Continuing Education Activity

Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) is an autosomal dominant disorder of lipid metabolism presenting at birth. It is characterized by very high low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels causing premature coronary heart disease. The majority of cases are undiagnosed and suboptimally treated. Early diagnosis and appropriate treatment are important in preventing premature death. This activity examines when this condition should be considered on differential diagnosis and how to properly evaluate for it. This activity highlights the role of the interprofessional team in diagnosing and managing patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Describe the etiologic factors associated with the development of familial hypercholesterolemia.

- Summarize the evaluation for familial hypercholesterolemia.

- Describe the treatment considerations for patients with familial hypercholesterolemia.

- Explain modalities to improve care coordination among interprofessional team members in order to improve outcomes for patients affected by familial hypercholesterolemia.

Introduction

Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) is an autosomal dominant disorder of lipid metabolism. It is characterized by very high low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels due to a gene mutation causing premature coronary heart disease. Homozygous individuals typically acquired disease in childhood. The majority of cases are undiagnosed and sub-optimally treated. Early diagnosis and appropriate treatment are essential in preventing premature death.[1][2][3][4]

Etiology

Genetic disorders with high LDL-C are most commonly caused by autosomal dominant conditions and rarely inherited as a recessive trait. Mutations in the LDL receptor (LDLR; “classic FH”) cause 80% to 90% of cases of clinical FH and have an autosomal dominant inheritance. Rarely, mutations in APOB and PCSK9 can cause autosomal dominant hypercholesterolemia. However, the clinical phenotype cannot distinguish between these three mutations.[1]

APOB synthesizes the major protein in LDL, which is the ligand for LDLR. A mutation resulting in defective ApoB-100 results in impaired binding of LDL particles to LDLR and thus impaired clearance.

PCSK9 synthesizes a circulatory protein that limits LDL receptor lifespan. Therefore, gain-of-function mutation results in FH.[5]

Over 1600 mutations in the LDLR causing classic FH have been identified. Mutations can be homozygous or heterozygous. True homozygotes have the same mutation in both alleles, whereas compound heterozygotes have different mutations in each allele. Compound heterozygotes have a similar phenotype to homozygous FH.

Patients with less than 2% of LDLR activity are classified as receptor-negative, and patients with two to 5% of regular LDLR activity are classified as receptor defective.

It is important to note that about 30 to 50% of patients with FH phenotype do not have an identifiable gene defect. Thus, gene testing is not a requisite for the diagnosis, which is, in most cases, clinical.FH caused by a de novo mutation is very rare, and therefore, documenting detailed family history is very important.[6]

Epidemiology

Heterozygous FH (HeFH) is the most common monogenic, autosomal dominant disorder in humans. It occurs in approximately one in 300 people. Homozygous FH (HoFH) has a prevalence of one in 160,000 to 500,000 people. The prevalence is 18 times higher in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and almost 21 times higher in patients with premature ischemic heart disease. The prevalence of FH is higher in Dutch Afrikaners, French Canadians, Ashkenazi Jews, Christian Lebanese, and some Tunisian groups. There is a “gene dosing effect,” and homozygotes are more severely affected than heterozygotes.[7]

Pathophysiology

Familial hypercholesterolemia is a disorder that results from absent or defective low-density lipid-protein (LDL) receptors. The LDLR gene is located on the short arm of chromosome 19, and the LDLR is comprised of 860 amino acids. The LDLR is primarily responsible for hepatic uptake of LDL, which constitutes about 70% of circulating LDL. Two ligands, apolipoprotein B-100, and apo-E bind to the receptor.

The normal number and function of LDL receptors in the liver are important for the uptake of LDL cholesterol. Receptor-negative FH patients have less than 2%, and receptor-defective patients have about 2% to 25% of normal LDLR activity.

There are five different classes of alleles based on the phenotypic behavior of mutant protein that results from mutations at the LDLR locus. These are as follows:

- Class I: Null, synthesis of LDLR is defective

- Class II: Transport defective, intracellular transport from the endoplasmic reticulum to Golgi apparatus is impaired.

