Introduction

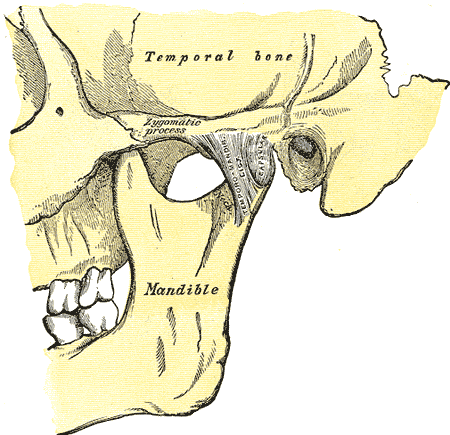

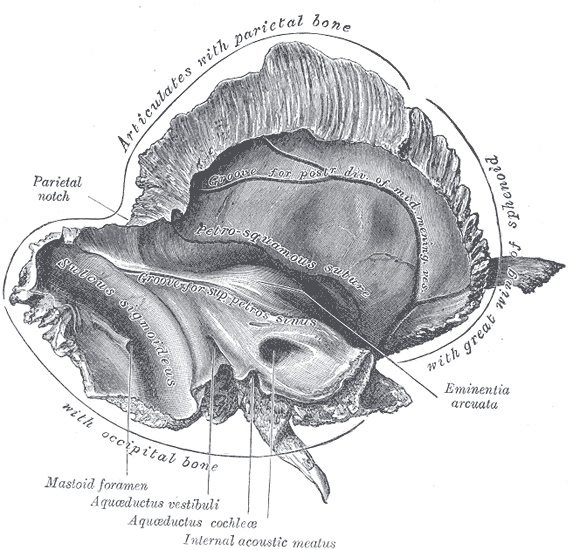

The major structure of the temporal region is the temporal bone. The term "temporal" region of the skull and the "temporal" bone specifically comes from the Latin word tempus or time. Grey hairs first appear in the temporal area in males, thus a mark of age or time. Another term for the temporal bone is the petrous pyramid, from the Latin petrosal or hard. The compact portion of a temporal bone specimen is very hard. The temporal bone resembles a pyramid that has fallen over, pointing with its apex at the sphenoid sinus (the pyramids in Giza Egypt are four-sided, while the temporal bone pyramid is three-sided). The anterior portion of the petrous pyramid forms the posterior aspect of the middle cranial fossa. The caudal or inferior portion contains the exiting jugular vein and the entering carotid artery. Finally, the posterior portion forms a lateral portion of the posterior cranial fossa and contains the channel or internal auditory canal for the seventh and eighth cranial nerves.[1][2][3]

