Continuing Education Activity

The most common type of fracture in the pediatric population is elbow fractures. Most commonly, individuals fall on their outstretched hand. Prompt assessment and management of elbow fractures are critical, as these fractures carry the risk of neurovascular compromise. Supracondylar fracture is the most common fracture in children under seven years, and these constitute approximately 15% of all pediatric fractures. The peak incidence occurs at around 6 years of age, with a male predominance. However, there are many other variants of elbow fractures. This activity reviews the etiology, presentation, evaluation, and management of various types of elbow fractures, and reviews the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating, diagnosing, and managing the condition.

Objectives:

- Identify the most commonly seen varieties of elbow fractures and describe their particular mechanism and pathophysiology.

- Describe a complete workup and examination for the elbow, when presented with a possible elbow fracture.

- Review the various treatment options for elbow fractures based on the type of fracture.

- Summarize the importance of collaboration and communication among the interprofessional team members to improve outcomes for patients affected by elbow fractures.

Introduction

The most common type of fracture in the pediatric population is elbow fractures. Most commonly, individuals fall on their outstretched hand. Prompt assessment and management of elbow fractures are critical, as these fractures carry the risk of neurovascular compromise. The following are the types of elbow fractures in pediatrics:

Supracondylar Fractures

This type of fracture involves the distal humerus just above the elbow. It is the most common type of elbow fracture and accounts for approximately 60% of all elbow fractures. It is considered an injury of the immature skeleton and occurs in young children between 5 to 10 years of age. Based on the mechanism of injury and the displacement of the distal fragment, professionals classify these as either extension or flexion type fractures.[1][2][3]

In an extension type of fracture, which happens more than 95% cases, the elbow displaces posteriorly. The typical mechanism is falling on an outstretched hand with the elbow in full extension. An example is falling from monkey bars. Beware that a nondisplaced fracture may be subtle and may only be recognized by one of the following:

- Posterior fat pad sign

- Anterior sail sign

- Disruption of the anterior humeral line

Radiographically, these fractures are classified into three types:

- Type I: minimal or no displacement

- Type II: displaced fracture, posterior cortex intact

- Type III: totally displaced fracture, anterior and posterior cortices disrupted

In a flexion type fracture that happens in less than 5% of cases, the elbow is displaced anteriorly. The typical mechanism is when a direct anterior force is applied against a flexed elbow, which causes anterior displacement of the distal fragment. With the displacement of the fragment, the periosteum tears posteriorly. Since the mechanism is a direct force, flexion type fractures are often open.[4][5][6][7]

- Type I fracture: non-displaced or minimally displaced

- Type II fracture: incomplete fracture; anterior cortex is intact

- Type III fracture: completely displaced; distal fragment migrates proximally and anteriorly

One of the most serious complications is neurovascular injury following the fracture, as the brachial artery and median nerve are located close to the site of fracture and can be easily compromised.

Gartland Classification

Supracondylar fractures can be classified depending on the degree of displacement:

- Gartland Type 1 Fracture: Minimally displaced or occult fracture. The fracture is difficult to see on x-rays. The anterior humeral line still intersects the anterior half of the capitellum. The only visible sign on an x-ray will be a positive fat pad sign.

- Gartland Type 2 Fracture: Fracture that is displaced more posteriorly, but the posterior cortex remains intact.

- Gartland Type 3 Fracture: Completely displaced fracture with cortical disruption. Posteromedial displacement is more common happening in 75% of cases compared to posterolateral displacement which occurs in 25% of cases.

Lateral Condyle Fractures

These types of fracture are the second most common type of elbow fracture in children and account for 15% to 20% of all elbow fractures. This fracture involves the lateral condyle of the distal humerus, which is the outer bony prominence of the elbow. The peak age for the occurrence of lateral condyle fractures is four to ten years old. Most commonly, these are Salter-Harris type IV ( a fracture that transects the metaphysis, physis, and epiphysis) involving the lateral condyle.