- Class III: Binding defective, binding of LDL protein to the receptor is defective.

- Class IV: Internalization defective, proteins can bind normally, but receptors do not internalize LDL proteins do too ineffective clustering in the coated pits

- Class V: Defective recycling, dissociation of the receptor and like and is interrupted, thereby interrupting recycling of the receptor.[8]

Reduced or absent uptake of LDL cholesterol by the liver leads to very high LDL cholesterol levels from birth with resultant premature atherosclerosis, critical aortic stenosis, and coronary artery disease (CAD).

Homozygous FH patients often have untreated LDL-C levels above 500 mg/dL, but lower levels do not rule out HoFH. HoFH causes severe CAD by the first and second decade of life. Heterozygotes are also at increased risk of CAD between 30 to 60 years of age. Stroke is uncommon. Xanthomas, which are yellowish patches of cholesterol build-up due to extremely high levels of LDL-C, can occur around eyelids (xanthelasma), within tendons of the elbows, hands, knees, and feet. A thickened Achilles tendon should raise a high level of suspicion for HoFH. The prevalence of xanthomas increases with age. Another diagnostic sign on the physical exam is corneal arcus which is a white, gray, or blue opaque ring around the corneal margin when seen in individuals younger than 45 years of age.[8][6][9][10]

History and Physical

Detailed personal and family history and a physical exam are important for making the diagnosis. Particular attention should be paid to atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases (ASCVD) such as angina, prior myocardial infarction, arterial revascularization, transient ischemic attack, stroke, or claudication. Eliciting a history of other major risk factors for ASCVD is important, such as hypertension, smoking, obesity, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease. The physical exam should look for tendon xanthomas, xanthelasma, corneal arcus, evaluation of pulses of major arteries, and signs of aortic stenosis.[11]

Evaluation

It is important to exclude secondary causes of hypercholesterolemia such as hypothyroidism, nephrotic syndrome, and liver disease by history and laboratory testing. Diagnosis of FH in most cases is:

- Clinical, by a personal history of early CAD, family history of premature CAD (definite MI or sudden death, at an age younger than 55 in male first-degree relative or younger than 65 in a first-degree female relative)

- Physical exam findings (tendon xanthomas and premature corneal arcus)

- Elevated lipid levels (LDL-C greater than 190 mg/dL)

In the past, the diagnosis was usually made at the time of an acute MI in a young person. However, it is now most commonly found by routine lab testing that reveals elevated LDL-C, which leads to clinical suspicion. Triglyceride levels are characteristically normal, and HDL levels might be low. It is important to emphasize that any LDL-C level greater than 190 mg/dL should trigger an investigation for HeFH or HoFH.

