Continuing Education Activity

The use of forceps in infant delivery has fallen out of favor among obstetricians in the past three decades. Forceps deliveries now make up about only 1.1% of vaginal deliveries (according to a retrospective cohort involving more than 22 million vaginal deliveries from 2005-2013). The use of vacuum extraction has also declined but is more frequently used compared to forceps delivery; this may be because vacuum extraction is easier to use in comparison to forceps. However, vacuum use is less likely to result in a successful vaginal delivery when compared to the use of forceps. This activity describes the indications, contraindications and complications of forceps delivery and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the management of patients in labor and improve outcomes.

Objectives:

- Describe the indications for forceps delivery.

- Review the complications of forceps delivery.

- Summarize the contraindications for forceps delivery.

- Outline the importance of collaboration and coordination among the interprofessional team to recognize the indications for forceps delivery, ensuring patient safety and improving outcomes.

Introduction

The use of forceps in infant delivery has fallen out of favor among obstetricians in the past three decades. Forceps deliveries now make up about only 1.1% of vaginal deliveries (according to a retrospective cohort involving more than 22 million vaginal deliveries from 2005-2013).[1] The use of vacuum extraction has also declined but is more frequently used compared to forceps delivery; this may be because vacuum extraction is easier to use in comparison to forceps. However, vacuum use is less likely to result in a successful vaginal delivery when compared to the use of forceps.[2] Despite the increased efficacy compared to the vacuum, forceps use is still on the decline. Some speculate that this downward trend is due to fear of litigation related to common complications of forceps delivery, including increased risk of perineal laceration and injury to the newborn. Others attribute the decreased use of forceps to lack of adequate resident training.[3]

Nonetheless, operative vaginal delivery with forceps has its benefits. When applied properly during the second stage of labor arrest, it has the potential to eliminate the need for a cesarean section. Cesarean section is a more invasive procedure with an increased risk of complications, and when compared to operative forceps delivery. Cesarean delivery has correlations with an increased risk of postpartum infection.[4][5] Cesarean sections also correlate with long term complications including increased risk of repeat cesarean section, placental abnormalities, and uterine rupture.[6] Preventing these complications is beneficial to patients which is why many providers support the revival of operative vaginal delivery.

Anatomy and Physiology

Understanding the anatomy of the female pelvis is important when using forceps because once applied inside the pelvis, the provider has limited visibility. Successful delivery primarily relies on maternal pelvimetry.

One of the requirements for performing a delivery with forceps is ruling out cephalopelvic disproportion; this requires knowledge of pelvimetry, which divides into four major types of pelvic categories:

- Anthropoid

- Android

- Gynaecoid

- Platypelloid

The most common is the gynaecoid pelvis. Gynaecoid and anthropoid are considered to be favorable for vaginal delivery, while android and platypelloid are not.[7] Most clinicians are not experienced or taught to determine the type of pelvis from a clinical exam. If necessary, they may determine the type through x-ray pelvimetry. Although no longer common practice, the obstetrical conjugate can also be used to determine if the maternal pelvis has adequate dimensions for successful vaginal delivery. The diameter between the ischial spines should be at least 10 cm. This dimension is known as the pelvic inlet as is best measured before the onset of labor.

Knowledge of fetal anatomy plays a role in determining fetal station and position. The fetal station is determined by palpating the fetal head and using the bipyramidal distance as a landmark to assess fetal position in reference to the ischial spines. The ischial spines determine zero station and a fetal head palpated above the ischial spines is considered a "negative" position. Conversely, a fetal head below the ischial spines is considered a positive station. The birth canal can be divided into thirds above and below the ischial spines, resulting in a numerical system using values -3 to +3. Another numbering system involves using centimeters to measure fetal station and consists of values from -5 to +5.[8]

Determining the fetal position should be at the same time as the fetal station, which allows the provider to prepare for additional maneuvering if the fetus is not in the occiput anterior position. A "diamond" shaped suture marks the anterior aspect of the fetal skull. If the fetus is in the occiput anterior position, this suture will be palpable on the posterior aspect of the maternal pelvis. Any position other than occiput anterior may make it more difficult for operative vaginal delivery since the rotation of the vertex may be necessary to deliver.

