Introduction

The basal ganglia is a cluster of nuclei found deep to the neocortex of the brain. It has a multitude of functions associated with reward and cognition but is primarily involved in motor control. In particular, the basal ganglia is considered to be a gate-keeping mechanism for the initiation of motor movement, effectively choosing which actions to allow and which actions to inhibit. In addition, nuclei of the basal ganglia project to limbic and prefrontal regions of the thalamus and cortex and function in a similar way to manifest executive decision-making and reward or aversion emotional stimulation. A number of landmark motor disorders affect the basal ganglia such as Parkinson and Huntington disease which disturb motor control in markedly different contexts.

Structure and Function

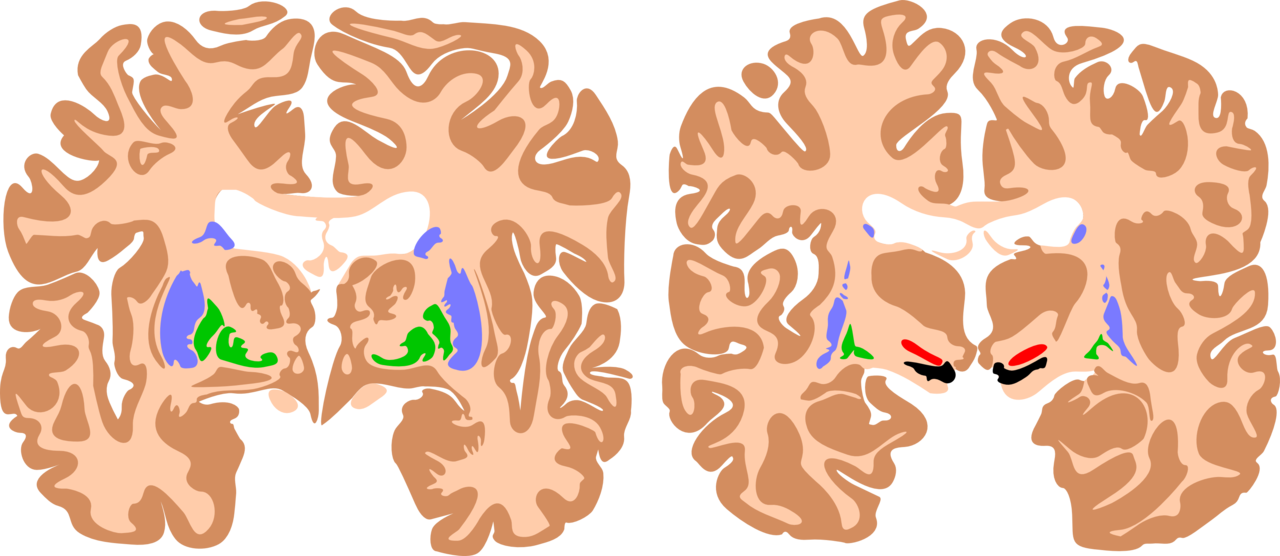

The basal ganglia are a cluster of subcortical nuclei deep to cerebral hemispheres. The largest component of the basal ganglia is the corpus striatum which contains the caudate and lenticular nuclei (the putamen, globus pallidus externus, and internus), the subthalamic nucleus (STN), and the substantia nigra (SN). These structures intricately synapse onto one another to promote or antagonize movement.