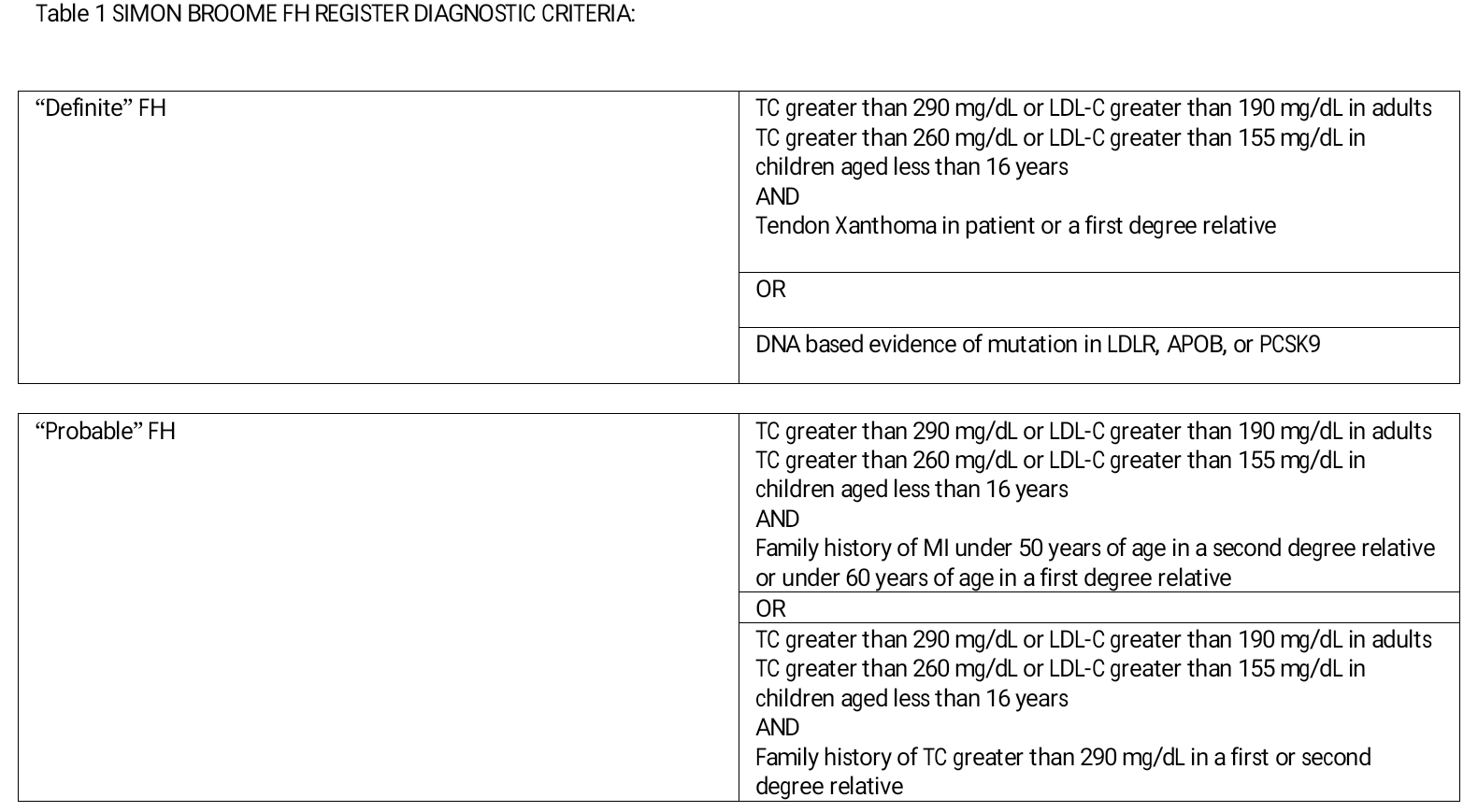

The diagnosis of FH in most cases is made phenotypically. Available clinical tools to make the diagnosis of FH are the Dutch Lipid Clinic Network criteria, Simon Broome criteria (Table 1), Make Early Diagnosis to Prevent Early Deaths (MED-PED) criteria, and Japanese FH criteria.[11][7]

Detection of index cases could be done by targeted screening of individuals with premature CVD, opportunistic screening in primary care based on age and gender-specific plasma LDL-C levels, or universal screening based on age and gender-specific plasma LDL-C levels before the age of 20 years and ideally before puberty. Children with xanthomata or other physical findings of FH or suspected to have HoFH by family history should be screened at 2 years of age. Children suspected to have HeFH should be screened between the ages of 5 and 10 years. It is recommended that two fasting LDL cholesterol values are obtained in children and adolescents. A high probability of FH is indicated by LDL of greater than or equal to 155 mg/dL or greater than or equal to 135 mg/dL with a parental history of hypercholesterolemia or premature CHD.

Testing should not be done during acute illness because it can lower LDL-C levels leading to false-negative testing. If already on statin therapy, it is important to look at pre-treatment values of LDL-C. If not available, the LDL-C level should be estimated based on the dose of the specific statin.

Cardiovascular risk assessment tools such Framingham risk score should not be used as FH is a lifetime coronary risk equivalent.

In asymptomatic patients with FH, cardiac CT and carotid ultrasound may be useful for stratifying risk and needs further studies.