Structure and Function

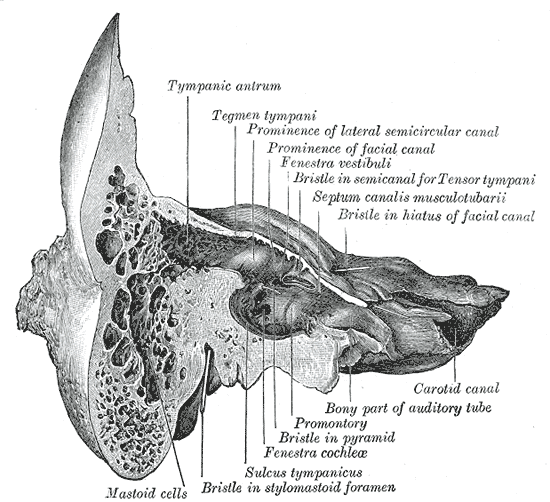

The main functions of the temporal bone are hearing and balance. Sound enters through the external auditory canal and strikes and vibrates the drum or the tympanum. The latter connects to the ossicles (Latin for little bones), the first being the malleus (Latin for hammer), which appears to strike and does connect to the body of the incus (Latin for an anvil). The incus, in turn, connects to an ossicle that looks like a stirrup of a horse saddle, thus originating in name from stirrup (Italian), or stare (Latin for the stand) and pes (Latin for foot), hence the word stapes. The stapes conducts sound through the oval window into the vestibule (from the Latin word vestibulum or entrance hall), and eventually into the cochlea (Latin for snail shell), where the hearing cells live. These cells send signals to the brain stem via the cochlear division of cranial nerve eight. Balance is managed by the hair cells in the three semicircular canals of the vestibular apparatus, and signals go to the brain via the vestibular division of cranial nerve VIII. The muscle control of the malleus, used to dampen sound, is a division of cranial nerve V3 (this nerve, besides receiving mandible sensation also controls the muscles of mastication, among other structures). The stapedial tendon also dampens sound and is a branch of cranial nerve VII.[4][5]

Embryology

Embryologically, the temporal bone divides into two basic anatomic regions. The cranial nerves and the otic capsule (the cochlea and vestibular apparatus) arise from neuro-ectoderm. Everything else, including the ossicles, arises from ectoderm. Thus, in a case of hemifacial dysplasia (ectoderm), the cause for hearing loss, if the external canal is still patent, it is often from ossicular dysfunction. Hearing loss on a congenital basis can also be due to neuro-ectoderm dysplasia, such as no otic capsule (Michele’s anomaly) or otic capsule dysplasia where the cochlea and vestibular are malformed into blobs or a common cavity anomaly.

The distinction is important between the two basic embryological types since an anomaly of the ossicles can be bypassed, usually, with a BAHA device (bone-anchored hearing aid) that is placed under the skin into the mastoid portion of the temporal bone. A hearing aid-like device picks up sound waves and delivers digital pulses to the inner ear via the implant. With otic capsule dysplasia, the hair cells become compromised. Thus, a BAHA device or even a cochlear implant will not work to restore hearing. For this neuroectoderm group of otic capsule dysplasia, a brainstem implant into a lateral recess of the fourth ventricle of the brain is an option. This implant connects to a hearing aid that transmits sound to the brainstem device and finally to the cochlear nuclei of the brain stem.

It is important to remember that the outflow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from the ventricular system of the brain is mostly through the midline outlet of the fourth ventricle (80%), with only 10% exiting through the lateral recesses. Thus, no compromise of CSF flow occurs with a brain stem implant.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The superficial temporal artery (STA) is the major branch of the temporal artery, which originates from the external carotid artery, arising above the takeoff of the internal maxillary artery. The STA then runs through the posterior portion of the parotid gland, beneath the facial nerve, and then crosses the posterior aspect of the zygomatic arch before branching into frontal and parietal branches, running within the temporalis muscle of the skull. The STA may dilate for unknown reasons and cause migraine headaches, which can be lessened with botox injections. The STA may also be involved with giant cell arteritis, an idiopathic inflammation of the artery, which necessitates a manually guided biopsy of the STA for diagnosis. This latter pathology can respond to oral steroid administration.

In the past, the STA has been used to bypass middle cerebral occlusion or stenotic diseases by anastomosing the STA to the middle cerebral artery through a burr hole in the skull. This technique is only rarely used today for vascular disease. However, the STA can serve as a bypass vascular graft for specific head and neck tumors where other arteries to facial structures need to be sacrificed. The arterial supply to the temporal bone is also partly from the ascending pharyngeal artery of the external carotid artery. The AICA or anterior inferior cerebellar artery is a significant supplier of the internal auditory canal and cranial nerves VII and VIII. The venous drainage is from inferior and superior petrosal veins into the jugular fossa of the skull base, and then into the internal jugular vein.

