Continuing Education Activity

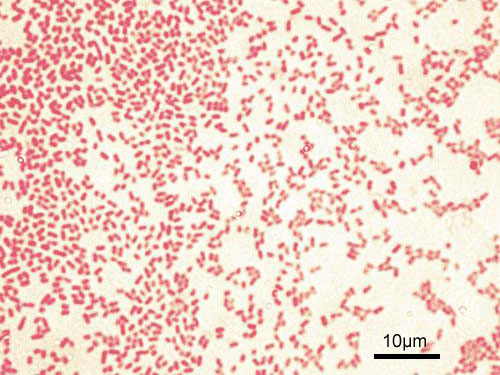

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a gram-negative, aerobic, non-spore forming rod that is capable of causing a variety of infections in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts. Its predilection to cause infections among immunocompromised hosts, extreme versatility, antibiotic resistance, and a wide range of dynamic defenses makes it an extremely challenging organism to treat in modern-day medicine. This activity outlines the epidemiology and management of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections.

Objectives:

- Outline the epidemiology of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections.

- Identify the wide array of infections that vary in severity caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

- Review the antimicrobial options available for Pseudomonas infections.

- Describe interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to multi-drug resistant Pseudomonas infections and improve outcomes.

Introduction

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a gram-negative, aerobic, non-spore forming rod that is capable of causing a variety of infections in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts.[1] Its predilection to cause infections among immunocompromised hosts, extreme versatility, antibiotic resistance, and a wide range of dynamic defenses makes it an extremely challenging organism to treat in modern-day medicine.[2]

Etiology

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is commonly found in the environment, particularly in freshwater. Reservoirs in urban communities include hot tubs, jacuzzis, and swimming pools. It can cause a wide array of community-acquired infections like folliculitis, puncture wounds leading to osteomyelitis, pneumonia, otitis externa, and many others. It is commonly an opportunistic pathogen and is also an important cause of nosocomial infections like ventilator-associated pneumonia, catheter-associated urinary tract infections, and others. Reservoirs in the hospital setting include potable water, taps, sinks, toothbrushes, icemakers, disinfecting solutions, sanitizers, soap bars, respiratory therapy equipment, endoscopes, and endoscope washers.[1][2]

Epidemiology

Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections are common in individuals with an immunocompromised state such as cystic fibrosis, bronchiectasis, neutropenia, burns, cancer, AIDS, organ transplant, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, and ICU admissions. Individuals with invasive devices e.g., indwelling catheters or endotracheal tubes, are also at risk due to the organism's unique ability to form biofilms that are difficult to detect.[2]

Pathophysiology

Pseudomonas aeruginosa possesses many mechanisms for antibiotic resistance and a variety of virulence factors that collectively account for the broad-spectrum of infections it causes and the increasingly challenging treatment for the resulting antimicrobial resistance. Multiple mechanisms have been identified for Pseudomonas antibiotic resistance, examples are intrinsic antibiotic resistance, efflux systems, and antibiotic-inactivating enzymes.[3] Intrinsic antibiotic resistance is the ability to restrict membrane permeability to antimicrobials. Efflux systems allow the bacterium to direct harmful or toxic compounds outside the cell membrane. Additionally, many isolates possess beta-lactamases and extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs). The ability of Pseudomonas bacteria to form a biofilm is also an important mechanism with which it can increase antibiotic resistance and resist host defenses.[2][3] This is especially important in cystic fibrosis patients, where most patients acquire the infection in the first year of life either from the environment or from healthcare facilities (inpatient or outpatient settings).

History and Physical

Pseudomonas aeruginosa causes a wide spectrum of infections with varying severity, examples include:

- Pseudomonas folliculitis is characterized by a maculopapular pruritic rash, axillary lymphadenopathy, breast tenderness, and fever. It is associated with the use of hot tubs, jacuzzis, and pools.[4]

- Puncture wounds in the foot, especially in children, can lead to infection with Pseudomonas. A classical scenario is a nail or glass injury through rubber shoes or soles. Local tenderness, purulent discharge, other signs of infection are found; however, delay in the presentation and diagnosis due to lack of symptoms initially may predispose to serious complications like osteomyelitis and septic arthritis.[5]

- In cystic fibrosis exacerbations, pseudomonal coverage is always needed. Chronic infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa occurs in more than 60% of adults with cystic fibrosis and is linked to higher mortality.[2][6]

- In patients with burns, Pseudomonas infections were found to decline and are replaced by gram-positive organisms and other emerging gram-negative organisms e.g., Aeromonas hydrophila.[7] In pseudomonal burn infections, a blue-green purulent discharge may be found, among other signs of local and systemic inflammation, and it may progress to sepsis and septic shock.

