Introduction

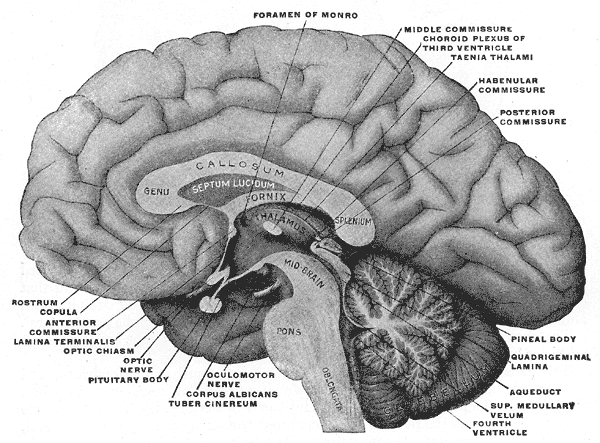

The human brain is perhaps the most complex of all biological systems, with the mature brain composed of more than 100 billion information-processing cells called neurons.[1] The brain is an organ composed of nervous tissue that commands task-evoked responses, movement, senses, emotions, language, communication, thinking, and memory. The three main parts of the human brain are the cerebrum, cerebellum, and brainstem.

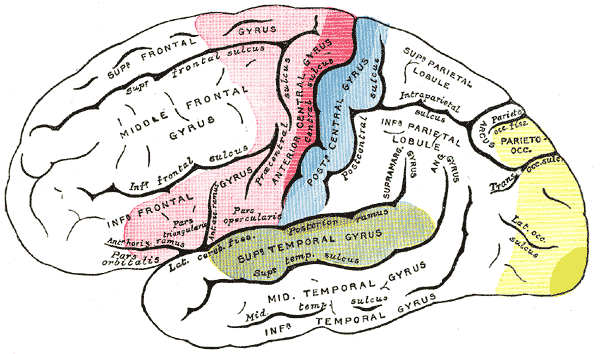

The cerebrum is divided into the right and left hemispheres and is the largest part of the brain. It contains folds and convolutions on its surface, with the ridges found between the convolutions called gyri and the valleys between the gyri called sulci (plural of sulcus). If the sulci are deep, they are called fissures. Both cerebral hemispheres have an outer layer of gray matter called the cerebral cortex and inner subcortical white matter.

Located in the posterior cranial fossa, above the foramen magnum, the cerebellum's primary function is to modulate motor coordination, posture, and balance. It is comprised of the cerebellar cortex and deep cerebellar nuclei, with the cerebellar cortex being made up of three layers; the molecular, Purkinje, and granular layers. The cerebellum connects to the brainstem via cerebellar peduncles.

The brainstem contains the midbrain, pons, and medulla. It is located anterior to the cerebellum, between the base of the cerebrum and the spinal cord.

Issues of Concern

Studies of brain function have focused on analyzing the variations of the electrical activity produced by the application of sensory stimuli. However, it is also essential to study additional features and functions of the brain, including information processing and responding to environmental demands.[2]

The brain works precisely, making connections, and is a deeply divided structure that has remained not entirely explained or examined.[3] Although researchers have made significant progress in experimental techniques, the human cognitive function that emerges from neuronal structure and dynamics is not entirely understood.[4]

Cellular Level

At the beginning of the forebrain formation, the neuroepithelial cells undergo divisions at the inner surface of the neural tube to generate new progenitors. These dividing neuroepithelial cells transform and diversify, leading to radial glial cells (RGCs).

RGCs also work as progenitors with the capacity to regenerate themselves and produce other types of progenitors, neurons, and glial cells.[5] RGCs have long processes that connect with the neuroepithelium and function as a guide for the migration of neuron cells to ensure that neurons find their resting place, mature, and send out axons and dendrites to participate directly in synapses and electrical signaling. Neurons get produced along with glial cells; glial cells bring support and create an enclosed environment in which neurons can perform their functions.

Glial cells (astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, microglial cells) have well-known roles, which include: keeping the ionic medium of neurons, controlling the rate of nerve signal propagation and synaptic action by regulating the uptake of neurotransmitters, providing a platform for some aspects of neural development, and aiding in recovery from neural damage.

