Introduction

The lungs are the vital respiration organs in the thorax. Healthy human lung tissue is soft, light, and spongy. These characteristics facilitate and allow for elasticity and recoil for normal dynamic function. The lungs subdivide into lung parenchyma (the portion of the lung involved in gas transfer) and bronchi (airways, non-respiratory tissues). The bronchi (singular. bronchus) are an extension of the trachea and serve as the central passageway into the lungs. Together, these two structures form the tracheobronchial tree of the lungs, with its primary purpose being to transport inspired air into the lungs where oxygen-deprived blood becomes oxygenated.[1]

Structure and Function

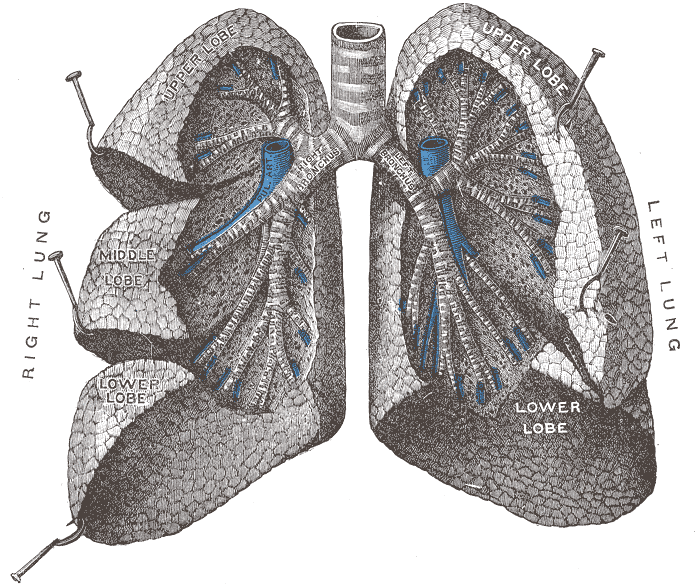

The bronchi (singular. bronchus) extend from the trachea (also called the "windpipe").[2] Together, these two structures form the tracheobronchial tree of the lungs. The trachea is the trunk of the tree located in the superior mediastinum. The bronchi are the branches of the tree within the lungs. Both the trachea and bronchi form part of the conducting zone of the respiratory system. While it is the trachea's purpose to conduct air from the mouth and nose towards the lungs, it is the bronchi which distribute the air throughout the lungs until reaching the respiratory bronchioles and alveolar sacs (these structures pertain to the respiratory zone). The latter serves as the location for carbon dioxide and oxygen gas exchange across the wall (blood-air barrier) of pulmonary capillaries and lung alveoli.

The bronchial structure begins at the transverse thoracic plane (also known as the sternal angle at the fourth thoracic vertebra), where the trachea bifurcates into two main bronchi, one for each lung. The main bronchi (also known as primary bronchi) enter the lungs inferior and lateral through the hila. At the bifurcation, the two main bronchi are not equally divided. The right main bronchus has a wider diameter, is shorter, and lies more vertically relative to the hilum. The left main bronchus has a smaller diameter and is more horizontal; it must pass inferior to the arch of the aorta and anterior to the esophagus and thoracic aorta to reach the left lung's hilum.[3]

The primary (main) bronchi then subdivide into secondary lobar bronchi. There are one secondary lobar bronchi per each lobe of the lung. Thus, the right lung has three secondary lobar bronchi, and the left lung has two secondary lobar bronchi. Following, each lobar bronchi further divides into several tertiary segmental bronchi. Each segmental bronchi supply a bronchopulmonary segment, which are the largest subdivisions of the lobe. There are ten bronchopulmonary segments in the right lung and eight through ten bronchopulmonary segments in the left lung, depending on the segment combinations.[3]

After the tertiary segmental bronchi, the airways continue to fan out into bronchioles. Bronchioles then divide into three types: conducting, terminal, and respiratory. There are 20-25 branching generations of conducting bronchioles after the tertiary segmental bronchi. As the bronchioles become smaller in width, they become terminal bronchioles which mark the end of the conducting zone of the respiratory system. The terminal bronchioles divide further to form several generations of respiratory bronchioles, which are the narrowest airways in the lungs that give rise to alveolar ducts and alveolar sacs (respiratory bronchioles and alveoli form the respiratory zone). Each respiratory bronchiole divides into two through eleven alveolar ducts; each duct gives rise to five through six alveolar sacs.

