Continuing Education Activity

Scabies is a contagious skin condition caused by the mite Sarcoptes scabiei which burrows into the skin and causes severe itching. Scabies is transmitted by direct skin-to-skin contact or indirectly by contact with contaminated material (fomites). This condition is often challenging to diagnose as many patients may have only subtle symptoms. However, other patients may present with the classic history of exposure, severe pruritis that is worse at night, and reference to other individuals with similar symptoms. This activity reviews the evaluation and treatment of scabies and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in managing patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Describe the transmission of scabies.

- Explain how to make the diagnosis of scabies.

- Summarize strategies for preventing recurrence of scabies.

- Identify the importance of collaboration and communication among the interprofessional team members in assuring treatment of the entire family of a patient infected with scabies, which will prevent transmission and enhance outcomes for patients with this infection.

Introduction

Scabies is a contagious skin condition resulting from the infestation of a mite. The Sarcoptes scabiei mite burrows within the skin and causes severe itching. This itch is relentless, especially at night. Skin-to-skin contact transmits the infectious organism therefore, family members and skin contact relationships create the highest risk. Scabies was declared a neglected skin disease by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2009 and is a significant health concern in many developing countries. Infested individuals require identification and prompt treatment because a misdiagnosis can lead to outbreaks, morbidity, and an increased economic burden [1].

Etiology

The mite that causes scabies is Sarcoptes scabiei var. Hominis [2]. It is an arthropod belonging to the order Acarina. It belongs to the class Arachnida, order Astigmata, and family Sarcoptidae [3].

Clinically, it presents in three forms: classic, nodular, or a contagious crusted variant also called Norwegian scabies.

Sarcoptes scabiei resides in the dermal and epidermal layers of humans as well as animals. Scabies occurs worldwide and is a common skin condition. The infestation begins with the female mite burrowing within the stratum corneum of its host where it lays its eggs. It later develops into larvae, nymphs, and adults.

The classic form of scabies may have a population of mites on an individual that range between 10 to 15 organisms. It typically takes ten minutes of skin-to-skin contact for mites to transmit to another human host, in cases of classic scabies. Transmission of the disease can also occur by fomite transmission via clothing or bed sheets. This presentation of scabies often manifests with hyperkeratotic plaques that can be diffuse or localized to the palms, soles, and under fingernails.

The nodular form of scabies is a variant of the classic form. This form presents with erythematous nodules with a predilection towards the axilla and groin. The nodules are pruritic and considered to be a hypersensitivity reaction to the female mite.

The crusted variant, Norwegian scabies, can have up into millions of mites on a single individual. Crusted scabies occurs in patients who are immunocompromised due to immunosuppressive therapy, diabetes, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), or older age [4][5]. This high density requires only short contact with patients and contaminated materials for infection to occur. The immunological condition of the host and the extent of spread usually determines the number of infesting mites [4].

Epidemiology

The estimated worldwide prevalence of scabies is 300 million infected individuals each year [2][6]. It is a significant health concern in many developing countries and was declared a neglected skin disease by the World Health Organization in 2009 [6].

Scabies is highly prevalent in the following geographic regions: Africa, South America, Australia, and Southeast Asia. The high prevalence correlates with poverty, poor nutritional status, homelessness, and inadequate hygiene [2].

It is more common among children and young adults. Cases in these countries are associated with significant morbidity due to complications and secondary infections. These may include abscesses, lymphadenopathy, and post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis.

Scabies outbreaks in industrialized countries may occur sporadically or as institutional outbreaks in schools, nursing homes, long-term acute care (LTAC) facilities, hospitals, prisons, retirement homes, and areas of overcrowding [2].

Pathophysiology

Adult female mites dig burrow tunnels 1 to 10 millimeters long within the superficial layers of the epidermis and lay 2 to 3 eggs daily. The mites die 30 to 60 days later, and the eggs hatch after approximately 2 to 3 weeks. It merits mentioning that not all treatment options can penetrate the eggs stored within the skin [2][7].

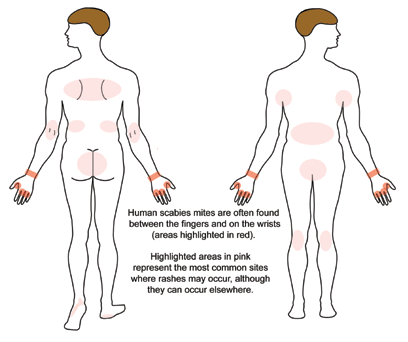

If an infestation occurs, papules may present within 2 to 5 weeks. These papules are tunnel or comma-shaped with length ranging from a few millimeters to 1 centimeter. Typically, infestations occur under thin skin in areas such as interdigital folds, areolae, navel region, and the shaft of the penis in men [2].

