Introduction

Puberty is the process of physical maturation where an adolescent reaches sexual maturity and becomes capable of reproduction. On average, puberty typically begins between 8 and 13 in females and 9 and 14 in males. Puberty is associated with emotional and hormonal changes, as well as physical changes such as breast development in females (thelarche), pubic hair development (pubarche), genital changes in males, voice changes, an increase in height, and the onset of menstruation (menarche). Puberty proceeds through five stages, termed Tanner stages, ranging from prepubertal, to full maturity.

Issues of Concern

In general, puberty follows a predictable pattern of onset and sequence. However, due to differences in each individual, including environment and genetics, puberty may proceed in a less-than-predictable way. Issues of concern related to puberty include, but are not limited to delayed puberty, precocious (early) puberty, contrasexual pubertal development, premature adrenarche (androgens causing early pubertal changes), premature thelarche in girls, and premature or delayed menarche.

Of specific concern to adolescent males is the appearance of enlarged breasts during puberty. Gynecomastia of puberty is a benign condition in males, characterized by the proliferation of glandular elements, which results in the enlargement of one or both breasts. During male puberty, there is often a short-lived imbalance between estrogen and testosterone, leading to gynecomastia. If the history and physical examination fall within normal limits, the gynecomastia usually resolves on its own by the age of 18, and only reassurance and monitoring are necessary.[1]

Puberty can also bring about emotional changes and stress to individuals as they come to terms with their changing bodies. Voice changes, wet dreams, involuntary erections, and noticeable physical changes such as breast enlargement, acne, widened hips, and growth spurts can cause adolescents to become worried and concerned about being different from their peers. While it is important to recognize the physiologic changes in puberty, it is also important to acknowledge the psychosocial and emotional changes that may occur at this time.

Cellular Level

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) neurons of the hypothalamus control the initiation of puberty. The pulsatile secretion of GnRH by these neurons brings about the physiologic changes associated with puberty. Currently, there are increasing amounts of evidence showing that kisspeptin neurons in the arcuate nucleus release neurokinin B and dynorphin to generate the pulsatile secretion of GnRH.[2] GnRH causes the release of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) from the gonadotropic cells of the anterior pituitary gland. FSH and LH affect the Leydig and Sertoli cells in the testes and the theca and granulosa cells of the ovary. The zona reticularis of the adrenal cortex produces the hormones responsible for adrenarche and function separately from the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis.[3]