Indications

There are both maternal and fetal indications for operative vaginal delivery, which includes the use of forceps and vacuum extraction alike. No indication is absolute. The fetal indication is commonly a non-reassuring tracing when the vertex is well below the ischial spines which may preclude a cesarean delivery. Maternal indications include maternal exhaustion and prolonged second stage of labor (nulliparous: 4 hours with regional anesthesia and 3 hours without, multiparous: 3 hours with regional anesthesia and 2 hours without). Both imply adequate maternal pushing efforts with contractions.) According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the following criteria are necessary before proceeding with either vacuum or forceps delivery.[9]

- Cervix fully dilated

- Rupture of membranes

- Fetal head engaged (vertex presentation)

- Knowledge of the fetal position

- Fetal weight has been estimated

- Maternal pelvis adequate for vaginal delivery

- Anesthesia administered

- The maternal bladder is empty

- Maternal consent obtained, risks and benefits thoroughly explained

- A back-up plan if the operative delivery method fails

- Maternal cardiac or neurologic disease when maternal pushing is not feasible

Contraindications

Absolute maternal contraindications for operative vaginal delivery include the following:

- Cervix not fully dilated

- Membranes intact

- Fetal head not engaged

- Unknown fetal position

- Cephalopelvic disproportion

Relative maternal contraindications include malpresentation (unless planned breech extraction) and connective tissue disorders

Absolute fetal contraindications include the presence of a bleeding disorder (hemophilia, thrombocytopenia, von Willebrand disease) or bone demineralization (osteogenesis imperfecta)

Relative fetal contraindications include prematurity and macrosomia. There is no consensus on the minimum or maximum estimated fetal weight for forceps delivery.[9]

Equipment

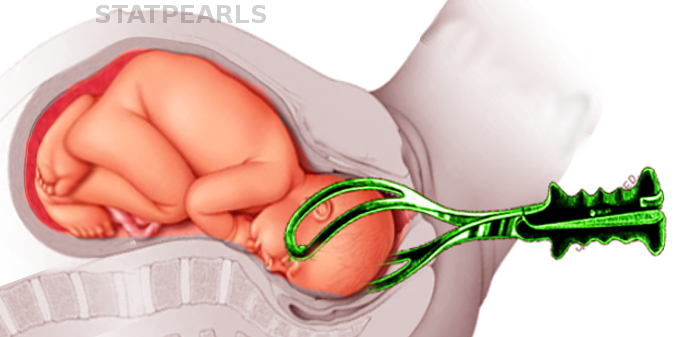

Forcep blades may be either smooth or fenestrated. Examples of fenestrated blades include Simpson and Elliot forceps. These types of forceps have crossed branches. The Simpson forceps have parallel separated shanks and are used with a long molded head. The Elliot forceps have overlapping shanks and are used with an unmolded head. The Tucker McLane blade is an example of forceps with a smooth blade without fenestrations. It is useful when delivering an infant with a round head.

All forceps are composed of four necessary components: a handle, lock, shank, and blade. The blade has a cephalic curve to accommodate the fetal head and a pelvic curve to accommodate the shape of the pelvis.

Simpson, Elliot, and Tucker McLane forceps all contain an English lock, which does not allow for full rotation. Keilland forceps have a sliding lock and minimal pelvic curve which allows disengagement and full rotation. Rotational forceps, like the Keilland model, have higher rates of maternal complications ( vaginal lacerations, hemorrhage) and fetal complications (shoulder dystocia, head lacerations from blades).[10]

Piper forceps are preferred for the aftercoming head in breech deliveries since they have a longer shank with the pelvic curve to help protect the head in a flexed position.

Personnel

A successful operative vaginal delivery requires a well-trained and experienced obstetrician. It may necessitate hundreds of deliveries with forceps to prevent or manage any maternal or fetal complications. A pediatrician should also be present at the time of delivery.

Preparation

The first step in preparing for a forceps delivery is to counsel and consent the patient, which includes explaining the risks and benefits of a forceps delivery as well as alternatives including vacuum-assisted delivery and cesarean section. It is also wise to consent for a cesarean section at the same time in case the forceps delivery is unsuccessful. The operating room team should also be alerted and be ready in case the emergency cesarean section is necessary particularly with a non-reassuring tracing.

