Introduction

The elbow is a hinge joint comprised of bony and ligamentous stabilizers. Specifically, the elbow contains two collateral ligaments: the medial collateral ligament (MCL, also known as ulnar collateral ligament, or UCL) and the lateral collateral ligament (LCL). Each of these two ligaments is made up of smaller ligamentous portions. These structures provide stability for the elbow joint and constant tension through elbow motion. The constant tension and torque experienced by these ligaments leave them prone to injury, especially the MCL.[1]

Structure and Function

The elbow's ranges of motion (ROM) are flexion, extension, pronation, and supination. In healthy individuals, flexion lies between 130 to 154 degrees, extension from -6 to 11 degrees, pronation from 75 to 85 degrees, and supination from 80 to 104 degrees.[2]

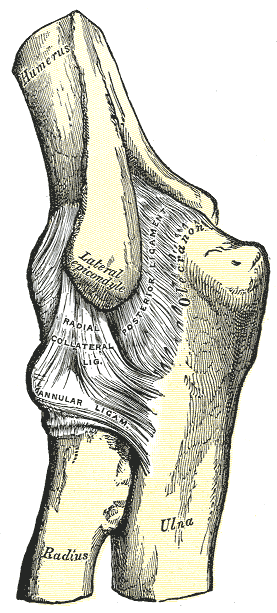

The bony anatomy of the elbow joint requires a brief description to lay the framework for the collateral ligaments of the elbow. Three bony structures create multiple articulations within the elbow complex. The three bony structures include the distal humerus, proximal radius, and proximal ulna. The distal humerus contains two main structures, the trochlea, and the capitellum. The medial epicondyle of the humerus provides a site of connection for ligamentous and muscular structures.

The proximal ulna also has two articulations, the greater and lesser sigmoid notches. The trochlea and greater sigmoid notch have 180 degrees of articular contact during the elbow range of motion (ROM). The lesser sigmoid notch articulates with the radius at the proximal radioulnar joint. The radial head and capitellum form the raidiocapitellar joint. The radial head allows for pronation and supination of the elbow.[1]

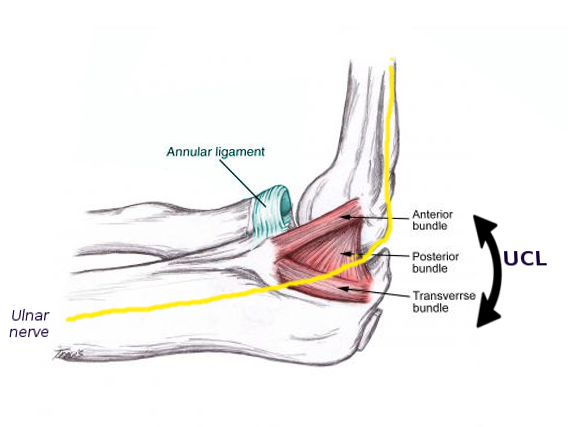

The MCL has three ligamentous portions: the anterior bundle (AMCL), the posterior bundle, and the transverse ligament (Cooper ligament). The AMCL and posterior bundle originate from the medial epicondyle of the distal humerus, on the posterior side of the elbow; this creates ligamentous tension with elbow flexion. The insertion site of the AMCL is the sublime tubercle on the coronoid process of the ulna, and the posterior bundle inserts on at the medial olecranon of the ulna.[1]

The transverse ligament originates from the olecranon process inserts on the sublime tubercle of the ulna.[3] As mentioned, the MCL acts as a primary stabilizer of the elbow, but specifically during valgus stress. For this reason, the MCL is the most commonly injured ligament in overhead throwing athletes; this is due to the mechanics of throwing motion that cause extreme valgus stress at high velocities. The anterior and posterior bundles provide reciprocal function, as the anterior portion is tight in extension, and the posterior portion is tight in flexion. During flexion of the elbow, the MCL also limits internal rotation.[4]

