela A, Lala S, Variava E, Golub JE, Webb EL, Martinson NA. Prevalence and risk factors for latent tuberculosis infection among household contacts of index cases in two South African provinces: Analysis of baseline data from a cluster-randomised trial. PloS one. 2020:15(3):e0230376. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0230376. Epub 2020 Mar 17

[PubMed PMID: 32182274]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[2]

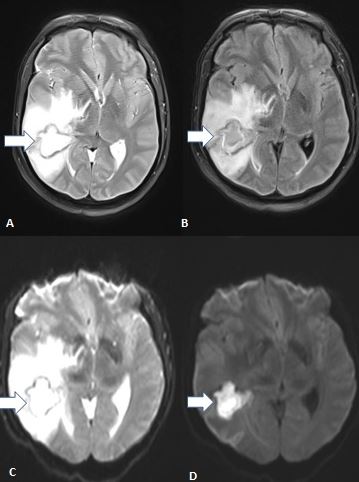

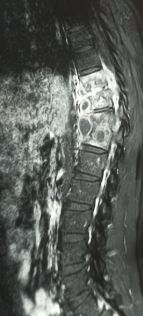

Schaller MA, Wicke F, Foerch C, Weidauer S. Central Nervous System Tuberculosis : Etiology, Clinical Manifestations and Neuroradiological Features. Clinical neuroradiology. 2019 Mar:29(1):3-18. doi: 10.1007/s00062-018-0726-9. Epub 2018 Sep 17

[PubMed PMID: 30225516]

[3]

Morton B, Stolbrink M, Kagima W, Rylance J, Mortimer K. The Early Recognition and Management of Sepsis in Sub-Saharan African Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2018 Sep 15:15(9):. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15092017. Epub 2018 Sep 15

[PubMed PMID: 30223556]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[4]

Herce ME, Muyoyeta M, Topp SM, Henostroza G, Reid SE. Coordinating the prevention, treatment, and care continuum for HIV-associated tuberculosis in prisons: a health systems strengthening approach. Current opinion in HIV and AIDS. 2018 Nov:13(6):492-500. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000505. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 30222608]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[5]

Romha G, Gebru G, Asefa A, Mamo G. Epidemiology of Mycobacterium bovis and Mycobacterium tuberculosis in animals: Transmission dynamics and control challenges of zoonotic TB in Ethiopia. Preventive veterinary medicine. 2018 Oct 1:158():1-17. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2018.06.012. Epub 2018 Jun 28

[PubMed PMID: 30220382]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[6]

Hayward S, Harding RM, McShane H, Tanner R. Factors influencing the higher incidence of tuberculosis among migrants and ethnic minorities in the UK. F1000Research. 2018:7():461. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.14476.2. Epub 2018 Apr 13

[PubMed PMID: 30210785]

[7]

Jamison DT, Gelband H, Horton S, Jha P, Laxminarayan R, Mock CN, Nugent R, Ogbuoji O, Qi J, Olson ZD, Yamey G, Nugent R, Norheim OF, Verguet S, Jamison DT. Annual Rates of Decline in Child, Maternal, Tuberculosis, and Noncommunicable Disease Mortality across 109 Low- and Middle-Income Countries from 1990 to 2015. Disease Control Priorities: Improving Health and Reducing Poverty. 2017 Nov 27:():

[PubMed PMID: 30212157]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[8]

Haddad MB, Raz KM, Lash TL, Hill AN, Kammerer JS, Winston CA, Castro KG, Gandhi NR, Navin TR. Simple Estimates for Local Prevalence of Latent Tuberculosis Infection, United States, 2011-2015. Emerging infectious diseases. 2018 Oct:24(10):1930-1933. doi: 10.3201/eid2410.180716. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 30226174]

[9]

Daftary A, Mitchell EMH, Reid MJA, Fekadu E, Goosby E. To End TB, First-Ever High-Level Meeting on Tuberculosis Must Address Stigma. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 2018 Nov:99(5):1114-1116. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.18-0591. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 30226149]

[10]

Migliori GB, Sotgiu G, Rosales-Klintz S, van der Werf MJ. European Union standard for tuberculosis care on treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis following new World Health Organization recommendations. The European respiratory journal. 2018 Nov:52(5):. pii: 1801617. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01617-2018. Epub 2018 Nov 8

[PubMed PMID: 30209200]

[12]

Habib S, Rajdev K, Pervaiz S, Hasan Siddiqui A, Azam M, Chalhoub M. Pulmonary Cavitary Disease Secondary to Mycobacterium xenopi Complicated by Respiratory Failure. Cureus. 2018 Oct 29:10(10):e3512. doi: 10.7759/cureus.3512. Epub 2018 Oct 29

[PubMed PMID: 30648049]