Anatomical characteristics of the tracheobronchial tree are that it contains cartilage, smooth muscle, and mucosal lining. The trachea has a C-shaped hyaline cartilage while the bronchi have hyaline cartilage plates. Cartilage is crucial for preventing airway collapse during inhalation and exhalation. Going down the bronchial tree, cartilage amount decreases, and smooth muscle increases. Specifically, the bronchioles lack cartilage in their walls and rely on smooth muscle and elastic fibers to maintain their wall integrity. The smooth muscle is also important to control airflow through contraction and dilation of the airway. Finally, the airway is covered by a mucosal lining to protect the lungs and trap foreign substances that enter the body through inhalation.[2]

Histologically, both the trachea and bronchi have a tissue lining of pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium, which contains mucus-producing goblet cells. Going down the bronchial tree to the bronchioles, the epithelium changes to simple cuboidal epithelium containing club cells and no goblet cells. The club cells form surfactant which aid bronchioles to expand during inhalation and avoid bronchial collapse during exhalation. Following, the predominating cell types at the respiratory bronchioles are simple cuboidal epithelium with ciliated cells and Clara cells. Finally, the alveolar cells are simple squamous epithelium.[4]

Embryology

The embryological process of the lung's bronchial tree formation begins when the embryo is four weeks old. At this moment, the embryo already has started gut tube development from the endoderm germ layer. The gut tube divides into foregut, midgut, and hindgut. The first traces of the bronchial tree appear as the respiratory diverticulum (lung bud), which is located ventrally on the foregut as an outgrowth. Lung bud outgrowth depends on the production of retinoic acid by the surrounding mesoderm; retinoic acid upregulates transcription factor TBX4, which promotes lung formation and differentiation. Hence, the interior lining of the bronchi is from endoderm origin while the connective tissue, muscle, and cartilage of the bronchi are from mesoderm origin, specifically splanchnic mesoderm.

As the respiratory diverticulum grows caudally, the bud begins to pinch off the foregut by the tracheoesophageal ridges. These are two longitudinal ridges on either side of the bud that fuse to form the tracheoesophageal septum, thus dividing the esophagus from the developing primitive trachea (lung bud). Further bud growth promotes the development of two lateral outpouchings, known as the primitive bronchial buds. The left and right main bronchi (from the bronchial buds) enlarge at the beginning of the fifth week. Subsequent caudal and lateral bud growth forms the secondary bronchi, which expands into the body cavity. These secondary bronchi subdivide in a dichotomous fashion, thus forming eight tertiary bronchi in the left lung and ten tertiary bronchi in the right. About seventeen generations of divisions have developed by the end of six months. Endoderm-mesenchymal interactions control these branching signals, which involve fibroblast growth factors.

The maturation of the lungs follows the subsequent order. From weeks five up to sixteen, bronchi branching has continued to form terminal bronchioles, which is known as the pseudoglandular period. Then, the canalicular period ranges from week sixteen up to twenty-six. In this period, the terminal bronchioles divide continuously into respiratory bronchioles with alveolar ducts. The terminal sac period is from week twenty-six up to birth. In this stage, the terminal sacs (primitive alveoli) form with close relations to the lung capillaries; this is the beginning of the blood-air barrier. Finally, the time frame from eight months up to childhood is the alveolar period, where alveoli mature.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Blood Supply

It is crucial to understand that the lungs have two types of vasculatures. First, the lungs have the pulmonary arteries, which are a low-pressure system that arises from the right ventricle and takes part in gas exchange. Second, there is a bronchial artery circulation; this arises from the left heart and is part of the systemic circulation. These arteries are a high-pressure system and provide oxygen to lung tissue. The distal-most branches of the bronchial arteries anastomose with branches of the pulmonary arteries. We will discuss the bronchial artery circulation further.

First, the bronchial arteries come off the descending aorta and supply about 1% of lung blood flow. They supply circulation to the upper esophagus, then pass posteriorly to the main bronchi down the brachial tree supplying oxygenated blood to the non-respiratory conducting tissues of the lungs. It also irrigates the visceral pleura, the intrapulmonary blood vessel walls, and the lymphatic system. The bronchial artery's origin varies between person to person; generally, the single right bronchial artery rises from the third or fourth intercostal artery while the two left bronchial artery arises directly from the aorta. The right bronchial artery may also branch from a superior intercostal artery or a left superior bronchial artery.[3]

The bronchial vein receives blood from the bronchi and drains back into the systemic circulation. Nevertheless, it only clears a portion of the blood brought by the bronchial arteries. The blood that remains is carried away by the pulmonary veins. Blood returning from visceral pleura, peripheral lung regions, and distal root components drain into the pulmonary veins. Additionally, the bronchial veins may receive drainage from small vessels from the tracheobronchial lymph nodes. The right bronchial vein drains through the azygous vein and the left bronchial vein into the accessory hemizygous vein or the left superior intercostal vein.