The MCL also functions as a restraint in posteromedial rotatory instability, specifically the AMCL. Further evaluating the MCL and the specifics of valgus stress, the MCL provides one-third of the valgus restraint in extension, and one half in 90 degrees of elbow flexion. The MCL coincides with the flexor and pronator forearm musculature in dynamic stability.[1]

The LCL contains four ligamentous portions: the lateral ulnar collateral ligament (LUCL), radial collateral ligament (RCL), annular ligament, and accessory collateral ligament. The LUCL and RCL originate from the inferior surface of the lateral epicondyle of the humerus. These two ligaments provide consistent tension through elbow ROM. The LUCL inserts at the proximal ulna and the RCL attached to the annular ligament. The annular ligament wraps around the radial head and attaches to the anterior snd posterior margins of the lesser sigmoid notch of the proximal ulna. The RCL and annular ligaments provide stabilization for the radial head.[1]

The accessory collateral ligament runs from the medial portion of the supinator crest (on the proximal ulna) and attaches to the inferior portion of the annular ligament.[5] The LCL functions to primarily resist posterolateral rotatory instability, and to a lesser extent, the LCL resists varus stress. The ulnohumeral joint provides the majority of stability when the elbow is under varus stress application; the LCL resists just 10% of varus stress. Within the LCL unit, the LUCL appears to be the primary stabilizer, but the entire four-ligament complex is required to provide radiohumeral, radioulnar, and ulnohumeral joint stability. The extensor forearm musculature coincides with the LCL ligament to provide stability with dynamic motion. the LCL is most vulnerable in the supinated position.[1]

Embryology

The elbow joint develops in three phases, the homogenous interzone, three-layered interzones, and cavitation. Chondrogenic areas are termed homogenous interzone around six weeks, and cartilaginous development increase via appositional growth. Homogenous zones convert into three-layered interzones at seven weeks. Mesenchymal tissue will condense into a fibrous capsule, and vascular mesenchyme becomes incorporated into the joint as synovial mesenchyme. This synovial mesenchyme will form the synovial tissue as well as the intracapsular ligaments. Cavitation, occurring at eight weeks, is when the articular cavity will form. Cavitation is initially independent of movement, but articular motion is necessary for full differentiation and development of the cavity.[6]

There is a discrepancy when the collateral ligaments are first visible. Studies have demonstrated visualization of the collateral ligaments in as early as 56 days in a 31 mm fetus. Yet other studies mention requiring fetuses of 270mm or larger for visualization of the collateral ligaments. Merida-Velasco et al. found that during week 12, vascular canals became apparent in the humerus, trochlear notch of the ulna, and radial head. It was at this time that the lateral ligaments began to develop into small densities of the outer aspect of the articular capsule.[6]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The elbow joint receives its blood supply from peri-articular anastomoses. Specifically, the brachial, deep brachial, ulnar, and radial arteries have collateral and recurrent branches to provide continuous blood flow. Superior collateral branches include superior collateral, inferior ulnar, and radial collateral arteries. The inferior collateral branches include the anterior and posterior ulnar recurrent arteries, the recurrent interosseous artery, and the radial recurrent artery. The venous outflow is provided by the radial, ulnar, basilic, and brachial veins.[7][8]

Specifically, the blood supply to the medial collateral ligament is unknown. A descriptive laboratory study utilizing 18 fresh-frozen male cadaveric elbows injected 60 mL of India ink into the brachial artery of each elbow. The proximal MCL consistently exhibited dense blood supply, while the distal MCL was hypovascular. The authors also found a possible contribution to the proximal MCL from the medial epicondyle. An artery from the flexor/pronator musculature also consistently provided blood to the proximal MCL. The average length of vascular penetration was 49% for the entire MCL. The study concluded there is a difference in vascular supply between the proximal and distal MCL. They suggested that the hypovascularity of the distal MCL may result in a lack of appropriate healing capacity, and MCL injuries may differ in a progression based on the location of the injury (proximal vs. distal).[9]