Development

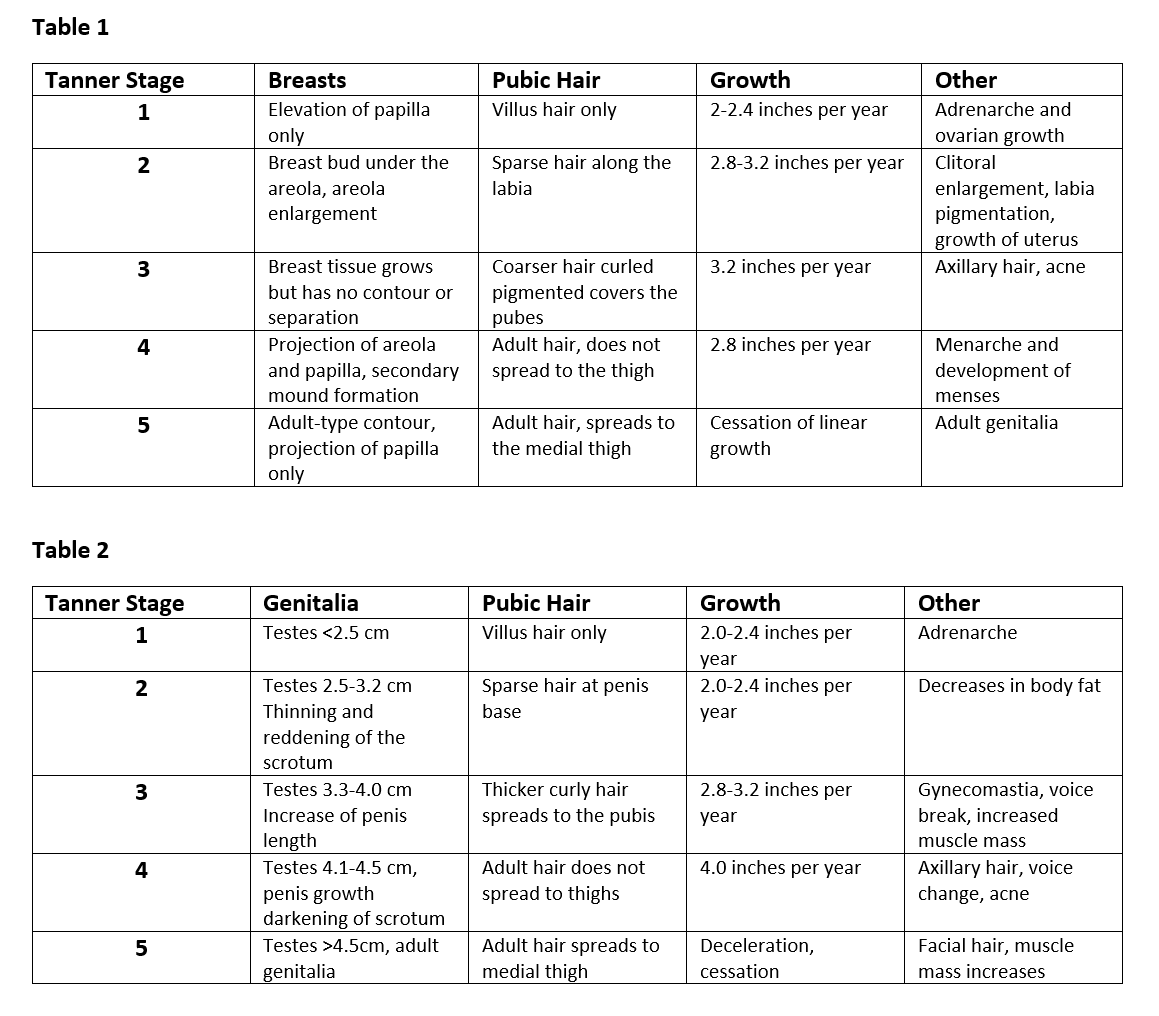

Tanner staging is a classification system used to assess stages of puberty. A breakdown of each stage can be seen in Tables 1 and 2.

Female Development During Puberty[4]

- Thelarche

- Thelarche refers to breast growth, typically the first sign of puberty in girls, occurring around 9 or 10. An increase in estrogen causes the lactiferous duct system to develop, while an increase in progesterone causes the lobular alveoli at the ends of lactiferous ducts to increase in number.

- Pubarche

- Approximately six months after thelarche begins, pubarche, or growth of pubic hair, will typically occur. Pubic hair initially appears light, sparse and straight but will become coarse, thick, and dark throughout the course of puberty. Approximately two years after pubarche, axillary hair will begin to grow, a secondary sexual characteristic mediated by testosterone.

- Menarche

- Menarche is the female's first menstrual period, caused by an increase in FSH and LH. Menarche typically occurs 1.5 to 3 years after thelarche at approximately 12.8 years of age in White race girls and 3-8 months later in African-American girls. During puberty, the uterine endometrium undergoes cycles of proliferation and regression due to fluctuating plasma estradiol levels. This occurs until a point is reached when substantial growth occurs so that withdrawal of estrogen results in the first menstruation (menarche). Plasma progesterone levels remain low until a rise occurs after menarche, indicating that ovulation has occurred. The first ovulation takes place approximately 6 to 9 months after menarche due to an immature positive feedback mechanism of estrogen.

- Ovarian Development

- The rise in gonadotropins during puberty stimulates the ovary to produce estradiol, which is responsible for developing secondary sexual characteristics such as thelarche, growth of reproductive organs, fat redistribution to the hips and breasts, and bone maturation. Ovarian size increases from prepubertal volume (approximately 0.5 cm^3) to a postpubertal volume (approximately 4.0 cm^3).

- Uterus Size

- The uterus of a prepubertal female is tear-drop shaped, with the neck and isthmus accounting for up to two-thirds of the uterine volume. An increase in estrogen production causes the uterus to become pear-shaped, with the uterine body increasing in length and thickness.