Lymphatics

The lymphatic vessels pick up the fluid that leaks into the bronchial tree, pulmonary vessels, and connective tissue septa and returns it to the circulatory system. It is important to state that the lymphatic vessels are not in the walls of the pulmonary alveoli. The lung's lymphatic plexus originate from two different structures: the superficial subpleural and the deep lymphatic plexuses. Deep into the visceral pleura, is the location of the superficial lymphatic plexus. It drains visceral pleura and lung parenchyma into the bronchopulmonary (hilar) lymph nodes; these are located in the lung's hilum.[3][5]

Located in the bronchi's submucosa and in the peribronchial connective tissue lies the deep lymphatic plexus. Its role is to drain fluid from the root of the lung into the intrinsic pulmonary lymph nodes, which are in the lobar bronchi. Lymph vessel drainage continues to follow the pulmonary vessels and bronchi towards the hilum, where collected fluid also exits into the bronchopulmonary (hilar) lymph nodes. Interestingly, various lymphatics of the left lower lobe drain into the right superior tracheobronchial nodes.[5]

As noted, both superficial and deep lymphatic plexuses drain from the hilum into the superior and inferior (cranial) tracheobronchial lymph nodes (located at the trachea's bifurcation). Then the lymph fluid drains into the tracheal (paratracheal) nodes and later into the right and left bronchomediastinal nodes and trunks. The right bronchomediastinal trunk converges with other lymphatic trunks to form the right lymphatic duct. The left bronchomediastinal trunk converges into the thoracic duct. These thoracic and right lymphatic ducts exit the lymph fluid into the venous angles: left subclavian vein and right subclavian vein, respectfully.[2]

Nerves

The nerve supply to the lung arises from both the phrenic nerve and the pulmonary plexus. The phrenic nerve originates from the neck on third through fifth cervical nerves and travels down between the lung (anterior to the root of the lung) and heart until reaching the diaphragm. Thus, it innervates the fibrous pericardium, the central part of the mediastinal and diaphragmatic pleurae, and the diaphragm for motor and sensory functions.[3]

The pulmonary plexus arises from the vagus nerve (cranial nerve X). It divides into the anterior pulmonary plexus (lies anteriorly to the lung root) and the posterior pulmonary plexus (lies behind the root of the lung). The plexus is considered an extension of the fibers of the cardiac plexus, which travels with the pulmonary arteries into the lungs. Specifically, the plexus networks have parasympathetic, sympathetic, and visceral afferent fibers.[3]

The parasympathetic fibers that travel to the pulmonary plexus are composed of the presynaptic fibers of CN X. These fibers are the motor input to the bronchial tree's smooth muscle (results in bronchoconstriction), are inhibitory to the pulmonary vessels causing them to vasodilate, and finally are secretomotor by causing the bronchial tree glands to increase secretions. The sympathetic fibers of the pulmonary plexus are postsynaptic fibers whose cell bodies are in the paravertebral sympathetic ganglia of sympathetic trunks. These sympathetic fibers are bronchodilators by inhibiting the bronchial muscles, vasoconstrictors, and inhibit the bronchial tree's alveolar glands. Lastly, the visceral afferent fibers of the pulmonary plexus can conduct reflexes along the parasympathetic fibers that control function (reflexive) or can conduct painful stimuli (nociceptive), which accompanies the sympathetic fibers through the sympathetic trunk.

It is essential to point out that the nerves of the parietal pleura derive from the intercostal and phrenic nerves. Intercostal nerves also innervate the costal pleura and the peripheral diaphragmatic pleura.[6]

Muscles

The bronchi of the lungs contain smooth muscle that contract or dilate to control the narrowing of bronchial airways. Specifically, the bronchioles rely on smooth muscle and elastic fibers to maintain their wall integrity.[3] These smooth muscles also secrete inflammatory mediators, thus responsible for bronchial inflammation.[7]

It is essential to understand that the lungs do not have muscles to expand and contract during respiration. Instead, they rely on external muscles for respiration. The muscles activated during inspiration are the diaphragm (most important), intercostal muscles, sternocleidomastoid, levator costarum, serratus anterior, scalenus, pectoralis major and minor, and finally the serratus posterior superior muscles. The muscles of expiration, which aid the lungs to expel air, involves the muscles of the anterior abdominal wall, internal intercostal muscles, and serratus posterior inferior muscles.[8]