Superficial cubital lymph nodes and deep cubital lymph nodes are located above the medial epicondyle at the elbow. The superficial cubital nodes receive lymph from the medial side of the hand and forearm, while the deep cubital nodes drain the elbow joint itself. The lymph from these nodes eventually reaches the axillary lymph nodes bilaterally. The lymph from the left will enter the thoracic duct and lymph from the right will enter the right lymphatic duct.[7]

Nerves

The elbow joint receives branches of the median, radial, and musculocutaneous nerves anteriorly. Posteriorly the elbow joint is supplied by the ulnar nerve.[7] The median nerve branches into small sections that innervate the anteromedial epicondyle, where the MCL originates. The ulnar nerve supplies the posteromedial part of the elbow capsules, also in the neighborhood of the medial epicondyle and the olecranon. Branches from the radial nerve supply the posterolateral region of the elbow capsule, which is the location of the LCL.[10]

Muscles

The MCL works with the medial flexor musculature to resist valgus stress. Medial flexor musculature includes the flexor carpi ulnaris, flexor carpi radialis, flexor digitorum superficialis, and pronator teres. The LCL works with the extensor forearm musculature to resist varus forces. The extensor muscles include the extensor carpi ulnaris, extensor digitorum communis, extensor carpi radialis brevis and longus, and the anconeus. The anconeus is of significant importance because it provides major dynamic constraint to posterolateral rotatory instability and varus stresses, two functions that are also provided by the LCL.[1]

Physiologic Variants

A study examining cadaveric specimens looked at specific ligaments of the MCL (anterior bundle, posterior bundle, and transverse ligament). Specifically, they focused on the transverse ligament and its relationship with the anterior ligament. The majority of the transverse ligament continues to the distal half of the anterior ligament, and less common variants included transverse ligaments that traveled the entire anterior ligament.[3]

There is minimal variation with the anterior and posterior bundles. Of note, while the most common insertion site for the anterior bundle of the MCL is the sublime tubercle, variations have been found. Studies have found anterior bundle insertion only 1 mm away from the joint line. Other studies have found the insertion of the anterior bundle to be 3 mm more distal. This distal insertion has clinical relevance because it creates a small recess on arthrograms, which simulates a partial undersurface tear of the anterior bundle.[11]

An accessory or "extra bundle" ligament belonging to the MCL was also present in a quarter of examined specimens found in one study. The addition of this ligament creates an MCL comprised of four ligaments. The extra-bundle ligament originates from the posteromedial aspect of the capsule and inserts on the transverse bundle. The transverse bundle itself has a variation of a fanlike distribution with insertions onto the anterior bundle and coronoid; this creates a strong oblique pattern on imaging.[11]

Surgical Considerations

Posterolateral rotatory instability (PLRI) occurs secondary to a traumatic or iatrogenic injury to the LCL, which is the most common recurrent instability of the elbow. The radial head frequently subluxes, which creates lateral elbow pain and mechanical issues while the elbow is in flexion and supination, and a load is applied.[1]

While conservative treatment such as physical therapy and activity modification should be trialed, nonoperative management of PLRI is typically ineffective. Surgical treatment is necessary to restabilize the joint in patients with persistent and symptomatic instability that causes pain or functional impairment. In acute, simple dislocation, closed reduction under general anesthesia is suggested. If the lateral elbow is stable past 30 degrees of extension, the patient wears a dynamic brace for six weeks. However, if after the closed reduction, the lateral elbow is still unstable before 30 degrees extension, ligament repair is necessary.

Chronic and symptomatic PLRI requires surgical intervention, as mentioned. The pivot shift test is performed on a supine patient, with the forearm hypersupinated. Valgus stress, along with an axial load, is then applied to the elbow while moving the elbow form extension to flexion. A positive-shift test on a conscious patient is with patient apprehension. In a sedated patient (under general anesthesia), this test is positive with subluxation or dislocation of the elbow, typically occurring between 30 to 45 degrees of flexion.

