Introduction

The extrapyramidal system (EPS) is an anatomical concept first developed by Johann Prus in 1898 when he discovered that the disturbance in pyramidal tracts failed to prevent epileptic motor activity. Prus postulated that, apart from pyramidal tracts, there must be alternative pathways, called the "extrapyramidal tracts," that "delivered epileptic activity" from the cerebral cortex to the spinal cord.[1][2] Clinically, the term "extrapyramidal" was thus adopted to distinguish between the clinical effects produced by damage involving the basal ganglia and those of damage to the classic "pyramidal" pathway. Despite this distinction, however, the two systems have important anatomical and functional relationships.

The EPS serves an essential function in maintaining posture and regulating involuntary motor functions. In particular, the EPS provides:

- Postural tone adjustment

- Preparation of predisposing tonic attitudes for involuntary movements

- Performing movements that make voluntary movements more natural and correct

- Control of automatic modifications of tone and movements

- Control of the reflexes that accompany the responses to affective and attentive situations (reactions)

- Control of the movements that are originally voluntary but then become automatic through exercise and learning (e.g., in writing)

- Inhibition of involuntary movements (hyperkinesias), which are particularly evident in extrapyramidal diseases.

The EPS, therefore, controls the automatic activities but also influences voluntary motility through a tonic function. These regulation mechanisms involve the processing of centers located in multiple brain regions, such as parts of the cerebral cortex, the cerebellum, the thalamus, the reticular substance, and several basal ganglia. The term basal ganglia or basal nuclei refers to a group of subcortical nuclei. Among these nuclei, the caudate nucleus and the putamen nuclei, which together constitute the neostriatum, plus the substantia nigra (SN), red nucleus (RN), and the subthalamic nucleus of Luys compose the nuclei of the EPS. From all these centers, numerous subcortical tracts, or the extrapyramidal tracts, stem out and terminate in the spinal cord. However, the majority of tracts travel through the basal ganglia. Thus, anatomically, the EPS can be defined as a set of nuclei and fiber tracts that receive projections from the cerebral cortex and send projections to the brainstem and spinal cord and, functionally, works as a complex motor-modulation system.

Alterations affecting the various circuits play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of extrapyramidal motor disorders. Classic examples of injury to the EPS are Parkinson disease (PD), Huntington chorea (HC) caused by degenerative processes in the striatum, Sydenham chorea, multiple systemic atrophy (MSA), and progressive supranuclear palsy. In 1995, the World Health Organization's International Classification of Diseases released a classification for extrapyramidal and movement disorders. This chapter encompasses PD, secondary parkinsonism, other degenerative diseases of the basal ganglia, and several clinical conditions featuring dystonia, dyskinesia, and tremors (e.g., essential tremor). The clinical aspects of these clinical conditions are manifold and are not only the effect of alterations of voluntary movements. Because EPS probably establishes connections with the motor cortex by regulating the process of movement from the first ideational stages, voluntary movement can also become impaired in extrapyramidal pathology. For instance, slowing of voluntary movements such as walking is usually observed.

Moreover, the alterations that lead to these extrapyramidal pathologies mainly concern neurodegenerative processes. Thus, depending on the specific disease, the main symptoms are alterations of involuntary movements such as tremors, spasms, impairment of voluntary movements as well as a decline in cognitive functions involving mainly memory tasks, and affective sphere disorders such as depression. Postural alterations are also detected. For instance, the so-called Pisa syndrome, which is an abnormal posture in which the body appears to be leaning to one side like the Tower of Pisa, is an atypical feature of MSA. Finally, autonomic alterations and several non-motor symptoms, such as pain, can be part of the clinical picture of these pathologies.

