Introduction

The central nervous system (CNS) is a complex network of components that allow an organism to interact with its environment. It is made up of multiple different parts, each of which plays a different role. Primarily, the CNS is formed by the upper motor neurons (UMN) which carry signals for movement down to the lower motor neurons (LMN) which signal the muscles to either contract or relax.

The UMN further subdivides into multiple tracts, each of which has specific functions within the body. Specifically, the pyramidal tract is the main pathway that carries signals for voluntary movement. Lesions to the pyramidal tract can lead to devastating consequences such as spasticity, hyperactive reflexes, weakness, and a Babinski sign (stroking the sole of the foot causes the big toe to move upward). These symptoms are all characteristic of an upper motor neuron lesion. However, certain symptoms are specific to a pyramidal tract lesion.[1]

Structure and Function

The pyramidal tracts are part of the UMN system and are a system of efferent nerve fibers that carry signals from the cerebral cortex to either the brainstem or the spinal cord. It divides into two tracts: the corticospinal tract and the corticobulbar tract.

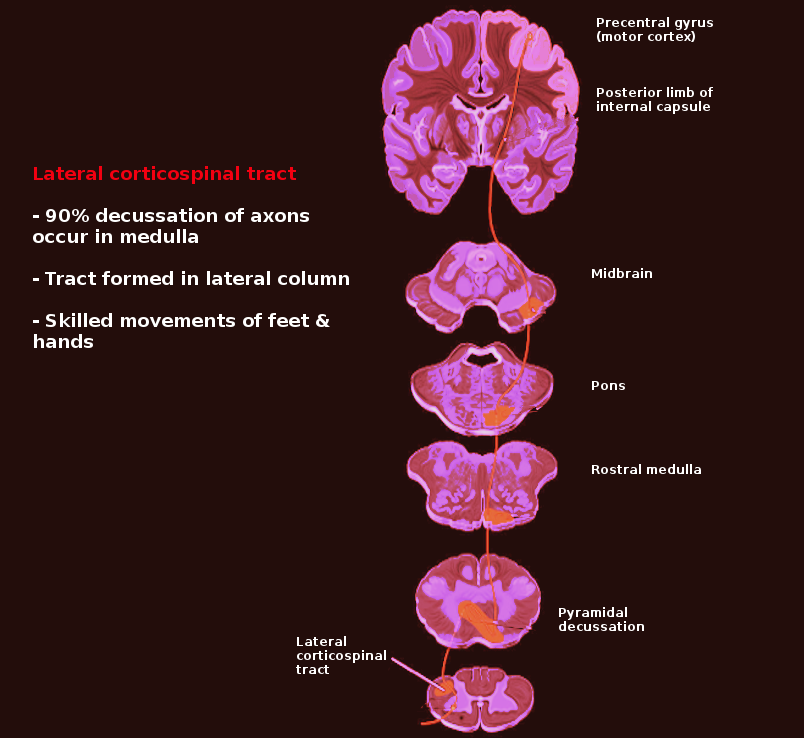

The corticospinal tract consists of neurons that synapse on the spinal cord controlling movements in the limbs and trunk. It originates in multiple areas of the brain, mainly in the primary motor cortex (Brodmann area 4) and in premotor areas (Brodmann area 6). However, it can also originate from the somatosensory cortex, cingulate gyrus, and the parietal lobe. From here, it will descend through the corona radiata, internal capsule, cerebral peduncles, pons, and upper medulla. Once it reaches the lower medulla, about 85 to 90% of the fibers will cross over or “decussate” at the pyramidal decussation to form the lateral corticospinal tract (LCST). They continue their descent in the lateral funiculus and terminate at all levels of the spinal cord. A few of these fibers that are responsible for fine motor function such as controlling finger and hand movement will synapse directly on lower motor neurons. However, most will terminate in lower motor neuron “pools” (groups of interneurons that process and integrate the information before passing it on to the lower motor neurons). At the pyramidal decussation, the 10 to 15% of fibers that did not decussate will continue down uncrossed as the anterior corticospinal tract (ACST). These fibers are involved in controlling proximal muscles such as those in the trunk. Typically lesions of the ACST tend to have a minimal clinical effect.

The pyramidal decussation is a critical concept to understand. Because of the crossing over of the fibers, the location of the lesion will determine which side the symptoms will arise. Lesions above the decussation will cause symptoms on the contralateral side of the body, whereas lesions below the decussation (typically the spinal cord) will cause symptoms on the ipsilateral side.

The corticobulbar tract synapses on the cranial nerves controlling muscles of the face, head, and neck. It originates in the frontal lobe’s primary motor cortex and follows a similar path to the corticospinal tract. It descends through the corona radiata and the internal capsule. They will then exit and synapse directly on the lower motor neurons of cranial nerves. The fibers of the corticobulbar tract bilaterally innervate almost every cranial nerve except for cranial nerves VII and XII, which are innervated by the contralateral cortex. What this means is that a corticobulbar tract lesion on the left side of the face will cause weakness of the right side. However, since every other cranial nerve except for VII and XII are innervated bilaterally (both the left and right hemispheres), lesions to both sides of the corticobulbar tract will need to occur for symptoms to appear.[2][3]

Embryology

The pyramidal tract arises from layer-V pyramidal cells in the cerebral cortex. In humans, the pyramidal tract is one of the last developing descending pathways. While the fibers of the pyramidal tract reach the pyramidal decussation by the eighth week of fertilization, the actual development takes much longer, and full myelination does not fully complete until between 2 and 3 years of age. A multitude of genes guides this developmental process. However, much of this process is still being researched and is not fully known.[4]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The pyramidal tract, specifically the corticospinal tract, spans an incredibly long distance along the body. Damage to specific vasculature structures can lead to damage to the tract.