Gray matter is the main component of the central nervous system (CNS) and consists of neuronal cell bodies, dendrites, myelinated and unmyelinated axons, glial cells, synapses, and capillaries. The cerebral cortex is made up of layers of neurons that constitute the gray matter of the brain. The subcortical (beneath the cortex) area is primarily white matter composed of myelinated axons with fewer quantities of cell bodies when compared to gray matter.

Although neurons can have different morphologies, they all contain four common regions: the cell body, the dendrites, the axon, and the axon terminals, each with its respective functions.

The cell body contains a nucleus where proteins and membranes are synthesized. These proteins travel through microtubules down to the axons and terminals via a mechanism known as anterograde transport. In retrograde transport, damaged membranes and organelles travel from the axon toward the cell body along axonal microtubules. Lysosomes are only present in the cell body and are responsible for containing and degrading damaged material. The axon is a thin continuation of a neuron that allows electrical impulses to be sent from neuron to neuron.

Astrocytes occupy 25% of the total brain volume and are the most abundant glial cells.[6] They are classified into two main groups: protoplasmic and fibrous. Protoplasmic astrocytes appear in gray matter and have several branches that contact both synapses and blood vessels. Fibrous astrocytes are present in the white matter and have long fiber-like processes that contact the nodes of Ranvier and the blood vessels. Astrocytes use their connections to vessels to titrate blood flow in synaptic activity responses. Astrocytic endfeet, which forms tight junctions between endothelial cells and the basal lamina, gives rise to the formation of the blood-brain barrier (BBB).[7]

The primary function of oligodendrocytes is to make myelin, a proteolipid critical in maintaining electrical impulse conduction and maximizing velocity. Myelin is located in segments separated by nodes of Ranvier, and their function is equivalent to those of Schwan cells in the peripheral nervous system.

The macrophage populations of the CNS include microglia, perivascular macrophages, meningeal macrophages, macrophages of the circumventricular organs (CVO), and the microglia of the choroid plexus. Microglia are phagocytic cells representing the immune and support system of the CNS and are the most abundant cells of the choroid plexus.[8]

Development

Human brain development starts with the neurulation process from the ectodermic layer of the embryo and takes, on average, 20 to 25 years to mature.[9] It occurs in a sequential and organized manner beginning with the neural tube formation at the third or fourth week of gestation. This is followed by cell migration and proliferation that leads to the folding of the cerebral cortex to increase its size and surface area, creating a more complex structure. Failure of this migration and proliferation leads to a smooth brain without sulci or gyri, termed lissencephaly.[10] At birth, the general architecture of the brain is mostly complete, and by the age of 5 years, the total brain volume is about 95% of its adult size. Generally, the white matter increases with age, while the gray matter decreases with age.

The most prominent white matter structure of the brain, the corpus callosum, increases by approximately 1.8% per year between the ages of 3 and 18 years.[11] The corpus callosum conjugates the activity of the right and left hemispheres and allows for the progress of higher-order cognitive abilities.

Gray matter in the frontal lobe undergoes continued structural development reaching its maximal volume at 11 to 12 years of age before slowing down during adolescence and early adulthood. The gray matter in the temporal lobe follows a similar development pattern, reaching its maximum size at 16 to 17 years of age with a slight decline afterward.[12]

Below is a list of the brain vesicles and the areas of the brain which develop from them.[13]

Prosencephalon (Forebrain)

- Telencephalon

- Cerebral cortex

- Basal ganglia (caudate nucleus, putamen, and globus pallidus)

- Hippocampus

- Lateral ventricles

- Diencephalon

- Thalamus

- Hypothalamus

- Epithalamus (pineal gland)

- Subthalamus

- Posterior pituitary

- Retina

- Optic nerve

- Third ventricle

Mesencephalon (midbrain)

- Mesencephalon

- Midbrain

- Cerebral aqueduct

Rhombencephalon (hindbrain)

- Metencephalon

- Pons

- Cerebellum

- Fourth ventricle (rostral)

- Myelencephalon

- Medulla

- Fourth ventricle (caudal)

Organ Systems Involved

The brain and the spinal cord comprise the central nervous system (CNS). The peripheral nervous system (PNS) subdivides into the somatic nervous system (SNS) and the autonomic nervous system (ANS). The SNS consists of peripheral nerve fibers that collect sensory information to the CNS and motor fibers that send information from the CNS to skeletal muscle. The ANS functions to control the smooth muscle of the viscera and glands and consists of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), the parasympathetic nervous system (PaNS), and the enteric nervous system (ENS).