Two types of classifications are used to describe lateral condyle fractures:

Milch classification

- Milch 1: Less common type. Fracture line traverses laterally to the trochlear groove. Elbow is stable.

- Milch II: More common type. Fracture passes through the trochlear groove. Elbow is unstable.

Displacement Classification

- Type 1: Displacement less than 2 mm

- Type 2: more than 2 mm but less than 4 mm displacement. Fragment is close to the humerus

- Type 3: Wide displacement, the articular surface is disrupted.

Medial Epicondyle Fractures

These fractures are the third most common type of elbow fracture in children. It is an extra-articular fracture. It involves fracture of the medial epicondyle apophysis, which is located on the posteromedial aspect of the elbow. It commonly occurs in early adolescence, between the ages of nine to 14 years of age. It is more common in boys and occurs during athletic activities such as football, baseball, or gymnastics. The common mechanisms of injury are a posterior elbow dislocation and repeated valgus stress. An example is throwing a baseball repeatedly. One term for this is “little league elbow.”

Common presentation is medial elbow pain, tenderness over the medial epicondyle, and valgus instability.

Radial Head and Neck Fractures

These fractures comprise about 1% to 5% of all pediatric elbow fractures. Most commonly these are Salter-Harris type II fractures that transect the physis and extend into the metaphysis for a short distance. This usually occurs between the ages of nine to ten years.

Olecranon Fractures

Olecranon fractures are uncommon in children. These are mostly associated with radial head and neck fractures.

Etiology

The common mechanism is falling on an outstretched hand, but these can also occur due to a direct blow to the elbow. Elbow injuries most commonly occur in playgrounds, especially while playing on monkey bars.

Epidemiology

Supracondylar fracture is the most common fracture in children under seven years, and these constitute approximately 15% of all pediatric fractures. The peak incidence occurs at around 6 years of age, with a male predominance.

History and Physical

Children commonly present to the emergency room with sharp, intense pain in the elbow and forearm and an inability to extend the arm.

On physical exam, there is obvious deformity of the elbow, swelling around the elbow, and tenderness. Numbness in the forearm or hand is present if there is nerve injury. Pulses should be checked thoroughly to confirm vascular integrity.

