Continuing Education Activity

Clinical prevention of HIV infection and AIDS is the cornerstone of controlling the global HIV pandemic that has now killed more than 40.4 million people globally, including 1.5 million children. Two-thirds of new HIV infections occur in Africa, primarily via heterosexual sexual contact. In the United States, gay and bisexual men and people who inject drugs are most commonly affected.

While a cure remains out of reach, HIV infection is now seen as a chronic illness due to the effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy. Universal Test and Treat, Treatment as Prevention, preexposure prophylaxis, and postexposure prophylaxis are significant advancements that make the goal of halting the global pandemic of HIV feasible. Although the incidence of HIV infections is decreasing in the United States and worldwide, specific populations face rising rates due to socioeconomic factors.

This activity reviews the risk factors for HIV transmission, methods of reducing the risk of HIV transmission, implementation considerations for specific population groups, and the role of clinical, public health, and other interdisciplinary team members in decreasing the global burden of this disease.

Objectives:

Apply an understanding of individual, clinical, and socioeconomic risk factors to recommend appropriate, patient-centered clinical prevention measures to people living with or at risk of HIV, according to World Health Organization, Centers for Disease Control, or local guidelines.

Improve capacity to test patients for HIV and rapidly link to appropriate antiretroviral therapy, such as preexposure prophylaxis, postexposure prophylaxis, and treatment as prevention to reduce the risk of HIV transmission.

Communicate openly and nonjudgmentally with patients, ensuring they are informed about HIV prevention options, risks, and benefits.

Collaborate with interdisciplinary teams, including public health professionals, researchers, and community organizations, to promote general awareness of HIV prevention and testing, improve the quality of HIV prevention services, overcome barriers related to stigma and socioeconomic factors, and support people living with or at risk of HIV.

Introduction

HIV can infect individuals of any age, gender, race, or social class. Due to the effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy (ART), HIV infection is now seen as a manageable chronic disease. However, despite significant advancements in controlling the virus, the disease remains a significant global health concern fed by and contributing to inequities.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates more than 630,000 people died from HIV-related causes in 2022.[WHO. HIV Data and Statistics. 2023] Thirty-nine million people are living with HIV, of whom two-thirds are living in Africa, and 1.5 million are children aged 0 to 14. In addition, 1.3 million people acquire HIV each year, most commonly from heterosexual contact.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that 1.2 million people in the United States (US) had HIV at the end of 2021, of which 87% were aware.[CDC. Basic Statistics. 2023] Male-to-male sexual (MSM) contact accounts for 67% of all new HIV diagnoses in the United States, with heterosexual contact accounting for 22% and intravenous drug use 7%.[CDC. Basic Statistics. 2023] High-risk groups included MSM, transgender individuals, people with multiple partners or who do not use condoms, individuals who trade sex for money, goods, or services, people living in locations where the incidence is 3% or greater, and individuals who have had sexually transmitted infections (STIs) or who share injection drug needles, syringes or other equipment, amongst others.[1] The number of new diagnoses in the United States each year decreased by approximately 7% from 2017 to 2021.[CDC. Basic Statistics. 2023]