The largest subcortical brain structure of the basal ganglia is the striatum with a volume of approximately 10 cm.[1] Within the striatum, there are two main divisions, the dorsal striatum, and the ventral striatum. The dorsal striatum is primarily involved in control over conscious motor movements and executive functions, while the ventral striatum is responsible for limbic functions of reward and aversion. Of the dorsal striatum, the caudate nucleus is a C-shaped structure comprising a head, body, and tail located lateral to the lateral ventricles. The lenticular (or “lens-shaped”) nuclei are bounded medially by the caudate and thalamus and laterally by the external capsule. The anterior end of the lenticular nuclei is continuous with the head of the caudate. The lenticular nuclei subdivide into the putamen and globus pallidus, which further divides into an external (GPe) and internal (GPi) segments. The striatum receives input signals from the cortex and limbic system and deep gain-setting nuclei of the brainstem (such as the substantia nigra, or SN). The dorsal striatum has GABAergic projections from medium spiny neurons onto either the GPi (called the “Direct pathway”) or the GPe (called the “Indirect pathway”) (See Figure). The ventral striatum is composed of the nucleus accumbens and the olfactory tubercle and has similar output pathways to the globus pallidus while receiving input from other gain-setting nuclei (such as the ventral tegmental area).

The subthalamic nucleus (STN), located ventral to the thalamus, receives many different projections from the cortex, GPe, SN, and the pontine reticular formation. It sends glutaminergic projections to GPi and substantia nigra. However, relative to disorders of motor movement, the primary pathways involved are the inhibitory, GABAergic projections from the GPe, and the STN’s excitatory glutamatergic projections to the GPi. These projections form the main circuitry of the “Indirect pathway” of the basal ganglia.

The substantia nigra is composed of two distinct nuclei, the inhibitory pars reticulate (SNpr) and the dopaminergic pars compacta (SNpc). These nuclei are situated in the midbrain lying dorsal to the cerebral peduncles. The substantia nigra derives its name from its dark, neuromelanin pigment formed along the same biosynthetic pathway as dopamine. These dopaminergic neurons of the SNpc receive inputs through the ascending reticular activating system, a deep network of brainstem nuclei, and ascending collaterals that regulate alertness and prime automatic functions prior to cortical awareness and are a way of refining or preselecting appropriate motor, executive, limbic and autonomic responses.[2] The dopaminergic projections of the SNpc synapse on the putamen and the caudate nuclei of the striatum. The SNpr sends inhibitory axons to the ventral anterior (VA) and ventrolateral (VL) nuclei of the thalamus.

The basal ganglia’s primary function is to control conscious and proprioceptive movements. It receives signals from the cortex, weighs those signals, and determines what actions to “disinhibit”.[3] To understand the circuitry required in the basal ganglia, its nuclei must be divided into input nuclei, output nuclei, and intrinsic nuclei. The primary input nuclei to the striatum are dopaminergic inputs from the SNpc as well as excitatory inputs from the cortex and the intralaminar thalamic nuclei. The primary output from the striatum is the GPi/SNpr. The GPi and SNpr complex send inhibitory projections onto the VA and VL of the thalamus. The SNpr also synapses on the superior colliculus, pedunculopontine nucleus, and medullary reticular formation to modulate awareness and attention.

