Continuing Education Activity

Obesity is the excessive or abnormal accumulation of fat or adipose tissue in the body that may impair health. Obesity has become an epidemic which has worsened for the last 50 years. In the United States, the economic burden is estimated to be about $100 billion annually. Obesity is a complex disease and has multifactorial etiology. It is the second most common cause of preventable death after smoking. This activity reviews the causes, pathophysiology, presentation, and complications of obesity and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in its management.

Objectives:

Recall the epidemiology of obesity.

Describe the pathophysiology of obesity.

Summarize the treatment options for obesity.

Explore modalities to improve care coordination among interprofessional team members in order to improve outcomes for patients affected by obesity.

Introduction

Obesity is the excessive or abnormal accumulation of fat or adipose tissue in the body that impairs health via its association with the risk of development of diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. It is a significant public health epidemic which has progressively worsened over the past 50 years. Obesity is a complex disease and has a multifactorial etiology. It is the second most common cause of preventable death after smoking. Obesity needs multiprong treatment strategies and may require lifelong treatment. A 5% to 10% weight loss can significantly improve health, quality of life, and economic burden of an individual and a country as a whole.[1][2][3][4][5]

Obesity has enormous healthcare costs exceeding $700 billion each year. The economic burden is estimated to be about $100 billion annually in the United States alone. The body mass index (BMI) is used to define obesity, which is calculated as weight (kg)/height(m). While the BMI does correlate with body fat in a curvilinear fashion, it may not be as accurate in Asians and older people, where a normal BMI may conceal underlying excess fat. Obesity can also be estimated by assessing skin thickness in the triceps, biceps, subscapular, and supra-iliac areas. Dural energy radiographic absorptiometry (DEXA) scan may also be used to assess fat mass.

Etiology

Obesity is the result of an imbalance between daily energy intake and energy expenditure, resulting in excessive weight gain. Obesity is a multifactorial disease caused by a myriad of genetic, cultural, and societal factors. Various genetic studies have shown that obesity is extremely heritable, with numerous genes identified with adiposity and weight gain. Other causes of obesity include reduced physical activity, insomnia, endocrine disorders, medications, the accessibility and consumption of excess carbohydrates and high-sugar foods, and decreased energy metabolism.

The most common syndromes associated with obesity include Prader-Willi syndrome and MC4R syndromes, less commonly fragile X, Bardet-Beidl syndrome, Wilson Turner congenital leptin deficiency, and Alstrom syndrome.

Epidemiology

Nearly one-third of adults and about 17% of adolescents in the United States are obese. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)'s 2011-2012 data, one out of five adolescents, one out of six elementary school-age children, and one out of 12 preschool-age children are obese. Obesity is more prevalent in African Americans, followed by Hispanics and Whites. Southern US states have the highest prevalence, followed by the Midwest, Northeast, and the West.

Obesity rates are increasing at a staggering rate worldwide, affecting over 500 million adults.

Pathophysiology

Obesity is associated with cardiovascular disease, dyslipidemia, and insulin resistance, causing diabetes, stroke, gallstones, fatty liver, obesity, hypoventilation syndrome, sleep apnea, and cancers.

The association between genetics and obesity is already well-established by multiple studies. The FTO gene is associated with adiposity. This gene might harbor multiple variants that increase the risk of obesity.

Leptin is an adipocyte hormone that reduces food intake and body weight. Cellular leptin resistance is associated with obesity. Adipose tissue secretes adipokines and free fatty acids, causing systemic inflammation, which causes insulin resistance and increased triglyceride levels, subsequently contributing to obesity.

Obesity can cause increased fatty acid deposition in the myocardium, causing left ventricular dysfunction. It has also been shown to alter the renin-angiotensin system, causing increasing salt retention and elevated blood pressure.

