Introduction

The kidneys are bean-shaped organs, with medial concavity and lateral convexity, weighing anywhere from 150 to 200 g in males and about 120 to 135 g in females. The dimensions are usually a length of 10 to 12 cm, a width of 5 to 7 cm, and a thickness of 3 to 5 cm. Each kidney is about the size of a closed fist. They are located retroperitoneally on the posterior abdominal wall and are found between the transverse processes of T12 and L3. Both of the upper poles are usually oriented slightly medially and posteriorly relative to the lower poles. If the upper renal poles are oriented laterally, this could suggest a horseshoe kidney or a superior pole renal mass. Further, the right kidney is usually slightly more inferior in position than the left kidney, likely because of the liver.[1]

The following are the kidneys relative to surrounding organs:[2][3][4]

- Superiorly, on top of each kidney and separated by renal fascia, are the suprarenal glands (adrenal glands), the right pyramidal suprarenal gland oriented apically on the right kidney and the left crescentic suprarenal gland oriented more medially on the left kidney

- The right kidney is posterior to the ascending colon, the second part of the duodenum medially, and the liver, separated by the hepatorenal recess

- The left kidney is posterior to the descending colon, its renal hilum lateral to the tail of the pancreas, superomedial aspect adjacent to the greater curvature of the stomach, and left upper pole adjacent to the spleen and connected by splenorenal ligaments

Posteriorly, the diaphragm rests over the upper third of each kidney with the 12th rib passing posteriorly over the upper pole. The kidneys usually sit located over the medial aspect of the psoas muscle and the lateral aspect of the quadratus lumborum. The proximal ureters will typically pass over the psoas muscle on their way to the bony pelvis.[2]

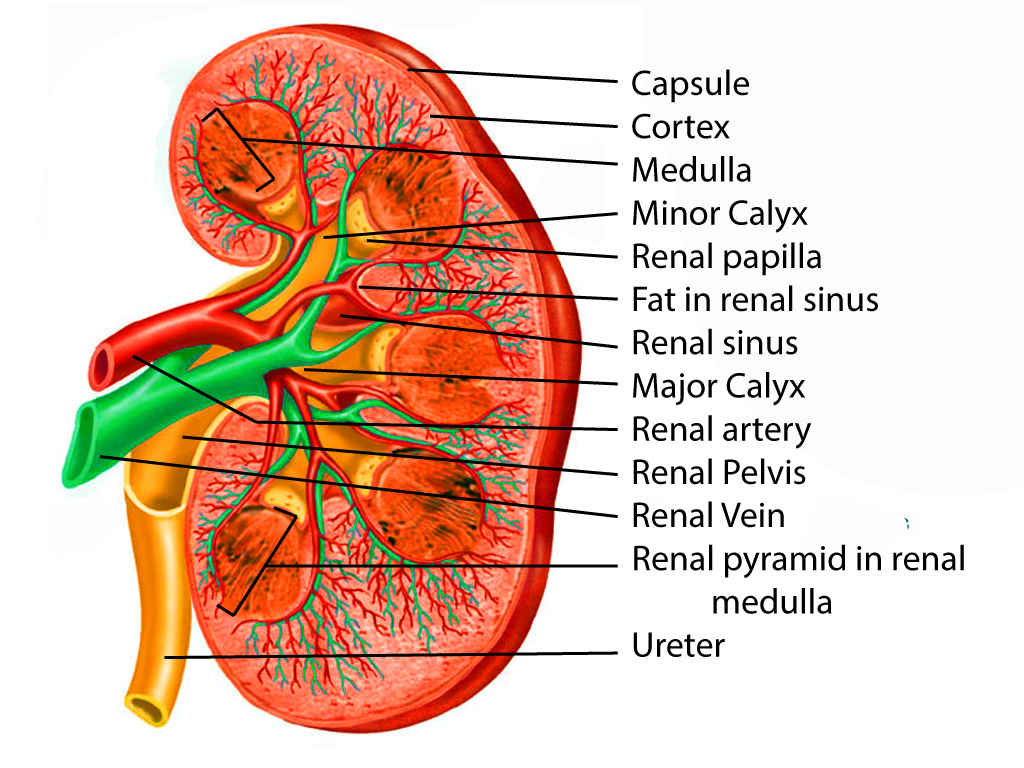

At the medial margin of each kidney lies the renal hilum, where the renal artery enters, and the renal pelvis and vein leave the renal sinus. The renal vein is found anterior to the renal artery, which is anterior to the renal pelvis. The renal pelvis is the flattened, superior end of the ureter. It receives 2 or 3 major calyces, each of which receives 2 or 3 minor calyces. The minor calyces are indented by the renal papillae, which are the apices of the renal pyramids. A pyramid and its cortical tissue comprise a lobe.[5]

Each kidney is covered by a two-layered capsule and is surrounded by perinephric fat, Gerota's fascia, Zuckerkandl fascia, and paranephric fat. The entire area immediately involving the kidneys is considered the retroperitoneum.[3][2]