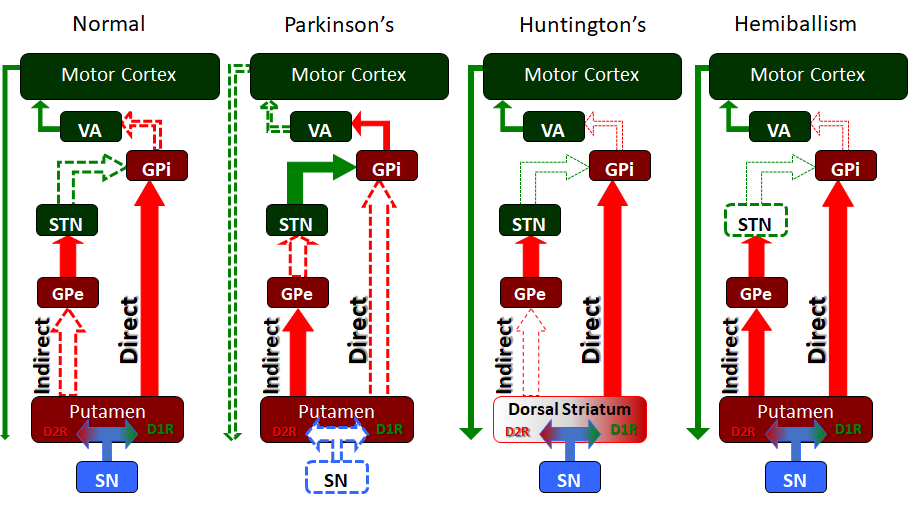

Finally, the intrinsic nuclei of the striatum communicate via the “Direct pathway” and “Indirect pathway” which are the classic elements of the intrinsic basal ganglia circuitry. These two pathways work in opposition to one another to allow for the weighing and choosing of motor movements. Within the intrinsic nuclei of the dorsal striatum, there exist two main populations of neurons, neurons that are excited by dopamine and which express the D1-family of dopamine receptors, and neurons that are inhibited by dopamine and which express the D2-family of dopamine receptors. The neurons that express the D1-family of receptors send projections to the GPi/SNpr to form the “Direct pathway” while those expressing D2-family of receptors send projections to the GPe as part of the “Indirect pathway.”

The “Direct pathway” is comprised of inhibitory projections from the caudate or putamen. Activity in the “Direct pathway” releases or “disinhibits” motor movement by inhibiting the GPI/SNpr. Dopamine, via the nigrostriatal pathway, synapses on striatal neurons that express the D1-family of receptors. The excited D1R neurons send inhibitory projections to inhibit the GPi/SNpr. The GPi/SNpr has GABAergic inhibitory neurons that project to the VA and VL of the thalamus both of which send excitatory projections to the motor cortex. In this way, the “Direct pathway” inhibits the GPi which in turn is no longer inhibiting the VA and VL of the thalamus. As a result, the VA/VL are said to be “disinhibited” and can excite the motor cortex to promote movement through its corticospinal projections.

The “Indirect pathway” inhibits motor activity. The dorsal striatal neurons expressing the D2-family of dopamine receptors are inhibited by dopamine from the SN. These D2R neurons send inhibitory GABAergic connections to the GPe. The GPe inhibits the subthalamic nucleus, which excites the GPi/SNpr, completing the “Indirect pathway.” As mentioned above, the GPi sends inhibitory GABAergic signals to the VA and VL of the thalamus. In this way, the activation of the “Indirect pathway” results in stimulation of the GPi which then inhibits the VA/VL of the thalamus, ultimately inhibiting movement.

An experiment using a Cre-dependant viral expression suggested that the direct and indirect pathways work together when moving. However, upon resting, both pathways are not utilized as much. This supports the continued approach that the direct and indirect pathways work in conjunction rather than opposing each other. New advances such as optical measurement of neuroactivity florescent will continue to segue into understanding how the two pathways work with each other.[4]

The nigrostriatal pathway serves as a basal ganglia input and modulates the direct and indirect pathways. The substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) sends dopamine to the striatum via this pathway. As mentioned, the striatum has a population of neurons that are excited by dopamine because they express the D1-family of dopamine receptors as part of the “Direct pathway.” Therefore, dopamine will depolarize this population of striatal neurons and increase activity in the “Direct pathway.” The striatum also has a population of neurons, the “Indirect pathway” which are inhibited by dopamine as they express the D2-family of dopamine receptors. Dopamine will hyperpolarize this population and inhibit the “Indirect pathway.” Thus the SNpc amplifies the response of the basal ganglia by exciting the direct and inhibiting the indirect. A tonic release of dopamine preferentially modulates the D1 receptor, and this is a powerful modulator of the nigrostriatal pathway.[5]

The corticostriate (and corticosubthalamic) pathways are cortical projections that input on the striatum, including the caudate and putamen.[3] These excitatory glutamatergic projections from layers III and V of the cortical lobes, including the motor, frontal, and parietal lobes provide the basal ganglia with information about conscious intentions to weigh with the deep, automatically triggered inputs from the SNpc which unconsciously constrain or enhance signals for certain outputs. Because the basal ganglia nuclei or consistently somatotopically organized,[6] current thinking is that multiple input signals are required within the basal ganglia in order to “disinhibit” or “release” the functions that are receiving the most stimulatory and least inhibitory signals from the corticostriate and nigrostriatal pathways, as weighed by the basal ganglia.[7]