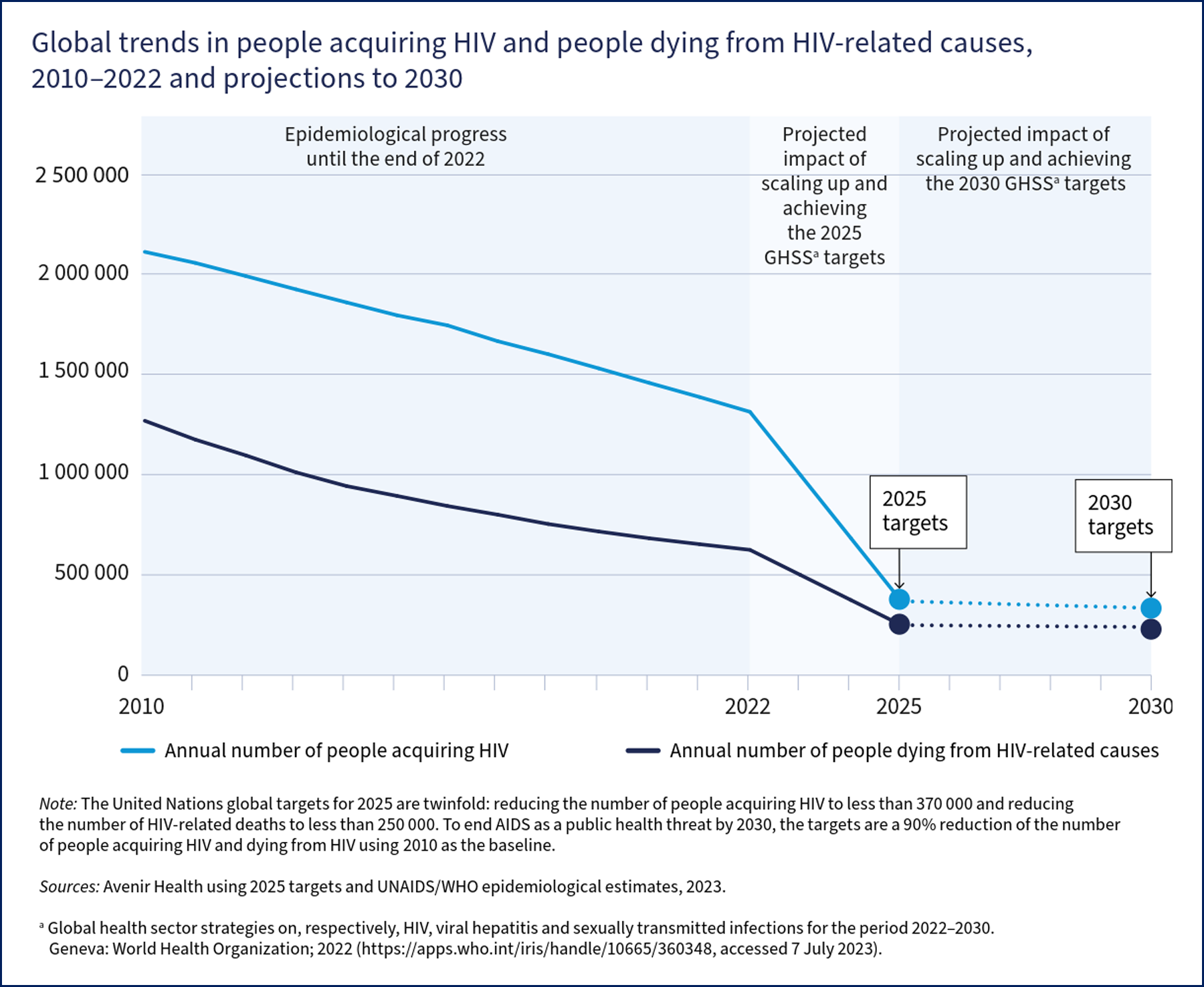

Targets and initiatives set by the United Nations (UN), the WHO, and individual countries' centers for disease control have fostered immense progress in scaling up testing and implementing antiretroviral therapy (ART. However, knowledge of HIV status, use of preventive services, and access to and retention in care remain suboptimal in the United States and worldwide, with large inequities between populations. The Joint UN Programme for HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) has set "95-95-95" goals for 2025.

- 95% of all individuals with HIV will know their status

- 95% of all those who have HIV will receive antiretroviral therapy

- 95% of all people on ART will achieve viral suppression

The projected impact of this will be fewer than 370,000 people acquiring HIV and fewer than 250,000 people dying from HIV in 2025 (see Image. Global Trends in people acquiring or dying from HIV).

This article focuses on biomedical HIV prevention approaches for clinicians as part of an overall public health approach to achieving global and national targets and decreasing the global burden of this disease. It reviews the modes of transmission of HIV, pharmaceutical strategies for at-risk populations, implementation considerations for select populations, and select public health measures of relevance across the interdisciplinary team.

See "Monitoring, Surveillance, and Reporting" under "Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes" in this article for further information on the 95-95-95 goals. See StatPearls' companion topics, "HIV and AIDS" and "HIV Antiretroviral Therapy," for further information on these topics.

Issues of Concern

HIV infection can be transmitted through sexual intercourse, exposure to infected blood, or perinatally. The mechanism of transmission, viremia in the source individual, general health and presence of other STIs in the exposed individual, and use of preventive measures all affect the actual transmission rate. The development of effective, patient-centered clinical programming and services to prevent HIV depends on an understanding of these factors.

See the "Other Issues" section below for other factors affecting transmission rates in specific groups of people, such as poverty, stigma, living in a closed setting, and access to health services.

Viremia in the Source Individual

Each log increase in viral load is estimated to increase the risk of HIV transmission 2.5-fold, with no viral transmission events noted from individuals who had a baseline viral load of less than 1500 copies/mL.[2] Patients with acute infection have high viral load and viral shedding in bodily fluids, putting them at high risk for transmission of the infection to their contacts.[3][4] On the other hand, sustained viral suppression minimizes the risk of transmission in serodiscordant couples.[5]

Sexual Transmission

Sexual transmissions account for the bulk of new infections in the United States and worldwide. Receptive anal intercourse is the highest-risk sexual practice for HIV transmission, with approximately 138 infections per 10 000 exposures with an infected source, while insertive anal intercourse has an 11 in 10,000 exposure risk.[6][CDC. HIV Risk Behaviours. 2019] The risk of receptive and insertive vaginal intercourse is 8 and 4 per 10 000 exposures, respectively. The presence of other STIs, particularly those that are ulcerative, can result in HIV detection in bodily fluids, even in the presence of adequate serum control of HIV.[7][8][9][10]

Available barrier methods for the prevention of HIV transmission and other STIs include male and female condoms and dental dams. Male condoms remain the mainstay of barrier HIV prevention measures as they are cheap, readily available, effective, and protect against many other STIs. A Cochrane review found that consistent use of condoms during every sexual encounter resulted in an 80% decrease in HIV incidence.[11] Another meta-analysis showed condoms reduce HIV transmission by more than 70% when used consistently by HIV-serodiscordant heterosexual couples.[12] Therefore, the American College of Physicians and the HIV Medicine Association recommend the wide availability of condoms and education regarding their proper use to minimize the risk of HIV transmission.[13]

The use of male condoms is primarily the decision of the insertive male partner, with the receiving partner having little control. Female condoms have the advantage of transferring decision-making to the female, yet the method lacks widespread acceptance and understanding. Dental dams can be used during cunnilingus or anilingus, although these are likewise not commonly integrated into regular use.