Besides total body fat, the following also increase the morbidity of obesity:

- Waist circumference (abdominal fat carries a poor prognosis)

- Fat distribution (body fat heterogeneity)

- Intra-abdominal pressure

- Age of onset of obesity

The body fat distribution is important in assessing the risk for cardiometabolic health. The distribution of excess visceral fat is likely to increase the risk of cardiovascular disease. [6][7][8] Ruderman et al [9] introduced the concept of metabolic obese normal weight(MONW) subjects with normal BMI suffer from metabolic complications normally found in obese individuals.

Metabolically healthy obese (MHO) Individuals have a BMI over 30 kg/m2 but do not have the characteristics of insulin resistance or dyslipidemia [10][11]

Adipocytes have been shown to have an inflammatory and prothrombotic activity, which can increase the risk of strokes. Adipokines are cytokines mainly produced by adipocytes and preadipocytes; in obesity, macrophages invading the tissue also produce adipokines. [12][13].

Altered adipokine secretion causes chronic low-grade inflammation, which may cause altered glucose and lipid metabolism and contribute to cardiometabolic risk in visceral obesity. [12]

Adiponectin has insulin-sensitizing and anti-inflammatory properties, and the circulating levels are inversely proportional to visceral obesity.

History and Physical

All children six years and older, adolescents, and all adults should be screened for obesity according to the United States Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendations.

Physicians should carefully screen for underlying causes contributing to obesity. A complete history should include:

- Childhood weight history

- Prior weight loss efforts and results

- Complete nutrition history

- Sleep patterns

- Physical activity

- Associated past medical histories like cardiovascular, diabetes, thyroid, and depression

- Surgical history

- Medications that can promote weight gain

- Social histories of tobacco and alcohol use

- Family history

A complete physical examination Should be done and should include body mass index (BMI) measurement, weight circumference, body habitus, and vitals.

Obesity focus findings like acne, hirsutism, skin tags, acanthosis nigricans, striae, Mallampati scoring, buffalo hump, fat pad distribution, irregular rhythms, gynecomastia, abdominal pannus, hepatosplenomegaly, hernias, hypoventilation, pedal edema, varicoceles, stasis dermatitis, and gait abnormalities can be present.

Evaluation

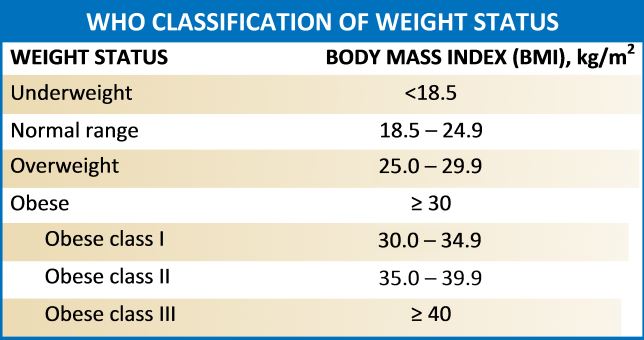

A standard screening tool for obesity is the measurement of body mass index (BMI). BMI is calculated using weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters.[14][15][16][17][18] Obesity can be classified according to BMI:

- Underweight: less than 18.5 kg/m2

- Normal range: 18.5 kg/m2 to 24.9 kg/m2

- Overweight: 25 kg/m2 to 29.9 kg/m2

- Obese, Class I: 30 kg/m2 to 34.9 kg/m2

- Obese, Class II: 35 kg/m2 to 39.9 kg/m2

- Obese, Class III: more than 40 kg/m2

The waist-to-hip ratio should be measured; in men, more than 1:1, and in women, more than 0:8 is considered significant.

Further evaluation studies like skinfold thickness, bioelectric impedance analysis, CT, MRI, DEXA, water displacement, and air densitometry studies can be done.

Laboratory studies include a complete blood picture, basic metabolic panel, renal function, liver function study, lipid profile, HbA1C, TSH, vitamin D levels, urinalysis, CRP, and other studies like ECG and sleep studies can be done for evaluating associated medical conditions.

Treatment / Management

Obesity causes multiple comorbid and chronic medical conditions, and physicians should have a multiprong approach to the management of obesity. Practitioners should individualize treatment, treat underlying secondary causes of obesity, and focus on managing or controlling associated comorbid conditions. Management should include dietary modification, behavior interventions, medications, and surgical intervention if needed.