[13]

Narasimhan P, Wood J, Macintyre CR, Mathai D. Risk factors for tuberculosis. Pulmonary medicine. 2013:2013():828939. doi: 10.1155/2013/828939. Epub 2013 Feb 12

[PubMed PMID: 23476764]

[14]

Roy Chowdhury R, Vallania F, Yang Q, Lopez Angel CJ, Darboe F, Penn-Nicholson A, Rozot V, Nemes E, Malherbe ST, Ronacher K, Walzl G, Hanekom W, Davis MM, Winter J, Chen X, Scriba TJ, Khatri P, Chien YH. A multi-cohort study of the immune factors associated with M. tuberculosis infection outcomes. Nature. 2018 Aug:560(7720):644-648. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0439-x. Epub 2018 Aug 22

[PubMed PMID: 30135583]

[15]

Githinji LN, Gray DM, Zar HJ. Lung function in HIV-infected children and adolescents. Pneumonia (Nathan Qld.). 2018:10():6. doi: 10.1186/s41479-018-0050-9. Epub 2018 Jun 25

[PubMed PMID: 29984134]

[16]

Young DB, Gideon HP, Wilkinson RJ. Eliminating latent tuberculosis. Trends in microbiology. 2009 May:17(5):183-8. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2009.02.005. Epub 2009 Apr 16

[PubMed PMID: 19375916]

[17]

Santos NCS, Scodro RBL, Leal DC, do Prado SM, Micheletti DF, Sampiron EG, Costacurta GF, de Almeida AL, da Silva LA, Ieque AL, Ghiraldi Lopes LD, de Pádua RA, Siqueira VL, Caleffi-Ferracioli KR, Cardoso RF. Determination of minimum bactericidal concentration, in single or combination drugs, against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Future microbiology. 2020 Jan:15():107-114. doi: 10.2217/fmb-2019-0050. Epub 2020 Feb 17

[PubMed PMID: 32064924]

[18]

Nigsch A, Glawischnig W, Bagó Z, Greber N. Mycobacterium caprae Infection of Red Deer in Western Austria-Optimized Use of Pathology Data to Infer Infection Dynamics. Frontiers in veterinary science. 2018:5():350. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2018.00350. Epub 2019 Jan 21

[PubMed PMID: 30719435]

[19]

Barr DA, Lewis JM, Feasey N, Schutz C, Kerkhoff AD, Jacob ST, Andrews B, Kelly P, Lakhi S, Muchemwa L, Bacha HA, Hadad DJ, Bedell R, van Lettow M, Zachariah R, Crump JA, Alland D, Corbett EL, Gopinath K, Singh S, Griesel R, Maartens G, Mendelson M, Ward AM, Parry CM, Talbot EA, Munseri P, Dorman SE, Martinson N, Shah M, Cain K, Heilig CM, Varma JK, von Gottberg A, Sacks L, Wilson D, Squire SB, Lalloo DG, Davies G, Meintjes G. Mycobacterium tuberculosis bloodstream infection prevalence, diagnosis, and mortality risk in seriously ill adults with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data. The Lancet. Infectious diseases. 2020 Jun:20(6):742-752. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30695-4. Epub 2020 Mar 13

[PubMed PMID: 32178764]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[20]

Caws M, Thwaites G, Dunstan S, Hawn TR, Lan NT, Thuong NT, Stepniewska K, Huyen MN, Bang ND, Loc TH, Gagneux S, van Soolingen D, Kremer K, van der Sande M, Small P, Anh PT, Chinh NT, Quy HT, Duyen NT, Tho DQ, Hieu NT, Torok E, Hien TT, Dung NH, Nhu NT, Duy PM, van Vinh Chau N, Farrar J. The influence of host and bacterial genotype on the development of disseminated disease with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS pathogens. 2008 Mar 28:4(3):e1000034. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000034. Epub 2008 Mar 28

[PubMed PMID: 18369480]

[21]

Barnes PF, Bloch AB, Davidson PT, Snider DE Jr. Tuberculosis in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. The New England journal of medicine. 1991 Jun 6:324(23):1644-50

[PubMed PMID: 2030721]

[22]

Jones BE, Young SM, Antoniskis D, Davidson PT, Kramer F, Barnes PF. Relationship of the manifestations of tuberculosis to CD4 cell counts in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. The American review of respiratory disease. 1993 Nov:148(5):1292-7

[PubMed PMID: 7902049]

[23]

Nelson SM, Deike MA, Cartwright CP. Value of examining multiple sputum specimens in the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis. Journal of clinical microbiology. 1998 Feb:36(2):467-9

[PubMed PMID: 9466760]

[24]