Criteria for the clinical diagnosis of homozygous FH include:

Untreated LDL-C >500 mg/dL (>13 mmol/L) or treated LDL-C ≥300 mg/dL (>8 mmol/L), AND

- Cutaneous or tendon xanthoma before ten years of age, OR

- Elevated LDL-C levels consistent with heterozygous FH in both the parents

It is important to note, however, that untreated LDL-C levels <500 do not exclude homozygous FH, particularly in young children.[11]

Treatment / Management

It is important to advise patients on lifestyle modifications and to correct all modifiable non-cholesterol risk factors. A healthy diet, exercise therapy, smoking cessation, and management of obesity constitute important lifestyle management of the disease.Pharmacological options as adjuncts to lifestyle modification for achieving these goals include high-intensity statin therapy, ezetimibe, bile acid sequestrants, niacin, and fibrates. Statins are first-line drugs for the management of FH but may be ineffective in HoFH as they are dependent on increasing LDLR expression for LDL-C lowering.

LDL-C levels are the primary target for treatment in FH patients. Starting with high-intensity statins in FH adults and adding ezetimibe or other therapies when treatment targets are not reached is recommended. In adults, the goal for LDL-C therapy will be at least 50% reduction, followed by LDL-C less than 70 mg/dL (no CHD or other major risk factors), or less than 55 mg/dL (in the presence of CHD or other major risk factors). In many cases, it is difficult to achieve these targets. In children with FH, between the ages of 8 and 10 years, after the institution of dietary changes, if LDL-C is greater than 155 mg/dL on two occasions, low dose statin monotherapy should be considered for an LDL-C target of less than 155 mg/dL. In children with FH, above the age of 10, after the institution of dietary changes, if LDL-C is greater than 135 mg/dL on two occasions, statin monotherapy should be considered for an LDL-C target of less than 135 mg/dL, with the addition of ezetimibe or bile acid sequestrant if required.

Pharmacological options as adjuncts to lifestyle modification for achieving these goals include high-intensity statin therapy, ezetimibe, bile acid sequestrants, niacin, and fibrates. Statins are first-line drugs for the management of FH but may be ineffective in HoFH as they are dependent on increasing LDLR expression for LDL-C lowering. In HeFH, statin monotherapy can reduce LDL-C up to 30% to 60%, and an additional 20% to 30% lowering can be achieved by combination therapy. Lipid-lowering with statin-based regimens has been shown to improve survival and reduce morbidity significantly. PCSK9 inhibitors can be useful as long as some LDLR function is present; the FDA approves alirocumab and evolocumab for use in adult patients with HeFH or clinical ASCVD requiring additional LDL-C lowering as an adjunct to diet and maximally tolerated statin therapy. Evolocumab is currently FDA-approved for HoFH as an adjunct to diet and other LDL-C lowering therapies.[12]

The presence of other ASCVD risk factors will necessitate greater intensity of medical management. Although evidence for combination therapies for the prevention of ASCVD events is lacking, strict management of LDL-C levels is recommended in patients with FH.

HoFH is less responsive to drug therapy than HeFH. Thus LDL-C apheresis (LA) has been developed as a primary management strategy. Additional options for patients with HoFH include the microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (MTP) inhibitor, lomitapide, and the apoB antisense oligonucleotide (ASO), mipomersen, especially when LA is not available. Due to their mechanism of action, these drugs do not depend on LDLR expression for LDL-C lowering.

In women of childbearing potential, counseling on contraception before starting a statin and pre-pregnancy counseling is important. Statin therapy should be discontinued three months before planned conception and should not be used during pregnancy or breastfeeding. Lipid-lowering therapy other than bile acid sequestrants (Class B for pregnancy) should not be used during pregnancy. LDL apheresis has been safely used during pregnancy and is especially useful in patients with established CAD.