The next step is to ensure the preferred forceps are readily available and in working order. Consider having a back-up instrument ready. The use of vacuum extraction after failed forceps delivery is not recommended due to a higher rate of fetal complications.[11] Additionally, because perineal and vaginal lacerations are a common complication of forceps delivery, instruments and sutures for laceration repair should also be set up on the obstetric operative table.

It is also vital in the preparation process to include the anesthesia and pediatric teams. Notify both teams ahead of time, so they have ample time to prepare for their role in the delivery process. Usually forceps delivery requires regional anesthesia such as epidural or pudendal block as well a local perineal since episiotomy, particularly right mediolateral, is common to allow for more space and fewer lacerations. Preparation for acid-base cord blood sampling should be included for all complicated deliveries.

Before forceps application, routine emptying of the bladder should take place which allows the fetal head to descend uninhibited. It is also helpful in case the forceps delivery fails, and an emergent cesarean section is necessary.

The use of prophylactic antibiotics is a debated topic. Based on limited evidence, their use does not significantly lower rates of maternal endometritis or maternal length of hospital stay.[12]

Technique or Treatment

Criteria-Forceps Delivery[9]

Outlet Forceps

- Scalp at introitus without separating labia

- Skull at pelvic floor

- Sagittal suture in AP diameter, ROA, LOA, OA

- Fetal head on the perineum

- Rotation less than 45 degrees

Low Forceps

- Skull greater than +2 station

- Rotation less than 45 degrees LOA or ROA to OA, LOP or ROP to OP

- Rotation greater than 45 degrees

Mid Forceps

- Above +2 station, head engaged

High Forceps- not classified

Forceps- Applications

- Sagittal suture equidistant between branches

- Posterior fontanelle one fingerbreadth above shanks

- Tips of blades lie over cheeks

- Fenestrated blades admit one finger between the heel of blade and head

- No maternal tissue grasped by forceps

The function of forceps is traction with minimal compression during contractions. Rotation, if necessary is done between contractions. Forceps are applied from below the fetal head while sitting. Traction force originates from the forearms, not the chest. The plane of traction is with the pelvic curve (Saxtorph-Pajot maneuver). Traction should be steady without rocking motion. An early episiotomy usually RML to avoid rectal injury is performed to allow for more space and prevention of vaginal lacerations. When the BPD passes the vulvar ring, remove the forceps in reverse order. Most cases progress with first or second pull and delivery with third or fourth pull.

Complications

Complications are difficult to ascertain due to the lack of studies with adequate control groups.

Maternal: perineal lacerations, vaginal lacerations, and hematomas, anal sphincter injury, long term complication of pelvic organ prolapse.[13]

Fetal: facial lacerations, facial nerve injury, ocular trauma, skull fracture, intracranial hemorrhage, subgaleal hematoma, hyperbilirubinemia, fetal death.[14]

Clinical Significance

Forceps allow for an alternative to vacuum-assisted delivery or cesarean section particularly with a non-reassuring tracing when delivery is imminent, maternal exhaustion from pushing, or medical comorbidities that preclude pushing or operative delivery. Advantages of forceps as compared to vacuum include:

- Unlikely to detach from head

- Can be used in premature fetuses

- Allows rotation

- Less bleeding from the scalp

- Less encephalopathy

In general, vacuum extraction is safer than forceps for the mother while forceps is safer than vacuum extraction for the fetus.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Operative delivery using forceps requires an interprofessional approach where medical professionals from different departments work together to achieve a successful vaginal delivery and the safe delivery of a healthy infant. This approach requires planning in order to coordinate readiness from all the departments involved. Institutions who practice the use of forceps deliveries must have systems in place that allow the smooth transition from a planned event during a complicated delivery to an emergent intervention yielding a positive result in either scenario.

Communication between medical professionals as well as simulation training is a key component of a successful forceps delivery. Each operative delivery whether vacuum or forceps must consider the risks, benefits, as well as alternatives for both mother and fetus for a successful outcome.