- Vaginal Changes

- Puberty brings about an enlargement of the labia major and labia minora. Clear to white vaginal discharge may also be seen prior to the onset of menarche.

Male development during puberty[5]

- Testicular Size

- An increase in testicular size is typically the first sign of puberty in boys. Testes increase in size during puberty due to the development of the seminiferous tubules. Increased LH stimulates the synthesis of testosterone by Leydig cells, while increased FSH stimulates the production of sperm by Sertoli cells. Testicular size increases throughout puberty up to Tanner stage 4, at which time the adult longitudinal diameter and volume are reached. An increase in testicular size causes the scrotal skin to become thinner and darker in color. Boys typically experience their first ejaculation approximately one year after the testicles begin to grow. The first ejaculation, however, does not automatically signal an ability to procreate. On average, fertility is achieved one year after the first ejaculation.

- Pubarche

- The growth of pubic hair at the penile base typically occurs alongside testicular development. Pubic hairs initially appear light, straight and thin; then become darker, curlier, and thicker as puberty progresses. Approximately two years after the onset of pubarche, axillary, chest, and facial hair begin to grow.

- Penis Size

- The growth of the penis occurs after testicular enlargement. The penis grows in length, then width, and the glans penis and corpus cavernosum also enlarge.

Growth Spurt[6]

The growth spurt results from interactions between sex steroids (estradiol/testosterone), growth hormone, and IGF-1. The rise in sex steroids leads to an increase in growth hormone levels, which causes an increase in IGF-1. IGF-1 causes somatic growth via its metabolic actions (e.g., increases trabecular bone growth). Following the growth spurt in males, the larynx and vocal cords enlarge, and the boy's voice may 'crack' as it deepens in pitch.[7]

Adrenarche

Adrenarche refers to the increased secretion of adrenal androgen precursors dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS), and androstenedione from the adrenal zona reticularis, which typically occurs prior to puberty in children around the ages of 6-8 years. The eventual phenotypical result of adrenarche is pubarche, as well as apocrine odor, increased oiliness of hair and skin, and acne.[8]

Organ Systems Involved

The two major systems involved in puberty are the reproductive and endocrine systems. The hypothalamus, pituitary gland, adrenal glands, ovaries, and testes all produce hormones involved in the changes of puberty. However, these hormones produced during puberty affect nearly every system within the body, causing both internal and observable changes. The skeletal system changes, muscles grow, the circulatory and respiratory systems undergo rapid growth and development, and nervous system changes occur. During puberty, increases in estrogen and testosterone bind receptors in the limbic system, which stimulates the sex drive and increases emotional volatility and impulsivity.[9]

Function

The primary function of puberty is to produce sexually mature adults capable of reproduction.

Mechanism

The hypothalamus releases GnRH in a pulsatile manner, which then stimulates the release of FSH and LH from the anterior pituitary gland. Prior to puberty, FSH and LH levels in the body are low. Approximately one year before the onset of puberty, CNS inhibition of GnRH subsides, leading to a rise in the release of FSH and LH.[10]

FSH and LH act on the gonads (ovaries and testicles) to stimulate the synthesis and release of sex steroid hormones (estrogen/progesterone and testosterone) and support gametogenesis (formation and development of oocytes/sperm). Sex steroids exert negative feedback on the hypothalamus and pituitary gland to ensure circulating levels remain stable. A rise in FSH stimulates an increase in estrogen synthesis and oogenesis in females and the onset of sperm production in males. A rise in LH stimulates an increase in progesterone production in females and an increase in testosterone production in males. Hormonal changes caused by rises in FSH and LH allow for the physical changes of puberty to begin. The first hormonal change showing puberty may be imminent is the appearance of pulsatile LH release during sleep. At the end of puberty, a difference between sleep and wake LH secretory patterns is not seen.[11]

Growth hormone (GH) stimulates FSH-induced differentiation of granulosa cells, increases ovarian levels of IGF-1, and amplifies the ovarian response to gonadotropins. The puberty of patients with isolated GH deficiency is frequently delayed, Leydig cell function is diminished, and the response to chorionic gonadotropins decreases. GH administration can restore testicular responsiveness to LH and Leydig cell steroidogenesis.