Voluntary male circumcision is an effective preventive strategy to reduce the risk of heterosexually acquired HIV infections in settings with generalized epidemics in eastern and southern Africa.[WHO. Global Health Sector HIV strategies. 2022] One study from South Africa reported a 60% decrease in the risk of HIV infection amongst circumcised males as compared to uncircumscribed after controlling for behavioral factors, condom use, and health-seeking behaviors.[14] Adverse events related to circumcision are infrequent (1.5%) and usually resolve quickly.[15]

Blood-Borne Transmission

Injection drug use currently represents the most significant risk of HIV transmission via the blood-borne route, with an estimated 63 infections for every 10,000 exposures from an infected source. Sterile syringe programs (SSPs) are highly effective in decreasing the risk of HIV via this route but are often underutilized and face regulatory restrictions in some places.

The healthcare system has nearly eliminated blood transfusion transmission of HIV by effectively screening donors and testing all blood products. Otherwise, for every 10,000 infected blood transfusions, HIV will be transmitted to approximately 9,250 people recipients (range 8,830 to 10,000).[CDC. HIV Risk Behaviours. 2019][16] Universal precautions for healthcare workers effectively decrease occupational exposure. The risk of HIV transmission from the reuse of needles and other medical equipment in healthcare settings has markedly decreased since 2000 when the WHO began safe injection campaigns worldwide. In 2010, the global proportion of all HIV transmissions attributed to unsafe medical injections was estimated to have decreased by 87% in the previous 10 years, from a range of 4.6% to 9.1% to one of 0.7% to 1.3%.[17] Similar decreases were seen for Hepatitis B and C viruses (HBV and HCV). Iatrogenic risks of HIV transmission remain for people requiring medical care during times of political strife, war, or migration, where infection prevention and control procedures may be substandard.

Maternal-Infant Transmission

Without treatment, the risk of vertical transmission from mother to infant is approximately 20% to 30%.[HHS. Perinatal HIV Clinical Guidelines. 2023] The effectiveness of treatment in preventing transmission depends on how early treatment is initiated and the viral load during pregnancy. ART with viral suppression throughout pregnancy and childbirth and ART for the infant for 4 to 6 weeks after birth has been shown to decrease the overall rate of HIV transmission to 0.1% to 0.5%.[CDC HIV Basics - Transmission. 2022][HHS. Perinatal HIV Clinical Guidelines. 2023] The risk of vertical transmission was shown to be around 1% for infants born to mothers with a viral load of 50 to 399 copies/mL near delivery, while the risk of transmission was 0.09% for mothers who had a viral load of less than 50 copies/mL.[18]

Clinical Significance

Antiretroviral medications used as preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP), postexposure prophylaxis (PEP), or treatment as prevention (TasP) are highly effective in decreasing the transmission of HIV. A cornerstone of any HIV prevention strategy, antiretrovirals should be offered to all at-risk individuals. PrEP and TasP require intensive patient engagement and frequent follow-up visits at a health facility. They must be given in conjunction with access to condoms, regular testing for STIs, and intensive counseling for behavioral risk reduction, including safer sex or injection practices as appropriate. Patients must be advised that antiretrovirals do not prevent other STIs or pregnancy.

People most at risk of HIV often have challenges with adhering to therapy due to multiple structural barriers, and loss to follow-up is common.[1] PrEP navigators, telehealth or telephone check-ins, smartphone reminders, delivery services, directly observed therapy, and pillboxes may enhance adherence. Substance use treatment should be integrated into HIV treatment and preventive services.

Treatment as Prevention

An overwhelming body of evidence supports the TasP approach, also known as "undetectable=untransmittable" or "U=U." This approach engages patients and providers to treat HIV for the patient's health and to reduce the risk of sexual transmission to others. Clinical data only support U=U for sexual transmission. Even with undetectable viral loads, HIV transmission still occurs perinatally and via breast milk, and TasP's effectiveness in preventing exposure through blood has not been determined.[NIH. HIV Antiretroviral Guidelines - TasP. 2019]

From 2011 to 2019, the large HPTN052, Partner 1 and 2, and Opposites Attract studies followed mixed-status MSM and heterosexual couples to assess HIV transmission rates with the partner living with HIV on ART. These showed 100% efficacy in preventing HIV transmission if ART is taken as prescribed and an undetectable viral load is achieved (defined as <200 copies of HIV-1 RNA/mL of plasma).[19][20] Subsequently, combined studies across 2600 couple-years of follow-up and more than 126 000 sexual acts estimate the risk of genetically-linked HIV transmission per 100 couple-years of vaginal or anal intercourse without condoms or the use of PEP or PrEP by the HIV-negative partner is zero (CI, 0.00 to 0.14).[CDC. HIV Risk and Prevention Estimates. 2022] The HPTN052 study estimates TasP effectiveness to be 96% amongst heterosexuals, including periods when pills were not taken.[21]

For both clinical and public health outcomes, HIV treatment with antiretroviral therapy as soon as possible and preferably within 7 days after diagnosis is recommended for all individuals with HIV, regardless of their CD4 count or the stage of the disease.[HHS. Adolescents-Adults ARV Guidelines. 2023][WHO. Global Health Sector HIV Strategies. 2022] Uptake and adherence remain suboptimal in the United States and worldwide. Many factors contribute to this, including lack of access to quality healthcare, poor linkage between testing and treatment, uneven knowledge gaps in the understanding of undetectable = untransmittable, personal factors, and the social context in which HIV infection occurs.[34][22][23][24] For example, the CDC estimates that 20% of individuals under clinical care for HIV in 2015 did not achieve viral suppression, and 40% did not maintain it for more than 12 months.[19]

Supporting clients to achieve and maintain an undetectable viral load is critical to achieving the maximal benefit from TasP, including support to take ART as prescribed, test viral load frequently until viral suppression is achieved (usually within 6 months) and every 3 to 4 months after that, and maintain long term adherence to therapy. Viral load increases within a few weeks if treatment is stopped.[19] Patient-centered interventions, such as text reminders, community health workers and advocates, and men- and youth-friendly services may facilitate patient linkage to care and adherence to treatment.[24][WHO. Men and HIV. 2023]

See StatPearls' companion topic "HIV treatment" for further information on treatment indications, options, side effects, and contraindications.