- Patients with diabetes are more likely to develop malignant otitis externa caused by Pseudomonas and present with otalgia and otorrhea. Examination frequently reveals granulation tissue inside the ear canal.[8]

- Populations at-risk are extremely susceptible to pneumonia caused by Pseudomonas. Pseudomonas pneumonia should be considered in any patient who has signs and symptoms of pneumonia and who is immunocompromised.[9]

- While patients with an organ transplant in general, are susceptible to all systemic pseudomonal infections, kidney transplant patients are at increased risk of recurrent pseudomonal urinary tract infections.[10]

- Other examples include endophthalmitis, endocarditis, meningitis, and many others.[11]

Evaluation

Lesion culture from patients with folliculitis after the use of hot tubs frequently grow Pseudomonas aeruginosa.[4] In puncture wounds and malignant otitis externa, clinicians should look for early signs of deep tissue involvement. Imaging may be needed to exclude soft tissue, bone, and joint involvement.[5] In systemic infections, routine laboratory and imaging workup are needed in addition to blood, urine, and tissue cultures if necessary. Due to the high prevalence of antibiotic resistance, the determination of sensitivity to different antimicrobials in pseudomonal infections is extremely important as they guide therapy.

Treatment / Management

Clinicians should consider pseudomonal infections in all at-risk patient groups and exert a high level of suspicion in severe infections leading to respiratory failure, septic shock, or any ICU admission. Hot tub folliculitis is generally self-limited, and no intervention is required, although antipseudomonal antibiotics may be needed.[4] In puncture wounds, in addition to regular staph and strep coverage, clinicians should consider pseudomonal coverage, especially if there are signs of deep infection.[5] Extended courses of IV antibiotics and surgical debridement may be needed.[8] In respiratory failure, pneumonia, sepsis, septic shock, and all systemic infections requiring an ICU admission, Pseudomonas infections should be considered upon presentation. The local antibiogram is extremely important to guide empiric therapy until sensitivity results are available. In addition to broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage, double pseudomonal coverage may be needed in cases of septic shock, respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation, ICU admissions, and the presence of one or more risk factors for multi-drug resistant organisms.[9] Some agents from multiple antibiotic groups have pseudomonal coverage. Carbapenems (e.g., meropenem), cephalosporins (e.g., ceftazidime, cefepime), aminoglycosides (e.g., gentamicin, tobramycin, and amikacin), and fluoroquinolones (e.g., ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin) are generally used as first-line therapy until culture and sensitivity results are available.

Differential Diagnosis

Hot tub folliculitis should be differentiated from other causes of rash and skin infections. Malignant otitis externa is often confused with other ear infections. Bone involvement leading to osteomyelitis in malignant otitis externa and pseudomonal puncture wounds may need more aggressive interventions for diagnosis e.g., tissue or bone biopsy to differentiate other causes of infection. In systemic infections, other organisms that can cause overwhelming infections and sepsis should always be considered. Broad coverage is needed initially until culture and sensitivity results are obtained.

Prognosis

Fortunately, some pseudomonal infections are self-limited e.g., hot tub folliculitis.[4] Others may be more challenging but still have good outcomes, as is the case with pseudomonal osteomyelitis secondary to puncture wounds. However, long-term radiographic evidence persists in those cases.[5] In cases of pneumonia requiring mechanical ventilation, septic shock, and burn infections, the prognosis varies and is largely dependant on the severity of the underlying disease process and the availability of antimicrobial agents that remain with pseudomonal activity.[11]

Complications

Osteomyelitis of foot bones and septic arthritis may complicate foot puncture wounds.[5] Cranial nerve neuropathies can occur in advanced malignant otitis externa with severe skull base osteomyelitis.[8] Systemic pseudomonal infections can lead to respiratory failure, shock, and death.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should be educated about the types of infections that Pseudomonas can cause and the risks associated with these infections.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Generally, clinicians should avoid prescribing antibiotics unless necessary. This prevents unnecessary costs, and prevents the emergence of resistant strains of bacteria, as is the case with all multi-drug resistant bacteria, including Pseudomonas. Targeted infection control practices aiming at the prevention of pseudomonal infections, especially in the hospital setting, are becoming increasingly important.[1] Analysis of various mechanisms of antibiotic resistance will be beneficial in determining the epidemiology and improve infection control.[12] An interprofessional team approach is needed to provide care to patients with known systemic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Inclusion of infectious disease, orthopedic surgery, and plastic surgery early in the management of the patients provides better outcomes and long-term results in terms of morbidity and mortality.