Continuing Education Activity

The definition of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is any degree of glucose intolerance with onset or first recognition during pregnancy. GDM can classify as A1GDM and A2GDM. The classification of gestational diabetes managed without medication and responsive to nutritional therapy is as diet-controlled gestational diabetes (GDM) or A1GDM. Conversely, gestational diabetes managed with medication to achieve adequate glycemic control classifies as A2GDM. Gestational diabetes is a disease developed during the second and third trimester of pregnancy, characterized by a marked insulin resistance secondary to placental hormonal release. This activity highlights the etiology, epidemiology, pathophysiology, treatment, complications, and prognosis for members of the interprofessional team that manage patients with gestational diabetes.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiology of gestational diabetes.

- Review the evaluation of gestational diabetes.

- Outline the treatment and management options available for gestational diabetes.

- Summarize the interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance gestational diabetes and improve outcomes.

Introduction

The definition of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is any degree of glucose intolerance with onset or first recognition during pregnancy. GDM can classify as A1GDM and A2GDM. Gestational diabetes managed without medication and responsive to nutritional therapy is diet-controlled gestational diabetes (GDM) or A1GDM. On the other side, gestational diabetes managed with medication to achieve adequate glycemic control is A2GDM.

Historically, the screening for gestational diabetes consisted of assessing patients history, past medical obstetric outcomes, and family history of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Even though it was useful, it was not appropriate. This screening method failed to identify approximately one-half of pregnant women with GDM. In 1973 a significant study suggested the use of the 50 g 1-hour oral glucose tolerance test as a screening for gestational diabetes; this is a very reliable method for screening, and it is used for approximately 95% of obstetricians in the united states of America as a method for screening GDM during pregnancy. In 2014, the U.S preventive service task force recommended screening all pregnant women for GDM at 24 weeks of gestation.[1][2][3][4]

Etiology

Gestational diabetes etiology is apparently related to 1) the pancreatic beta-cell dysfunction or the delayed response of the beta cells to the glycemic levels, and 2) the marked insulin resistance secondary to placental hormonal release. The human placental lactogen is the main hormone related to increased insulin resistance in GDM. Other hormones related to the development of this disease are growth hormone, prolactin, corticotropin-releasing hormone, and progesterone, these hormones contribute to the stimulation of insulin resistance and hyperglycemia in the pregnancy.

It has been reported some clinical risk factors for developing gestational diabetes. Those clinical factors include[3]:

- Increased body weight (a body mass index greater than 25)

- Decreased physical activity

- A first degree relative with diabetes mellitus

- Prior history of gestational diabetes or a newborn with macrosomia, metabolic comorbidities like hypertension

- Low HDL

- Triglycerides greater than 250

- Polycystic ovarian syndrome

- Hemoglobin A1C greater than 5.7

- Abnormal oral glucose tolerance test

- Any significant marker of insulin resistance (acanthosis nigricans)

- Past medical history of cardiovascular diseases

Epidemiology

Gestational diabetes affects around 2 to 10% of pregnancies in the United States of America.

Women with gestational diabetes (GDM) have an increased 35 to 60% risk of developing diabetes mellitus over 10 to 20 years after pregnancy.[3][4]

Pathophysiology

The human placental lactogen is a hormone released by the placenta during the pregnancy. It holds a comparable composition to growth hormone and induces important metabolic changes during pregnancy to support the maintenance of fetal nutritional status. This hormone is capable of provoking alterations and modifications in the insulin receptors. The following molecular variations appear to have links to diminishing glucose uptake at peripheral tissues:1) molecular alteration of the beta-subunit insulin receptor, 2) diminished phosphorylation of tyrosine kinase, 3) remodelings in the insulin receptor substrate-1 and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase.

Maternal high glucose levels cross the placenta and produce fetal hyperglycemia. The fetal pancreas gets stimulated in response to the hyperglycemia. Insulin anabolic properties induce fetal tissues to growth at an increased rate.[3]

There are reports that a higher body mass index and obesity can lead to low-grade inflammation. Chronic inflammation induces the synthesis of xanthurenic acid, which is associated with the development of pre-diabetes and gestational diabetes mellitus.[5]

