Continuing Education Activity

Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome (MTSS) is a common overuse injuries of the lower extremity, often seen in athletes and military personnel. It involves exercise-induced pain over the anterior tibia and is an early stress injury in the continuum of tibial stress fractures. This activity reviews the evaluation and management of medial tibial stress syndrome and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in improving care for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Describe the pathophysiology of medial tibial stress syndrome.

- Explain how to diagnose medial tibial stress syndrome.

- Describe treatment considerations for medial tibial stress syndrome.

- Review the importance of improving care coordination amongst interprofessional team members to improve outcomes for patients with medial tibial stress syndrome.

Introduction

Medial tibial stress syndrome (MTSS) is a frequent overuse lower extremity injury in athletes and military personnel. MTSS is exercise-induced pain over the anterior tibia and is an early stress injury in the continuum of tibial stress fractures.[1] It has the layman's moniker of “shin splints.”[2]

Etiology

Medial tibial stress syndrome is an overuse condition, specifically a tibial bony overload injury with associated periostitis, that clinicians commonly encounter in participants of recurrent impact exercise, such as running and jumping athletics as well as in military personnel.[3]

Epidemiology

The incidence of medial tibial stress syndrome ranges between 13.6% to 20% in runners and up to 35% in military recruits. Significant increasing loads, volume and high impact exercises can predispose to MTSS and further bone stress injury. Intrinsic risk factors include increases in the female gender, previous history of MTSS, high BMI, navicular drop (a measure of arch height and foot pronation), ankle plantar flexion range of motion, and hip external rotation range of motion.[2][4][5] Studies in military basic training recruits have linked vitamin D deficiency to an increased risk of stress injury.[6]

Pathophysiology

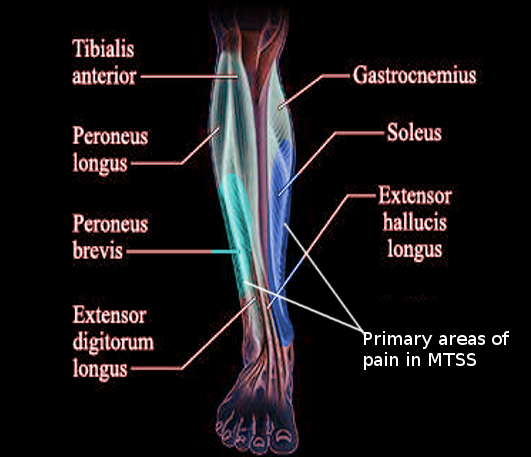

The underlying pathophysiologic process resulting in MTSS is related to unrepaired microdamage accumulation in the cortical bone of the distal tibia. There is typically an overlying periostitis at the site of bony injury, which also correlates with the tendinous attachments of the soleus, flexor digitorum longus, and posterior tibialis. Given the mechanical connection of Sharpey’s fiber’s, which are perforating fibers of connective tissue linking periosteum to the bone, the belief is that repetitive muscle traction may be the underlying cause of the periostitis and cortical microtrauma. However, it remains unclear if periostitis occurs before cortical microtrauma or vice versa.[3][7]

History and Physical

In the evaluation of lower extremity pain, reliable diagnosis of medial tibial stress syndrome is via history and physical examination.

Information elicited during history taking that supports MTSS includes:

- Presence of exercise-induced pain along the distal two-thirds of the medial tibial border

- Presence of pain provoked during or after physical activity, which reduces with relative rest

- The absence of cramping, burning pain over the posterior compartment &/or numbness/tingling in the foot

Physical examination should include palpation and inspection of the lower extremity. Physical exam findings that support MTSS include:

- Presence of recognizable pain reproduced with palpation of the posteromedial tibial border > 5 cm

- The absence of other findings not typical of MTSS (e.g., severe swelling, erythema, loss of distal pulses, etc.)

If the above components are present, then the diagnosis of MTSS can reliably be made. If the above components of history and physical examination are not present, MTSS is unlikely the cause of the lower extremity pain and suspicion and investigation should focus on a different cause of lower extremity pain.[8]

Evaluation

Medial tibial stress syndrome is a clinical diagnosis and can be reliably made by history and physical examination findings. However, imaging is often performed if uncertain of etiology or to rule out other common exercise-induced lower extremity injuries. In particular, the situation warrants imaging if concerned for a more significant tibial stress injury. Plain radiographs are normal in patients with MTSS and are often normal with an early stress fracture. Radiograph findings of the "dreaded black line" is indicative of stress fracture. MRI is the preferred imaging modality for identifying MTSS as well as a higher grade bone stress injury such as a tibial stress fracture. Nuclear bone scans are a reasonable alternative but are less specific and sensitive than MRI. MRI findings include periosteal edema and bone marrow edema. Nuclear bone scans demonstrate increased radionuclide uptake in the cortical bone with characteristic “double stripe” pattern. High-resolution CT is another viable advanced imaging option, but with lower sensitivity than MRI or nuclear bone scan.[3][4] Evaluating for vitamin D deficiency may also be warranted, especially for recalcitrant cases.