Serum prolactin concentration increases during female puberty but remains relatively stable throughout male puberty. Insulin is essential for normal growth, and levels rise noticeably during puberty, with a strong positive correlation with IGF-1.

Related Testing

The first-line assessment for any child experiencing issues with pubertal development is a thorough history and physical exam. The history will allow the healthcare practitioner to gain insight into any possibility of a genetic cause and will provide vital information about the child’s growth pattern and development to date. It may also give clues to other causes of pubertal disorders such as poor nutrition, underlying disease, excessive exercise, or exogenous steroids. The physical exam should include examining the genitalia and the breasts in girls to determine Tanner staging. Tanner staging is a standard system used to categorize the different stages of pubertal development a child has achieved. For boys, Tanner staging includes testicular and penile growth, pubic hair distribution, and linear growth. In girls, Tanner staging includes breast development, pubic hair distribution, and linear growth. In addition to Tanner categorizations, examining the optic fundus and determining if the sense of smell is intact can be helpful. Standardized growth charts tracking the child’s growth over time are also useful in determining if a child is developing appropriately.[12]

Skin lesions noted on the physical exam can also point toward specific causes of abnormal puberty, such as McCune-Albright Syndrome. An X-ray of the left wrist is commonly used to determine bone age and whether the child’s bone maturation is more advanced than their age, suggesting they may be going through premature puberty. In addition to an x-ray of the left wrist, central nervous system (CNS) imaging may be performed if there are signs of CNS involvement. Measurement of hormone levels may also be helpful in the presence of abnormal puberty. Levels of estradiol, testosterone, FSH, and LH can be measured by checking for the presence of pubertal or prepubertal levels. A GnRH stimulation test is also helpful to determine a central or peripheral cause. This test involves administering 100 micrograms of GnRH after overnight fasting and observing FSH, LH, estradiol, and testosterone levels at 15, 30, 45, and 60 minutes post-injection. The stimulation test will cause activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis in central causes resulting in increased levels of the hormones; a peripheral cause will not increase hormone levels.[13]

Additional testing may include thyroid hormone levels (TSH, T3, T4), blood glucose levels, a complete blood count, liver enzymes, and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate. A karyotype analysis may also be performed, which will show the patient’s chromosomal pattern and helps determine if there is a genetic cause, such as Turner syndrome or Klinefelter syndrome. Although the clinician may evaluate many other factors after a history and physical, the testing should be tailored individually for each child’s presentation and the most likely cause of their abnormal puberty.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of puberty can be broken down into three main categories: premature (precocious) puberty, delayed puberty, and contrasexual development.

Precocious Puberty

Precocious puberty, or early development of secondary sexual characteristics, is defined as the appearance of secondary sexual characteristics prior to the age of eight in girls or before the age of nine in boys. Precocious puberty can be broken down by pathological location into central or peripheral precocious puberty. Central precocious puberty (CPP) involves activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis, which leads to early but normal pubertal development. CPP is more common in girls, and while most cases are idiopathic, it can be caused by neoplasm, radiation, head trauma, or genetic conditions.[14] Peripheral precocious puberty (PPP) results from an increase in sex steroids that does not come from activation of the HPG axis. Findings in PPP patients typically include a rapid and atypically sequenced pubertal progression. The most notable causes of PPP include McCune-Albright syndrome and testotoxicosis.[15]

Many causes of early pubertal development are shared among girls and boys; however, some causes of early puberty are unique to each of the sexes.[16] The causes of precocious puberty shared by either gender include benign premature adrenarche, central nervous system (CNS) and pituitary lesions, constitutional and idiopathic precocious puberty, McCune-Albright syndrome, and exogenous sex hormones.