Preexposure Prophylaxis

Multiple large trials demonstrate the efficacy of oral PrEP in decreasing HIV transmission risk in people at high risk of acquiring HIV across sex, age, risk category, and study duration. The risk of HIV is up to 92% lower for people who take oral PrEP consistently compared to those who take a placebo. The effectiveness of PrEP is significantly reduced with inconsistent use.[CDC. PrEP HIV Prevention in the US. 2021] The first long-acting injectable PrEP, cabotegravir, was approved in the United States in 2021. Men, women, and transgender women in the cabotegravir arms of 2 large studies had a 69% to 90% lower chance of contracting HIV through sexual transmission than those taking tenofovir disiproxil fumarate (TDF)/emtricitabine.[CDC. PrEP HIV Prevention in the US. 2021]

Updated local guidelines should be consulted when assisting patients in making decisions for PrEP as new indications and agents become available. The CDC updated its recommendations for the United States in 2021, and the International Antiviral Society–USA Panel's Antiretroviral Drugs for Treatment and Prevention of HIV Infection in Adults was updated in 2022.[CDC. PrEP HIV Prevention in the US. 2021][25] In August 2023, the US Preventive Services Task Force published an evidence report and systematic review of PrEP in advance of updating its guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents with HIV.[1]

All adults and adolescents who are sexually active, inject nonprescribed drugs, or have a substance use disorder should be informed about PrEP, and people identified to be at increased risk should be offered PrEP.[25][WHO. HIV Factsheet. 2023] The CDC considers individuals to be at risk from sexual contact if they have had anal or vaginal sex in the past 6 months and a partner with HIV (especially if viral load is unknown or detectable), a bacterial STI in the last 6 months, or a history of inconsistent or no condom use with a partner(s). People who inject drugs (PWID) and who have an injecting partner with HIV or share injection equipment are also at risk.[CDC. PrEP HIV Prevention in the US. 2021] Due to many peoples' hesitation to share details of their sexual and drug use behaviors, PrEP should be provided to all patients who request it, regardless of known risk factors.[25]

The choice of PrEP regime should be based on a discussion between the person and provider and based on the person's risk factor profile, comorbid conditions, preference for oral or injectable medications, and ability to take medications reliably, in addition to the adverse effect profile and cost of the medication if not covered through insurance or pharmaceutical-sponsored programs.[1]

Oral PrEP can be taken as 1 tablet once a day of TDF/emtricitabine (300 mg/200 mg, respectively) by all people at risk of acquiring HIV, including those who are pregnant or breastfeeding.[1] One tablet orally of tenofovir alafenamide (TAF)/emtricitabine (25 mg/200 mg, respectively) daily is an equal alternative for cisgender men and others at risk who do not have receptive vaginal sex, including those at risk solely due to injection drug use. It is preferable to TDF for people in these populations with a creatinine clearance between 30 to 60 mL/min or known osteoporosis or osteopenia. TAF/emtricitabine is not indicated for women at risk of HIV via vaginal penetration, as no trial data is available for this population.[1]

MSM who can identify high-risk sexual events at least 2 hours beforehand can take oral PrEP "on-demand."[1] Also known as episodic or "2:1:1", on-demand PrEP is taken as 2 tablets orally of TDF/emtricitabine at least 2 hours, but up to 24 hours before the sexual encounter and then 1 tablet on each of the 2 days after the sexual encounter.[CDC. PrEP HIV Prevention in the US. 2021] TAF/emtricitabine cannot be used for episodic PrEP. Episodic PrEP is not indicated for people at risk of HIV from receptive vaginal or neovaginal sex or injection drug use due to the lack of studies in these populations. Episodic therapy must be used with caution in transgender women receiving gender-affirming therapy, as PrEP may take longer to reach adequate concentrations in rectal tissues to prevent HIV.[1]

Cabotegravir can be used for the prevention of sexual transmission of HIV across populations, including those PWID who are also at risk of acquiring HIV through sex and pregnant people.[1] It is given as a gluteal intramuscular injection every 2 months.

PrEP should be started as soon as possible for those at risk, including on the same day if the patient is willing and has no signs or symptoms of acute HIV, a documented negative HIV test result no more than 1 week prior, and no contraindicated medications or conditions. An HIV antigen-antibody test is done after initiation of PrEP if the decision to start is based on a rapid or point-of-care HIV test. As TDF can rarely cause renal disease, patients opting for oral PrEP must have a creatinine clearance of at least 30 mL/min at baseline and every 6 months after that. Testing of blood for HBV antigens informs the choice of PrEP as TDF/emtricitabine is also used to treat HBV; the presence of HBV would not exclude using PrEP but would need to be evaluated separately for use.

The patient must have a negative HIV test result at least every 3 months before receiving each prescription refill or at least every 2 months before each injection, as taking PrEP with preexisting HIV can result in resistance and suboptimal viral control.[CDC. PrEP HIV Prevention in the US. 2021]

Postexposure Prophylaxis

The decision to begin PEP is based on calculating the risk of taking PEP against the risk of acquiring HIV after a specific exposure. HIV risk depends on the likelihood that the source person has HIV and, if so, whether the viral load is detectable and the type of exposure, for example, the type of sexual encounter, size of the needle in a needle stick exposure, and type and size of mucosal exposure.