Structure and Function

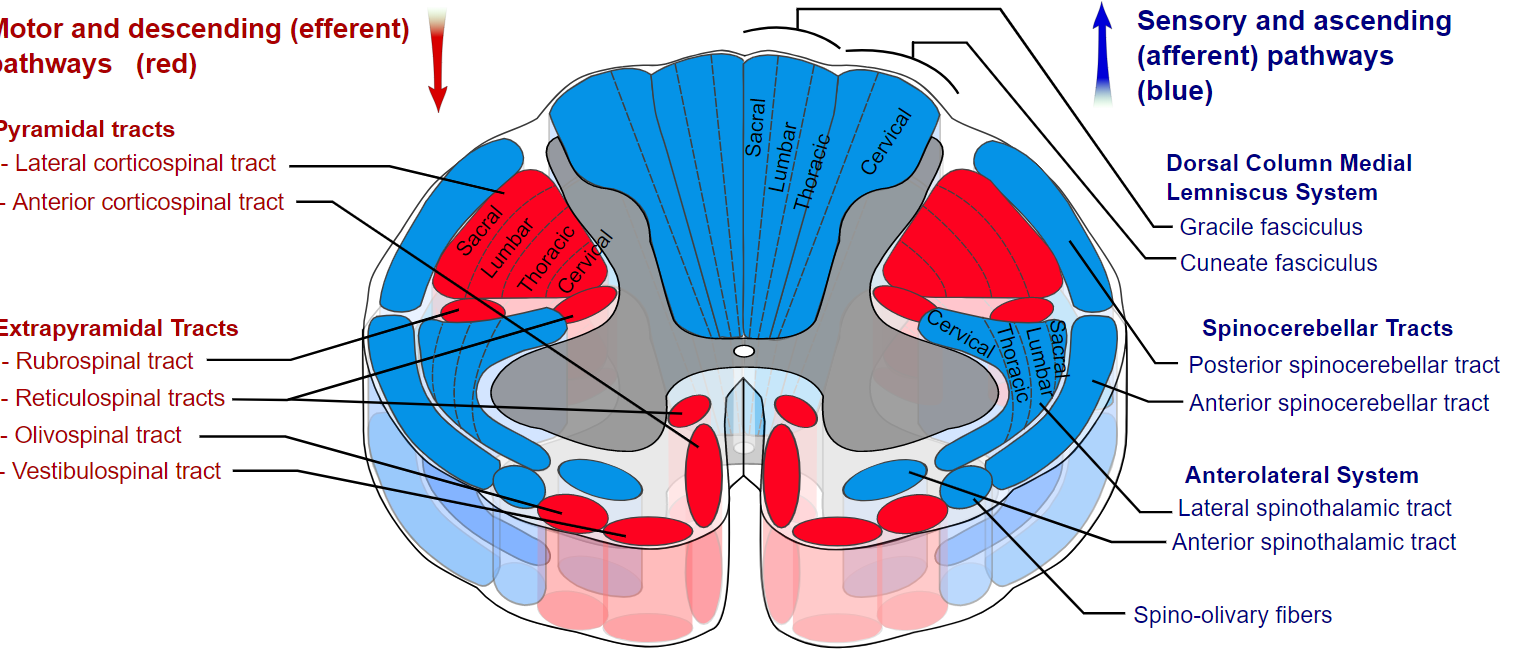

The EPS is polysynaptic in nature and composed of several tracts and nuclei. The tracts include the reticulospinal, vestibulospinal, rubrospinal, and tectospinal tracts.[3] See Illustration. Tracts of the Spinal Cord.

Reticulospinal Tract

This tract transmits motor commands from the reticular formation. The medial (pontine) reticulospinal tract originates in the pontine reticular formation and projects down to the ventromedial spinal cord via the ipsilateral anterior funiculus, which contains alpha and gamma motor neurons of the extensor muscles. The ascending spinothalamic tracts also stimulate the medial reticulospinal tract. The lateral (medullary) reticulospinal tract ordinates in the medullary reticular formation and projects to motor neurons in the spinal cord via the bilateral lateral funiculus.[4][5]

Vestibulospinal Tract

The medial vestibulospinal tract originates in the medial vestibular nuclei, or Schwalbe's nucleus, in the medulla and terminates in the limb motor neurons. They are responsible for innervating upper-body musculature, especially muscles of the neck and forelimbs. The lateral vestibulospinal tract originates in the lateral vestibular nuclei, or Deiter's nucleus of the pons, and ipsilaterally courses down to the Rexed's laminae VII and VIII. These laminae contain premotor interneurons and other alpha and gamma motor neurons that are responsible for innervating the extensor muscles that oppose gravity as well as inhibiting the flexor muscles. The vestibulospinal tract plays a crucial role in maintaining an erect posture.[6][7]

