Introduction

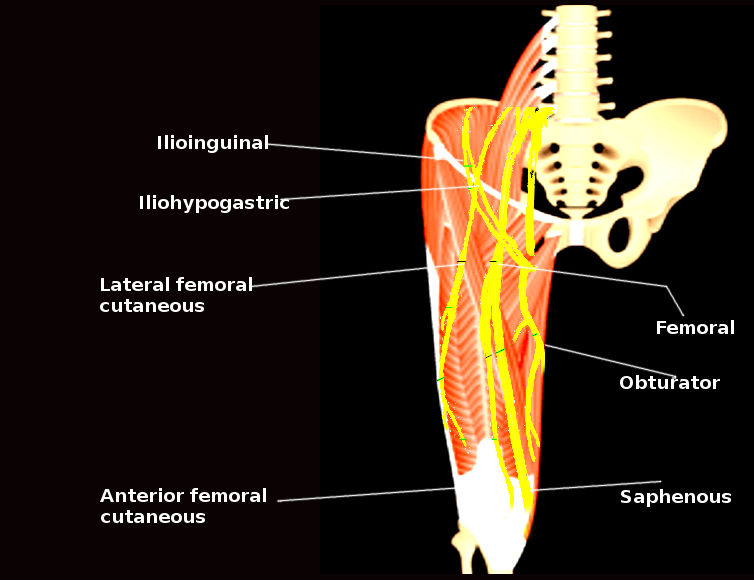

The three major nerves of the thigh originate from the lumbar and sacral plexuses, providing both motor and sensory branches to structures throughout the pelvis and the lower limbs. While slight anatomical variations can exist, the location and function of each of the three nerves have been consistently anatomically preserved. Therefore, when signs and symptoms arise in patients, the clinicians can quickly localize lesions that affect these nerves.[1][2]

Structure and Function

The function of the three major nerves and their branches in the thigh is to provide both somatosensory information to the cortex and to innervate the muscles of the thigh. The thigh can be broken down into three different compartments: anterior, posterior, and medial. The anterior compartment has the main action of allowing extension of the thigh at the knee joint via the femoral nerve. The posterior compartment contains muscles that allow the flexion of the leg at the knee joint and to also allow extension of the thigh at the hip joint via the sciatic nerve. The medial compartment of the leg is innervated by the obturator nerve and serves to allow adduction at the hip joint.

Embryology

The lumbar and sacral plexuses both contribute fibers towards the three major nerves that serve to innervate the thigh. The lumbar plexus is formed by the anterior rami of nerve roots L1 through L4 while also receiving contributions from T12. The sacral plexus is formed by the anterior rami of the sacral spinal nerves S1 through S4, while also receiving branches from spinal nerves L4 and L5. It is from the lumbar plexus that the obturator nerve and the femoral nerve arise. The specific spinal nerve roots of the obturator nerve and the femoral nerve are the same, L2 through L4. The sciatic nerve, however, is a major division of the sacral plexus taking in inputs from L4 through S3.

How these nerves make their way to the target cells of the muscles of the thigh is yet to be determined. Some theories about how these nerves advance from the spinal cord to their target muscles have been put forth, but none have been confirmed. It has been described that nerve trunks advance with a filopodium of the pioneer growth cone in order to allow guidance of the nerves to their assigned tissues. Other studies have also shown that manipulating the position of the target muscle does not interfere with the nerve’s ability to progress toward it for innervation. It has been discussed that ventral axonal attraction may be mediated by binding of netrins, a chemoattractant, to an axonal receptor but this is still being investigated.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

While the nerves receive their blood supply through various tributaries throughout their course through the body, the vessels that course near the major nerves are the femoral vessels and the common iliac vessels. The femoral nerve goes into the femoral triangle and passes lateral to both the femoral artery and vein. The obturator nerve passes posteriorly to the common iliac artery and vein while the nerve travels toward to obturator foramen.

Nerves

The femoral nerve, which supplies the muscles of the anterior compartment, travels inferiorly from the lumbar plexus and passes through the psoas major. It is after it passes through the psoas major that the nerve goes in through the pelvis where it travels posteriorly to the inguinal ligament into the thigh. It is after passing the inguinal ligament that the femoral nerve divides into its anterior and posterior divisions.[3]

The posterior compartment of the thigh is innervated by divisions of the large sciatic nerve. The sciatic nerve comes from the sacral plexus and introduces itself through the greater sciatic foramen. As it passes through the greater sciatic foramen, it emerges with the piriformis muscle being anterior to its exit point and then descends inferiorly. The nerve moves through the gluteal area and begins to enter the posterior compartment of the thigh by traveling posterior to the long head of the biceps femoris. Recent literature has described the sciatic nerve as two individual nerves, the tibial nerve and the common fibular nerve, that have been bundled together in a common connective tissue sheath. While authors agree that the sciatic nerve separates into the two individual nerves at the apex of the popliteal fossa, it has been discussed that approximately 12% of people have separation of the sciatic nerve as it leaves the pelvis.[4][5]