Embryology

The basal ganglia develop with the neural tube. The basics of neural tube development begin with the notochord inducing the ectoderm to become neuroectoderm. This subsequently develops into a neural plate. The neural plate has neural grooves that fold and fuse to become the neural tube. The primary vesicle is the forebrain vesicle, known as the prosencephalon. The prosencephalon then developed into telencephalon, eventually giving rise to the basal ganglia.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Blood supply to the basal ganglia is primarily supplied by the lenticulostriate arteries, which are branches of the middle cerebral artery. Note that the lenticulostriate arteries are prone to hemorrhage in patients with uncontrolled hypertension.

Surgical Considerations

The putamen is considered to be the most common site of intracerebral hemorrhage secondary to systemic hypertension. Surgical evacuation of such bleeds is still a topic of debate. Open craniotomy and endoscopic methods have been used to evacuate such bleeds in indicated cases.[8]

Clinical Significance

Parkinson Disease

Parkinson disease is perhaps the most notorious disease of the basal ganglia. Classic clinical symptoms include bradykinesia, resting tremor, postural instability, and shuffling gait. This disease is a result of neurodegeneration of the SNpc dopaminergic neurons. Often found in the Parkinsonian striatum, alpha-synuclein protein aggregates form toxic “Lewy bodies,” which are inclusions within neurons. The substantia nigra, due to degeneration, loses its grossly visible dark pigmentation, a concomitant sign of dopamine biosynthesis dysfunction. This loss of dopamine depresses the nigrostriatal pathway. With decreased dopaminergic input the striatum exerts less positive motor activity and more negative motor inhibition. This gives the characteristic hypokinetic dysfunction found in these patients. Treatment is levodopa, a precursor to dopamine. This is an attempt to replace the loss dopamine in the substantia nigra.[9] The trigger of this loss of dopaminergic neurons is often unknown but can be multivariable, as a variety of toxins, metabolic, and physiological stressors have been implicated as well as some genetic mutations.[10]

Huntington's Disease

Huntington's disease is a hyperkinetic movement disorder. Its cause is a genetic defect manifesting as a CAG repeat on chromosome 4p on the HTT gene. This creates an abnormally long Huntington gene which leads to neuronal death in the caudate and the putamen. The indirect pathway is interrupted and leads to a hyperkinetic presentation. Symptoms include involuntary movements such as chorea, cognitive degeneration, and psychiatric dysfunction. Treatment is tetrabenazine which is a vesicular monoamine transporter inhibitor. It inhibits monoamine (serotonin, dopamine, norepinephrine) uptake into synaptic vesicles. This reduces the intense stimulation of the striatum from the nigrostriatal pathway. While no cure for Huntington disease exists, tetrabenazine and reserpine are palliative medicines that decrease the disease symptoms.

Hemiballism

Hemiballism (from the Greek “to throw”) is used to describe hyperkinetic, involuntary, forceful movements of the ipsilateral arm and leg. Commonly, a lesion in the contralateral subthalamic nuclei causes hemiballism. Given that the subthalamus is part of the indirect pathway this lesion reduces or eliminates indirect pathway signaling, leading to a relative overabundance of activity in the direct pathway. Such causes include stroke, traumatic brain injury, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, nonketotic hyperglycemia, neoplasm, vascular malformation, and other causes. Ballism, a bilateral version of hemiballism, can rarely occur in an overdose of levodopa.[11]

Tourette Syndrome

Tourette syndrome has been shown to have a significant neurological basal ganglia component which manifests as sudden, repetitive uncontrolled movements and vocalizations, called “tics.” These tics have been associated with dysfunction of the GABAergic projections from the striatum, leading to a relative increase in dopaminergic activity much like in hemiballism and Huntington’s disease.[12]