-

Premature adrenarche correlates with the premature presence of pubic or axillary hair and possibly increased sebaceous gland activity, without other signs of puberty present, usually before six years of age. This is typically an isolated abnormality, and most children go on to develop the other signs of puberty at a normal age. Plasma DHEAS is usually elevated to pubertal levels, while FSH, LH, estradiol, and testosterone are typically at levels found in prepubertal children. Other studies, such as a GnRH stimulation test, will show prepubertal results. An ACTH stimulation test may help exclude congenital adrenal hyperplasia, which may present with similar symptoms.[13]

-

CNS and pituitary lesions will typically present with normal but early occurring stages of puberty, and children may present with a bone age greater than their chronological age. Additionally, these lesions may cause other problems to develop, such as visual field defects. If a CNS or pituitary lesion is suspected, an MRI of the brain should be ordered to confirm or rule out this diagnosis.

-

Constitutional/idiopathic precocious puberty can occur in males and females but tends to be more prevalent in females. Precocious or premature puberty is considered idiopathic when a child has no familial links to premature development, and there is no other cause that explains the premature development of puberty. Constitutional precocious puberty can be linked to a familial tendency toward early development. Children with these disorders will respond to a GnRH stimulation test with pubertal levels of sex hormones, including FSH and LH. These children may have a bone age that is much higher than their chronological age. Additionally, all other causes of premature puberty must be ruled out, such as CNS pathology and elevated adrenal hormones.[13]

-

McCune-Albright Syndrome is associated with cafe-au-lait spots, polyostotic fibrous dysplasia, precocious puberty, and may be associated with other endocrine disorders. Precocious puberty seen in McCune-Albright syndrome manifests in early childhood, with sudden onset vaginal bleeding typically the initial sign of the condition. Individuals may begin to experience vaginal bleeding as early as two years of age.[17]

-

Exogenous sex hormones in substances such as oral contraceptives and anabolic steroids can cause secondary sexual characteristics to develop. These causes can usually be ruled in or out rather quickly by performing a urinalysis, as the metabolites of exogenous hormones can be found in the urine. Additionally, children who have an exogenous hormone source and are not undergoing natural puberty will lack pubic hair. Girls may have darkened areolas, and boys will have small testicles resembling the size of a prepubertal child.[13]

Causes of premature puberty unique to males include gonadotropin-secreting tumors and testotoxicosis.

- Gonadotropin-secreting tumors typically secrete hCG-like components that can have a similar function in signaling to LH, resulting in an incomplete type of premature puberty in boys. Girls, however, need FSH to increase estrogen production in the ovaries and thus, will not have premature development due to this type of tumor alone. Examples of tumors that might produce hCG are hepatomas, teratomas, and germinomas of the pineal gland.[13]

- Testotoxicosis is a cause of peripheral precocious puberty in which boys present with early-onset puberty between 2 and 4 years of age. Patients experience early development of secondary sexual characteristics, accelerated growth, and diminished adult height. The cause of testotoxicosis is linked to a heterogenous constitutively activating mutation of the LHCGR gene encoding the luteinizing hormone receptor. Laboratory analysis will show an increased level of sex steroids in the setting of low LH levels.[18]

Delayed Puberty

Delayed puberty is the lack of physical evidence of puberty by 2 to 2.5 standard deviations above the mean age for the initiation of puberty. In boys, this is considered a period longer than four years between the first signs of testicular enlargement and the end of puberty or the absence of testicular growth by 14 years old. Delayed puberty in girls is considered the absence of breast growth by 13 years of age or more than four years between thelarche and menarche. The causes of delayed puberty include hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, hypergonadotropic hypogonadism, hypopituitarism, chromosomal abnormalities, and hypothalamic dysfunction due to secondary causes.[19]

- Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism is due to a hypothalamus or pituitary gland disorder, resulting in GnRH, LH, or FSH deficiency. Several causes of hypogonadotropic hypogonadism exist, including damage to the hypothalamus or pituitary gland from surgery, tumor, infection, or injury. Genetic defects, severe stress, and long-term use of opioids or glucocorticoids can also be a cause. Additionally, nutritional problems and iron overload may also cause hypogonadotropic hypogonadism.