Rubrospinal tract

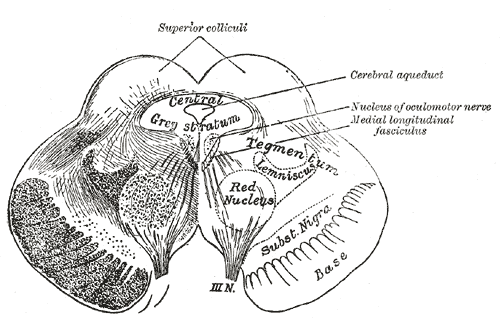

The rubrospinal tract originates from the red nucleus of the midbrain tegmentum. It crosses the midline in ventral tegmental decussation located in the caudal midbrain (see Image. The Midbrain or Mesencephalon). The tract forms a contralateral tract in the dorsolateral part of the lateral funiculus and lies in the ventrolateral part of the spinal cord. The rubrospinal tract mainly transmits signals into the red nucleus from the motor cortex and cerebellum to the spinal cord and ventral horn lamina V, VI, and VII.[8] In these laminae, the rubrospinal tract synapses with alpha and gamma motor neurons that stimulate the flexor muscles. The importance of the tract lies in the maintenance of muscle tone and in the regulation of rudimentary motor skills that are refined by corticospinal control.[9] With the corticospinal tract, the rubrospinal tract controls hand and finger movements in addition to flexor muscles.

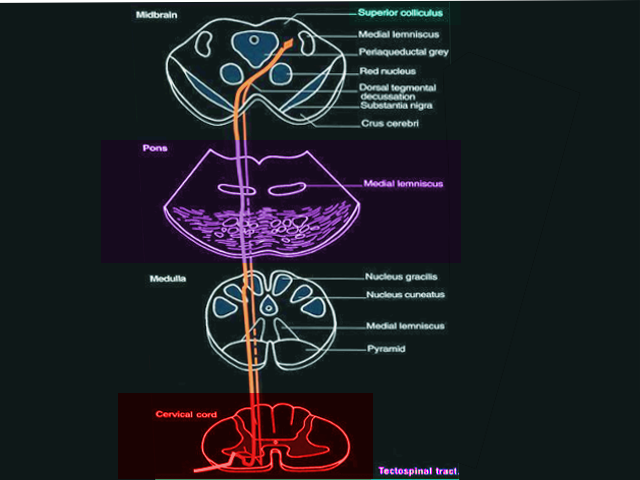

Tectospinal Tract

The tectospinal tract originates from the superior colliculus of the midbrain and receives stimulation from the retina and cortical visual association areas, courses ventromedial to the periaqueductal gray (PAG) matter, and terminates in the contralateral anterior gray horn lamina VI, VII, and VIII of cervical and upper thoracic segments of the spinal cord (see Illustration. Tectospinal Tract). It serves a critical function in the orientation of the head, neck, eyes, and upper extremities in response to sudden movement, loud noises, and bright lights.[10][11]

Embryology

The central nervous system (CNS) derives from a subspecialized ectoderm called the neuroectoderm. Over two to eight weeks of embryological development, notochord causes the evolution of the neural plate. The neural plate eventually differentiates into the neural tube via neurulation, which eventually forms the central nervous system. The brain forms from the cranial two-thirds, and the spinal cord forms from the caudal one-third of the neural tube.[12]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Blood Supply to the Brain

The main blood supply to the brain includes the internal carotid arteries (anterior circulation) and the vertebral arteries (posterior circulation). The internal carotid arteries arise at the bifurcation of the common carotid arteries and branch into the anterior and middle cerebral arteries. The anterior and middle cerebral arteries are the anterior circulation of the brain and contribute to the blood circulation of the forebrain. These blood supplies further branch into numerous arteries, such as the lenticulostriate arteries that pass through the white matter and deeper structures, such as basal ganglia and thalamus. The posterior circulation of the brain includes posterior cerebral, basilar, and vertebral arteries. The two vertebral arteries join at the level of the pons and form the basilar artery at the midline of the brainstem. The circle of Willis is the name given to the anastomosing vessels that connect the anterior and posterior circulation of the brain.

Blood Supply to the Spinal Cord

The main blood supplies to the spinal cord arise from the vertebral arteries, which originate from the subclavian artery, and from ten to twelve medullary arteries, which arise from the segmental branches of the aorta. The anterior spinal artery is responsible for vascular supply to the ventral portion of the spinal cord, and it originates from the vertebral artery at the level of the medulla. From the vertebral artery at the level of the medulla, medullary arteries form and combine to become the anterior spinal artery. The posterior spinal artery is responsible for supplying the dorsal portion of the spinal cord, and it originates from the vertebral artery as paired arteries that course along the posterior surface of the spinal cord.