Nonoccupational PEP (nPEP) is given when an individual seeks medical treatment within 72 hours after being exposed in a nonoccupational setting to semen, vaginal fluid, or blood that is confirmed or suspected to be infected with HIV. If the source individual is known not to have HIV by testing or the exposure is more than 72 hours in the past, nPEP is not indicated. If the source is known to have HIV, the type of exposure needs to be evaluated for the significance of the risk. If the HIV status of the source patient is unknown, evaluation is on a case-by-case basis. A rapid HIV test should be obtained, and an assessment made for any other potential exposure-related risks such as STIs, hepatitis B and C, and pregnancy.[26] In occupational PEP (oPEP), the opportunity to test and monitor the source person exists in most cases.

In both oPEP and nPEP, antiretroviral therapy must be started as soon as possible, preferably within 72 hours of exposure, and continued for 4 weeks. The preferred regimen for nPEP and oPEP for otherwise healthy adults and adolescents is 1 tablet of TDF/emtricitabine once daily with either raltegravir 400 mg twice daily or dolutegravir 50 mg once daily for 4 weeks.[26]

Patients seeking nPEP should be referred for PrEP if they are at repeated risk for HIV infection or if nPEP has been sought more than once in the past 12 months. Postexposure prophylaxis regimens have few adverse effects and minimal risk of HIV resistance, yet use among healthcare providers is still low. Providers should take full advantage of the PEP consultation service for clinicians, a live hotline available from 9 am to 2 am Eastern time in the United States at 1-888-448-4911.[27]

Other Issues

More than 40 years of global experience in preventing HIV has demonstrated a patient-centered approach is required for optimal prevention and treatment of HIV. Clinicians must be aware of groups at higher risk of transmission to tailor and improve the quality of services offered by programs to people with or at high risk of HIV.

Pregnant People and their Infants

The global reduction in HIV transmission from mother to child is a significant public health victory, with universal testing and the offering of treatment being the cornerstones of prevention. The WHO has the triple aim to eliminate maternal-child transmission of HIV, HBV, and syphilis.[WHO. Global Health Sector HIV Strategies. 2022] All individuals, irrespective of risk status, should be tested if trying to conceive and as early as possible in pregnancy. Those who are at higher risk should have repeat testing in the third trimester, including in areas with HIV incidence.[HHS. Perinatal HIV Clinical Guidelines. 2023] Some states and territories mandate repeat third-trimester testing. HIV transmission is further reduced if rapid HIV testing is performed at the time of delivery if the HIV status of a client is unknown or if they live in a high-incidence area.[28]

Testing must be paired with the immediate offer of ART with a recommended 3-drug regime preconception or as early as possible during pregnancy.[25] The necessary support should be given to help pregnant persons achieve undetectable levels as soon as possible.[HHS. Perinatal HIV Clinical Guidelines. 2023] Give Zidovudine intrapartum to all people with a high viral load or at risk of high viral load whether or not they are on ART. All infants exposed to HIV in the perinatal period should be started on ART within 6 hours of birth.

Breast milk can also transmit HIV to the child. Using infant formula or donor human milk instead of breast milk eliminates the risk. Individuals who achieve and maintain viral suppression may opt to breastfeed with the understanding that the risk of transmission to the child is less than 1% but not zero.[HHS. Perinatal HIV Clinical Guidelines. 2023]

Gay, Bisexual, and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men

As the group with the highest rate of HIV in the US, people who have male-to-male sexual contact must be a priority group for HIV prevention. Anal intercourse is the highest risk sexual behavior for HIV transmission, with receptive anal sex being 13 times riskier than penetrative. Gay and bisexual men are also at higher risk of STIs, which increases the risk of HIV transmission. While a slightly lower percentage of gay and bisexual men knew their HIV status than other people with HIV, a slightly higher percentage is received and retained in HIV care and achieves viral suppression.[CDC. HIV and Gay and Bisexual Men. 2021] Eighty-five percent of gay and bisexual men without HIV in the United States are aware of PrEP; 25% use it.[CDC. HIV and Gay and Bisexual Men. 2021]

However, inequalities exist across subpopulations. Black/African American gay and bisexual men are the subpopulation most affected by HIV in the United States, comprising 26% of all new HIV diagnoses and 37% of new diagnoses in gay and bisexual men in 2019. Hispanic/Latino gay and bisexual men are likewise disproportionately affected, with 22% of all new HIV diagnoses and 26% of new diagnoses in gay and bisexual men occurring in Hispanic and Latino men in 2019.[CDC. HIV and Gay and Bisexual Men. 2021]

Gay and bisexual men in these groups are less often aware of their HIV status and have lower awareness and use of PrEP as compared to other gay and bisexual men. While reception and retention in care and rate of viral suppression are lower in Black/African American gay and bisexual men as compared to other gay and bisexual men, this is not the case for Hispanic/Latino gay and bisexual men.[CDC. HIV and Gay and Bisexual Men. 2021]

Black/African American gay and bisexual men are at greater risk of being exposed to HIV because of the higher prevalence of HIV in this group, greater likelihood of sexual partners of the same race, and lower use of PrEP as compared to other ethnicities. Hispanic/Latino gay and bisexual men tend to have older sexual partners, which may increase the likelihood of exposure to HIV.[CDC. HIV and Gay and Bisexual Men. 2021] Addressing racism, discrimination, HIV stigma, and homophobia, compounded by poverty, homelessness, incarceration, and other factors, can further limit access to high-quality healthcare services and contribute to poor health outcomes.

