Introduction

Located in the posterior aspect of the lower leg, the Achilles tendon is the thickest tendon in the human body with the ability to resist large tensile forces. It attaches the muscles of the posterior calf, namely the confluence of the distal attachment of the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles to the calcaneus. Originally named after Achilles, a character in Greek mythology, this tendon is also termed the calcaneal tendon, referring to its attachment. However, its more common name is the Achilles tendon.[1][2][3]

Structure and Function

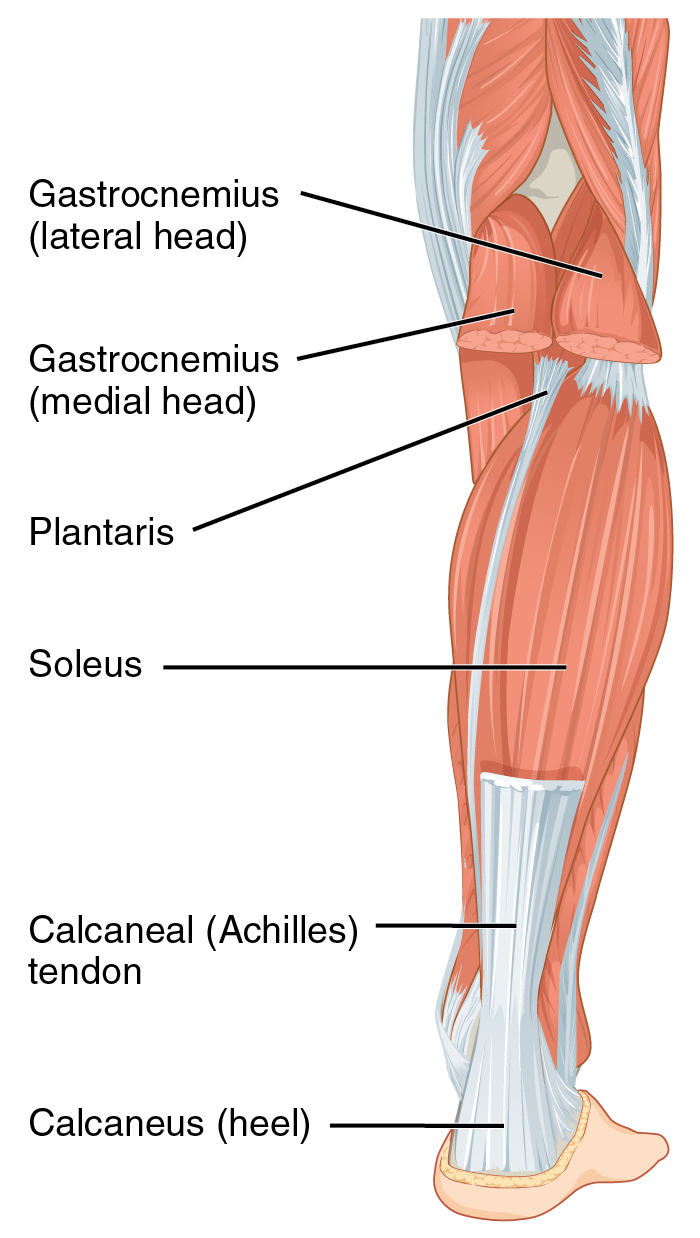

The gastrocnemius muscle is a biarticular muscle that originates on the posterior aspect of the femur along the medial and lateral condyles, forming both medial and lateral heads. Deep to it is the soleus muscle, which originates on the posterior surface of the fibula and medial border of the tibia. Together, both muscles form the superficial posterior compartment of the leg. Distally, these two muscles coalesce to form the common Achilles tendon, which inserts on the middle part of the posterior surface of the calcaneus. The tendon turns 90 degrees medially on its path towards the heel.

Contraction of the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles translates a force through Achilles tendon, causing plantar flexion of the foot; this allows for lower limb locomotion and propulsion in actions such as walking, running, and jumping. During these motions, the Achilles tendon is subject to the highest loads in the body, with tensile loads up to ten times the body's weight.

Specific characteristics of the Achilles tendon allows for these actions. The Achilles consists mainly of type II fast-twitch fibers, and its elasticity allows for rapid propulsion. The tendon is composed primarily of type I collagen and elastin, with the former being responsible for the strength of the tendon. Spiralization of the tendon fibers allow for concentrated stress and may confer a mechanical advantage. Lastly, the Achilles tendon does not have a true synovial sheath but instead is surrounded by a paratenon. The paratenon is made up of a loose connective tissue sheath surrounding the entire tendon and can stretch to 2 to 3 cm with movement to allow for the greatest possible gliding action.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The blood supply of the Achilles tendon consists mainly of longitudinal arteries that course the length of the tendon. Two main blood vessels supply the tendon. The posterior tibial artery supplies both the proximal and distal sections. The peroneal artery supplies the middle section.[4]

Overall, the tendon has a relatively poor blood supply throughout its length, as measured by vessels per cross-sectional area. Also, there is a relatively hypovascular area in the midsection, which correlates to the location of many injuries: the area approximately 2 to 6 cm from the tendon's insertion point. Some have also suggested that poor vascularity contributes to diminished healing after trauma. Blood supply to the tendon also diminishes with age.