The anterior spinal artery branches into multiple sulcal arteries that supply the ventral two-thirds of the spinal cord. The posterior spinal artery is responsible for supplying the majority of dorsal horns and dorsal columns. The anastomosing arteries that connect the anterior and posterior spinal arteries are called the vasocorona. The vasocorona supplies the white matter in a ring-like fashion by surrounding the spinal cord peripherally.

Clinical Significance

A large number of causes can induce syndromes and clinical manifestations of extrapyramidal damage. Most of the EPS alterations have a degenerative cause. A genetic component underlies some disorders, while injury processes, and those due to perfusive damage, are also possible. Extrapyramidal syndromes can also be associated with drugs such as antipsychotic drugs and reserpine, as well as toxic substances such as carbon monoxide, cyanide, and paraquat, 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP). Manganese can occupationally induce secondary parkinsonism through serious neurotoxicity involving the basal ganglia.[13][14]

General Clinical Features

The alterations of the extrapyramidal system can be grouped into hypokinesias and hyperkinesias.

Hypokinesias

Unlike pyramidal pathology, extrapyramidal involvement does not lead to paralysis but instead to scarcity or absence of movements which are termed hypokinesia and akinesia, respectively. Both conditions can express voluntary and involuntary movements. Several voluntary acts, such as walking, writing, and speaking, will slow down. Concerning involuntary movements, a reduction, or loss, of the associated movements of pendulation of the upper limbs during walking or mimic and expressive movements can be observed. Furthermore, slowness in the execution of voluntary movements, especially at the beginning of the movement or when this is about to complete, can be present. This condition is termed bradykinesia.

Hyperkinesias

These concern abnormal involuntary movements that can present in extrapyramidal diseases. These movements become distinguished by:

- Choreic movements: sudden, irregular, incomplete, aimless, variable movements

- Athetotic movements: arrhythmic, slow, exaggerated, tentacular movements

- Hemiballism: the movements are similar to choreic movements but much more intense and persist during sleep

- Rapid muscle contractions, which reproduce a stereotyped movement, repeated obsessively; they can become voluntarily inhibited, even if with effort

- Tremors: the extrapyramidal tremor (e.g., the typical tremor of PD) is rhythmic, at a slow pace (4 to 5 oscillations per second), not very wide, uniform, more pronounced at rest, and attenuates during voluntary and passive movements - for instance, it disappears during sleep

- Spasms: involuntary movements of a tonic type (intense and lasting contraction, but transient) or clonic (series of rhythmic contractions of short duration, separated by periods of rest)

- Myoclonus: rapid, sudden contractions involving isolated muscles or bundles of muscle fibers - usually do not cause motor effects

Among hyperkinesias, several discharge phenomena are also included:

- Spastic crying: it is frequently observable in people with pseudobulbar syndrome, where an insignificant cause can trigger spasmodic or spastic crying

- Forced gaze crisis: oculogyric tonic crisis, with a forced deviation of the eyes, sideways or upwards, lasting from a few minutes to a few hours, which repeats periodically, sometimes accompanied by simultaneous homologous rotation of the head

- Torsion spasm: deformation of the lordotic or kyphoscoliosis back-lumbar spine, with contortion movements

- Spastic stiff neck: rhythmic spasms of rotation and inclination of the body towards one side, sometimes accompanied by a lifting of the corresponding shoulder

In extrapyramidal diseases, signs and symptoms of a non-motor nature can occur. For example, disturbances of attention, slowed or monotonous ideation, and poor control of emotion and instincts are such findings.

Extrapyramidal Syndromes

Concerning the different associations between tone and movement disorders, two fundamental syndromes are distinguishable: pallidal syndrome and striated syndromes.

Pallidal syndrome

This syndrome is characterized by muscle hypertonia, bradykinesia, and sometimes by tremor (hypertonic-hypokinetic syndrome) and is mainly observed in PD. In particular, PD is characterized by generalized extrapyramidal hypertonia, static tremor, and akinesia. The hypertonia is mainly observed at the root of the limbs, is permanent, and is accompanied by an exaggeration of postural reflexes. For example, flexing the hand on the forearm remains for a few moments in this position before reverting. The static tremor predominates in the upper limbs; moreover, it is wide and regular. Akinesia is a loss of the ability to move muscles voluntarily. A typical sign of akinesia is 'freezing.' The patient loses automatic and associated movements, with difficulty regaining balance, and they walk with the center of gravity moved forward or in a stooped posture. Non-motor symptoms such as pain are usually essential features of the disease and can also precede motor disorders.[15][16]

Striated Syndromes

Also termed hyperkinetic-dystonic syndromes include the choreic syndrome characterized by choreic movements and hypotonia; the athetosis syndrome with athetosis movements and hypotonia; the hemiballism syndrome; and the hepatolenticular syndrome, better known as Wilson disease.