Nerves from the brain connect with multiple parts of the head and body, leading to various voluntary and involuntary functions. The ANS drives basic functions that control unconscious activities such as breathing, digestion, sweating, and trembling.

The ENS provides the intrinsic innervation of the gastrointestinal system and is the most neurochemically diverse branch of the PNS.[14] Neurotransmitters such as norepinephrine, epinephrine, dopamine, and serotonin have recently been a topic of interest due to their roles in gut physiology and CNS pathophysiology, as they aid in regulating gut blood flow, motility, and absorption.[15]

Function

Cerebrum

The cerebrum controls motor and sensory information, conscious and unconscious behaviors, feelings, intelligence, and memory. The left hemisphere controls speech and abstract thinking (the ability to think about things that are not present). In contrast, the right hemisphere controls spatial thinking (thinking that finds meaning in the shape, size, orientation, location, and phenomena).

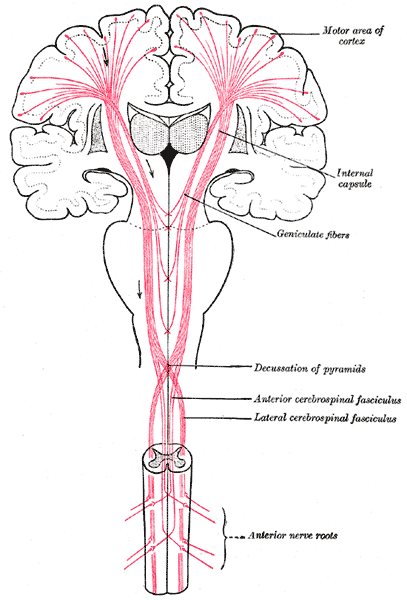

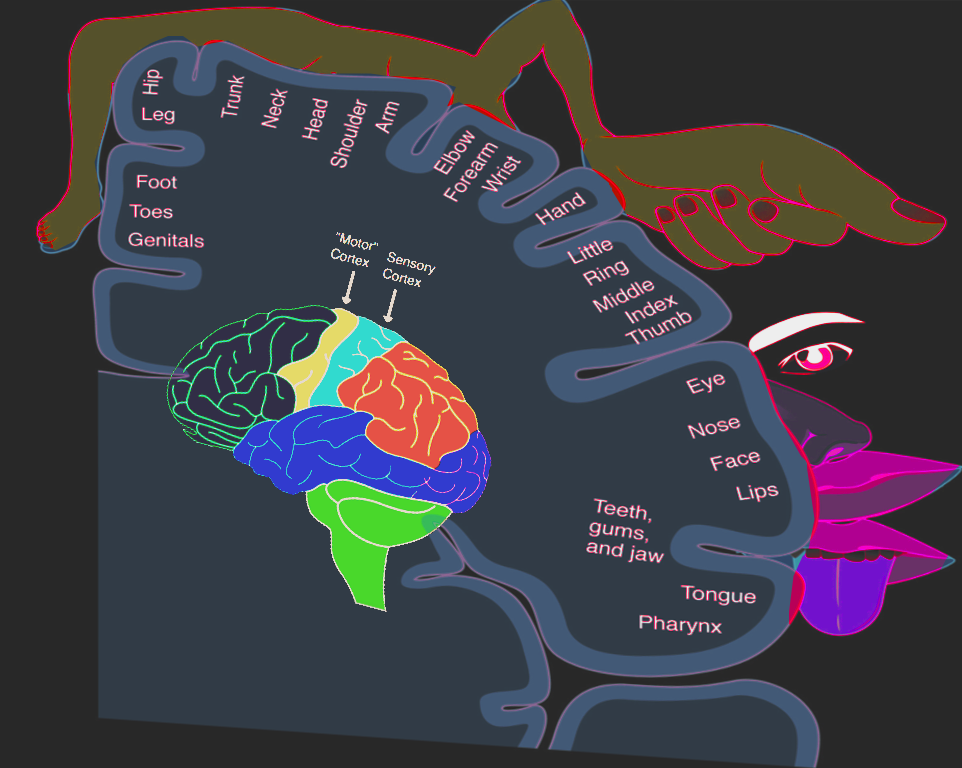

The motor and sensory neurons descending from the brain cross to the opposite side in the brainstem. This crossing means that the right side of the brain controls the motor and sensory functions of the left side of the body, and the left side of the brain controls the motor and sensory functions of the right side of the body. Hence, a stroke affecting the left brain hemisphere, for example, will exhibit motor and sensory deficits on the right side of the body.

Sensory neurons bring sensory input from the body to the thalamus, which then relays this sensory information to the cerebrum. For example, hunger, thirst, and sleep are under the control of the hypothalamus.

The cerebrum is composed of four lobes:

- Frontal lobe: Responsible for motor function, language, and cognitive processes, such as executive function, attention, memory, affect, mood, personality, self-awareness, and social and moral reasoning.[16] The Broca area is located in the left frontal lobe and is responsible for the production and articulation of speech.

- Parietal lobe: Responsible for interpreting vision, hearing, motor, sensory, and memory functions.

- Temporal lobe: In the left temporal lobe, the Wernicke area is responsible for understanding spoken and written language. The temporal lobe is also an essential part of the social brain, as it processes sensory information to retain memories, language, and emotions.[17] The temporal lobe also plays a significant role in hearing and spatial and visual perception.

- Occipital lobe: The visual cortex is located in the occipital lobe and is responsible for interpreting visual information.

