[1]

Clarke B. Normal bone anatomy and physiology. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2008 Nov:3 Suppl 3(Suppl 3):S131-9. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04151206. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 18988698]

[2]

Dallas SL, Prideaux M, Bonewald LF. The osteocyte: an endocrine cell ... and more. Endocrine reviews. 2013 Oct:34(5):658-90. doi: 10.1210/er.2012-1026. Epub 2013 Apr 23

[PubMed PMID: 23612223]

[3]

Corradetti B, Taraballi F, Powell S, Sung D, Minardi S, Ferrari M, Weiner BK, Tasciotti E. Osteoprogenitor cells from bone marrow and cortical bone: understanding how the environment affects their fate. Stem cells and development. 2015 May 1:24(9):1112-23. doi: 10.1089/scd.2014.0351. Epub 2015 Mar 6

[PubMed PMID: 25517215]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[4]

Caetano-Lopes J, Canhão H, Fonseca JE. Osteoblasts and bone formation. Acta reumatologica portuguesa. 2007 Apr-Jun:32(2):103-10

[PubMed PMID: 17572649]

[5]

Aarden EM,Burger EH,Nijweide PJ, Function of osteocytes in bone. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 1994 Jul

[PubMed PMID: 7962159]

[6]

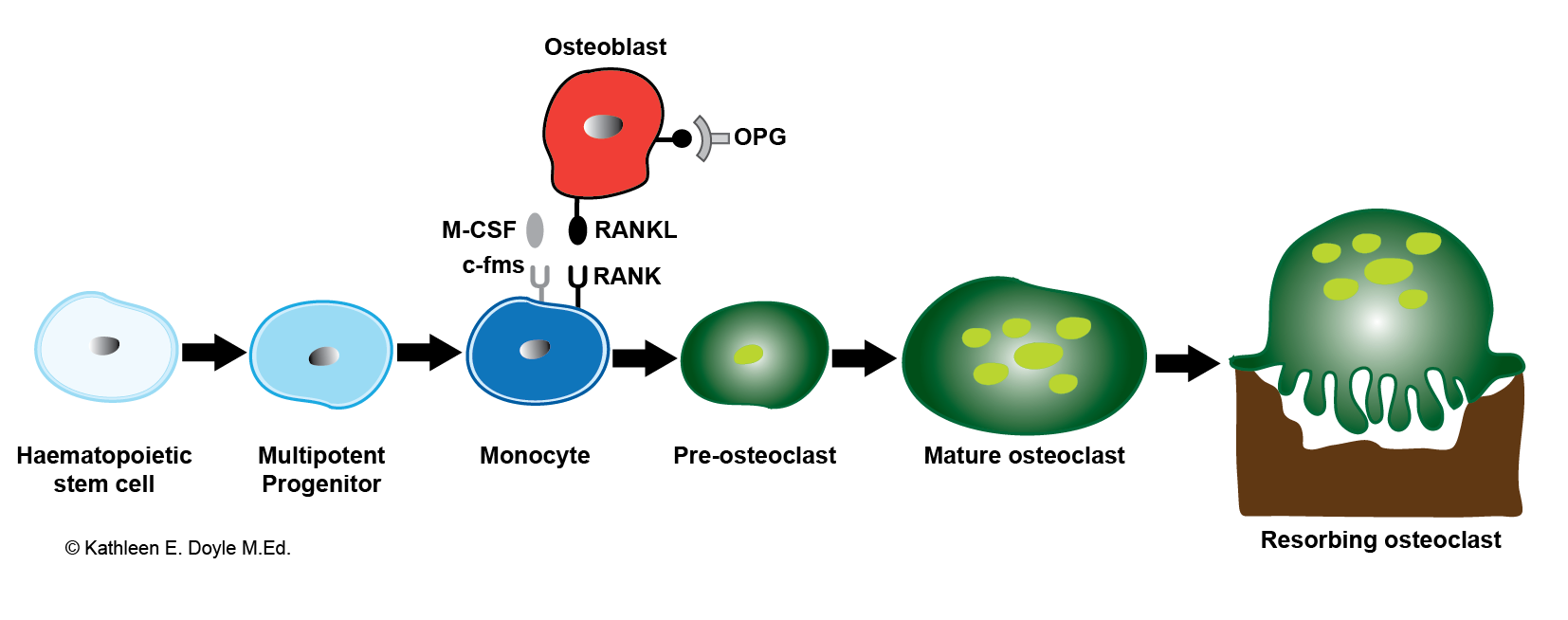

Boyce BF, Yao Z, Xing L. Osteoclasts have multiple roles in bone in addition to bone resorption. Critical reviews in eukaryotic gene expression. 2009:19(3):171-80

[PubMed PMID: 19883363]

[7]

Feng X. Chemical and Biochemical Basis of Cell-Bone Matrix Interaction in Health and Disease. Current chemical biology. 2009 May 1:3(2):189-196

[PubMed PMID: 20161446]

[8]

Hadjidakis DJ, Androulakis II. Bone remodeling. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2006 Dec:1092():385-96

[PubMed PMID: 17308163]

[9]

Feng X, McDonald JM. Disorders of bone remodeling. Annual review of pathology. 2011:6():121-45. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130203. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 20936937]

[10]

Henriksen K, Bollerslev J, Everts V, Karsdal MA. Osteoclast activity and subtypes as a function of physiology and pathology--implications for future treatments of osteoporosis. Endocrine reviews. 2011 Feb:32(1):31-63. doi: 10.1210/er.2010-0006. Epub 2010 Sep 17

[PubMed PMID: 20851921]

[13]

Varacallo MA, Fox EJ. Osteoporosis and its complications. The Medical clinics of North America. 2014 Jul:98(4):817-31, xii-xiii. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2014.03.007. Epub 2014 May 9

[PubMed PMID: 24994054]

[14]

Varacallo MA, Fox EJ, Paul EM, Hassenbein SE, Warlow PM. Patients' response toward an automated orthopedic osteoporosis intervention program. Geriatric orthopaedic surgery & rehabilitation. 2013 Sep:4(3):89-98. doi: 10.1177/2151458513502039. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 24319621]