Physiologic Variants

Anomalies during lung development cause anatomic and physiologic variations of the bronchi. Examples are the growth of an abnormal amount of lung buds (classified as supernumerary) or the lung buds sprout from atypical sites (classified as displaced or ectopic). These anomalies fall into several categories; anomalies of bronchi arising from standard bronchial divisions, anomalies of bronchi arising from nonstandard airway locations, bronchial variation associated with abnormalities in situ, and finally miscellaneous abnormalities. The tracheobronchial anatomy can also change with age. Tracheobronchial variations (TBVs) are clinically rare but may be found during bronchoscopy or bronchography.[9][10][11]

Firstly, examples of anomalies of bronchi arising from standard bronchial divisions are accessory superior segmental bronchus and an axillary bronchus. An accessory superior segmental bronchus is when two bronchi are closely spaced and bridge the normal opening of the superior segmental bronchus. An axillary bronchus is a subsegmental bronchus, which arises as a segmental branch.

Secondly, examples of anomalies of bronchi arising from nonstandard airway locations are tracheal bronchus and accessory cardiac bronchus. The tracheal bronchus, also known as pig bronchus, is a divergent additional tracheal outgrowth; it is when a bronchus arises above the carina (usually affects the right lung).[12] The accessory cardiac bronchus is a rare anomaly prevalent in males. This deviant bronchus arises from the medial wall of the bronchus intermedius and travels medially and caudally towards the mediastinum. This variant can either be working, with branches that supply oxygen to the lung parenchyma or have a short blind-ending bronchial stump with no branches.

Thirdly, an example of bronchial variation associated with abnormalities in situ is in situs inversus, where there is a reversal of the normal right and left bronchial anatomy. Situs inversus can be isolated or in association with bronchiectasis (Kartagener’s syndrome). Another example is bronchial isomerism. Left isomerism is when the mirror image of the structures on the left lung is also on the right lung. Thus, the individual shows bilobed lungs bilaterally, each with a long bronchus. Patients with right isomerism have trilobed lungs bilaterally and each with a short bronchus.[13]

Lastly, miscellaneous abnormalities of the tracheobronchial tree include variants that are unclassified by the categories mentioned. An example is lung hypoplasia, which affects the bronchi development. Also, a diverticulum of the right upper lobe bronchus is a TVA; it resembles a tracheal bronchus that prematurely stopped during growth.

Surgical Considerations

General considerations

When damage to the airways is severe, surgical procedures are a consideration. Examples of lesions are trauma, inflammatory stenosis, foreign body, bronchopleural fistula, and primary tumors or abscesses of the airways. Surgical interventions are recommended to preserve the normal function of the remaining healthy lung. Thus, knowledge of the anatomy of the bronchopulmonary segments is essential for precise diagnosis and surgical removal of ill segments. Understanding the relationship between bronchopulmonary segments and the bronchial tree is also crucial for treatment, drainage, and clearance techniques used in physical therapy. Different surgical techniques are bronchoplasty, carina reconstruction, and tracheoplasty.[14]

Bronchoplasty

Bronchoplasty is the repair of the bronchus to restore the lumen's integrity. Timely bronchoplasty for tumors and stenosis promotes the preservation of pulmonary parenchyma. The most commonly performed bronchoplastic procedure is a sleeve lobectomy (also known as sleeve resection). A sleeve lobectomy is when the area of a damaged lobe is removed, along with part of its mainstem bronchus. The free ends of the bronchus are then reattached, and any remaining healthy lobes rejoined to the bronchus.[15][16]

Carina reconstruction

Carina reconstructions are rare but may be essential in surgical tumor removal of the trachea. The tracheal carina is a ridge of cartilage that divides the two main bronchi of the lungs. It can be reconstructed by the anastomosis of the right upper lobe bronchus to the left main bronchus. Carina reconstruction can involve lobectomy, pulmonary resection, or pneumonectomy.[17]

Tracheoplasty

Tracheoplasty (slide tracheoplasty) is used during laryngotracheal reconstruction. It is the surgical solution for primary tumors of the trachea and esophagus, tracheomalacia, laryngotracheal stenosis, or subglottic stenosis. Its purpose is to improve airflow in an obstructed airway. Surgical approaches depend on the location of the tracheal lesion(s) and the extent of the resection necessary. In the upper trachea, U-shaped resection or large cervical wedge resection is the recommendation. In the middle of the trachea, a median sternotomy is used. On the lower trachea, the procedure would be a median sternotomy or right thoracotomy.[15]

Nerve block considerations

Perioperatively for a wide range of surgical procedures, brachial plexus nerve blocks can be performed to optimize postoperative pain control following surgical procedures.[18] Common procedures utilizing these blocks to optimize postoperative pain control include, but are not limited to:

- arthroscopic shoulder procedures (including rotator cuff repair,[19][20] proximal long head biceps tendon (LHBT) procedures,[21][22] and distal clavicle excisions)

- shoulder arthroplasty

- open versus arthroscopic shoulder instability procedures (e.g., Latarjet procedures)

- tendon repair/reconstruction[23] (e.g. pectoralis major tendon repairs)

- fracture fixation procedures about the shoulder girdle (e.g., ORIF proximal humerus, ORIF clavicle[24][25][26])

Pre-existing COPD and other related pulmonary conditions serve as a contraindication to interscalene, superior trunk, and supraclavicular nerve blocks given the risk of iatrogenic injury to the phrenic nerve.[18]

Even in the setting of normal pulmonary function, patients should be informed of the risk regarding transient and even sometimes long-term/persistent hemidiaphragmatic paresis following interscalene blocks. The phrenic nerve originates from the neck on third through fifth cervical nerves and travels down between the lung (anterior to the root of the lung) and heart until reaching the diaphragm. Thus, it innervates the fibrous pericardium, the central part of the mediastinal and diaphragmatic pleurae, and the diaphragm for motor and sensory functions.

Several case reports exist in the literature have highlighted the potential for phrenic nerve palsy following ultrasound-guided interscalene nerve blocks/catheter placements. The incidence range varies from 2% to 5% for any postoperative neural injury following brachial plexus blockade.[27]

The proximity of the phrenic nerve to the brachial plexus in combination with its frequent anatomical variation can lead to unintentional mechanical trauma, intraneural injection, or chemical injury during these procedures.[28]

Clinical Significance

Aspiration of Foreign Bodies

The right lung is more commonly affected by inhaled foreign bodies. The right main bronchus has a wider diameter, is shorter in length, and lies more vertically relative to the hilum when compared to the left main bronchus; this is clinically important since aspirated foreign objects are more likely to settle in the right bronchus. While lying supine, the foreign body usually enters the right lower lobe (superior portion). While lying on the right side, the foreign body usually enters the right upper lobe. While upright, the foreign object usually enters the right lower lobe (lower portion).[29]

Lung Damage from Smoking

Phagocytes are cells within the lymph nodes that are capable of engulfing carbon particles from inspired air. In people who inhale excess carbon particles, such as those who live in cities or are chronic smokers, the particles stain the surface of the lungs and lymph nodes a mottled gray to black color.[30]

Bronchogenic Carcinoma

This condition is a common type of lung cancer that arises from the epithelium of the bronchial tree. Smoking is the highest risk factor for lung cancer. Due to the extensive lymphatics in the lungs, metastasis of bronchogenic carcinoma is wide and profuse. Due to the extensive pulmonary and bronchial vasculature, the tumor cells can easily invade the systemic circulation and metastasize to other organs.[31][32]

Non-Small Cell Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Associated with a higher risk in male smokers. Cancer that arises from bronchus, causing a central hilar mass. The patient presents with coughing, hemoptysis, bronchial obstruction, and wheezing. Patients can be hypercalcemic.[30][32]

Atelectasis

Atelectasis is the collapse of a lung due to the obstruction of the airways, which is otherwise normal. This non-aerated region of the lung parenchyma can also be blocked by shallow breathing due to anesthesia or prolonged bed rest. Atelectasis may have three causes: airway obstruction (mucus plug, foreign body, tumor); compression of parenchyma by extrathoracic, intrathoracic, chest wall processes; and increased surface tension in bronchioli and alveoli. Signs and symptoms are chest pain, cough, and breathing difficulty.[33][29][34]

Bronchopleural Fistula

In this condition, there is abnormal communication (passageway) between the bronchial tree and the pleural cavity. It can occur from trauma, post-operation, infection, or cancer. During a bronchopleural fistula, inspired air in the lungs can travel through the airway and enter the pleural space. They are very challenging to manage and correlate with high morbidity and mortality.[35][36]

Obstructive Lung Diseases

Obstructive lung disease is a respiratory disease category characterized by airway obstruction, thus trapping air in the lungs. Chronic episodes of obstruction to airflow can cause hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction and can lead to cor pulmonale.[37] Examples of obstructive lung disease are asthma (reversible bronchoconstriction) and bronchiectasis (chronic necrotizing infection of bronchi or obstruction that results in permanently dilated airways).[38][39] Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) includes chronic bronchitis (hypertrophy and hyperplasia of mucus-secreting glands in bronchi) and emphysema (tissue destruction in alveoli highly associated with smoking and an alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency).[40][41][42] Clinical presentations among patients usually include coughing, crackles, wheezing, cyanosis, dyspnea, digital clubbing.