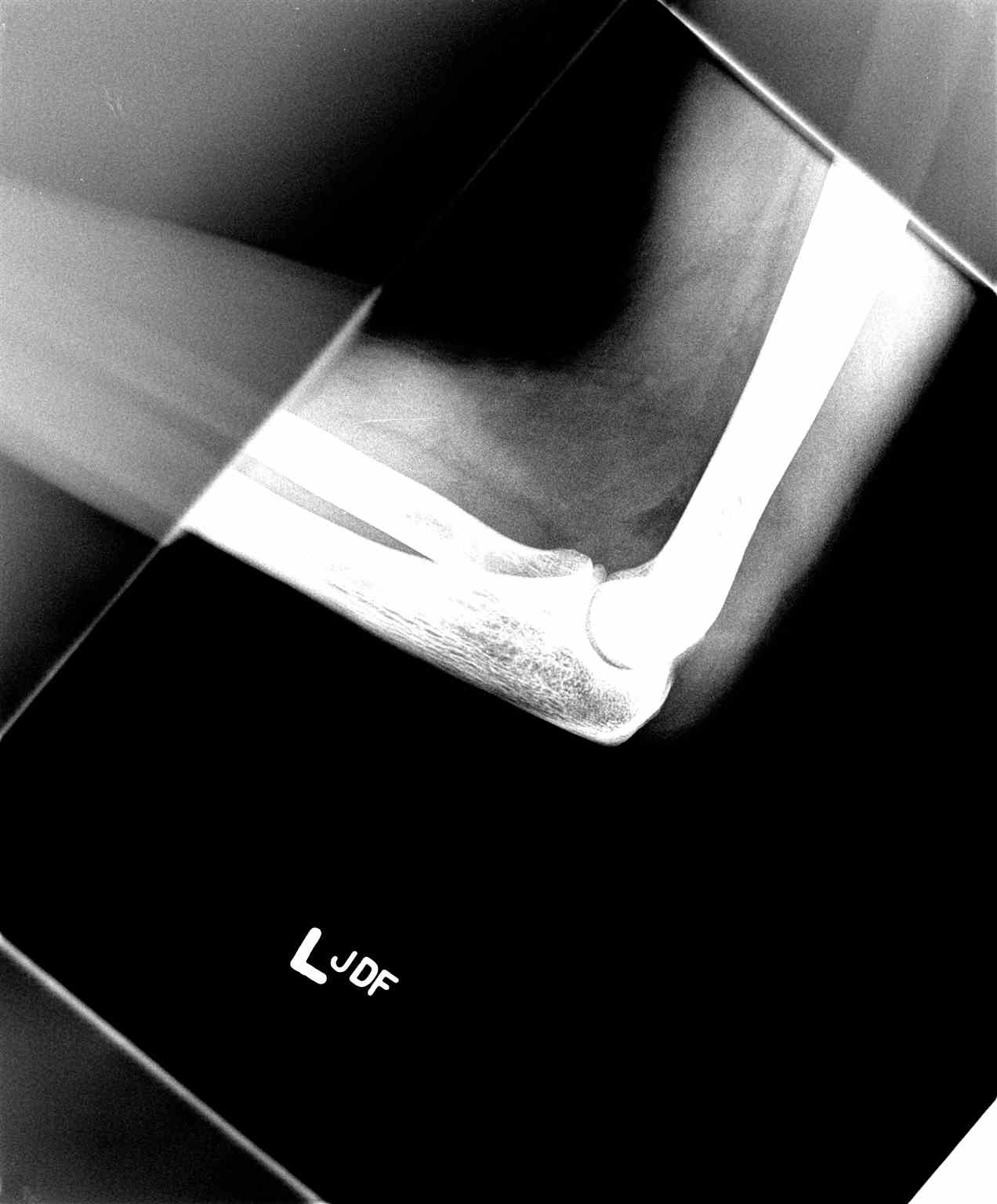

Evaluation

Imaging studies include an x-ray with an anteroposterior and lateral view. An x-ray is the best modality to see the type of fracture and whether bones are displaced or not.

Treatment / Management

Management of all elbow fractures is the same, with few differences.[8][9][10]

Supracondylar Fracture

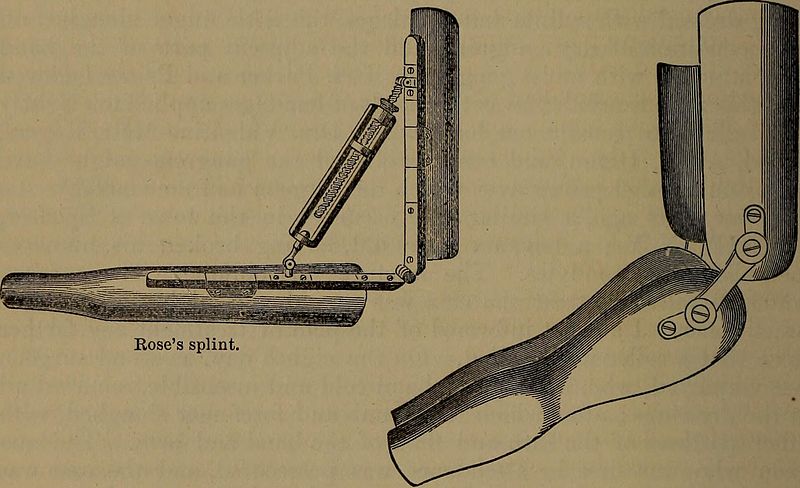

Nondisplaced fractures: Nondisplaced supracondylar fractures do not require operative management. Initial management includes immobilization using a long arm posterior splint while keeping the elbow at 90 degrees of flexion and the forearm in a neutral position.

Initially, it is treated with a splint, which is replaced by a cast as swelling subsides. Follow-up x-ray is necessary after one week to make sure the bone is in place, and the fracture is healing. The cast is usually removed after 3 to 4 weeks.