Structure and Function

The kidney is composed of two regions: the cortex and medulla. The cortex is composed of renal corpuscles, convoluted tubules, straight tubules, collecting tubules, collecting ducts, and vasculature. Medullary rays, comprised of straight tubules and collecting ducts, extend into the cortex from the medulla. The medulla also contains the vasa recta, a network of capillaries integral to the countercurrent exchange system. Pyramids are conical structures formed by the collecting of tubules in the medulla, oriented with the base towards the cortex and apices towards the hilum. The papillae at the apices of the pyramids extend into minor calyces and drain via the collecting ducts at their tips, the area cribrosa. A collecting duct and the group of nephrons that it drains is referred to as a lobule.[6]

Nephrons are the functional units of the kidney. There are approximately 2 million nephrons per adult kidney. An afferent arteriole supplies a network of capillary loops termed the glomerulus, which is surrounded by a double-layered epithelium, Bowman's capsule, to collectively form a renal corpuscle. An efferent arteriole drains the glomerulus and becomes the vasa recta that supplies the renal tubules. Distal to Bowman's capsule is sequentially: the proximal convoluted tubule, proximal straight tubule or thick descending limb of the loop of Henle, thin descending limb of the loop of Henle, thin ascending limb of the loop of Henle, distal straight tubule or think ascending limb of the loop of Henle, distal convoluted tubule, collecting tubule, cortical collecting duct, medullary collecting duct, papillary duct, minor calyx, major calyx, renal pelvis, and ureter. The tubules begin in the cortex, descend into the medulla, make a hairpin turn in the thin limb of the loop of Henle, and ascend toward the cortex near its original renal corpuscle.[7][8]

The glomerular filtration barrier of the renal corpuscle is composed of fenestrated endothelium of glomerular capillaries, glomerular basement membrane (GBM), and visceral layer of Bowman's capsule containing podocytes that extend around the capillaries. Foot processes extending from the podocytes connect, leaving spaces between them called filtration slits that are covered by the slit diaphragm. The GBM is composed of the lamina rara externa, lamina rara interna, and lamina densa. The parietal layer of Bowman's capsule is comprised of simple squamous epithelium. It is separated from the visceral layer by Bowman's space. Mesangial cells are located throughout the renal corpuscle outside of the capillaries. The juxtaglomerular apparatus consists of specialized mesangial cells outside of the renal corpuscle, juxtaglomerular cells, and the macula densa. The thick ascending limb returns to its original glomerulus, forming specialized cells bordering the afferent arteriole termed the macula densa.[9][7][10]

The kidneys perform several important functions including excretion of waste products such as ammonia and urea, electrolyte regulation, and acid-base balance. They play a vital role in the control of blood pressure and the maintenance of intravascular volume via the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. They are responsible for the reabsorption of amino acids, electrolytes, calcium, phosphate, water, and glucose, as well as the secretion of the hormones calcitriol and erythropoietin. [8][7][6]

Embryology

The mammalian kidney develops from the intermediate mesoderm. Kidney development (nephrogenesis) develops in three successive phases: the pronephros, mesonephros, and metanephros. The pronephros, located in the cervical region, is composed of vestigial excretory units (nephrotomes) at the beginning of the fourth week of development that regress by the end of the fourth week. As the pronephros regresses, the mesonephros derives from the intermediate mesoderm from the upper thoracic to upper lumbar segments. It is composed of excretory units that lengthen, form a loop, and develop capillaries to form a renal corpuscle (glomerulus surrounded by Bowman's capsule). The excretory tubule is received by a collecting duct termed the mesonephric or Wolffian duct. Two bilateral organs are present by approximately the sixth week.[11]

The metanephros, primordia of the permanent kidney, appears in the fifth week and is composed of excretory units derived from metanephric mesoderm. The Wolffian duct evaginates to form the ureteric bud, which is stimulated by the interaction between its tyrosine kinase inhibitor RET and glial-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) and between its tyrosine kinase inhibitor MET and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF). The production of GDNF and HGF are regulated by WT1, a transcription factor expressed by the metanephric mesenchyme.[12][11] Mutation in the WT1 gene on 11p13 causes Wilms tumor and is associated with other syndromes.[13] Failure of the interaction between the ureteric bud and mesenchyme, which can be caused by a mutation in the genes that regulate GDNF, can cause renal agenesis and Potter's syndrome.[11] Under normal physiologic conditions, the signaling interaction causes ureteric bud dilation to become the renal pelvis and ureter and then split into major calyces by the end of the sixth week. Early splitting of the ureteric bud can cause bifid ureter. Buds then derive from the calyces that are stimulated to divide into tubules at seven weeks and are absorbed by developing tubules in the periphery, becoming the minor calyces. Successive generations of collecting tubules continue to develop and converge to become renal pyramids. The tubules induce the metanephric tissue cap via fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2) and bone morphogenetic protein 7 (BMP7) to form S-shaped tubules and capillaries that become glomeruli. [13][12][11]The distal glomerulus connects with the connecting tubules and the proximal glomerulus develops into a surrounding Bowman's capsule. The tubule lengthens into the proximal convoluted tubule, loop of Henle, and distal convoluted tubule. These tubules and renal corpuscles altogether comprise the functional excretory unit (nephron). The nephrons are functional and urine-producing by the twelfth week and continue to form until there are approximately 1 million per kidney at birth.[11][14][12][13]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