Mase SR, Ramsay A, Ng V, Henry M, Hopewell PC, Cunningham J, Urbanczik R, Perkins MD, Aziz MA, Pai M. Yield of serial sputum specimen examinations in the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis: a systematic review. The international journal of tuberculosis and lung disease : the official journal of the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2007 May:11(5):485-95

[PubMed PMID: 17439669]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[25]

Steingart KR, Ng V, Henry M, Hopewell PC, Ramsay A, Cunningham J, Urbanczik R, Perkins MD, Aziz MA, Pai M. Sputum processing methods to improve the sensitivity of smear microscopy for tuberculosis: a systematic review. The Lancet. Infectious diseases. 2006 Oct:6(10):664-74

[PubMed PMID: 17008175]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[26]

Lewinsohn DM, Leonard MK, LoBue PA, Cohn DL, Daley CL, Desmond E, Keane J, Lewinsohn DA, Loeffler AM, Mazurek GH, O'Brien RJ, Pai M, Richeldi L, Salfinger M, Shinnick TM, Sterling TR, Warshauer DM, Woods GL. Official American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Clinical Practice Guidelines: Diagnosis of Tuberculosis in Adults and Children. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2017 Jan 15:64(2):e1-e33. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw694. Epub 2016 Dec 8

[PubMed PMID: 27932390]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[27]

Chihota VN, Grant AD, Fielding K, Ndibongo B, van Zyl A, Muirhead D, Churchyard GJ. Liquid vs. solid culture for tuberculosis: performance and cost in a resource-constrained setting. The international journal of tuberculosis and lung disease : the official journal of the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2010 Aug:14(8):1024-31

[PubMed PMID: 20626948]

[28]

O'Grady J, Maeurer M, Mwaba P, Kapata N, Bates M, Hoelscher M, Zumla A. New and improved diagnostics for detection of drug-resistant pulmonary tuberculosis. Current opinion in pulmonary medicine. 2011 May:17(3):134-41. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e3283452346. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 21415753]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[29]

Bergot E, Abiteboul D, Andréjak C, Antoun F, Barras E, Blanc FX, Bourgarit A, Charlois-Ou C, Delacourt C, Dirou S, Gerin M, Guerin S, Haustraete É, Henry B, Lucet JC, Maitre T, Morin J, Le Palud P, Pommelet V, Rivoisy C, Robert J, Veziris N, Herrmann JL. [Practice recommendations for the use and interpretation of interferon gamma release assays in the diagnosis of latent and active tuberculosis]. Revue des maladies respiratoires. 2018 Oct:35(8):852-858. doi: 10.1016/j.rmr.2018.08.007. Epub 2018 Sep 14

[PubMed PMID: 30224215]

[30]

Blanc FX, Dirou S, Morin J, Veziris N. [Interferon gamma release assay tests for the diagnosis of active tuberculosis]. Revue des maladies respiratoires. 2018 Oct:35(8):894-899. doi: 10.1016/j.rmr.2018.08.016. Epub 2018 Sep 13

[PubMed PMID: 30220491]

[31]

Holmes KK, Bertozzi S, Bloom BR, Jha P, Bloom BR, Atun R, Cohen T, Dye C, Fraser H, Gomez GB, Knight G, Murray M, Nardell E, Rubin E, Salomon J, Vassall A, Volchenkov G, White R, Wilson D, Yadav P. Tuberculosis. Major Infectious Diseases. 2017 Nov 3:():

[PubMed PMID: 30212088]

[32]

Lewinsohn DM, Leonard MK, LoBue PA, Cohn DL, Daley CL, Desmond E, Keane J, Lewinsohn DA, Loeffler AM, Mazurek GH, O'Brien RJ, Pai M, Richeldi L, Salfinger M, Shinnick TM, Sterling TR, Warshauer DM, Woods GL. Official American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Clinical Practice Guidelines: Diagnosis of Tuberculosis in Adults and Children. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2017 Jan 15:64(2):111-115. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw778. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 28052967]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[33]

John M, Chhikara A, John DM, Khawar N, Brown B, Narula P. Diagnosis of Tuberculosis in an Asymptomatic Child, Sibling, and Symptomatic Pregnant Mother in New York City by Tuberculin Skin Testing and the Importance of Screening High-Risk Urban Populations for Tuberculosis. The American journal of case reports. 2018 Aug 24:19():1004-1009. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.909148. Epub 2018 Aug 24

[PubMed PMID: 30139931]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[34]

Cavany SM, Vynnycky E, Anderson CS, Maguire H, Sandmann F, Thomas HL, White RG, Sumner T. Should NICE reconsider the 2016 UK guidelines on TB contact tracing? A cost-effectiveness analysis of contact investigations in London. Thorax. 2019 Feb:74(2):185-193. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-211662. Epub 2018 Aug 18

[PubMed PMID: 30121574]