Displaced Fracture: Displaced fractures require surgical management. The presence of more than 20 degrees of angulation requires orthopedic consultation and reduction under sedation and analgesia.

The following techniques are used:

-

Closed reduction and percutaneous pinning: Displaced bone fragments are repositioned via closed reduction and held by two metal pins placed laterally. Alternatively, three metal pins are utilized if two metal pins are insufficient and there is a severely displaced fracture with free a floating distal segment. It is then covered with a splint or cast to provide stability. Pins are temporary, and both pins and cast are removed after healing has begun in the following few weeks.

-

Open reduction and internal fixation should be performed in the following circumstances:

- Failure of closed reduction

- Vascular insufficiency with a possibility of entrapped brachial artery

- Open fracture

- Consider hospitalization for observation of neurovascular function if there is a displaced fracture or significant soft tissue swelling

Lateral Condyle Fracture

Similar to supracondylar fracture but requires casting for a longer duration (up to six weeks) and close monitoring as there is a tendency for displacement.

Medial Epicondyle Fracture

Treatment of a medial epicondyle fracture is similar to that for supracondylar fracture describe above, with only slightly different technique. Instead of pins, small screws are inserted into the bone to secure the fragments. Therefore, recovery is shorter and requires a splint or cast for a shorter duration (about 1 to 2 weeks).

Radial Head and Neck Fracture

Treatment technique depends on the degree of displacement:

- If less than 30 degrees of displacement of the radial head, immobilization is with a collar without closed reduction.

- If more than 30 degrees of displacement, closed reduction is necessary.

Percutaneous pinning is called for if closed reduction is not successful. A K-wire is inserted to maintain the reduction.

Pearls and Other Issues

Complications

Neuropraxia: This occurs because of nerve injury. It resolves in three to four months. Nerve injury occurs in 11% of supracondylar fractures. Most commonly injured is the interosseous nerve, followed by the radial, median, and ulnar nerves.[11][12]

- The anterior interosseous nerve (arising from the median nerve) and may be involved either due to traction or contusion.

- The radial nerve may be involved with posteromedial displacement

- Median nerve involvement may occur with posterolateral displacement

- Ulnar nerve involvement may occur with a flexion type supracondylar fracture. The ulnar nerve is most commonly involved due to posterior displacement of the proximal fragment.

- Beware that motor testing can only identify anterior interosseous nerve injury. This testing can be done by flexing at the index finger distal interphalangeal and thumb interphalangeal joints and making the "okay" sign. Inability to do so represents a lack of sensory component in the anterior interosseous nerve.

Vascular injury: Brachial artery injury should always be suspected, particularly if the radial pulse is absent. However, the vascular injury may occur even if the hand is pink and well perfused. This may be due to partial transection of a vessel.

Compartment syndrome: this may occur after a supracondylar fracture. Evaluate for the early or impending signs by determining if a radial pulse is absent. This injury results from prolonged ischemia of the forearm. It should be suspected if the following are present:

- Inability to open the hand in children

- Pain on passive extension of the fingers

- Tenderness over the forearm

- Absence of a radial pulse

- A careful neurovascular examination is therefore important to promptly recognize this serious complication.

Malunion: Fracture malunion can lead to cubitus valgus or cubitus varus deformity (common in supracondylar fracture). A common complication is a loss of the carrying angle, which results in a cubitus varus, or “Gunstock,” deformity.

Nonunion: Lateral condylar fractures are more prone to nonunion. These, therefore, require revision surgery.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of elbow fractures is with an interprofessional team that includes the emergency department physician, orthopedic surgeon, nurse practitioner, radiologist and physical therapist. It is important to be aware that elbow fractures can be associated with neurovascular compromises. Undisplaced fractures are managed conservatively but all displaced fractures need surgery. Most of the patients need extensive rehabilitation to regain motion and strength. A few patients will have limited range of motion and pain even after full recovery.[13]