- Constitutional delay of growth and puberty is a transient state of hypogonadotropic hypogonadism associated with prolongation of the childhood growth phase, delayed skeletal maturation, delayed pubertal growth spurt, and low IGF-1 secretion. On a GnRH stimulation test, these children will have prepubertal levels of FSH, LH, estradiol, and testosterone. Eventually, puberty will spontaneously occur, resulting in the progression of development in these children. In most cases, the final adult height does not meet the predicted adult height, and individuals tend to have a disproportionately short trunk.[20]

- Hypergonadotropic hypogonadism is the failure of the gonads to produce sex hormones. FSH and LH will be elevated due to minimal negative feedback on the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. There can be many causes of gonadal failure, including genetics and physical trauma. In boys, Noonan syndrome and myotonic dystrophy have been known to cause gonadal failure. Additionally, there have been cases of LH beta-receptor mutations reported in boys resulting in a lack of a gonadal response. Trauma to the testes by testicular torsion or cryptorchidism is also a cause of gonadal failure in boys. In females, autoimmune ovarian failure is a possible cause of hypergonadotropic hypogonadism, with the child likely also exhibiting signs or symptoms of other autoimmune conditions. Interestingly, half of the girls with galactosemia have been shown to develop ovarian failure, thought to be due to toxic metabolites.[19]

- Hypopituitarism is a lack of release of hormones from the pituitary gland. Delayed puberty is not the only sign of hypopituitarism, as endocrine dysfunctions such as hypothyroidism, delayed bone growth, and adrenal insufficiency may also be present. Kallman syndrome is a specific disorder falling under hypopituitarism where neurons in the developing brain fail to migrate, resulting in anosmia, the absence of a sense of smell, and a lack of GnRH cells in the hypothalamus.[12]

- Chromosomal abnormalities are a cause of delayed puberty shared by both males and females. In females, Turner syndrome (45 XO) is a common cause of ovarian failure resulting from a missing or incomplete X chromosome. Along with ovarian failure, Turner syndrome has many other identifying characteristics, including but not limited to a webbed neck, short stature or delayed growth, coarctation of the aorta, and a "shield" chest with widely spaced nipples. Females with Turner syndrome will typically present with delayed puberty or primary amenorrhea secondary to ovarian failure. A common chromosomal disorder in males with delayed puberty is Klinefelter syndrome (47 XXY), a chromosomal abnormality resulting from a random genetic error after conception. These patients typically present with small testes, gynecomastia, tall stature, long legs, and short arms. Due to low testosterone, adolescents affected by Klinefelter syndrome will typically undergo delayed or incomplete pubertal development.[12]

- In addition to the above causes of delayed puberty, pubertal delay can also occur in several illnesses where hypothalamic dysfunction can occur. Examples are hypothyroidism, cystic fibrosis, sickle cell disease, celiac disease, and diabetes mellitus.[19] Poor nutrition and long-term glucocorticoid use have also been linked to delayed puberty.

Contrasexual Development

Contrasexual development occurs when male or female children develop physical features of the opposite gender. This condition tends to be more common in girls and is commonly caused by polycystic ovaries and increased responses by the adrenal gland. Girls will have a male-like distribution of hair and may develop hirsutism. Girls can also develop clitoromegaly and lose the contour of the breast mass. Possible causes include Cushing syndrome, acromegaly, exogenous androgens, adrenal tumors, ovarian tumors, and hyperprolactinemia. Although contrasexual development is less common in boys, the cause is typically estrogen-secreting tumors when it does occur.[13]

Clinical Significance

Puberty is a highly significant process and a part of all children’s development into functional adults. During this time, children begin to gain the capacity for reproduction, which is essential to discuss with children as they progress through puberty. Discussion of safe sexual practices is an important aspect of well-child visits and is pertinent to identifying children with unsafe or high-risk sexual encounters. The discussion of sexuality by pediatricians or other medical caregivers with young teens as they progress into adulthood provides a chance for them to speak to someone under confidentiality and ask specific questions to understand better their sexuality as well as what is considered safe sexual practices.[21]

Puberty also coincides with a child’s psychosocial development. Children who may be early or behind in attaining puberty milestones, when compared to their peers, are at a much higher risk of emotional distress and low self-esteem. The ability to monitor the progression of puberty in the pediatric population is vital, as it is essential to their reproductive development and because of the many physical and psychological risks children face during this time in their development.