[1]

Scalvenzi M, Villani A, Mazzella C, Fabbrocini G, Costa C. Cutaneous Bowen's Disease: an Analysis of 182 Cases according To Age, Sex, and Anatomical Site from an Italian Center. Open access Macedonian journal of medical sciences. 2019 Feb 28:7(4):696-697. doi: 10.3889/oamjms.2019.123. Epub 2019 Feb 20

[PubMed PMID: 30894936]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[2]

Fernández-Sánchez M, Charli-Joseph Y, Domínguez-Cherit J, Guzman-Herrera S, Reyes-Terán G. Acral and Multicentric Pigmented Bowen's Disease in HIV-Positive Patients: Report on Two Unusual Cases. Indian journal of dermatology. 2018 Nov-Dec:63(6):506-508. doi: 10.4103/ijd.IJD_47_17. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 30504981]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[3]

Wozniak-Rito AM, Rudnicka L. Bowen's Disease in Dermoscopy. Acta dermatovenerologica Croatica : ADC. 2018 Jun:26(2):157-161

[PubMed PMID: 29989873]

[4]

Jiyad Z, O'Rourke P, Soyer HP, Green AC. Clinical comparison of actinic changes preceding squamous cell carcinoma vs. intraepidermal carcinoma in renal transplant recipients. Clinical and experimental dermatology. 2017 Dec:42(8):895-897. doi: 10.1111/ced.13211. Epub 2017 Sep 19

[PubMed PMID: 28925042]

[5]

Fernandez Figueras MT. From actinic keratosis to squamous cell carcinoma: pathophysiology revisited. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2017 Mar:31 Suppl 2():5-7. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14151. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 28263020]

[6]

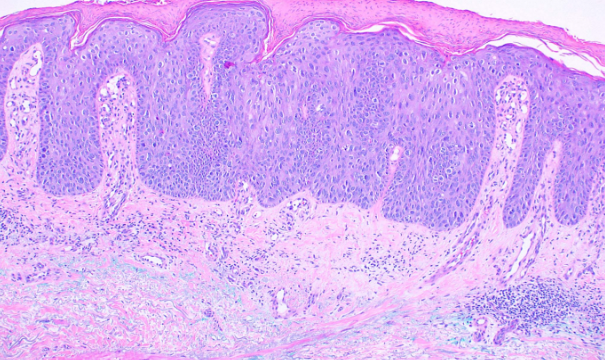

Elbendary A, Xue R, Valdebran M, Torres KMT, Parikh K, Elattar I, Kwon EJ, Elston DM. Diagnostic Criteria in Intraepithelial Pagetoid Neoplasms: A Histopathologic Study and Evaluation of Select Features in Paget Disease, Bowen Disease, and Melanoma In Situ. The American Journal of dermatopathology. 2017 Jun:39(6):419-427. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000000704. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 28525420]

[7]

Majores M, Bierhoff E. [Actinic keratosis, Bowen's disease, keratoacanthoma and squamous cell carcinoma of the skin]. Der Pathologe. 2015 Feb:36(1):16-29. doi: 10.1007/s00292-014-2063-3. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 25663185]

[8]

Zalaudek I, Argenziano G. Dermoscopy of actinic keratosis, intraepidermal carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Current problems in dermatology. 2015:46():70-6. doi: 10.1159/000366539. Epub 2014 Dec 18

[PubMed PMID: 25561209]

[9]

Lazarevic D, Ramelyte E, Dummer R, Imhof L. Radiotherapy in Periocular Cutaneous Malignancies: A Retrospective Study. Dermatology (Basel, Switzerland). 2019:235(3):234-239. doi: 10.1159/000496539. Epub 2019 Apr 2

[PubMed PMID: 30939473]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[10]

Shimizu A, Kuriyama Y, Hasegawa M, Tamura A, Ishikawa O. Nail squamous cell carcinoma: A hidden high-risk human papillomavirus reservoir for sexually transmitted infections. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2019 Dec:81(6):1358-1370. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.03.070. Epub 2019 Mar 29

[PubMed PMID: 30930083]

[11]

Thorsness SL, Freites-Martinez A, Marchetti MA, Navarrete-Dechent C, Lacouture ME, Tonorezos ES. Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer in Childhood and Young Adult Cancer Survivors Previously Treated With Radiotherapy. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network : JNCCN. 2019 Mar 1:17(3):237-243. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2018.7096. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 30865918]

[12]

Zink A. [Non-melanoma skin cancer : Pathogenesis, prevalence and prevention]. Der Hautarzt; Zeitschrift fur Dermatologie, Venerologie, und verwandte Gebiete. 2017 Nov:68(11):919-928. doi: 10.1007/s00105-017-4058-5. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 29018888]