Cerebellum

The cerebellum controls the coordination of voluntary movement and receives sensory information from the brain and spinal cord to fine-tune the precision and accuracy of motor activity. The cerebellum also aids in various cognitive functions such as attention, language, pleasure response, and fear memory.[18]

Brainstem

The brainstem acts as a bridge that connects the cerebrum and cerebellum to the spinal cord. The brainstem houses the principal centers which perform autonomic functions such as breathing, temperature regulation, respiration, heart rate, wake-sleep cycles, coughing, sneezing, digestion, vomiting, and swallowing. The brainstem contains both white and gray matter. The white matter consists of fiber tracts (neuronal cell axons) traveling down from the cerebral cortex for voluntary motor function and up from the spinal cord and peripheral nerves, allowing somatosensory information to travel to the highest parts of the brain.[19]

Mechanism

The brain represents 2% of the human body weight and consumes 15% of the cardiac output and 20% of total body oxygen. The resting brain consumes 20% of the body's energy supply. When the brain performs a task, the energy consumption increases by an additional 5%, proving that most of the brain's energy consumption gets used for intrinsic functions.

The brain uses glucose as its principal source of energy. During low glucose states, the brain utilizes ketone bodies as its primary energy source. During exercise, the brain can use lactate as a source of energy.

In the developing brain, neurons follow molecular signals from regulatory cells like astrocytes to determine their location, the type of neurotransmitter they will secrete, and with which neurons they will communicate, leading to the formation of a circuit between neurons that will be in place during adulthood. In the adult brain, developed neurons fit in their corresponding place and develop axons and dendrites to connect with the neighboring neurons.[20]

Neurons communicate via neurotransmitters released into the synaptic space, a 20 to 50-nanometer area between neurons. The neuron that releases the neurotransmitter into the synaptic space is called the presynaptic neuron, and the neuron that receives the neurotransmitter is called the postsynaptic neuron. An action potential in the presynaptic neuron leads to calcium influx and the subsequent release of neurotransmitters from their storage vesicle into the synaptic space. The neurotransmitter then travels to the postsynaptic neuron and binds to receptors to influence its activity. Neurotransmitters are rapidly removed from the synaptic space by enzymes.[21]