The pyramidal tract originates in the primary motor cortex. The primary motor cortex for the face and upper extremities receive blood from the middle cerebral artery (MCA) while the primary motor cortex for the lower extremities receives blood from the anterior cerebral artery (ACA). An occlusion of either of these arteries can lead to weakness in the associated extremities. As the corticospinal tract passes down, it will go through the corona radiata and internal capsule, which are innervated by the lenticulostriate arteries (branches of the MCA). The occlusion of these arteries will lead to the contralateral weakness of both upper and lower extremities. As the corticospinal tract passes down into the brainstem, it gets supplied by the basilar artery. The blockage of blood here can result in a variety of symptoms ranging from isolated nerve palsies to tetraplegia or death.[5]

Surgical Considerations

Pyramidal tract lesions can have devastating consequences if not discovered quickly. The most important aspect of surgery focuses on determining the location and cause of the lesion, which will help dictate the procedure. A detailed history and physical exam will aid in guiding this process. Pyramidal tract lesions will present very similarly to upper motor lesions with symptoms such as hyperreflexia, weakness, spasticity, and a Babinski sign. Damage to the corticobulbar tract can present with additional symptoms of lower facial weakness and changes to speech.

Initial treatment for these lesions is typically intensive rehabilitation and exercise. They can also be managed with medical interventions such as botulinum toxin, benzodiazepines, and baclofen, which can all help to decrease the spasticity and contractures to improve functionality and quality of life in patients. It is only when these measures fail, and in the cases of a severe and life-threatening emergency, that surgery becomes a consideration.[6]

Clinical Significance

Pyramidal tract lesions can occur from any type of damage to the brain or spinal cord. They can result from a variety of injuries and diseases such as strokes, abscesses, tumors, hemorrhage, meningitis, multiple sclerosis, or trauma. Damage to the corticospinal tract will present similarly to upper motor lesion syndrome and will present with symptoms such as spasticity, clonus, hyperreflexia, and Babinski sign. Damage to the corticobulbar tract can present with pseudobulbar palsy or damage to cranial nerves VII or X.

Pseudo-bulbar Palsy

The corticobulbar tract bilaterally innervates most of the cranial nerves, except VII and XII, which means that for symptoms to arise from damage to these nerves, both sides of the corticobulbar tract must be injured as is the case in pseudo-bulbar palsy. Symptoms in this condition may include slow speech, dysphagia (difficulty swallowing), dysarthria (difficulty speaking), spastic tongue, and pseudobulbar affect (uncontrollable episodes of laughing or crying).[7][8]

Cranial Nerve VII or X Lesion

Unilateral lesions to either of these nerves will cause contralateral symptoms. Since cranial nerve VII innervates muscles of the lower face, damage to this nerve will cause deviation of angle of mouth towards the opposite side of the lesion due to the overaction of the muscles of the opposite side. Similarly, damage to cranial nerve X will lead to the deviation of the uvula to the opposite side of the lesion.[9]

Other Issues

There are a wide variety of pathologies associated with pyramidal tract lesions. They can be the result of many diseases including stroke, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, multiple sclerosis, and central pontine myelinolysis.

Stroke

Cerebrovascular accidents, or strokes, are caused by occlusion of blood flow to a particular area of the brain. They divide into either an ischemic stroke or hemorrhagic stroke. Ischemic strokes are the sudden interruption of blood supply to a structure due to occlusion or obstruction by a thrombus or embolus. Hemorrhagic strokes result from the rupture of a blood vessel leading to bleeding into the brain. Because the pyramidal tract is such a large structure and receives blood supply from so many different arteries, any occlusion to these supporting arteries can lead to a wide variety of symptoms.[10]

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease that leads to progressive damage of nerve cells within the spinal cord and brain. It causes symptoms of both upper and lower motor neuron syndrome. Upper motor neuron symptoms include spastic gait, dysphagia, dysarthria, and clonus. Lower motor neuron symptoms include muscle atrophy, weakness, and flaccidity. As it progresses upwards, it causes such severe dysphagia and dyspnea that the patient is unable to breathe and generally dies from respiratory failure. It most commonly afflicts adults between the ages of 40 and 70 and at this time is incurable. The only pharmaceutical treatment available that has been shown to extend the lifespan of patients is riluzole, a glutamate blocker.[11]

Multiple Sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis is a demyelinating autoimmune disease of the nervous system. Its manifestations show a wide range of symptoms such as double vision, muscle weakness, coordination trouble, or cognitive disturbance. It is the most common CNS autoimmune disorder, and there currently is no cure. Management centers on improving function after an attack, and preventing recurrent attacks.[12]

Central Pontine Myelinolysis

Central pontine myelinolysis (CPM) is a condition that involves damage to nerve cells in the pons. It can be devastating leading to paralysis, dysphagia, dysarthria, pseudobulbar palsy, and locked-in syndrome (loss of all muscle movement except for eye movements). Its most common cause is the rapid correction of low blood sodium levels (hyponatremia). If the sodium levels are corrected too quickly, water gets driven out of the brain cells which causes widespread damage throughout the entire brain. Once CPM has begun, it cannot be corrected. Therefore, the best treatment of CPM is prevention by correcting hyponatremia at a consistent rate.[13]