People who Inject Drugs

About 3.7 million people in the United States injected drugs in 2018, a number that increased sizeably in the 10 years prior.[29] In 2019, 1.6% of all high school students reported having injected drugs at least once.[CDC. Syringe Services Programs. 2023] PWID of all genders who share syringes or other drug equipment are at a very high risk of becoming infected with HIV, Hepatitis B and C, and other pathogens due not only to injection drug use but also because of at-risk sexual encounters.

Nine in 10 PWID with HIV in the United States knew they had the virus in 2018. However, this group of people may experience barriers to care, with 64% reporting experiencing homelessness, 31% being incarcerated, and 21% having no health insurance. Straight male PWID with HIV, in particular, had lower rates of linkage to care, retention in care, and viral suppression, while women and gay and bisexual men did not. This may be due to the over-representation of racialized men among PWID. Greater efforts are necessary to increase the rates of linkage and retention in care and viral suppression.

Approximately 32% of all PWID in the United States share syringes, with increased rates in younger people. Almost half of those aged 18 to 24 report sharing.[CDC. Syringe Services Programs. 2023] The most effective means for PWID from transmitting or acquiring HIV is to stop injecting. However, individuals may be unable or unwilling to do so at present, or they may have little or no access to effective treatment services. The WHO and other HIV experts recommend a comprehensive set of harm reduction services for this population, including SSPs, opioid agonist maintenance therapy for those dependent on opioids, and the community distribution of opioid antagonist therapy for the management of overdose, in addition to services for testing, diagnosis, and management of HIV.[30][WHO. Global Health Sector HIV Strategies. 2022]

SSPs are highly effective at decreasing rates of HIV, viral hepatitis, and other infections, approximately halving the incidence of HIV and HCV.[CDC. Syringe Services Programs. 2023] They are cost-saving to the health care system and do not increase illegal drug use or crime. SSPs are also an effective mechanism to reach PWID, an often highly marginalized population, linking people to PrEP, providing harm reduction teaching, increasing access to condoms, and connecting individuals to HIV testing and treatment facilities.[31] Teaching must increase understanding of risk as the lower perceived risk of HIV lowers PrEP uptake among youth and women who inject drugs.[32][33] People who regularly use an SSP are 5 times as likely to enter treatment for a substance use disorder than those who have never used one.

Opioid substitution therapy can decrease drug-related behaviors that can have a high risk of HIV transmission.[34] Effective opiate replacement therapy improves antiretroviral adherence. This is especially important as comorbid substance use disorder is associated with worse treatment outcomes in patients living with HIV.[35]

Populations Facing Socioeconomic Barriers to Care

Multiple barriers currently prevent individuals who are racialized, gender-diverse, disabled, migrant, unhoused, incarcerated, impoverished, or otherwise marginalized from having full access to HIV testing, care, and prevention.[19][22][36] Individuals in these groups may have lower knowledge of their HIV status, lower awareness of risk, lower awareness of PrEP and other prevention measures, and lower rates of viral suppression. Addressing inequities at the healthcare provider, social, and system levels will be key to achieving the 95-95-95 goals.[WHO. Global Health Sector HIV Strategies. 2022]

Multiple sources of evidence support the notion that socioeconomic factors and government policies affect access to prevention and care services, leading to poorer health outcomes. For example, an analysis using 2007 data from the National Behavioural Surveillance System for Heterosexuals showed the prevalence of HIV to be 2.1% for people living in urban poverty areas, more than 20 times greater than the rate amongst all heterosexuals in the United States.[CDC. HIV - Communities in Crisis. 2019] Household income was inversely correlated with HIV prevalence. People unemployed due to disability lived with HIV at 7 times the rate of those who were employed. The prevalence of HIV in areas of urban poverty in the United States was similar to that of low-income countries with generalized epidemics, such as Ethiopia and Haiti.[CDC. HIV - Communities in Crisis. 2019] Unlike in the entire US population, rates did not differ significantly by race or ethnicity in populations living in urban poverty.

Despite significant advances in HIV prevention science, stark disparities in HIV prevalence and incidence persist along racial lines in the United States. Black/African American and Hispanic/Latino men living in poor areas have 5.4 and 2.9 times higher HIV incidence rates than other men in the United States.[CDC. HIV SDH Surveillance 2021. 2023] The gap is even larger for Black/African American and Hispanic/Latino men living in higher-wealth areas. For Hispanic/Latino gay and bisexual men, the fear of disclosing their immigration status is a barrier to seeking HIV testing, prevention services, or treatment.[CDC. HIV and Gay and Bisexual Men. 2021][CDC. HIV and Gay and Bisexual Men. 2021]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

A healthcare team approach is required to support individuals with HIV or at high risk of HIV and to ensure factors within organizational, community, and policy environments support the prevention of HIV. Many of these are the role of clinicians within the full spectrum of their expertise. Others are the individual or shared roles of public health agencies and organizations, academics, health care administrators, and community agencies.

While this article focuses on modes of transmission, pharmaceutical interventions, and specific at-risk populations, programs and strategies to prevent the transmission of HIV must be based on a comprehensive public health approach. HIV prevention initiatives from the WHO, national departments of health, CDC, and other organizations contain health sector strategies appropriate to various settings.[WHO. Global Health Sector HIV Strategies. 2022][US Gov. National HIV/AIDS Strategy. 2023]

Raising Awareness of Individual HIV Prevention Measures

Public and patient education remains a cornerstone for primary HIV prevention, with clinicians, public health agencies and organizations, and community partners all having a role to play. All adolescents and adults who are sexually active or inject nonprescribed drugs should be aware of measures to prevent the acquisition of HIV.[25][WHO. HIV Factsheet. 2023]

- Use male or female condoms consistently during penetrative sex.