The oligodendrocytes in the CNS produce myelin. Myelin forms insulating sheaths around axons to allow the swift travel of electrical impulses through the axons. The nodes of Ranvier are gaps in the myelin sheath of axons, allowing sodium influx into the axon to help maintain the speed of the electrical impulse traveling through the axon. This transmission is called saltatory nerve conduction, the "jumping" of electrical impulses from one node to another. It ensures that electrical signals do not lose their velocity and can propagate long distances without signal deterioration.[22]

Related Testing

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) can track the effects of neural activity and the energy that the brain consumes by measuring components of the metabolic chain. Other techniques, such as single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), study cerebral blood flow and neuroreceptors. Positron emission tomography (PET) assesses the glucose metabolism of the brain.[23] Electroencephalography (EEG) records the brain's electrical activity and is very useful for detecting various brain disorders. Advancements in these techniques have enabled a broader vision and objective perceptions of mental disorders, leading to improved diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis.

Pathophysiology

Injury to the brain stimulates the proliferation of astrocytes, an immunological response to neurodegenerative disorders called "reactive gliosis."[24] Damage to neural tissue promotes molecular and morphological changes and is essential in the upregulation of the glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP). On the other hand, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) allows the transition from non-reactive to reactive astrocytes, and its inhibition improves axonal regeneration and rapid recovery. This means that when astrocytes are reactive, they proliferate and hypertrophy, leading to glial scar formation.

The microglia represent the immune and support system of the CNS. They are neuroprotective in the young brain but can react abnormally to stimuli in the aged brain and become neurotoxic and destructive, leading to neurodegeneration.[25] As the brain ages, microglia acquire an increasingly inflammatory and cytotoxic phenotype, generating a hazardous environment for neurons.[26] Hence, aging is the most critical risk factor for developing neurodegenerative diseases.

The brain is surrounded by cerebrospinal fluid and is isolated from the bloodstream by the blood-brain barrier (BBB). In cases like infectious meningitis and meningoencephalitis, acute inflammation causes a breakdown of the BBB, leading to the influx of blood-borne immune cells into the CNS. In other inflammatory brain disorders such as Alzheimer disease (AD), Parkinson disease (PD), Huntington disease (HD), or X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy, the primary insult is due to degenerative or metabolic processes, and there is no breakdown of the BBB.[27]

Oligodendrocyte loss can occur due to the production of reactive oxygen species or the activation of inflammatory cytokines, causing decreased myelin production and leading to conditions such as multiple sclerosis (MS).[22]

Disturbances in the neurotransmitter systems are related to these substances' production, release, reuptake, or receptor impairments and can cause neurologic or psychiatric disorders. Glutamate is the brain's most abundant excitatory neurotransmitter, while GABA is the primary inhibitory transmitter. Glycine has a similar inhibitory action in the posterior parts of the brain. Acetylcholine aids in processes such as muscle stimulation at the neuromuscular junction (NMJ), digestion, arousal, salivation, and level of attention. Dopamine is involved in the reward and motivational component, motor control, and the regulation of prolactin release. Serotonin influences mood, feelings of happiness, and anxiety. Norepinephrine is involved in arousal, alertness, vigilance, and attention.

Cerebral oxygen delivery and consumption rates are ten times higher than global body values.[28] Blood glucose represents the primary energy source for the brain, and the BBB is highly permeable to it. During low glucose states, the body has developed multiple ways to keep blood glucose within the normal range. As the level drops below 80 mg/dL, pancreatic beta-cells decrease insulin secretion to avoid further glucose decrease. If glucose drops further, pancreatic alpha-cells secrete glucagon, and the adrenal medulla releases epinephrine. Glucagon and epinephrine increase blood glucose levels. Cortisol and growth hormone also act to increase glucose, but they depend on the presence of glucagon and epinephrine to work.