Histopathology

A punch biopsy is rarely needed to diagnose scabies. Scabies is often a clinical diagnosis. The biopsy usually will not obtain a mite, as there are often very few mites over the body (with the exception of crusted scabies ). The mite and the egg may be seen in the reticular dermis if you are lucky, along with an inflammatory infiltrate. The epidermis will often reveal significant scale and crust along with a serous exudate, neutrophils, and eosinophils

History and Physical

Examination findings include serpiginous white lines indicating mite burrowing. Common sites of mite burrowing include intertriginous areas, axillae, umbilicus, between digits, the beltline, nipples, buttocks, areolae of female breasts, flexural surfaces of the wrists or on the penile shaft. Type IV hypersensitivity reactions to the mite, eggs, or excrement may occur, forming erythematous papules. The itching associated with scabies gives way to scratching, encrustation, and possible impetiginization [6][4].

Secondary bacterial infections commonly occur following tunneling by the mites. Impetigo is especially common since a synergistic relationship between the scabies mite and Streptococcus pyogenes bacteria exists. Burrowing mites release complement inhibiting proteins that prevent the opsonization of S. pyogenes, which allows the bacteria to proliferate and evade the immune system [1].

Not all individuals exhibit classic manifestations of scabies infestations, which can make the infection challenging to diagnose. Patients may only have subtle signs and may not demonstrate the typical clues, which include a history of exposure, severe pruritis at night, or close contacts with a similar presentation [6]. Pruritis among several family members or close contacts should always cause the provider to think of scabies.

Evaluation

Scabies is classically diagnosed by visulization of the rash as well as patient history.

Scabies can be diagnosed by visualizing mites in skin scrapings in the stratum corneum [6][3]. This method often misses the correct diagnosis because of the high chance of sampling error.

Other methods, such as the non-invasive videodermatoscopy, can be utilized during the physical examination [2]. This technique has not yet become mainstream throught the Dermatology community. Videodermatoscopy uses a video camera connected to digital systems and equipped with optic fibers, lenses with up to 1000x magnification, and a light source or immersion liquid. This technique is not available in the vast majority of offices in the United States. Videodermatoscopy allows the inspection of the skin surface up to the superficial dermis and thus can identify burrows, mites, eggs, larvae, and feces. When compared to traditional skin scrapings, videodermatoscopy has several advantages. First, its noninvasive nature is better accepted by children, sensitive patients, and those who may refuse skin scrapings. It is also easy and quick to perform in comparison to the traditional microscope method. Moreover, the noninvasive technique minimizes the risk of accidental infections from blood-transmissible agents such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV). Videodermatoscopy also is useful in evaluating patients to follow up after completion of therapy, demonstrating the presence of viable mites in cases of persistent infection or unsuccessful treatment [2]. Videodermatoscopy is seldom used in clinical practice currently.

Dermoscopy, also called dermatoscopy, is similar to videodermatoscopy but is handheld and does not require connection to a computer. Dermoscopy is now commonly used in most Dermatology offices in the United States. Dermoscopy has a lens with up to 10x magnification. With a dermatoscope, it is possible to observe the burrow structure in scabies, also known as the "jetliner trail." The burrows are also poorly visualized in dark skin or hairy areas.

If the diagnosis is ambiguous, a skin biopsy can be used to confirm the diagnosis. In addition to biopsy, a newly developed serologic test can aid in the diagnosis of scabies [6]. Currently, this test is not commonly used in the United States.

Treatment / Management

There are various treatments available for scabies. Evidence shows that when medications are used as directed, the efficacy of standard treatment options is comparable. These include topical permethrin, topical crotamiton, and systemic ivermectin. Adverse reactions are rare to these medications [7].

Topical permethrin 5% cream is effective and widely used. The cream is typically applied once a week for two weeks (total of 2 treatments). However, this treatment is occasionally associated with scabies resistance, poor patient compliance, and rare allergic reactions [6].

Oral ivermectin is another option, although the United States Food and Drug Administration has not approved its use for scabies treatment. It is administered to individuals ten years and older and given one time. An additional dose is given two weeks later if symptoms persist. Two doses of ivermectin are scabistatic; the second treatment kills mites that have hatched since the first treatment. Oral ivermectin is recommended due to convenience, ease of administration, favorable side effect profile, and safety. Rates of compliance are higher with this treatment modality than with topical permethrin, and the tablet form of ivermectin reduces the likelihood of misuse or inadequate application, as may occur with the topical permethrin [6]. Systemic ivermectin is superior to topical permethrin when treating scabies outbreaks. Ensuring adequate treatment is especially pertinent to the treatment of individuals living in close proximity, such as in homeless shelters, prisons, and healthcare facilities [7].