- Get tested regularly for HIV and STIs.

- Use antiretroviral drugs for preexposure prophylaxis if recommended by a clinician.

- Use harm reduction services where available for people who inject and use nonprescribed drugs.

- Consider voluntary medical male circumcision if living in a setting with a generalized epidemic.

For those living or at high risk of acquiring HIV, interprofessional teams, including nurses, pharmacists, and mental health professionals, are required to reinforce these messages, ensure adherence to medications, and provide a linkage to ancillary services to improve linkage to and retention in care.

Measures targeting healthcare providers are also necessary as some may not be aware of prevention measures such as TasP/U=U or have judgmental attitudes that lead to a lack of sharing and promoting information about it with people at risk of or living with HIV.[22] Education targeting healthcare providers should be broad to ensure information and support are available to the client where and when needed. This includes generalized primary care practitioners well known to the client and others with less frequent connections, such as community health service providers, pharmacists, or specialist physicians.

Testing

Easy access to HIV testing is the pivotal first step in HIV care and prevention. Testing facilitates early diagnosis and treatment of HIV, improving the long-term health of individuals infected with HIV. As nearly 40% of all HIV infections are transmitted by people who are unaware of their HIV status, testing is also an essential prevention measure.[CDC. HIV Testing. 2022]

The CDC recommends screening broadly within the US population.[CDC. HIV Testing. 2022]

- At least once for everyone between the ages of 13 and 64 as part of routine health care

- In healthcare settings for all adolescents, adults, and pregnant individuals

- At least once a year for anyone with a higher risk of acquiring HIV, including those who have more than one partner since their last test, been diagnosed with an STI, shared needles, exchanged sex for drugs or money, had sex with someone with HIV, or have had same-sex intercourse with a man

- For all pregnant people before or as soon as possible after conception and in the third trimester if risk factors exist.[HHS. Perinatal HIV Clinical Guidelines. 2023]

There are 3 main types of HIV tests, with variable times between exposure to HIV and test positivity. None can detect the virus immediately after diagnosis. Generally speaking, HIV can be detected earlier in venous blood than that from a finger stick or oral fluid.[CDC. HIV Testing. 2022]

- Antibody tests can detect HIV within 23 to 90 days after exposure to HIV. They are the technology used for most rapid tests and the only Food and Drug Administration-approved HIV self-test.

- Antigen-antibody tests detect the viral p24 antigen and antibodies the immune system develops in response to it. They are commonly used for laboratory testing, detecting HIV in 18 to 24 days after exposure. A rapid fingerstick antigen-antibody test can detect the virus in 18 to 90 days.

- Nucleic acid tests detect the actual virus in the blood. They can detect HIV within 10 to 33 days after exposure. They are used as a confirmatory test after an antibody or antibody-antigen test or when someone has a recent exposure and a negative antibody or antibody-antigen test.

In addition to testing in healthcare settings, self-testing, testing of self-collected samples, and testing in nonclinical or community settings are vital tools to make testing easy and accessible to individuals in various mental, social, or geographic contexts. Often paired with other HIV prevention services or STI testing, testing in nonclinical settings can be an effective means of bringing testing to people who may otherwise not get tested, particularly those who are highly stigmatized and at high risk. Research shows that MSM who use take-home tests tested themselves more frequently, identified more infections, did not increase risky sexual behaviors, and shared their results with their social networks, raising others' awareness of their HIV infection.[CDC. HIV Self-Testing. 2023]

Improving Access to Quality HIV Prevention and Care Services

Sufficient and stable funding for HIV programming is of critical importance, influencing the availability and penetration of interventions, particularly in low- and middle-income countries.[36] Indeed, in areas of Africa where funding has supported widespread testing and treatment paired with a variety of patient-centered measures tailored to at-risk populations, population-level viral suppression has exceeded that of the United States.[24] By 2019, Eswatini, Namibia, and Rwanda exceeded the UNAIDS target of 73% viral suppression across all HIV-positive people.

On the other hand, the full range of HIV medications, given as PrEP, PEP, or TasP as recommended by the WHO, is not available in all countries, limiting the quality and effectiveness of HIV prevention efforts. For example, recommendations for PrEP have not been adopted in national guidelines in Russia, China, Angola, Libya, Sudan, and Venezuela, amongst others.[WHO. HIV Policy Adoption Fact Sheet. 2023] The addition of PrEP to locally available prevention measures is necessary to end global transmission of HIV, particularly in areas with a high burden of HIV.[37]

Putting patients at the center allows maximum benefit from TaSP, PrEP, and other prevention measures and improved clinical and public health outcomes.[WHO. People-Centred Health Services. 2016][WHO. Men and HIV Interventions. 2023]. For example, due to its ease of use for those facing barriers to regular, daily medication use, cabotegravir may be ideal for PrEP. To improve patient-centered care, the WHO recommends linking strategies and treatment of related diseases or syndromes, such as in its strategy for HIV, viral hepatitis, and STIs.[WHO. Global Health Sector HIV Strategies. 2022] Important patient-centered outcomes such as self-image can be improved, and self-stigma can be reduced through interventions such as TasP, in addition to more standard outcomes such as increased testing, adherence to therapy, and viral suppression.[22]

Systems, sectors, and partnerships must be optimized for impact. Strategies and programs should be based on a cohesive theoretical change model addressing individual behavioral, provider, and institutional barriers to coordinate care activities across sectors, ensure consistent implementation, and achieve desired outcomes. A growing body of public health intervention research on the influence of social and structural determinants of health, intersectionality, and patient-centered interventions helps to guide quality improvement measures for the prevention of HIV.