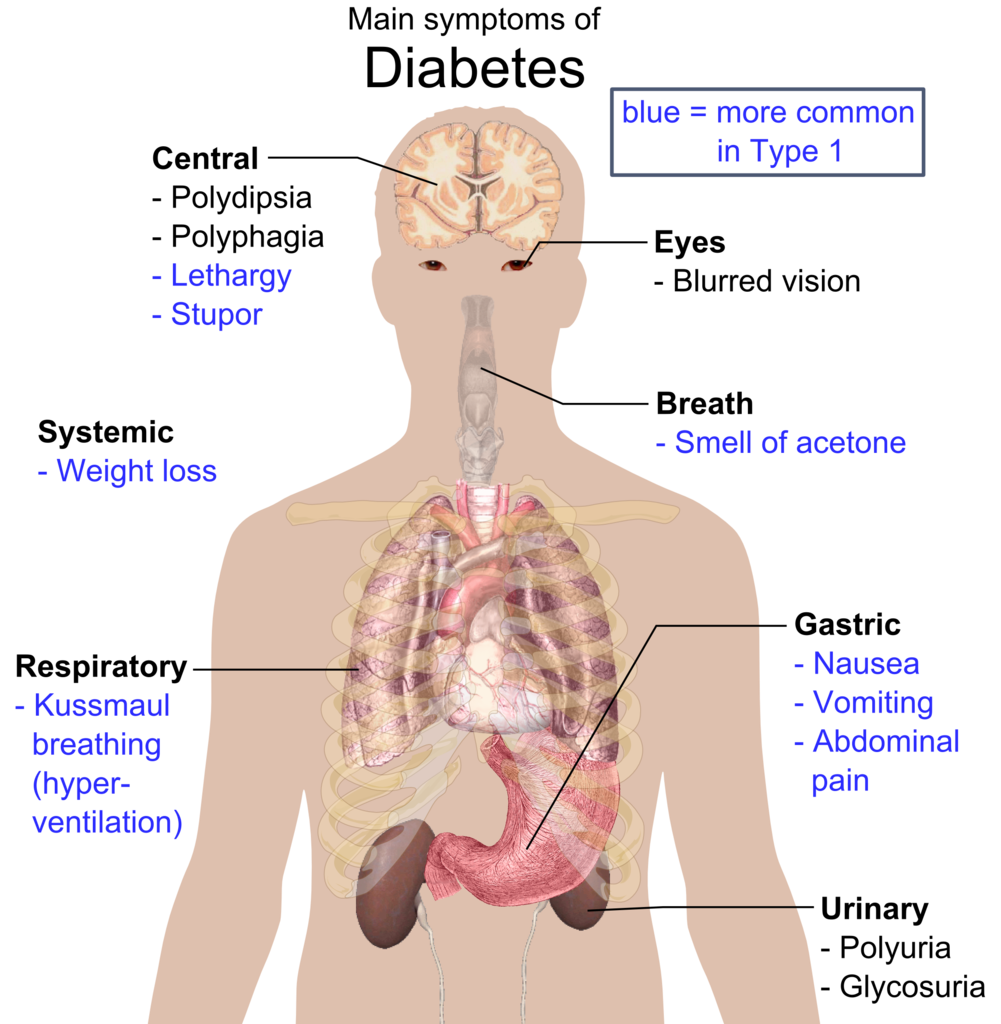

History and Physical

The past medical obstetric outcomes and family history of type 2 diabetes mellitus are important components of the history taking in GDM. The clinical features of gestational diabetes mellitus can be varied. The disproportionate weight gain, obesity, and elevated BMI can be suggestive features. The diagnosis is established by the laboratory screening method at the 24 to 28 weeks of pregnancy.

Reports exist that the gestational age when DSM develops influences pregnancy outcome.

Evaluation

Recommendations are for screening for gestational diabetes at 24 to 28 weeks of pregnancy with a 50-g, 1-hour oral glucose challenge test. If the values are abnormal, greater than or equal to 130 mg/dL (7.22 mmol/L), or greater than or equal to 140 mg/dL (7.77 mmol/L), a confirmatory test is necessary with a 100-g, 3-hour oral glucose tolerance test, with the following values: first hour over 180 mg/dL, second hour over 155 mg/dL, third hour more than 140 mg/dL. The presence of two or more abnormal results establishes the diagnosis of gestational diabetes.

The ADA recommends to consider screening strategy for detecting pregestational diabetes or early gestational diabetes mellitus in all women who are overweight or obese and have one or more of the following risk factors:

- Physical inactivity,

- First degree relative with diabetes

- High-risk race or ethnicity

- Have previously birthed an infant weighing 4000 grams or more

- Previously gestational diabetes, hypertension

- HDL level less than 35mg/dL

- Triglyceride level greater than 250 mg/dL

- Women with polycystic ovarian syndrome

- Hemoglobin A1c greater than 5.7%

- Impaired glucose tolerance test

- Impaired fasting glucose

- History of cardiovascular disease

- Other clinical conditions associated with insulin resistance

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) has noted that measurement of hemoglobin A1C is usable, but it may not be suitable to use alone, due to decreased sensitivity compared to oral glucose tolerance test.

The ACOG recommended levels of blood glucose in pregnancy is fasting plasma glucose under 95 mg/dL, 1 hour postprandial under 130-140 mg/dL, 2 hours postprandial below 120mg/dL.

In the postpartum period, 24 to 72 hours after the delivery, it is recommended to monitor glucose levels. After removing the placenta insulin resistance tends to improve, this can help escalate down insulin or hypoglycemic agents. Glycemic therapy will point towards achieving a euglycemic glucose level. At 4 to 12 weeks post-partum, it is recommended to perform a 75g oral glucose tolerance test to rule out the possibility of development of type 2 diabetes.[1][6][4][6]

Treatment / Management

Gestational diabetes management begins with nonpharmacologic measurements like diet modifications, exercise, and glucose monitoring. The ADA recommends nutritional counseling by a registered dietitian and development of a personalized plan based on the patients BMI. In some settings, in which dietitians are not able, the physician can provide recommendations based on the three major nutritional concepts: caloric allotment, caloric distribution, and carbohydrate intake.