Other options are topical lindane, 5% precipitated sulfur, malathion, and topical ivermectin.

Treatment choices may be limited in those with S. scabiei resistance or with limitations due to cost, availability, or potential toxicity, especially among pregnant women and children.

Treatment failure / recurrence is common, and isolating the cause can help prevent further infection and limit outbreaks in communities. Reasons for treatment failure include not treating close contacts simultaneously, not decontaminating beddings and clothes at the time of treatment, and nonadherence to the treatment regimen. Treatment failure of crusted scabies can result from ivermectin-resistant Sarcoptes mites. Moxidectin is the recommended therapy for known ivermectin-resistance [4].

Differential Diagnosis

The clinical presentation of scabies may resemble infections caused by other sources such as bacteria, fungi, parasites, and viruses [3]. Scabies often gets misdiagnosed as eczema, dermatitis prurigo nodularis, or lupus erythematosus [8].

Prognosis

Treating the patient along with close contacts and family members is associated with a good prognosis. With adequate treatment, patients can be expected to recover fully.

Without treatment, the infection can spread to other members of the community and cause an outbreak within the population.

Complications

Possible complications of a scabies infection include persistent itching, insomnia, secondary bacterial infection, and outbreaks of the disease to the community [6].

Deterrence and Patient Education

Scabies spreads quickly from person to person via regular skin contact or transmission via clothing or bed sheets. Management involves promptly treating infected persons and their close contacts and decontaminating bedding, towels, and clothing.

Isolation becomes crucial in crowded settings like hospitals, to stop the spread of infection. The bedding, towels, and clothing of the infected individual must be machine-washed in hot water (at least 75 degrees Celcius) and dried with hot air. Topical medication may be given to close contacts for prophylactic therapy [3][5].

Pearls and Other Issues

Treatment failure is common, and isolating the cause can help prevent further infection and limit outbreaks in communities.

Regardless of symptoms, all close contacts must receive treatment to prevent reinfection. Many states have legalized Expedited Partner Therapy, which allows physicians to write prescriptions for close contacts of a patient with scabies. This law applies if scabies is considered a sexually transmitted infection in that state. Patients and close contacts should also decontaminate beddings, towels, and clothing at the time that treatment is received [6].

Nonadherence to the treatment regimen is another cause of persistent infection. If topical permethrin cream is the chosen treatment option, it is to be applied to the entire body from the neck down in children and adults. In infants, the whole body, including the head, is treated with permethrin cream. The cream should be left on the body for 8 hours, rinsed off, and reapplied one week later. Permethrin is scabicidal, and the second treatment assures that any missed spots from the first treatment are covered in the second [6].

A common sequela that patients complain of is persistent itching after treatment, which may be attributable to treatment failure, misdiagnosis, or often cutaneous irritation. Other post-scabietic complaints include Id reaction also called auto-eczematization, and epidermal changes from topical treatments. Permethrin cream contains several potential allergens including formaldehyde, permethrin itself, and components of the cream base. Transient pruritis after treatment with oral ivermectin may occur and is due to the mass release of antigens following the destruction of the mites [6].

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Scabies is spread easily through skin to skin contact. Contact precautions and isolation of hospitalized individuals are vital to protecting healthcare workers and other patients in a healthcare facility [3]. Management of scabies requires an interprofessional team approach. If an interprofessional team member suspects an infection with Sarcoptes scabiei, they should alert other team members so that steps can be taken to prevent the spread.

Recognizing scabies infection and being able to diagnose this condition is crucial for patient care. One study showed that 45% of patients diagnosed with scabies, were actually suffering from other conditions such as eczema, papular dermatitis, irritant dermatitis, or contact dermatitis.

Education about scabies and its presentations is essential for all providers coordinating care, including primary care, emergency medicine, urgent care, pharmacy and even dermatology [6]. Pharmacists are aware of topical creams for scabies treatment and must be able to compound with other ingredients to effectively manage the infection and pruritis. Medication compliance should be encouraged because in most cases, failures are due to non-adherence to the treatment regimen. Nurses will likely be on the front-line for monitoring treatment adherence, providing further patient and family education, and determining other people who will need treatment. Finally, the nurse practitioner should educate the patient on how to eradicate scabies in the home; this is vital to ending the cycle of infestation.

Scabies is a significant problem in public health, and one common reason for treatment failure is non-adherence to the treatment regimen. Additionally, improvements in living conditions, avoidance of overcrowding, and avoidance of sharing personal care products can decrease the likelihood of persistence of this pest. While some individuals do obtain relief from symptoms, recurrences are frequent. The level of interprofessional collaboration outlined above is critical to treatment success and optimal outcomes. [Level 5]