LDL-C apheresis as an adjunct to diet and maximally-tolerated drug therapy should be considered in all patients with HoFH or compound HeFH, in HeFH with CHD not achieving LDL cholesterol targets on maximal drug therapy or in the setting of statin intolerance. In children with HoFH, LA should be considered before the age of 5 and not later than eight years. LA sessions typically last 2 to 4 hours and are done on a weekly or bi-weekly schedule at apheresis centers. It decreases LDL and Lp (a) levels by 50% to 75%, and over 1 to 2 weeks, levels tend to return to baseline. During chronic use of LA, LDL and Lp (a) levels may be reduced by 20% to 40%. FDA-approved indications for LA are LDL-C greater than 300 mg/dL on maximally tolerated therapy, and in the presence of CAD, LDL-C greater than 200 mg/dL on maximally tolerated therapy. Cost and access to LA are barriers, thus limiting options in the effective management of patients with homozygous FH.Orthotopic liver transplantation is considered for younger patients with HoFH with rapid progression of atherosclerosis or aortic stenosis if they are not able to tolerate LA or have inadequate LDL-C lowering with LA, diet, and medications.[13][14]

Differential Diagnosis

In the differential diagnosis of hypercholesterolemia and premature atherosclerosis, familial combined hyperlipidemia, hyperapobetalipoproteinemia, familial dysbetalipoproteinemia, and polygenic hypercholesterolemia should be considered.[15]

The other causes of tendon xanthomas and premature atherosclerosis include rare genetic disorders such as sitosterolemia and cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis.[16]

Prognosis

The prognosis of patients with familial hypercholesterolemia is worse than those without this disease at any level of untreated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Patients with acute coronary syndrome and a history of heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia treated with high dose statins have three times the highest risk of death and nonfatal myocardial infarction within one year when compared to matched individuals without familial hypercholesterolemia.

Complications

Premature coronary artery disease and a thorough sclerotic cardiovascular disease are major complications that can lead to severe morbidity and mortality. Other complications include xanthelasmas and corneal arcus.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Children should be encouraged to eat healthy foods to eat more vegetables and fruits and less junk food. Moreover, they should have a screening lipid profile at the age of 9 to 11 and again around age 17 to 21. However, some children may get tested earlier if they have a parent with familial hypercholesterolemia or if they have signs of FH, such as xanthomas.Women of childbearing age should be explained about the risks of taking statin during pregnancy. They should stop taking statins at least three months before trying to conceive.Patients should be encouraged to eat minimum lipids in their diet, and for this reason, they should be referred to a dietitian and nutritionist or lipid specialist that can help them follow a better diet plan.

Pearls and Other Issues

Cascade screening is a cost-effective, evidence-based intervention, starting with first-degree relatives of patients with FH by cholesterol screening with or without genetic testing. The use of genetic testing in cascade screening improves the detection rate of FH. Cascade screening can lead to early diagnosis and institution of therapy for FH resulting in ASCVD reduction. National and international organizations have recommended cascade screening for FH. Concerns regarding privacy require that the patient with FH make the first contact with family members. For patients diagnosed with FH, the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act protects against health insurance and employment discrimination.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis and management of familial hypertriglyceridemia require an interprofessional team that includes an endocrinologist, lipid specialist, primary care provider, nurse practitioner, gastroenterologist, cardiologist, internist, nutritionist, and a pharmacist. Besides pharmacological treatment in conjunction with a board-certified cardiology pharmacist consulting with clinical staff, it is important to advise patients on lifestyle modifications and to correct all modifiable non-cholesterol risk factors. A healthy diet, exercise therapy, smoking cessation, and management of obesity are important.

In women of childbearing potential, counseling on contraception before starting a statin and pre-pregnancy counseling is important. Nursing staff can have involvement in this monitoring and counsel and inform the clinician of any changes in status. Statin therapy should be discontinued three months before planned conception and should not be used during pregnancy or breastfeeding. Lipid-lowering therapy other than bile acid sequestrants (Class B for pregnancy) should not be used during pregnancy. LDL apheresis has been safely used during pregnancy and is especially useful in patients with established CAD.

Orthotopic liver transplantation is considered for younger patients with HoFH with rapid progression of atherosclerosis or aortic stenosis if they are not able to tolerate LA or have inadequate LDL-C lowering with LA, diet, and medications.