[35]

T C, L N, Vo N, L N, Tg T, Fc O. PROPOSED GUIDELINES TO MINIMISE MULTI-DRUG RESISTANT TUBERCULOSIS TREATMENT DEFAULT IN A MULTI-DRUG RESISTANT UNIT OF LIMPOPO PROVINCE, SOUTH AFRICA. African journal of infectious diseases. 2018:12(2):55-65. doi: 10.21010/ajid.v12i2.9. Epub 2018 Jun 18

[PubMed PMID: 30109287]

[36]

Garfein RS, Liu L, Cuevas-Mota J, Collins K, Muñoz F, Catanzaro DG, Moser K, Higashi J, Al-Samarrai T, Kriner P, Vaishampayan J, Cepeda J, Bulterys MA, Martin NK, Rios P, Raab F. Tuberculosis Treatment Monitoring by Video Directly Observed Therapy in 5 Health Districts, California, USA. Emerging infectious diseases. 2018 Oct:24(10):1806-1815. doi: 10.3201/eid2410.180459. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 30226154]

[37]

Kibuule D, Verbeeck RK, Nunurai R, Mavhunga F, Ene E, Godman B, Rennie TW. Predictors of tuberculosis treatment success under the DOTS program in Namibia. Expert review of respiratory medicine. 2018 Nov:12(11):979-987. doi: 10.1080/17476348.2018.1520637. Epub 2018 Oct 4

[PubMed PMID: 30198358]

[38]

Muruganandah V, Sathkumara HD, Pai S, Rush CM, Brosch R, Waardenberg AJ, Kupz A. A systematic approach to simultaneously evaluate safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy of novel tuberculosis vaccination strategies. Science advances. 2020 Mar:6(10):eaaz1767. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaz1767. Epub 2020 Mar 4

[PubMed PMID: 32181361]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[39]

Moule MG, Cirillo JD. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Dissemination Plays a Critical Role in Pathogenesis. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology. 2020:10():65. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00065. Epub 2020 Feb 25

[PubMed PMID: 32161724]

[40]

Thakur AK, Chellappan DK, Dua K, Mehta M, Satija S, Singh I. Patented therapeutic drug delivery strategies for targeting pulmonary diseases. Expert opinion on therapeutic patents. 2020 May:30(5):375-387. doi: 10.1080/13543776.2020.1741547. Epub 2020 Mar 21

[PubMed PMID: 32178542]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[41]

Cocozza AM, Linh NN, Nathavitharana RR, Ahmad U, Jaramillo E, Gargioni GEM, Fox GJ. An assessment of current tuberculosis patient care and support policies in high-burden countries. The international journal of tuberculosis and lung disease : the official journal of the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2020 Jan 1:24(1):36-42. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.19.0183. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 32005305]

[42]

Conradie F, Diacon AH, Ngubane N, Howell P, Everitt D, Crook AM, Mendel CM, Egizi E, Moreira J, Timm J, McHugh TD, Wills GH, Bateson A, Hunt R, Van Niekerk C, Li M, Olugbosi M, Spigelman M, Nix-TB Trial Team. Treatment of Highly Drug-Resistant Pulmonary Tuberculosis. The New England journal of medicine. 2020 Mar 5:382(10):893-902. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1901814. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 32130813]

[43]

Hirsch-Moverman Y, Howard AA, Frederix K, Lebelo L, Hesseling A, Nachman S, Mantell JE, Lekhela T, Maama LB, El-Sadr WM. The PREVENT study to evaluate the effectiveness and acceptability of a community-based intervention to prevent childhood tuberculosis in Lesotho: study protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2017 Nov 21:18(1):552. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-2184-0. Epub 2017 Nov 21

[PubMed PMID: 29157275]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[44]

van Rensburg AJ, Engelbrecht M, Kigozi G, van Rensburg D. Tuberculosis prevention knowledge, attitudes, and practices of primary health care nurses. International journal of nursing practice. 2018 Dec:24(6):e12681. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12681. Epub 2018 Jul 31

[PubMed PMID: 30066350]

[45]

Tang ZQ, Jiang RH, Xu HB. Effectiveness of pharmaceutical care on treatment outcomes for patients with first-time pulmonary tuberculosis in China. Journal of clinical pharmacy and therapeutics. 2018 Dec:43(6):888-894. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.12746. Epub 2018 Jul 12

[PubMed PMID: 30003561]

[46]

Muthu V, Agarwal R, Dhooria S, Aggarwal AN, Behera D, Sehgal IS. Outcome of Critically Ill Subjects With Tuberculosis: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Respiratory care. 2018 Dec:63(12):1541-1554. doi: 10.4187/respcare.06190. Epub 2018 Sep 11

[PubMed PMID: 30206126]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence