Continuing Education Activity

Hepatobiliary scintigraphy is a diagnostic nuclear medicine procedure that uses radiotracers to evaluate the biliary system and indirectly, the liver. The radiotracer used is iminodiacetic acid (IDA) or a variant. This is administered intravenously, bound to albumin, transported to the liver, and excreted into the biliary system. The utility of hepatobiliary IDA (HIDA) scan is that the radiotracer follows the bilirubin metabolic pathway and excretion into the bile ducts and thus is especially helpful in identifying gall bladder pathology. This activity describes the indications for the hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid scan and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the management of patients with suspected gall bladder disease.

Objectives:

- Describe how gallstones form.

- Explain how a hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid scan is performed.

- Explain what the hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid scan might reveal.

- Employ interprofessional team strategies for enhancing care coordination and communication to advance the evaluation and management of gall bladder disease and improve patient outcomes.

Introduction

Hepatobiliary scintigraphy is a diagnostic nuclear medicine procedure which uses radiotracers to evaluate the biliary system and also, indirectly, the liver. The radiotracer used is iminodiacetic acid (IDA) or some close variant which is administered intravenously, bound to albumin, transported to the liver, and excreted into the biliary system. The utility of hepatobiliary IDA or HIDA scan is that the radiotracer follows the bilirubin metabolic pathway and excretion into the bile ducts.[1][2]

Thus, in the case of acute cholecystitis which is largely caused by obstruction of the cystic duct, radiotracers cannot enter the gallbladder which is demonstrated by gallbladder non-visualization. The hallmark of chronic cholecystitis is decreased ejection fraction measured objectively with maximum gallbladder radiotracer signal and minimum radiotracer signal after administration of sincalide which contracts the gallbladder. Biliary atresia or distal biliary obstruction is demonstrated by the absence of radiotracer in the duodenum. Extrabiliary radiotracer signifies biliary leak, etc.[3]

Ultrasound has been the primary modality for initially assessing gallbladder pathology. In suspected acute cholecystitis sonographic findings (gallbladder wall thickening, cystic duct dilation, pericholecystic fluid) are secondary and take time to develop. A HIDA scan demonstrates cystic duct obstruction which is the underlying primary event and immediately apparent. Scintigraphy is unlikely to supplant ultrasound as the initial modality for right upper quadrant pain because ultrasound is readily available, is portable, fast, requires minimal patient preparation, avoids ionizing radiation, and may offer alternative diagnoses.

Anatomy and Physiology

The biliary system is made up of intrahepatic and extrahepatic ducts. The liver secretes bile into small intrahepatic ducts which coalesce to form the left and right hepatic ducts. These ducts unite to form the common hepatic duct, which then merges with the gallbladder cystic duct to form the common bile duct. The common bile duct courses to join the pancreatic duct which enters the second portion of the duodenum through the ampulla of Vater, or hepato-biliary ampulla. The circular muscle surrounding the ampulla of Vater is the sphincter of Oddi which opens and closes the ampulla.

Indications

Hepatobiliary scintigraphy evaluates the function of hepatocyte secretion, patency, and integrity of the biliary ducts, dynamic gallbladder bile clearance, and sphincter of Oddi functionality. The following conditions can be evaluated using a HIDA scan:

- Acute cholecystitis

- Chronic cholecystitis

- Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction

- Biliary atresia

- Biliary leak

- Biliary stent patency

Acute cholecystitis is among the most common clinical indications for HIDA scans. Acute calculous cholecystitis results from gallstone biliary obstruction and causes more than 90 percent of all acute cholecystitis cases. The remaining 10 percent of these cases are due to biliary stasis leading to acute acalculous cholecystitis which affects the very old, the very young, the critically ill (trauma, burn, and immunocompromised patients), and patients on total parenteral nutrition.[3]

Biliary atresia is a rare but serious cause of neonatal jaundice which can cause irreversible liver damage if not surgically shunted within the first 2 to 3 months of life. This surgery is a stop-gap measure allowing the infant to grow and ultimately receive liver transplantation. Excretion of the radiotracer into the duodenum at 24 hours effectively rules out biliary atresia. However, the absence of excretion does not confirm the diagnosis of biliary atresia since biliary edema from neonatal hepatitis causes a similar presentation.[4]

A biliary leak is diagnosable by visualization of radiotracer outside the biliary pathway following surgery, trauma, or liver transplantation.

HIDA can evaluate a functional biliary stent by the identification of radiotracer signal within the duodenum.

Contraindications

Absolute contraindications such as anaphylaxis to the radiotracer are very few and rare.

Relative contraindications mainly concern patient preparation. Various drugs may modulate the biliary system.

Opiates must be withheld for at least 6 hours before scanning because they cause a functional obstruction at the sphincter of Oddi which can be indistinguishable from a true obstruction. Severe pain requiring control with frequent opiate administration is suboptimal and may prevent evaluation with hepatobiliary scintigraphy. Increased intracranial pressure in children is an absolute contraindication to morphine administration, as is respiratory depression in a nonventilated patient. If a patient has a history of anaphylaxis to morphine and the HIDA was ordered to evaluate for acute cholecystitis, delaying imaging at 4 hours is the recommendation.

Other medications associated with poor gallbladder contractility require an evaluation of the benefit of diagnostic evaluation with scintigraphy versus the risk of medication modification or cessation. These medications include[4]:

- Atropine

- Benzodiazepines

- Ethanol

- Indomethacin

- Nicotine

- Nifedipine

- Oral contraceptives

- Octreotide

- Theophylline

Conditions that decrease gallbladder contractility include[4]:

- Achalasia

- Celiac disease

- Crohn's

- Diabetes mellitus

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- Pancreatic insufficiency

- Pregnancy

- Sickle-cell disease

Equipment

The procedure requires a large field-of-view gamma camera together with a low-energy all-purpose collimator.

Personnel

According to the Society of Nuclear Medicine SNM Procedure Guideline for General Imaging V6.0, there are three necessary personnel types to calibrate equipment, administer radiopharmaceuticals, and interpret a nuclear study. They recommend a board-certified physician in either nuclear medicine or nuclear radiology, a medical physicist certified in “the appropriate subfield by the American Board of Science in Nuclear Medicine or by the American Board of Radiology,” and a nuclear technologist certified “in Nuclear Medicine by the Nuclear Medicine Technology Certification Board...”

Preparation

Preparation depends on the clinical question under consideration. Preparation for evaluation for cholecystitis is different than preparation for biliary atresia.

For evaluation of cholecystitis patients are instructed to fast 3 to 4 hours before IDA injection. Fat stimulates the secretion of cholecystokinin which causes gallbladder contraction and artificially absent gallbladder on the scan. Fasting 3 to 4 hours prior to injection of the radiotracer allows the passage of ingested contents and relaxation of the gallbladder.[4]

On the other hand, fasting for more than 24 hours allows gallbladder time to resorb water from bile (a normal physiological process) which thickens and prevents radiotracer entry; this may lead to a false positive study non-visualization of the gallbladder). In the fasting population a cholecystokinin analog, sincalide, should be given prior to the study to contract and empty the gallbladder. Intravenous administration of sincalide is 0.02 micrograms/kilogram administered over one hour. Tc-99-HIDA should be injected at least 30 minutes after sincalide administration to allow adequate gallbladder relaxation.[4]

For evaluation of biliary atresia phenobarbital-enhanced cholescintigraphy is used to differentiate neonatal jaundice and biliary atresia. Phenobarbital is a medication which induces hepatic enzymatic activity, bilirubin conjugation, and excretion. The recommended dose is 5 mg/kg/day for five days prior to the scan.[4]

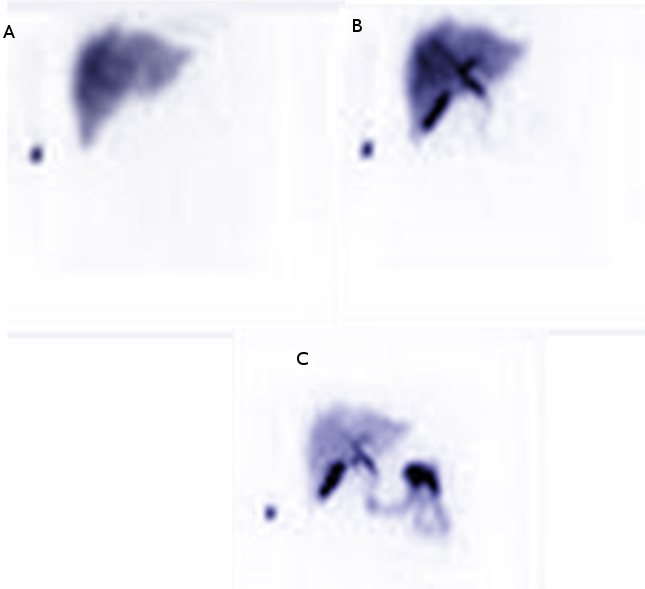

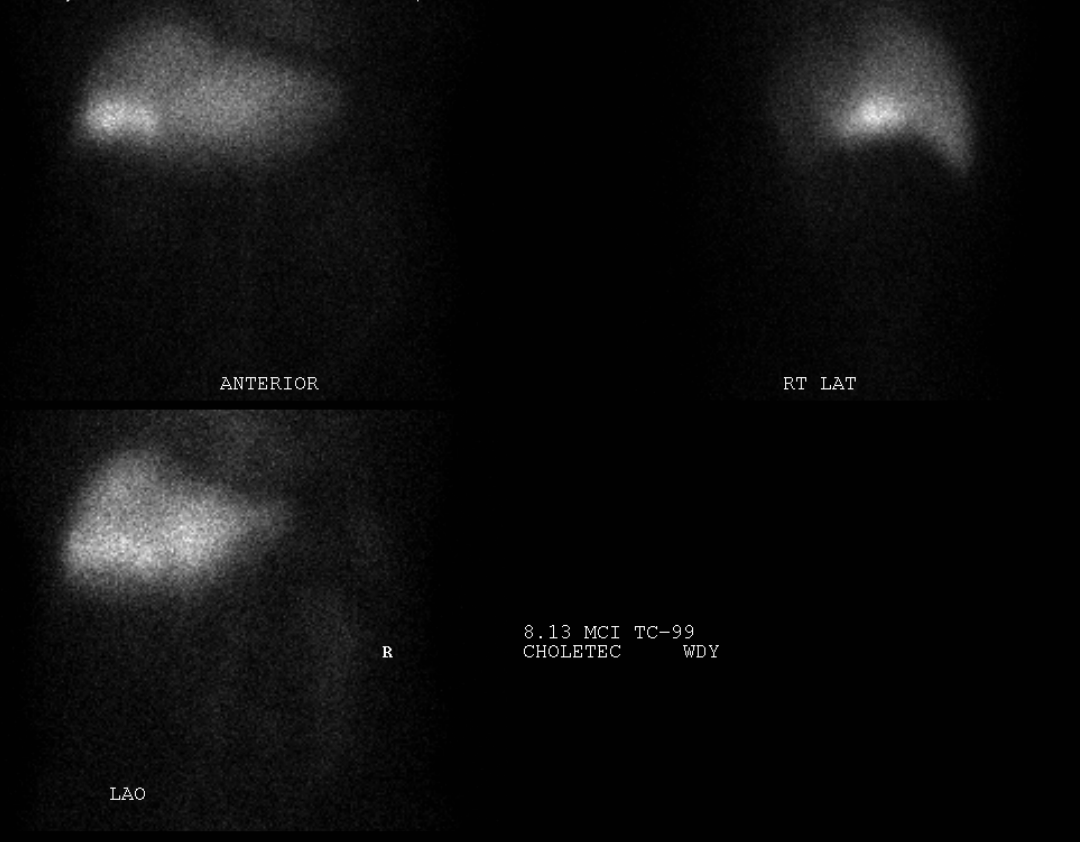

Technique or Treatment

The first hour of the exam is fairly standard regardless of the indication. The patient lies supine on a table. Tc-99 is rapidly infused, and a computer starts collecting images. For the first minute, 60 one-second frames are acquired, followed by 60 one-minute frames. At one hour, left anterior oblique and right lateral views are obtained to differentiate signal from the common bile duct, gallbladder, and duodenum. The left anterior oblique view shifts the gallbladder anteriorly and the common bile duct and duodenum posteriorly.

After the first hour of the exam, the various techniques used may change depending on the clinical question or suspected diagnosis. Some conditions (biliary leak, stent patency, biliary atresia, evaluation for hepatocellular carcinoma) require direct visualization of signal outside the biliary system, biliary anatomy, focal areas of decreased uptake, and/or passage of signal into the duodenum. Other conditions such as acute cholecystitis, chronic cholecystitis, and biliary obstruction evaluate for biliary duct patency.

Acute Cholecystitis

The absence of gallbladder signal at one hour is unusual but not sensitive or specific enough to diagnose or exclude acute cholecystitis. At one hour, there are two options which increase sensitivity and specificity. The first is acquiring delayed imaging at 3 to 4 hours. However, delayed images are suboptimal in the setting of acute cholecystitis when prompt diagnosis and intervention are preferred. Current practice for gallbladder non-visualization at one hour employs the second option which is the administration of a sub-analgesic dose of morphine which causes the sphincter of Oddi to contract and the ampulla of Vater to close. This diverts incoming bile to the gallbladder. In a normal patient filling of the gallbladder will be visible at 5 to 10 minutes after morphine administration and be complete by 30 minutes. The entire exam can be completed in 90 minutes. Continued non-visualization of the gallbladder confirms the diagnosis of acute cholecystitis. Morphine administration in cholescintigraphy is approximately as sensitive as delayed imaging.[4]

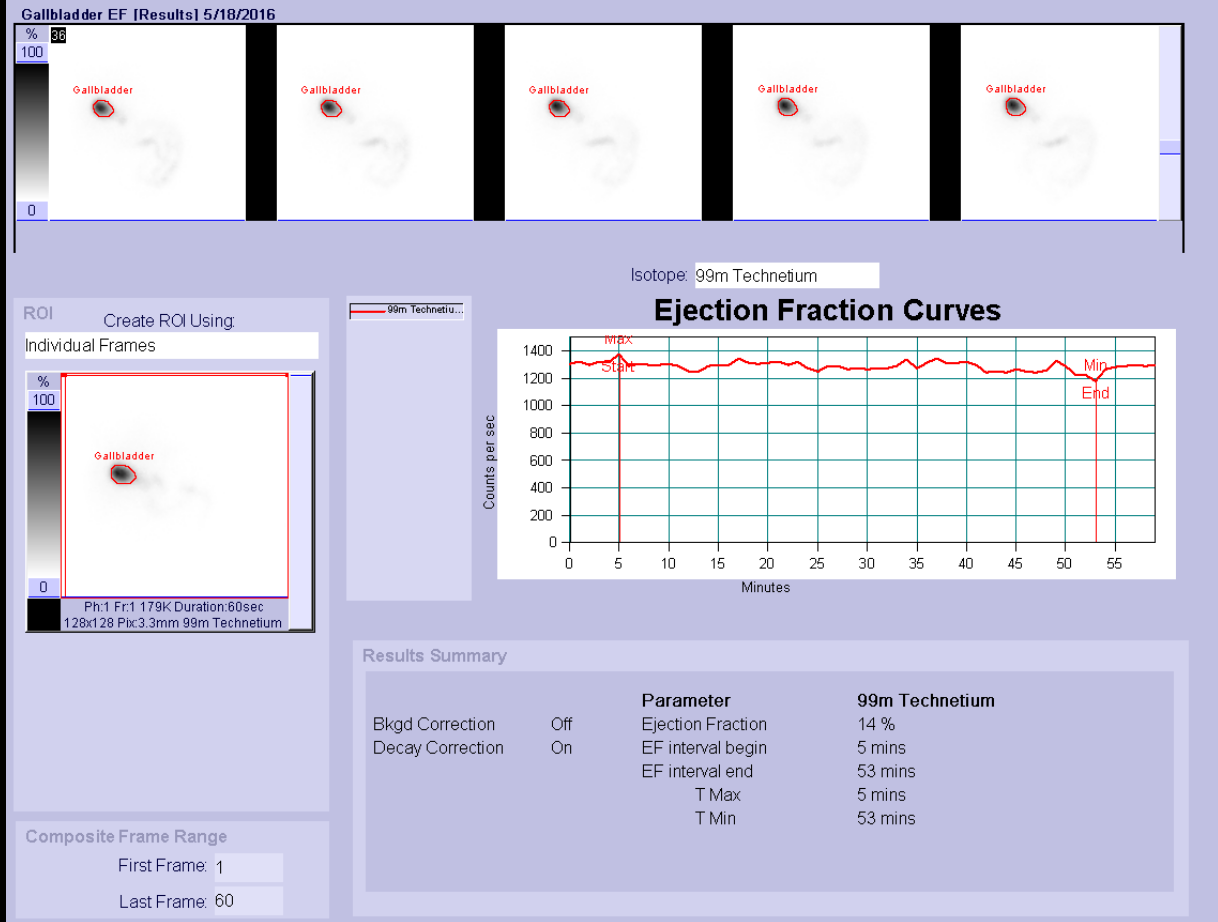

Chronic cholecystitis

The hallmark of chronic cholecystitis is gallbladder inflammation from decreased ejection fraction. Sincalide is administered as a ten-minute infusion (to reduce nausea), and image acquisition occurs in one-minute frames for 60 minutes.[5] Ejection fraction is calculated as a ratio of the difference of maximum and minimum signal to the maximum signal all corrected for background signal. An absolute ejection fraction cutoff in which surgery is or is not recommended is not definitely established but historically is around 40 percent.[6]

Because hepatic cholescintigraphy is a reflection of hepatic physiology, hepatic hypofunction may require delayed imaging even past the usual 3- to 4-hour protocol. In patients with advanced liver dysfunction, it is not unusual to acquire images at 24 hours for gallbladder visualization. Imaging beyond that point is not recommended due to degradation of the radiotracer.

Complications

During a typical HIDA scan, the patient exposure will be 3-4 mSv of radiation which is roughly the amount of background radiation experienced in one year. For reference, a chest x-ray exposes the patient to 0.001 mSv of radiation while a computed tomography of the head requires 1-5 mSv.[7]

Clinical Significance

The utility of hepatobiliary IDA or HIDA scan is that the radiotracer follows the bilirubin metabolic pathway and excretion into the bile ducts; this allows the evaluation of biliary pathology such as obstruction and to a lesser extent evaluation of biliary anatomy and hepatic function.[5]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Ordering a HIDA requires the nuclear radiologist to review the patient's previous imaging modalities, surgical history, current medications, laboratory data, and suspected diagnosis. The imaging team must coordinate with the patient and the patient's provider to ensure that a sufficient period has passed since the most recent meal. Additionally, coordination of risk assessment and possible medication cessation must occur between the nurse practitioner, internist, and primary care provider to optimize the HIDA scan interpretation. [Level V]