About 20% of the total cardiac output goes to the kidneys. These highly vascular organs are supplied via the renal arteries, which branch off of the aorta inferior to the superior mesenteric artery and enter the hilum of the kidney at L2. The longer right renal artery passes posterior to the inferior vena cava (IVC). Both of the renal arteries divide close to the renal hilum giving off five segmental arteries. The first branch is the posterior segmental artery, and it supplies the posterior segment of the kidney. The remaining 4 main segmental arteries all arise from the anterior branch of the renal artery and are named according to the segment of the kidney they supply: the superior segmental artery, the anterosuperior segmental artery, the anteroinferior segmental artery, and the inferior segmental artery. Accessory renal arteries, leftover embryologically in approximately 25% of people due to failure of vessel degeneration, may arise from the aorta or renal artery and usually enter the poles.[15][16][17]

The renal veins follow the path of the renal arteries anteriorly. Of note is that the left renal vein is a few centimeters longer than the right vein as it has to cross the midline from the left side to reach the inferior vena cava at the level of L2 or L3. Thus for transplants, the left kidney is usually selected as a graft as it has a longer length vein. In most cases, the left gonadal vein drains into the left renal vein inferiorly. The left renal vein also receives the left suprarenal vein and left inferior phrenic vein. Branches of the lumbar or hemiazygos vein join the left renal vein in 75% of people. The left renal vein passes posterior to the superior mesenteric artery and anterior to the aorta to reach the inferior vena cava, placing it at risk of compression between the two arteries and resulting in renal vein entrapment syndrome. Conversely, on the right side, the gonadal and renal veins separately drain into the inferior vena cava in most cases. Finally, the kidneys are drained by lymphatics, sometimes joined by the lymphatics draining the proximal ureters, which enter the aortic lymph nodes on the left and the right lateral inferior caval lymph nodes on the right.[18][19][20][21]

Nerves

Innervation to the kidneys, and a portion of the proximal ureters and suprarenal glands,[21][4] is communicated via the renal nerve plexus consisting of sympathetic and parasympathetic fibers. This plexus is supplied by fibers from the abdominopelvic splanchnic nerves. Sympathetic efferents innervate the nephrons and renal vasculature entirely, concentrated heavily around the afferent arterioles, thick ascending limbs, and distal convoluted tubules. The sensory renal afferent nerves are situated primarily in the renal pelvis, following along the renal artery or proximal ureter to the pelvic wall, and serve an important role in sympathetic outflow and blood pressure regulation. Some travel along the ureter or pelvis in a parallel fashion, while others are oriented circumferentially. They innervate the pelvic wall, renal artery, and renal vein. No sensory fibers are found in the medulla, and few can be observed in the cortex. [22][23]Visceral afferent fibers transmit pain sensation along the sympathetic fibers to the spinal ganglia and cord segments T11-L2. Pain is often sensed in the corresponding dermatome; thus, flank pain can be referred pain from the corresponding kidney. Renal pain is typically caused by obstruction and dilation, inflammation, infection, or ischemia. Non-obstructing stones in the kidney are generally not the cause of any renal pain or colic.[24]

Surgical Considerations

All of the arteries in the kidneys are end arteries which means there are no renal arterial collaterals. This also means it is necessary to protect any branches or accessory arteries to the kidneys to avoid loss of parenchymal function. Accessory renal arteries should be considered during aortic interventions, obstetric and gynecologic surgery, and renal surgery, including renal transplant.[15]

Brodel's line is the relatively avascular line between the renal anterior and posterior end arteries. It runs longitudinally from superior to inferior and is located just posterior to the lateral convex border of each kidney. Its importance is that this is the ideal location to place a nephrostomy or to perform a renal incision to minimize blood loss.

The retroperitoneum is an enclosed space separate from the peritoneal cavity. When the kidney is injured or traumatized, it is usually wise not to open the retroperitoneum as this will cause a loss of the tamponade effect and may ultimately result in the surgical removal of a kidney that could otherwise have been saved.

The retroperitoneal space is located between the posterior parietal peritoneum medially and the transversalis fascia laterally. It is divided into 3 spaces by the perirenal fascia: the anterior pararenal space, the perirenal space, and the posterior pararenal space.

Clinical Significance

Kidney disease is defined as the presence of an abnormal process or function in the kidney(s).[25][26][19]

- Nephrosis is non-inflammatory nephropathy.

- Nephritis is an inflammatory kidney disease.

- Nephrology is a medical specialty that deals with kidney function and disease.

- Urology is the specialty that deals with surgical problems associated with the kidney.