The amount of exercise recommended in GDM is 30 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise at least five days a week or a minimum of 150 minutes per week.

If the patient glycemic control is not adequate despite optimal adherence to diet and exercise, it is recommended to begin pharmacologic treatment. The ADA first line of treatment for GDM is insulin. The therapy with insulin has been considered the standard therapy for gestational diabetes management when adequate glucose levels are unachievable with diet and exercise.

Insulin can help achieve an appropriate metabolic control, and it is added to the management if fasting blood glucose is greater or equal to 95 mg/dL, if 1-hour glucose level is greater or equal to 140 mg/dL, or if 2-hour glucose level is greater than 120 mg/dL.

The oral hypoglycemic agents, metformin and glyburide, are increasingly being used among women with gestational diabetes, despite the lack of FDA approval. Glyburide can initiate at a dose of 2.5 mg, and the maximum dose is 20mg. Metformin therapy should start at a dose of 500 mg, and the maximum dose is 2500 mg.

Basal insulin dose can be calculated using the patient’s weight formula, 0.2 units/kg/day. If the blood glucose level becomes elevated following a meal, rapid-acting insulin, or regular insulin can be prescribed before the meal, starting the dose with 2 to 4 units.

In the first trimester, the total daily insulin requirement is 0.7 units/kg/day, in the second trimester it is 0.8 units/kg/day, and in the third trimester, it is 0.9 to 1.0 units/kg/day.

The patient should divide the total daily dose of insulin into two halves; one half given as basal insulin at bedtime, and the other half divided between three meals and given as rapid-acting, or regular insulin before meals.

Lispro and aspart have approval for usage in pregnancy. The short-acting insulin is associated with less hypoglycemia.

The long-acting insulin detemir has received approval for the usage in pregnancy. Long-acting insulin causes less nocturnal hypoglycemia.[6][7][8][9][10][4]

Differential Diagnosis

Many women do not receive the appropriate screening for diabetes mellitus before pregnancy, so in some cases, it is challenging to distinguish gestational diabetes from preexisting diabetes.[7][9]

Prognosis

At 4 to 12 weeks post-partum, the recommendation is to perform a 75g oral glucose tolerance test to rule out the possibility of the development of type 2 diabetes, impaired fasting glucose or impaired glucose tolerance test.[11]

ADA and ACOG recommend repeating testing every 1 to 3 years for women who developed GDM and had normal postpartum screening results.[12][13]

Complications

The complications of developing gestational diabetes categorize as maternal and fetal. The fetal complications include macrosomia, neonatal hypoglycemia, polycythemia, shoulder dystocia, hyperbilirubinemia, neonatal respiratory distress syndrome, increased perinatal mortality, and hypocalcemia. Maternal complications include hypertension, preeclampsia, increased risk of developing diabetes mellitus, and increased risk of cesarean delivery.[12][13]

Consultations

OB/GYN physicians best manage gestational diabetes. However, it can include consultations with the endocrinology department to suggest recommendations for cases of hyperglycemia refractory to treatment.[14][13][14]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patient education is necessary. Education regarding appropriate diet changes, exercise, and lifestyle modifications can help to improve outcomes in patient with gestational diabetes.[14][13]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management and treatment of women with gestational diabetes is an emerging challenge for health care providers and teams. Thus, today, gestational diabetes requires an interprofessional team approach, including physicians, specialists, specialty-trained nurses, and pharmacists, all collaborating across disciplines to achieve optimal patient results and prevent further complications. Efforts and strategies are necessary to recognize them effectively. The development of prevention strategies would facilitate the treatment of gestational diabetes and would help improve health outcomes. Women with gestational diabetes have an increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes over 10 to 20 years after pregnancy.[14][13][11][4]

Many pregnant women who develop diabetes are not diagnosed until very late, which significantly increases the morbidity of the disease.

Many healthcare institutions are now operating pharmacy or nurse practitioner diabetic clinics that offer diabetic education to pregnant females. These clinics regularly monitor blood glucose and refer patients to an endocrinologist. This practice reduces the burden of the obstetrician, lowers healthcare costs, and helps the delivery of optimal care for those who need it.

All members of the interprofessional healthcare team need to collaborate and work together to manage gestational diabetes. Nursing stands at the forefront of patient encounters to determine adherence to therapeutic choices, and monitor for therapy efficacy as well as being alert for potential adverse effects, which they will communicate to other team members. Pharmacists need to perform medication reconciliation, verify the dosing of insulin or other antihyperglycemic drugs, and assist with patient counseling about medication and lifestyle adherence. In this cooperative paradigm, the interprofessional team can guide outcomes most successfully. [Level 5]