Clinical Significance

Damage to the Cerebrum

- Frontal lobe - Damage to the frontal lobe causes interruption of the higher functioning brain processes, including social behavior, planning, motivation, and speech production. Individuals with frontal lobe damage may be unable to regulate their emotions, have meaningful or appropriate social interactions, maintain their past personality traits, or make difficult decisions.[29]

- Temporal lobe - The Wernicke area is located in the superior temporal gyrus in an individual's dominant hemisphere, which is the left hemisphere for 95% of people. Damage to the left (dominant) temporal lobe can lead to Wernicke aphasia. This is typically referred to as "word salad" speech, where the patient will speak fluently, but their words and sentences will lack meaning.[30] Damage to the right (non-dominant) temporal lobe may lead to persistent talking and deficits in nonverbal memory, processing certain aspects of sound or music (tone, rhythm, pitch), and facial recognition (prosopagnosia).

- Parietal lobe - Damage to the frontal aspect of the parietal lobe may lead to impaired sensation and numbness on the contralateral side of the body. An individual may have difficulty recognizing texture and shape and may be unable to identify a sensation and its location on their body. Damage to the middle aspect of the parietal lobe can lead to right-left disorientation and difficulty with proprioception. Damage to the non-dominant (right) parietal lobe may lead to apraxia (difficulty with performing purposeful motions such as combing hair or brushing teeth) and difficulty with spatial orientation and navigation (they may get lost in a once familiar area). Patients with non-dominant parietal lobe damage, usually from a middle cerebral artery stroke, may neglect the side opposite of the brain damage (usually the left side), which may manifest as only shaving the right side of their face or drawing a clock with all of the numbers on the right side of the circle.[31]

- Occipital lobe - Damage to the occipital lobe may lead to visual defects, color agnosia (inability to identify colors), movement agnosia (difficulty recognizing object movements), hallucinations, illusions, and the inability to recognize written words (word blindness).

Damage to the Cerebellum

Damage to the cerebellum can lead to ataxia, dysmetria, dysarthria, scanning speech, dysdiadochokinesis, tremor, nystagmus, and hypotonia. To test for possible cerebellar dysfunction, a bedside neurologic exam is commonly the first step. This exam may include the Romberg test, heel-to-shin test, finger-to-nose test, and rapid alternating movement test.[32]

Damage to the Brainstem

Damage to the brainstem may present as muscle weakness, visual changes, dysphagia, vertigo, speech impairment, pupil abnormalities, insomnia, respiratory depression, or death.

Neurodegenerative Diseases

Neuronal degeneration worsens with age and can affect different areas of the brain leading to movement, memory, and cognition problems.

Parkinson disease (PD) occurs due to the degeneration of the neurons that synthesize dopamine, leading to motor function deficits. Alzheimer disease (AD) occurs due to abnormally folded protein deposition in the brain leading to neuronal degeneration. Huntington disease occurs due to a genetic mutation that increases the production of the neurotransmitter glutamate. Excessive amounts of glutamate lead to the death of neurons in the basal ganglia producing movement, cognitive, and psychiatric deficits. Vascular dementia occurs due to the death of neurons resulting from the interruption of blood supply.

Although neurodegenerative diseases are not classically caused by disturbed metabolism, research has shown that there is a reduction in glucose metabolism in Alzheimer disease.[33]

Demyelinating Diseases

Demyelinating diseases result from damage to the myelin sheath that covers the nerve cells in the white matter of the brain, spinal cord, and optic nerves. For example, multiple sclerosis and leukodystrophies are a consequence of oligodendrocyte damage.

Stroke

A stroke is caused by an interruption in the blood supply to the brain, which may ultimately lead to neuronal death. This condition can result in one of several neurological problems depending on the affected region.

Brain Death

Neurologic evaluation of brain death is a complicated process that non-specialists and families might misunderstand.[34] Brain death is the complete and irreversible loss of brain activity, including the brainstem. It requires verification through well-established clinical protocols and the support of specialized tests.

Hypoglycemia

Glucose is the primary energy source responsible for maintaining brain metabolism and function. The most significant amount of glucose is used for information processing by neurons.[35] The brain requires a continuous supply of glucose as it has limited glucose reserves. CNS symptoms and signs of hypoglycemia include focal neurological deficits, confusion, stupor, seizure, cognitive impairment, or death.