The dietary modification should be individualized with close monitoring of regular weight loss. Low-calorie diets are recommended. Low calorie could be carbohydrate or fat restricted. A low-carbohydrate diet can produce greater weight loss in the first months compared to a low-fat diet. The patient's adherence to their diet should frequently be emphasized.

Behavior Interventions: The USPSTF recommends obese patients be referred for intensive behavior interventions. Several psychotherapeutic interventions are available, which include motivational interviewing, cognitive behavior therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, and interpersonal psychotherapy. Behavior interventions are more effective when they are combined with diet and exercise.

Medications: Antiobesity medications can be used for BMI greater than or equal to 30 or BMI greater than or equal to 27 with comorbidities. Medications can be combined with diet, exercise, and behavior interventions. FDA-approved antiobesity medications include phentermine, orlistat, liraglutide, semaglutide, diethylpropion, phentermine/topiramate, naltrexone/bupropion, setmelanotide, and phendimetrazine. All the agents are used for long-term weight management. Orlistat is usually the first choice because of its lack of systemic effects due to limited absorption.

Surgery: Indications for surgery are a BMI greater or equal to 40 or a BMI of 35 or greater with severe comorbid conditions. The patient should be compliant with post-surgery lifestyle changes, office visits, and exercise programs. Patients should have an extensive preoperative evaluation of surgical risks. Commonly performed bariatric surgeries include adjustable gastric banding, Rou-en-Y gastric bypass, and sleeve gastrectomy. Rapid weight loss can be achieved with a gastric bypass, and it is the most commonly performed procedure. Early postoperative complications include leak, infection, postoperative bleeding, thrombosis, and cardiac events. Late complications include malabsorption, vitamin and mineral deficiency, refeeding syndrome, and dumping syndrome.[19][20][21]

Weight loss associated complications

When weight loss is rapid, it is also associated with complications that include:

- Electrolyte abnormalities (esp, hypokalemia)

- Cardiac arrhythmias

- Hyperuricemia

- Cholelithiasis

- Mood and behavior alterations

Complications associated with bariatric surgery

- Strictures

- Wound dehiscence

- Ulcers

- Malabsorption

- Dumping syndrome

- Post-surgery diarrhea

- Vitamin and nutrient deficiency

- Anastomotic leaks

- Failed surgery

Differential Diagnosis

- Iatrogenic Cushing syndrome

- Kallman syndrome and idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism

- Generalized lipodystrophy

- Polycystic ovarian disease

Prognosis

Obesity has enormous morbidity and mortality rates. Obese patients have a high risk of adverse cardiac events and stroke. In addition, the quality of life is poor. Factors that worsen morbidity include:

- Age of onset of obesity

- Amount of central adiposity

- Severity of obesity

- Gender

- Associated comorbidity

- Race

Pearls and Other Issues

Management of obesity should also include prevention strategies with physical activity, exercise, nutrition, and weight maintenance.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The obesity epidemic continues to worsen and has become a public health issue. The management and prevention of obesity is best done with an interprofessional team that includes a bariatric nurse, surgeon, internist, primary care provider, endocrinologist, and a pharmacist. There is no cure for obesity, and almost every treatment available has limitations and potential adverse effects.

The key is to educate the patient on the importance of changes in lifestyle. All clinicians who look after obese patients have the onus to educate patients on the harms of the disorders. No intervention works if the patient remains sedentary. Even after surgery, some type of exercise program is necessary to prevent weight gain. So far, there is no magic bullet to reverse obesity- all treatments have high failure rates, and some, like surgery, also have life-threatening complications. There is an important need for collaboration between the fast-food industry, schools, physical therapists, dietitians, clinicians, and public health authorities to create better and safer eating habits.

Lifestyle changes alone can help obese people reverse the weight gain, but the problem is most people are not motivated to exercise.[21][22]