Bilateral Injuries At The Brainstem Level

In addition to quadriplegia, two fundamental pictures of hypertonia can be observed, depending on the level of injury: decerebrate rigidity and decorticate rigidity. The EPS plays a key role in both phenomena.

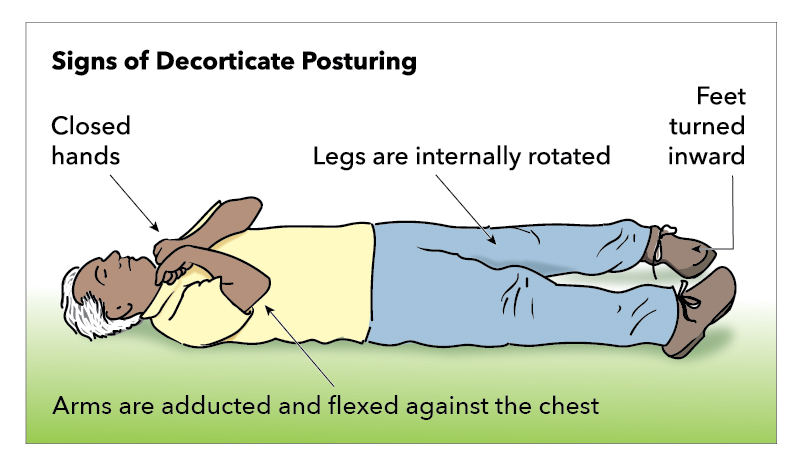

Decorticate Rigidity

Decorticate rigidity occurs when an injury at the superior border of the red nucleus disturbs descending corticospinal and rubrospinal tracts (see Illustration. Decorticate Posturing). This condition leads to the flexion of the upper extremities and extension of the lower extremities with painful stimuli.[17] The injury to the red nucleus causes subsequent overactivation of the rubrospinal tract and medullary reticulospinal tract. Also, the lateral corticospinal tract is disturbed, which causes flexor muscles of the lower extremities to be impaired and allows the pontine reticulospinal and medial and lateral vestibulospinal to induce biased extension.

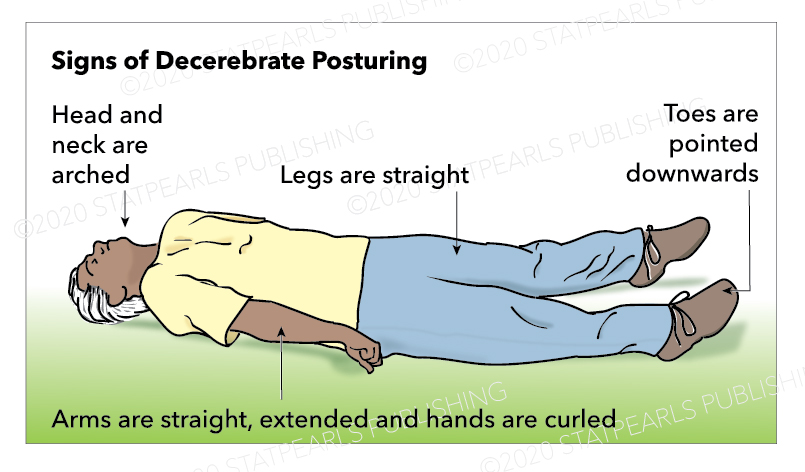

Decerebrate Rigidity

Decerebrate rigidity occurs when an injury at the superior border of the pons disconnects the posterior aspect of the brainstem and the spinal cord from the rest of the brain (see Illustration. Decerebrate Posturing). With the transection, stroke, or hemorrhage of the brainstem regions, the lateral ventrospinal tract and the reticulospinal tract over-activate extensor motor neurons with restricted inhibition of the cortex and basal ganglia. This, in turn, causes increased activity of alpha motor neurons and gamma motor neuron discharges.[7] As a result, the injury causes the extensor muscles of all limbs and muscles of the neck and trunk to have increased tone (i.e., the extension of elbows in addition to the extension and internal rotation of all extremities).