Nerves

Gastrocnemius muscle innervation receives its nerve supply from the tibial nerve (S1, S2); the soleus receives neural supply from the tibial nerve (L4, L5, S1, S2). Cutaneous innervation is also from the tibial nerve. The Achilles tendon is innervated mainly by the sural nerve (sensory contribution), with minor contributions from other smaller branches of the tibial nerve. Testing of the Achilles deep tendon reflex is common and involves bluntly hitting the tendon, ordinarily causing plantar flexion of the foot. This test assesses the sacral nerve roots S1 and S2.

Clinical Significance

While the Achilles tendon is the strongest in the body, it is prone to injury and is the most commonly ruptured tendon. Achilles tendonitis is a common presentation among running and jumping athletes. Chronically, the Achilles tendon may develop tendonosis where no inflammatory process exists, but chronic remodeling may occur.[5][6][7]

Inflammation (tendinitis or tendinopathy)

Achilles tendon tendinitis is a common overuse injury in individuals who participate in running and jumping sports. While the term tendinitis denotes inflammation, this has not been evident histologically. Therefore, it is sometimes called tendinopathy, and these terms are interchangeable.

Etiology often has links with increased or overuse, lack of flexibility, or a stiff Achilles tendon. It occurs as a result of compressive or tensile overload and straining during physical exercise. Repetitive microtrauma can cause friction between the gastrocnemius and the soleus leading to frictional forces and subsequent inflammation or degeneration of the tendon. Other risk factors may include inadequate local vascular supply, nutrition, and persistent inflammatory response. Acute trauma from tendon overload may lead to a strain and subsequent tendinopathy.

Most patients will present with pain along the Achilles tendon. The pain is worse with an active or passive range of motion, including stretching the tendon. The tendinopathy can be described by where it localizes, either midportion or at its distal attachment. Swelling and ecchymosis are not the expected presentation.

Management of Achilles tendinopathy varies by the clinician; this includes but is not limited to orthotics, physical therapy, topical steroids and iontophoresis, soft tissue treatments, extracorporeal shock wave therapy, anti-inflammatory medications, peritendinous corticosteroid injections, platelet-rich plasma injections, and surgery.

Degeneration (tendinosis)

Tendinosis is the chronic, diffuse thickening of the tendon and histological evidence of degeneration in the absence of acute injury or clinical signs of inflammation. The pathophysiology of Achilles tendon tendinosis appears to be repetitive microtrauma with a relative lack of healing due to the limited vasculature. The Achilles tendon thickens in response to this activity, which is visible on imaging such as MRI and ultrasound and may result in a palpable nodule at the Achilles tendon.

This condition becomes more common with age, especially in those over 35 years. Aging plays a role in tendinosis, as aging leads to decreased blood supply. Aging also reduces cell density and decreases collagen fibril density, with an overall loss of fiber waviness, which may predispose the tendon to injury.

Lastly, while it frequently involves the hypovascular portion of the Achilles tendon, it may also involve the insertion of the tendon, known as an enthesopathy. Enthesopathy often correlates with other inflammatory conditions such as gout and seronegative spondyloarthropathies. Enthesopathy may be evident on radiographs with so-called "bone spurring" or enthesophytes visible on the calcaneal attachment.

Management of Achilles tendinosis is similar to Achilles tendonitis.

Rupture

Achilles tendon ruptures represent a spectrum of partial-thickness to complete thickness tears. Tendon ruptures occur when there is a sudden force placed on the Achilles tendon, typically an eccentric load or explosive plyometric contraction. Other movements, such as pivoting, may cause a rupture. The majority of ruptures occur during recreational sports and athletic events; however, rupture can occur in nonathletes and sedentary individuals.

Due to the strength and elasticity of the tendon, patients often complain of a sudden "pop" during rupture. Commonly, patients feel as if they were struck or pushed at the level of the ankle. The provider may appreciate swelling, bruising, and/or a visible defect in the tendon when compared to the unaffected leg. In partial tears, they may have pain with intact plantar flexion. In the Thompson test, squeezing the calf should normally elicit plantar flexion, but this motion may become diminished or absent in tendon rupture. Conversely, the presence of a plantar-flexion mechanism does not definitively exclude a partial tear or rupture.

The Achilles tendon is vulnerable to injuries due to areas of limited blood supply and its subjection to strong forces. The tendon becomes increasingly stiff as individuals age. Intrinsic risk factors for rupture include subtalar hyperpronation, excessive forefoot or hindfoot varus or valgus, the inflexibility of the triceps surae at the musculotendinous junction, leg length discrepancy, muscle imbalance, muscle fatigue, excess weight or obesity, and age. Extrinsic risk factors include primarily incorrect running and jumping techniques, improper footwear, and improper training. Certain medications have been implicated, such as steroids and fluoroquinolones.

Overall, the incidence of Achilles tendon rupture is 12 per 100,000 individuals. The typical age is between 40 and 50 years old. The male to female ratio ranges from 2 to 1 to 12 to 1. Management of Achilles tendon rupture varies. For active individuals or professional athletes, surgical intervention is often a therapeutic option. In individuals with partial tears, older individuals, or people who are poor surgical candidates, conservative therapy with immobilization, rest, and progressive physical therapy may be a consideration.

Other

In those with lipid metabolism disorders such as familial hypercholesterolemia, large lipid deposits may appear in the area as Achilles tendon xanthomas. Patients may develop symptoms of tendinopathy or tenosynovitis before clinically evident xanthomas.