Including communities and civil society in advocacy, service delivery, and policy-making ensures that services are culturally appropriate and responsive to the needs of the population it serves. For example, partnering with community organizations has been shown to improve linkage to care for HIV treatment, decreasing the time to viral suppression and reducing the risk of HIV transmission.[38] When implemented broadly in locally defined at-risk populations, the use of PrEP as prescribed has a powerful influence on reducing incident HIV transmission at the population level. Community-level interventions, such as door-to-door HIV prevention services, are beneficial in areas of high prevalence, such as urban areas with high levels of poverty.[CDC. HIV - Communities in Crisis. 2019]

A clear understanding of the social context in which HIV infection occurs is vital to providing high-quality programming.[23] For example, while TasP use has increased over time, particularly among MSM, its optimal use is hampered by disbelief that U=U among people who do not have HIV and those living in Africa. Acceptability is high once the science is understood.[22] HIV care and prevention models that address the overlapping clinical and social complexities faced by many equity-deserving populations can lead to better clinical outcomes. Structural interventions to improve socioeconomic conditions may also reduce HIV infection rates.[CDC. HIV - Communities in Crisis. 2019]

Stigma is a significant societal barrier that limits access to quality service and must be addressed. Specialist or targeted clinics for HIV care may best serve people who experience a high degree of stigma, including people who are Indigenous or transgender, inject drugs, or sell sex, and those at risk due to multiple factors. While research shows comprehensive SSPs for PWID to be safe, effective, cost-effective, and an important factor in reducing the transmission of viral hepatitis, HIV, and other infections, these programs are not offered or face regulatory restrictions in many areas.[CDC. Syringe Services Programs (SSPs). 2023]

Monitoring, Surveillance, and Reporting

Monitoring, surveillance, and reporting are essential to improve access to quality services, respond to outbreaks, and determine progress toward HIV prevention goals across various populations. In collaboration with local or state public health authorities, clinicians can contribute to these efforts by fully completing reporting forms where required and participating in efforts to streamline and improve surveillance.

In 2014, UNAIDS proposed a set of global "90-90-90" HIV prevention targets for 2020.

- 90% of all people living with HIV will know their HIV status.

- 90% of all people with diagnosed HIV infection will receive sustained ART.

- 90% of all people receiving ART will have viral suppression.

Adoption by the United Nations General Assembly committed member countries to these targets via a Political Declaration on HIV and AIDS. In 2021, UN member states adopted ambitious yet achievable 95-95-95 targets for 2025 based on data demonstrating good progress across countries, advances in therapeutic options and implementation science, and new insights into inequities.[36]

The National HIV/AIDS Strategy [US Gov. National HIV/AIDS Strategy. 2023] and the Ending the HIV Epidemic in the U.S. initiative aims to reduce new HIV transmissions in the United States by 90% by 2030, prioritizing the reduction of HIV-related health disparities and health inequities and improving well-being for people who live with HIV.[CDC. Ending the HIV epidemic. 2023]

The WHO and country and state disease control and prevention centers, such as the US CDC, are primary data sources for monitoring HIV trends and progress toward goals. Behavioral and clinical characteristics of adults diagnosed with HIV infection are followed in the United States by the Medical Monitoring Project. Instituted in 2005, it is a cross-sectional, nationally representative, complex sample survey.[CDC. HIV Surveillance Report 2021 Cycle. 2023] The CDC's AtlasPlus allows practitioners to explore national HIV, hepatitis, STI, and tuberculosis data relevant to their population.[CDC. NCCHHSTP AtlasPlus. 2023] All data from 2020 and 2021 must be interpreted in the context of decreased case surveillance and access to HIV services during the COVID-19 pandemic.[CDC. HIV Basic Statistics. 2023]

Research and Innovation

Research and innovation are crucial to accelerating the impact of HIV prevention measures. Improved HIV diagnostic technologies and new ARTs have been and continue to be active areas of research since the HIV virus was first identified in 1984. As the world reaches toward the 95-95-95 goals, implementation research determining the best interventions for specific contexts or populations that continue to experience higher rates of HIV has become increasingly important.[22]

- Who delivers the intervention, eg, peer advocates, pastors, or nurses

- Where the intervention is delivered, eg, clinic, community event, or rural community

- Which theoretical change pathway is targetted, eg, self-image, altruism, or stigma

- How testing and treatment are best linked, eg, physician referral processes, health navigators

- Impacts on HIV treatment indicators, eg, viral suppression, the incidence of STIs, or retention in care

HIV preventive and therapeutic vaccine research has likewise been ongoing since the 1980s. To date, a successful vaccine has been elusive. A genetic basis for HIV acquisition has been identified, providing a novel potential for a possible cure. A case study reported in 2019 described an individual with HIV-1 who underwent allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for Hodgkin lymphoma using cells from a donor with a homozygous mutation in the HIV coreceptor CCR5 (CCR5Δ32/Δ32) maintained HIV remission without the need for HIV therapy.[39] ART was stopped 16 months after transplantation, with HIV-1 remission maintained over an 18-month follow-up after cessation.