Low-grade PLRI (subluxation) is treated with LCL imbrication via arthroscopic or open technique. Severe PLRI (dislocation) requires LCL reconstruction with graft use. Results after reconstruction show good to excellent results in 85% of patients. Recurrent instability has been seen even after surgical intervention, in up to as many of 25% of patients after medium to long-term follow-up.[12]

MCL injury is more common, and especially seen in overhead throwers such as pitchers. For painful, symptomatic MCL injuries, reconstruction is a reliable treatment method for correction. Surgery is indicated after nonoperative treatment has been exhausted. Surgical treatment for the MCL is one of the most well known in the sports world and is dubbed "Tommy John surgery" after pitcher Tommy John was successfully treated using the following technique. The docking technique is most commonly performed. Advantages include minimizing injury to the flexor/pronator musculature, avoidance of the ulnar nerve, providing an optimal location for graft tensioning, and minimizing the amount of bone removed from the medial epicondyle.[13]

Surgical treatment utilizes autograft, most commonly from the palmaris longus. Other graft options include gracilis, semitendinosus, toe extensor, plantaris, patellar tendon, and Achilles autografts. This injury that was once deemed a career-ending injury for major league baseball pitchers now shows an astounding 83% return to sport after UCL reconstruction.[14]

Clinical Significance

The collateral ligaments and their significant responsibility in maintaining elbow function make it pivotal for physicians to diagnose injuries properly. Whether the MCL or LCL injury at the elbow, a history, physical exam, imaging, and exhausted conservative treatments prior to surgery is the generalized outline of patient care.

Medial elbow injuries are amongst the most common in sports. Elbow injuries are the most common cause of time loss (over ten days) in collegiate pitchers, Upper extremity injuries account for 45% of all injuries in the NCAA, and 7-8% of these injuries belong to the elbow. Specifically pertaining to baseball, 97% of pitchers elbow pain is on the medial side of the elbow [14].

A patient history determining the location of the pain, how long the pain has been present, the exact point in motion where the patient experiences the injury is imperative in diagnosing MCL injury. If present in an athlete, they may complain of decreased performance, such as throwing velocity or stamina. Patients might also site issues of numbness and tingling in the ulnar distribution pattern since the chronic UCL injuries are associated with ulnar neuropathy. Physical exam should check for the palmaris longus muscle if surgery is required; this requires the patient to flex the wrist with opposing the first and fifth digits.

Special tests, including the valgus stress test, milking maneuver, and moving valgus stress test, can be performed to facilitate the diagnosis of UCL injury. Imaging such as MRI, MRA, and US provide the best visualization for the UCL. The MRA has the highest sensitivity and specificity, along with superior interobserver reliability. Imaging can also provide prognostic factors. One study demonstrated that MRI of UCL with a higher T2 signal intensity is less likely to benefit from conservative treatment.[14]

While not as common as MCL injuries, PLRI due to LCL damage can occur. Similar to that of MCL, history is a critical portion in evaluation, although injury to the LCL may not be as apparent as is with the MCL. The physical exam can include special tests, such as the pivot-shift test (mentioned above), posterolateral rotatory drawer test, chair push-up test, prone push-up test, and table-top relocation test. All of these are examining for radial head subluxation or apprehension in conscious patients.[1]

Varus posteromedial rotatory instability occurs when axial and valgus stress is applied to the forearm, which is in a pronated position. This stress results in a fracture to the anteromedial facet of the coronoid, and LCL rupture. This injury typically occurs in an acute, traumatic setting. In a subacute setting, the gravity-assisted varus stress test is an option, where the patient flexes and extends their elbow at 90 degrees of shoulder abduction, allowing gravity to apply the varus stress. This technique has shown to be the most sensitive and specific in diagnosing varus posteromedial rotatory instability.[1]

Other Issues

While UCL surgical intervention has progressed over the years, the tracking of patient outcomes in a quantitative manner is lacking relative to other musculoskeletal injuries such as ACL tears and its reconstruction. The function of the UCL and the stresses put on this ligament need to be analyzed in various settings, especially the athletic setting such as baseball. Functional screening and quantitative measures regarding injury progression, proper postsurgical therapy, and the timeline for return to sport still need to be accounted for in the literature regarding UCL injuries.[15]