Nerves

If one looks at the internal auditory canal as if one is standing in the posterior cranial fossa, the anterior superior cranial nerve is cranial nerve seven or the facial nerve (a phrase to help remember, "seven-up"). The inferior anterior nerve is the cochlear division of cranial nerve (a phrase to help remember, "coke down"). The superior and inferior vestibular nerves for balance are posterior to the internal auditory canal. Running with and part of the seventh cranial nerve is the chorda tympani that provides the taste sensation of the anterior two-thirds of the tongue. This little nerve also supplies parasympathetic fibers and control of salivary gland function.[6]

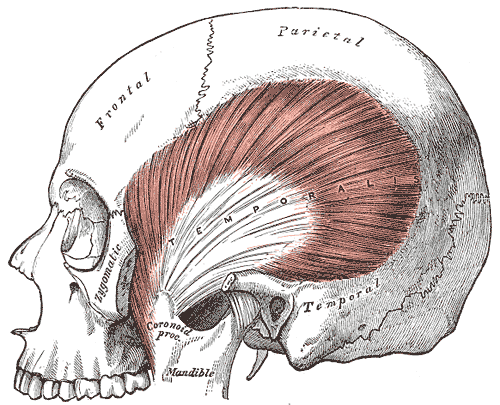

Muscles

The temporalis muscle is one of 2 main closures of the jaw, the other the masseter muscle. These muscles form the crushing action of the jaw, while the weaker openers of the jaw are the medial and lateral pterygoid muscles. As a practical demonstration, you can take your hand and hold a dog’s jaw closed, since the weaker openers are much less effective than the crushing muscles.

Surgical Considerations

Fractures of the temporal bone used to be categorized by the direction of the fracture regarding the pyramid, or transverse to the long axis of the pyramid and longitudinal or along the long axis of the pyramid. Since many fractures are not that simple, a newer classification has emerged. The later categorizes fractures as involving the otic capsule, or not (otic capsule sparing). The former often results in a severe hearing loss. Surgical decompression of the facial nerve is possible, and identification of the fracture course is thus crucial.[7][8]

Benign tumors of the internal auditory canal have previously been called acoustic neuromas. However, this type of tumor, which involves the acoustic division of cranial nerve VIII, is rare, and the correct term is vestibular schwannoma, a benign tumor involving the sheath around the nerve, and usually involves the superior vestibular division of cranial nerve VIII. The latter can sometimes be removed from the nerve, while the former involves sacrificing the nerve.[9]

Infections of the temporal bone are often transitory and mild, such an involvement of the middle ear cavity, or otitis media. However, infections of the mastoid air cells can break through into superficial extra-temporal bone tissues, forming an abscess, or a Bezold’s abscess named after Friedrich Bezold, a German otologist, who first described this condition in the 1800s. The latter can expand, and in rare cases, cause thrombosis of the internal jugular vein. Abscesses can also extend into the petrous apex, and breakthrough into the intracranial structures, causing a perforated eardrum or draining ear, severe pain, and cranial nerve dysfunction, usually cranial nerve six (abduction of the eyeball). This type of infection is called petrous apicitis or Gradenigo syndrome, named after an Italian otologist of the early 1900s.[10]

Traumatic injuries can cause significant blood loss due to a scalp laceration. Traumatic or congenital connections between the STA and temporal veins can cause an arteriovenous malformation, which can be cured either through surgical ligation, or transcatheter embolization therapy.

Clinical Significance

Giant cell or temporal arteritis is a systemic inflammatory disorder that occurs in older individuals and can result in neurological, ocular, and systemic complications. This vasculitic disorder often involves the temporal, occipital, ophthalmic, and proximal vertebral arteries. It may present with jaw claudication, headache, visual disturbances, and scalp tenderness. The diagnosis must be entertained in an individual over the age of 50 with a headache and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR).

If there is a delay in diagnosis, it can lead to permanent blindness. The clinician can perform a temporal artery biopsy to make the diagnosis, and prompt treatment with steroids is necessary to prevent the visual complications. Steroid-resistant patients can receive therapy with cyclosporine or methotrexate. Recovery is the rule of treatment, and the steroids can be tapered in 4 to 6 weeks. Untreated patients have a very poor prognosis because of progressive loss of vision. Other complications include polyneuropathy and multi-infarct dementia. Plus, long-term steroid use is also associated with many other complications.