Treatment / Management

Management of medial tibial stress syndrome is conservative, mainly focusing on rest and activity modification with less repetitive, load-bearing exercise. There are no specific recommendations on the duration of rest required for resolution of symptoms, and it is likely variable depending on the individual. Additional therapies that have shown beneficial effect with low-quality evidence include iontophoresis, phonophoresis, ice massage, ultrasound therapy, periosteal pecking, and extracorporeal shockwave therapy. Therapies that have yielded no benefit include low-energy laser therapy, stretching, strengthening exercises, lower leg braces, and compression stockings. Regarding prevention, a recent study on naval recruits showed prefabricated orthotics reduced MTSS.[9][10][11]

For recalcitrant cases with a limited or slow response to rest and activity modification, optimizing calcium and vitamin D status and gait retraining may improve recovery and prevent further progression of the injury.[12][13]

Differential Diagnosis

Given the location on the lower extremity, the differential diagnosis includes the following: tibial stress fracture, chronic exertional compartment syndrome (CECS), and vascular etiologies (e.g., functional popliteal artery entrapment syndrome, peripheral arterial disease, etc.).

Tibial stress fractures can be difficult to distinguish from MTSS and are likely part of the same continuum of tibial bone stress injury. Anterior cortex stress fractures are more common than posteromedial tibial stress fractures and are distinguished by point tenderness (<5 cm) along the tibia. Radiographs may reveal the "dreaded black line," and MRI can help determine the severity of the stress injury.[1]

Chronic exertional compartment syndrome (CECS) is considered a disorder of muscular origin and presents similarly with exercise-induced lower extremity pain that is also diffusely located. It often involves both extremities, relieved by rest, and may have additional symptoms such as paresthesias, pallor, cold skin temperature, and loss of pulses in the distal lower extremity. CECS diagnosis is made by measuring intramuscular compartment pressures.

Functional popliteal artery entrapment syndrome (FPAES) and peripheral arterial disease (PAD) both manifest as claudication. FPAES is thought to be due to anatomic variations or hypertrophy of the musculature in the popliteal fossa leading to popliteal artery compression with increased activity. FPAES diagnosis is by stress arteriography. PAD is often due to atherosclerosis and is diagnosed by arteriography or Doppler ultrasound examination.[10]

Prognosis

Full recovery is expected with adequate rest and activity modification.

Complications

Acute complications for athletes and military personnel include pain leading to decreased performance and/or time away from training/participation. The presumption is that medial tibial stress syndrome (MTSS) may progress to a tibial stress fracture, as cortical microtrauma may evolve into cortical fracture. However not every patient that experiences MTSS develops a tibial stress fracture.[3][4] Severe tibial stress fractures may require surgical intervention.

Deterrence and Patient Education

By definition, medial tibial stress syndrome is a stress reaction to the tibia as a result of overuse. Therefore, deterrence focuses on patient education of proper biomechanics and graded exercise regimen as well as avoiding overtraining. Optimizing vitamin D and calcium has shown to reduce the incidence of stress fractures in military recruits and should be a consideration. Athletes and military personnel would benefit from instructor awareness of MTSS and the necessity of properly scaled training programs with adequate recovery time.

Pearls and Other Issues

In recalcitrant cases that do not resolve with adequate rest and conservative management, the clinician should consider optimizing vitamin D status and consider gait retraining.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Medial tibial stress syndrome is a common exercise-induced lower extremity injury. The clinician can reliably diagnose MTSS by history and physical. However, advanced imaging with MRI (preferred) or nuclear bone scan can help rule out tibial stress fracture if concern remains. Management focuses on rest and activity medication, with some alternative therapies yielding low-quality evidence for a beneficial effect. In addition to rest and activity modification, further evaluation by a physical therapist or rehabilitation nurse may be beneficial for a trial of alternative therapies as well as structural analysis for contributing anatomic risk factors.