The obturator nerve gets its major contributions from the lumbar plexus. The obturator nerve travels inferiorly through the psoas major and exits on the medial border of the muscle. It then moves laterally along the pelvis towards to obturator foramen and then crosses into the obturator canal. The obturator nerve then splits into its anterior and posterior divisions and innervates surrounding structures in the medial compartment of the thigh.[6]

Muscles

The anterior compartment is innervated by the femoral nerve which has two major branches, the anterior and the posterior. The anterior branch of the femoral nerve gives off anterior cutaneous branches to provide somatosensory information via the intermediate femoral cutaneous nerve and the medial femoral cutaneous nerve. This anterior branch also gives muscular branches to the pectineus muscle. The posterior branch of the femoral nerve includes innervation to the rectus femoris, the vastus lateralis, the vastus medialis, and the vastus intermedius. It is through these muscles that the anterior compartment muscles can cause extension of the thigh at the knee joint. The innervation of the sartorius is directly off the femoral nerve itself.

The posterior compartment of the thigh has the primary function of extending the thigh at the hip joint and also flexing the leg at the knee joint. The major nerve that supplies this compartment is the sciatic nerve. The muscles that make up the posterior compartment of the leg include the biceps femoris, the semitendinosus, and the semimembranosus. The biceps femoris can be further described as having a short head and a long head. The innervation for these muscles is all via the sciatic nerve. However, more specifics are warranted. All the muscles with the exception of the short head of the biceps femoris receive specific innervation via the tibial nerve, which is a division of the sciatic nerve. The short head of the biceps femoris receives innervation via the sciatic nerves other portion, the common fibular nerve.

The medial compartment of the thigh’s main action is to innervate muscles that provide adduction for the hip joint. The obturator nerve has three major branches: the cutaneous branch, the anterior branch, and the posterior branch. The cutaneous branch provides somatosensory information of the skin from the medial aspect of the thigh. The anterior branch distributes fibers to the adductor longus, adductor brevis, and to the gracilis muscle. The posterior branch provides fibers to the adductor magnus and the adductor brevis.

Surgical Considerations

Nerve blocks are commonly used in this region to promote pain management for chronic pain or limb surgery. This is especially useful in situations where patients cannot tolerate a general anesthetic. Nerve blocks are frequently carried out under ultrasound guidance, but anatomical landmarks have been proven useful in confirming correct anesthetic placement. One such block is the obturator nerve block, where the anesthetic is injected inferiorly to the pubic tubercle and lateral to the adductor longus muscle. Another is the femoral nerve block. While performing a femoral nerve block, it is imperative that clinicians are aware of surrounding structures during their procedure. From lateral to medial, the structures are the femoral nerve, then artery, and subsequently the vein. This is commonly remembered by the pneumonic NAVY, with the Y signifying the midline of the patient. This knowledge is also essential if arterial or venous sampling is required from a femoral vessel.

The literature has shown that the sciatic nerve has been at risk during a total hip arthroplasty. The total injury risk is between 0.5% and 2.0%, with an increased risk during revision procedures of 1.7% to 7.6%.

Compartment syndrome of the thigh is an important consideration following trauma to the lower limb. Compartment syndrome occurs when the pressure inside of any compartment increases to the point where it reduces the ability of arteries to supply the muscles and nerves within that compartment Compartment syndrome of the thigh can affect the any of the three major nerves to the thigh. Following the clinical symptoms, pain out of proportion, sensory deficits, and clinical signs of swelling can all point to the compartment or compartments affected. Treatment is immediate fasciotomy.[7][8][9]

Clinical Significance

The nerves of the thigh can be inadvertently injured through other mechanisms as well. An example of this is the intramuscular injection in the gluteal region. The gluteal region is divided into four quadrants by two imaginary lines to minimize the risk of sciatic nerve injury during this procedure. One travels inferiorly from the highest point of the iliac crest while the other travels transversely halfway between the previous iliac crest point and the ischial tuberosity. The sciatic nerve travels through the lower medial quadrant, so intramuscular injections are recommended to be placed in the upper lateral quadrant of the gluteal region.

Sciatica is a medical condition that results from compression of the sciatic nerve. Common signs of sciatica include weakness in the knee, difficulty in rotating the ankle, and decreased reflex speed. Symptoms include numbness, paraesthesia, and pain or weakness in the areas innervated by the sciatic nerve. Causes of sciatica include any mechanism that could potentially cause compression of the sciatic nerve such as pregnancy, slipped disks, lumbar spine stenosis, or acute injury. Piriformis syndrome, most commonly seen in people who are seated for long periods at a time, results from the piriformis muscle compressing the sciatic nerve as it travels toward the posterior compartment of the thigh.